TOP NOTES:

Hi, all. I’m back from vacation with my family. I was out for a bit more than a week (the extended timeline may or may not have been enabled by the fact that we misread the Milwaukee Public Schools calendar and incorrectly thought that our kids had this Monday off; we are exceptional parents). It was both quite lovely and tiring (in a hyper-specific “we drove across a good stretch of Ontario and Quebec through a freak late-spring ice storm” way). If you ask my six-year-old what she loved most, she will tell you about the hotel breakfast where we let her spread Nutella on a chocolate croissant. She’s not wrong.

Thanks, as always, for considering a paid subscription. As you might know, Substack recently launched Notes, which is more like a social media space than anything they’ve made before (a quick aside on that: yes, I’ve been using it personally, maybe it’ll turn out more pleasant and less toxic and Nazi-y than other social media sites, maybe not; if you’re not looking for a social media site, it’s probably not for you and that’s totally OK!). I bring it up merely because my primary experience of that space is that it’s full of people who are sorta like me (“newsletter people,” if you will, all of us trying to cobble together a living from subscriptions) and seeing hundreds of “newsletter people” in there reminded me of how many individual publications are potentially in your inbox reaching out their hands and saying “hey, please chip in.” I bet that’s exhausting! That’s just to say, I don’t take it lightly when any of y’all make that jump for this particular operation. Like so many other newsletter people, I continue to exist in that liminal space between “this whole writing/organizing thing was a fun lark but there’s no way to make it work financially” and “this is actually a sustainable career!!!” and every little bit helps.

Speaking of which, in response to some kind requests from folks who really, really want a Barnraisers tote bag (see below, as modeled by me), I changed the “pledge drive” subscription level. A $100 a year pledge now only gets you all the fun perks of regular membership (the weekly discussion thread, the Flyover Politics discord, the occasional nonsense posts) plus a tote bag or shirt.

The White Pages: Typos? Yeah, probably. But also tote bags!

Today is Ruination Day, my favorite made-up holiday. I write an essay about it every year.

Last year’s edition provided a decent overview of how and why I came to care so much about this holiday (as well as a lot of words about going to two funerals in 48 hours) but here’s the quick summary.

April 14th is a pretty weird day, historically speaking (and by “weird” I mean “a disproportionate amount of tragic events in U.S. history happened on that single date”).

The traditional Ruination Day historical trifecta is the sinking of the Titanic, Black Sunday (the single most devastating day of the Dust Bowl disaster), and Lincoln’s assassination.

The term “Ruination Day” was coined by the singer-songwriter Gillian Welch, who wrote two different songs about April 14th for Time, The Revelator (a miraculous gem of an album).

I’m not usually one for celebrations of the macabre and tragic, so it’s a bit odd that I’m so into the whole Ruination Day idea. My best explanation is that there’s just something about the concept of a sin-eating day where we can imagine that all of the world’s pain resides. It’s not that I believe it’s true— there’s plenty of evidence that the remaining 364 days of the year have not been cleansed of tragedy thanks to April 14th’s noble sacrifice. It’s just that I understand so deeply why we would want it to be true, and even if it isn’t, I appreciate the chance it provides to collectively memento mori the world’s brokenness for 24 hours.

Now that you’re caught up, let’s talk about villains. The thing is, there is a real outlier in those three April 14th tragedies. Neither the Dust Bowl nor the Titanic were caused by clear, singular perpetrators. They were both crimes of capitalism and colonization and imperialism and hubris. Yes, individual mistakes were made (somebody had to steer into that iceberg) but all within a broader collective cultural logic.

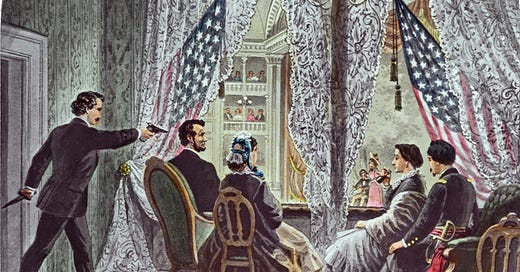

There was nothing vague and mysterious about Lincoln’s assassination, though.

There was a single guy with a gun.

