And suddenly, there was a flood of white people talking about racial justice...

What will it take for us to stay in this work for a lifetime and to do less harm while we're here?

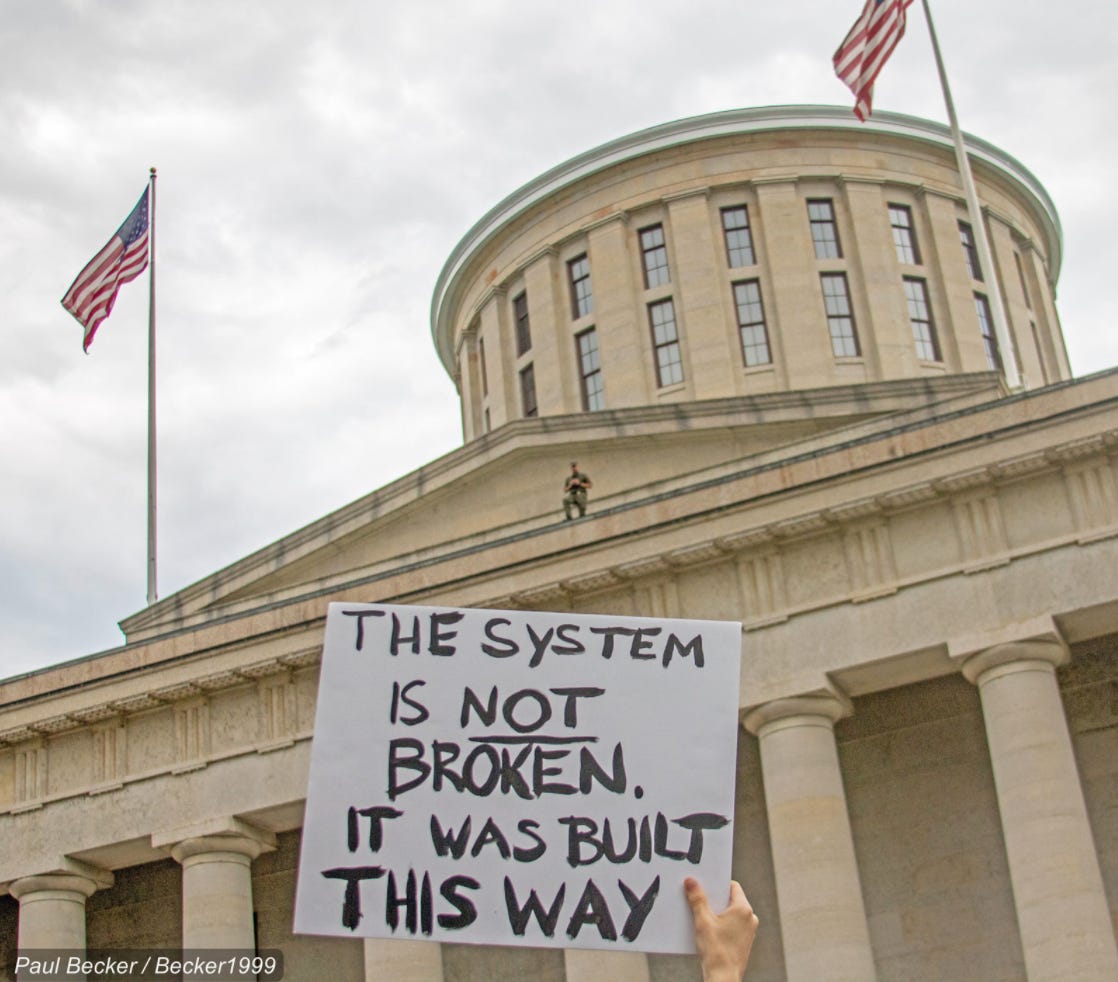

Photo by Paul Backer/Becker1999 (Flickr/Creative Commons)

Notes:

This week’s issue is dedicated to two people. The first, of course, is Breonna Taylor, whose 27th birthday is today. In her honor, I’m following both the financial and action requests listed here. The second is adrienne maree brown, whose book Emergent Strategy has been a source of unspeakable inspiration and challenge these past two weeks. You can support her work by subscribing to her blog or buying her book. Today specifically I’m making a donation to Black Organizing For Liberation and Dignity, an incredible collective I learned about through brown’s work.