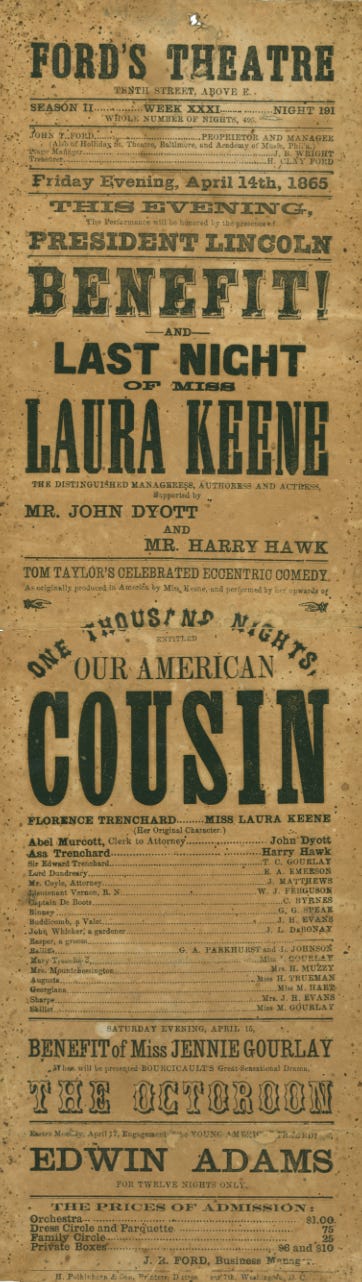

He did it in public, in front of hundreds of witnesses. Since he was a famous actor (a verifiable heart throb!), there was no question as to his identity. Since he was an open Confederate sympathizer who had planned the assassination as part of a larger terrorist conspiracy, there wasn’t any mystery as to his motives. One minute, the United States had a President who had freed the slaves and won the Civil War. The next minute, that President was dead and his assailant was yelling something about tyranny and running out of Ford’s Theater.

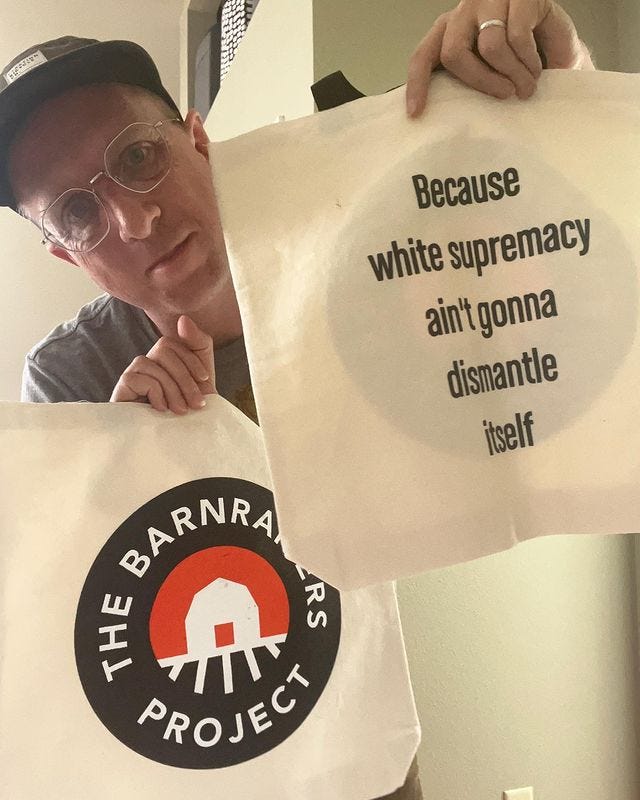

Did you hear what Lincoln was doing when John Wilkes Booth shot him? He was laughing. Laughing! Booth planned it that way; he knew the play Lincoln was watching by heart. He was waiting for Harry Hawk to say the line "Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal; you sockdologizing old man-trap!"and for the President of the United States to subsequently be so consumed by guffaws that he wouldn’t notice footsteps behind him.

That “sockdologizing” line might not sound like a gut-buster (honestly, what a mess!), but you’ve got to understand the context. The play Lincoln was watching, Our American Cousin, follows a pretty classic format. There’s a dumb hick, you see, and he’s hanging out with a bunch of stuck-up posh people. They spend most of the play’s run-time looking down at him, but in the end it’s revealed that he’s smarter than they think. It’s a real one-two punch; the audience gets to laugh at a hillbilly, yet still hold onto their moral high ground in comparison to all of those stuck-up elitists. You likely haven’t watched a performance of Our American Cousin, but you have seen and read hundreds of variations on the form. We tell ourselves stories (about how everybody who isn’t us is either dumb or mean) in order to live.

But back to Booth. You have to really hate a person to commit pre-meditated murder. You have to really, really hate a person to deliberately plan to do so when they’re laughing, when they are at their most human, most relatable, most child-like.

The laughter matters to the story. It suggests that John Wilkes Booth really, really hated Abraham Lincoln. Which he did. It was, in fact, the most singular, defining hatred of his life.

John Wilkes Booth looked down on Black people, of course. He was a White supremacist and a rabid Confederate partisan. You can find all sorts of reprehensible Booth quotes about Black Americans. But he didn’t hate Black people like he hated Abraham Lincoln. A few years before that night in Ford’s Theater, he was visiting his brother in New York when the Irish Draft Riots broke out. That evening, the White people that posed the most direct threat to Black New Yorkers weren’t Confederate soldiers, but mobs of poor Irish immigrants, drunk on a contradictory cocktail of authentic class resentment and recently adopted White supremacy. In response, Booth fashioned himself as a protective hero, literally putting his body on the line to protect Black New Yorkers from the mob.

Now, is White supremacist paternalism better or worse than outright hatred? There’s a case to be made either way. But at the very least, the two emotions are distinct.

Do you know who else John Wilkes Booth didn’t hate? Radical abolitionists, even if their worldview was 180 degrees away from his own. He may have personally attended John Brown’s hanging, but Brown was— per Booth— the noble, respectable enemy. He called him “the grandest character of this century!” and a “rugged old hero.” He respected Brown’s fire, his moral consistency, and his willingness to take matters into his own hands rather than hide behind the veneer of statecraft and a largely non-volunteer army. He admired John Brown, which is to say that he loved what admiring John Brown said about him.

By contrast, Booth considered Abraham Lincoln to be not only a dictator, but an idiot. He was a redneck tyrant in the people’s house, attempting to punish true American patriots like the Confederates simply because they would not bend to his whims. Of course he’d laugh so loudly at Our American Cousin that he wouldn’t know what was coming. Of course he’d be that cocky. Of course he’d be that stupid. Whereas Booth was a “rugged hero,” Lincoln was anything but. Considering our sixteenth President, he once wrote, “This man’s appearance, his pedigree, his low coarse jokes and anecdotes, his vulgar similes, his frivolity, are a disgrace to the seat he holds.”

There were probably a lot of reasons why John Wilkes Booth killed Abraham Lincoln— he was hoping to shift the balance of power between a humiliated South and an ascendent North; he was trying to get back at his Union-supporting brother; he was making up for the fact that— per his mother’s wishes— he didn’t fight in the war and got to be a famous actor instead. We all contain multitudes. Most of all, though, he murdered Abraham Lincoln because he hated him, because he needed to hate him, because without Lincoln as an unredeemable villain, the entire house of cards that was John Wilkes Booth’s epistemology would have come crashing down.

There’s a lot I don’t understand about John Wilkes Booth, but Lord knows I get that part.

I understand the mental twists and turns that a White man who was both named for an English anti-monarchy radical (a paragon of freedom!) and whose family owned slaves (a patently anti-freedom life choice!) might make in order to reconcile the chasms between those two poles. I can imagine why he would look at John Brown and so desperately want to imagine him as a fellow traveler who just happened to be on another team— the abolitionist Montague to his soon-to-be-lost-cause Capulet. I understand why and how it was more appealing for Booth to view himself as a freedom fighter than a defender of the rights of wealthy White people to own other human beings. And of course, I understand why all of that would necessitate a villain to obsess over— a singular human machine against which to rage.

What I’m saying is, I get why John Wilkes Booth would need to believe that Lincoln wan’t a technocratic politician with a different ideology, but instead imagine him as a despot, a tyrant, a power-drunk redneck king. Its the kind of moral hoop-jumping we all engage in when we don’t want to let go of our worldview or position in society, but we can’t quite kick the suspicion that our souls might be less pure than we’d like to pretend.

I may not have to justify my support for the Confederacy, but I live in a world created by it— a world where land is acknowledged, but we don’t do anything about it; where racial wealth gaps are seen but treated as almost geologic inevitabilities; where human beings die in the streets for so many reasons and then other human beings literally or metaphorically step over them as we go about our days. I live (and am treated quite well by) a world where, as Tressie McMillan Cottom wrote earlier this week, we are “never as far from the graves we dig for other people as we hope.”

And because I live in that world, and because it is tremendously difficult to fully reconcile my place in that world, thank God for Trump, thank God for Tucker Carlson, thank God for the various Boeberts and Taylor Greenes and Santoses about whom I know far too much given their relatively minor impact on my life. Thank God for a politics focused less on whether we’re tangibly building a better world together than with the quick-hit satisfaction of scrolling to find out whether or not our favorite villains stepped on a rake this week.

Thank God, because without all of those fixations and shiny objects, I might be forced to admit that I don’t actually know how to reconcile my race, my gender or my footprint on a dying planet with the story I would love to tell about myself. I might have to engage in making the world a better place even if doing so never delivers me the absolution I not-so-secretly crave. I might have to admit that I can’t figure this out alone.