Also: There are many more people reading this than a couple weeks ago. Welcome! I haven’t figured out how to make this a more interactive space (should I be actively encouraging comments? probably?) but I’m glad you’re here. If you’re new, this newsletter is an experiment in the idea that while white people should continue to learn from (and compensate) BIPOC thinkers, that there is also value in a complementary conversation with each other.

These are days of hope and rage and confusion and helicopters overhead. These are days of children being maced and elders being shoved to the ground, concussed, bleeding, unresponsive. These are the days of Bibles being held up for cameras while tear gas is still fresh in the air and billy clubs are still being re-holstered. These are days that feel new and different to those of us for whom all this was built to prop up but that are not actually not new at all.

We’ll get to all that.

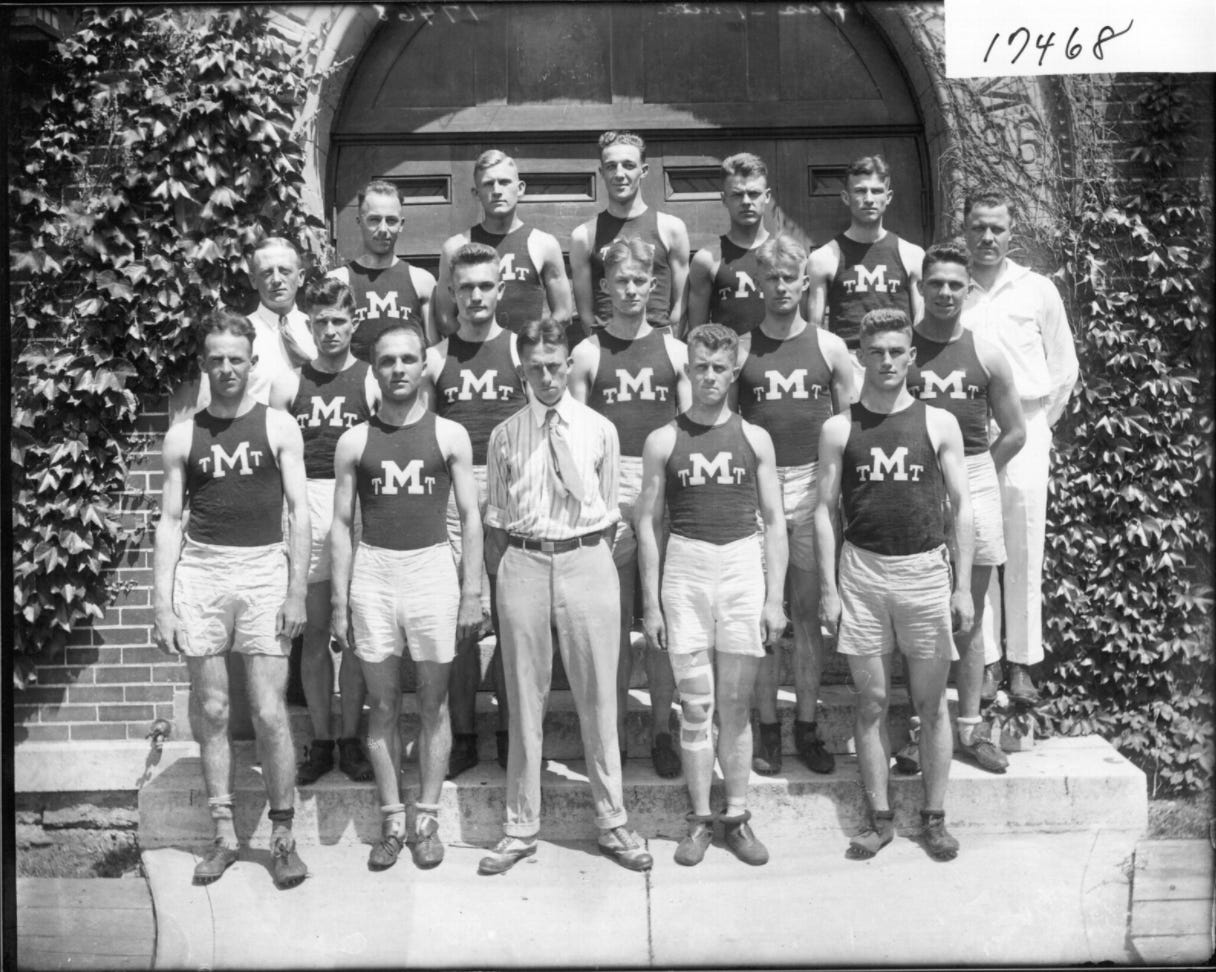

Photo courtesy of Miami University Libraries.

I’m the fifth of six kids in my family. My older brothers had all been runners. A couple of them were pretty successful at it. I didn’t really question whether I was going to be a runner too- it was A Thing Bucks Boys Did (as opposed to Things That Bucks Boys Unequivocally Didn’t Do, like “eat dinner without spilling it on ourselves” or “inspire confidence in prospective prom dates”). I went out for cross country in the fall of Freshman year and it was fun at first— the guys on the team were all nice and there was a spaghetti feed the night before the first race. I remember hanging out in some senior’s basement, listening to Weezer and playing Mario Kart. It ruled.

I got hurt a mile into that first race. Shortly afterwards my family moved back to Montana. The cross country season was over by the time I was settled in and my leg felt better. I went out for spring track, having not trained since my injury and quickly realized… that running was actually really hard. I was slow and my form was awkward and I lost a lot of races. Have you ever lost a long distance track race? It is a uniquely tortuous form of athletic embarrassment. Your mom has to sit up in the stands watching as you run your last lap alone, long after others have finished.

I stayed with track for another season or two, but it was a mess. I was too ashamed of being a Bad Bucks Brother that I didn’t quit, but I remember (a). running to Taco Bell in the middle of practices and downing a couple seven-layers before jogging back and (b). at one point jumping out of the tree in our back yard in hopes that I’d sustain an annoying but not-fully-terrible injury so that I could quit with dignity. These are not the signs of a young man with a healthy relationship to competitive running.

What I’m saying here is that I was really bad at track. Also that sometimes my allegories are really obvious.

Photo by Joe Brusky/Flickr (Creative Commons)

So here we are. There are a ton more white people either newly discovering racial justice work or deepening our commitment to it. Town like Pierre, South Dakota and Great Falls, Montana (places where protests of any sort aren’t regular occurrences), are now filled with “No Justice! No Peace” chants. Friends of yours who a few years ago might have not seen what the big deal was with saying “All Lives Matter” are now full-on police abolitionists. Ice cream companies that very recently were forging relationships with Unilever and Jimmy Fallon are now putting out End White Supremacy statements. And yes, so much is bad right now, just so painfully bad. But to imagine that, for the first time in our lifetime, a critical mass of white people might finally answer the call to support Black, Brown, Asian and Indigenous liberation movements… well there’s something meaningful there, even if its nascent, even if it’s fragile.

You all, I don’t want us to mess this up. I’m hopeful, but I’m so scared.

I can’t speak to what brings other white people to this work, so let’s use me as an example. Here is a partial list of motivations that, if I’m honest, have undergirded my racial justice activism over the year: Sadness, rage, embarrassment, shame, helplessness, fear, guilt, peer pressure and desire for validation from people of color. I’ve been jolted into action by images of Black men dead on the street, by Black and Brown friends and colleagues telling me personally how much I hurt them, by statistics about the vastness of the problem and harrowing personal stories that undergird its perniciousness. I’ve also, however, been motivated by a selfish concern for my own reputation, by a semi-conscious search for the social capital I assumed could come if I were considered a good white person.

Again, I can’t speak to the motivations of others. But I have a hunch that we wouldn’t be coalescing in this particular moment— where George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery and Tony Mcdade had to die before we all stopped and took notice— if I wasn’t the only white person whose pathway to this work wasn’t muddled and confused.

I’m going to save my thoughts on our more selfish motivations for a different piece so as to give it the full space it deserves . I’ll simply say, if you honestly feel you don’t have them, bless your pure and beautiful heart. I for one struggle to move beyond mine every single day. I learn so much, most of it quite painful and embarrassing, from an honest daily accounting of “so why did I REALLY say/write/do/not do ________?”

Let’s say, though, that at least some of your collective white motivations right now are empathetic. You are legitimately grieving for others — perhaps for Black people in general, perhaps for specific Black people in your life, perhaps Black people who are intensely close to you (children, partners, etc.). You are truly enraged because people you love have recently been on the receiving end of a police baton. You are earnestly regretful, as you play back a whole parade of your own crimes of omission and commission at work, at home, at school.

I’m not here to shame any of those reactionary but empathetic emotions. They are real. They are honest. They are powerful tools in building a better world. They are the currency of protest and disruption and stopping business as usual. But for those of us who, very soon, will be given the choice to turn our heads back again and return to our lives, these motivations alone will not sustain you, nor will they prevent you from causing harm in the meantime.

In the short term, if we, as white people, are only motivated by a desire to do something about our sudden sadness and anger, we will act in frantic ways, seeking the quickest possible cleansing of these uncomfortable feelings. We will be more likely to show up at protests in ways that make things more dangerous for Black organizers. We will be more likely to flood the inboxes of Black activists and writers begging them to tell us what to do for free. We will be more likely to treat individual Black voices not as complex human beings but as walking Rosetta Stones who contain the key to us eliminating all racism from our lives. We will be more likely to stop showing up when it is our behavior called to account rather than that of law enforcement.

It is in the long term, though, that the larger casualties of singular motivations will come to bear. We will, of course, be more likely to burn out and leave as soon as we don’t feel as acutely sad any more. More importantly though we will also be less radically imaginative… and less open to the imagination of the young Black Brown and Indigenous activists leading us towards a more liberatory world.

Photo by Chuck Patch/Flickr (Creative Commons)

What I’m talking about here is moving beyond guilt and shame towards the kind of motivations that make you get out of bed every day and say “I legitimately can’t wait to help build a better world— even if its hard, even if I get no credit for being part of the work, even if it will take mine and many other people’s lifetimes.”

I’m talking about the dreams we give ourselves permission to dream. I’m talking about questions like these.

What would a world look like in which the intellect, brilliance, creativity and beautiful weirdness and individuality of every Black Brown and Indigenous person were allowed to flourish?

What would we all learn about how to live together in community if our goal was the well-being of everybody rather than the comfort of a few of us?

How much safer would we all be if our aspiration was actually to take care of our collective needs and not to protect the current world of whiteness and wealth by any (violent, immoral, dehumanizing means necessary?

What beautiful and radical policy and governmental ideas that we, in America, currently believe to be impossible would suddenly be possible if millions of white people were willing to vote for something beyond the protection of their piece of the pie?

How much would our children learn and discover together if our education system (and the corresponding municipal boundaries that reinforce it) was no longer balkanized to protect advantage and pre-existing hierarchy? What could be true if every white parent of a soon-to-be-kindergartner believed that their kid will only truly be ok if every kid is allowed to be ok as well?

How truly impactful could you and your colleagues be if the goal of your business/nonprofit/governmental agency/educational institution was actually to leave this world better rather than (insert one: “maximize shareholder value,” “keep donors happy,” “make sure that we all take home a nice paycheck and get promoted at the rate we expect to”)?

How healthy could we all be if the only way we answered questions such as “should we build that?” “do we need _____?” “does that person deserve care?” and “is this the best way to do ________?” was with an eye towards whether it would keep everybody alive and flourishing?

What could be true in your relationships with friends, colleagues and neighbors if your goal was to truly love and be present for them rather than to focus on what they thought of you, whether they were a threat to your goals and what they could or couldn’t do for you transactionally?

When all is said and done, the world is neither a better nor worse place because my high school track career was rooted in such shallow motivations. But for those of us with the ability to choose when we look and when we turn away, when we engage in liberatory work and when we engage in the work of self-preservation, the shallowness or depth of our motivations has life or death consequences.

It is good that there are more white people talking about justice these days. I want us all in this fight. Not leading, of course, but working with passion and imagination and rage and sadness and hope. I want us to stay in it for our lifetimes. I want us to do so in a way that makes it easier for everybody to do this work and, most importantly, for Black, Brown and Indigenous people to lead it.

I am legitimately thrilled and grateful to be here with you. Now let’s start walking towards someplace better.

Song credits: Funkadelic: Good Thoughts, Bad Thoughts, Belle and Sebastian “The Stars of Track and Field”