There are people who believe that John Wilkes Booth didn’t die in a shoot-out at a Virginia farm, that he somehow escaped capture and changed his name to John St. Helen. They say that he ran until he reached Hood County, Texas, somewhere between Dallas and the Hill Country. They say that he became a bartender in Granbury, but that he could still recite a suspicious quantity of Shakespearian monologues from memory. What’s more, they say that at one point, John St. Helen thought he was dying and confessed his true identity. The next morning, discovering that he was still alive and that he had accidentally revealed his secret, he disappeared from town, never to be seen again.

The bar that purportedly employed John Wilkes Booth is now a bakery/cafe. As of a few years ago, you could still enjoy a tuna sandwich underneath the “John Wilkes Booth Did Not Die!” mural. As far as I can tell, the current owners have painted over it, which is fitting. John Wilkes Booth gets away again.

“John Wilkes Booth Did Not Die!” is a perfect American story, in that it is easily debunked, but that doesn't mean it isn’t 100% true. Somewhere, likely in Texas, John Wilkes Booth is still with us. He successfully slayed his life-consuming adversary— a man who reminded him, merely by existing, of a cognitive dissonance he would never be able to reconcile. He kept the Old South on life support at its lowest moment, such that it could rise again and again and again. He helped ensure that the first Reconstruction, as well as all those that followed, would be merely a temporary blip in the long march of American White Supremacy. He believed in his core that righteousness could be found solely in whom you hate, so he hated his way into immortality.

John Wilkes Booth was almost certainly killed in a Virginia barn, but also, if you look at the world which we’ve inherited and in whose image that world best reflects, John Wilkes Booth lives forever.

I’m not pretending that the villain on which John Wilkes Booth fixated was morally equivalent to the various misanthropic power-hoarders who animate an outsized level of my energy and attention. Abraham Lincoln wasn’t a perfect President, but that doesn’t make him the same as Donald Trump. Some of my political enemies are actual Nazis, and it’s OK to denounce them as such. All I’m suggesting is that there has to be something more to this life than simply identifying the good guys and bad guys in our midst with a greater degree of moral accuracy. If we could schadenfreude our way to a better world, we’d have arrived there by now.

Perhaps I am so fascinated by Ruination Day— this made-up holiday that exists solely in two folk songs and in my own imagination— because it is comforting to blame something celestial and ephemeral for all the world’s sins. It feels like a step forward from merely depositing them onto another human being’s doorstep. And that might be true.

But the thing about a day is that it only lasts 24 hours. Today, I can engage in the kind of magical thinking that allows me to believe that a single date on the calendar can erase our sins, just as John Wilkes Booth once imagined that a bullet could erase all of his. Tomorrow, though, I will wake up and we will still have a broken world to mend. Tomorrow, I will wake up and no matter how evil I imagine my enemies to be, I will still be as imperfect as the rest of you. Tomorrow, we will wake up and the ruination will not have disappeared. But we will have one another. We will always have one another. And who we get to build with will always matter more than who we get to blame.

END NOTES:

This week’s song(s) of the week:

The floor is yours, Gillian Welch. Thank you, as always, for the gift of my favorite made-up holiday.

As always, you can check out the collected song of the week playlist on Apple Music or Spotify.

I love your work, and I enjoyed reading about Ruination Day for the second year in a row as a subscriber of this newsletter. I want to lift this passage at the end of your piece:

"Abraham Lincoln wasn’t a perfect President, but that doesn’t make him the same as Donald Trump. Some of my political enemies are actual Nazis, and it’s OK to denounce them as such. All I’m suggesting is that there has to be something more to this life than simply identifying the good guys and bad guys in our midst with a greater degree of moral accuracy."

I think here would have been an appropriate place to acknowledge that Lincoln happily led the execution of 38 Dakota people in 1862 during the ongoing campaign of genocide against Native Americans. I believe that understanding each of these historical actors' (Wilkes Booth AND Lincoln's) commitments to the twin projects of white supremacy and settler colonialism is crucial in understanding how we ended up here.

Your newsletter has taught me so much about how whiteness is constantly attempting to find foils within our own white communities in order to grace or exempt ourselves. It is with the knowledge that white people who are uplifted as arbiters of justice (such as, but certainly not uniquely, Lincoln) were also involved in settler colonial and white supremacist projects, that we as white folks can move forward with understanding ourselves and our histories.

Goddamn. That was a beauty, thank you.

I just happened to do a deep dive into the lyrics of those two gems last night, on Ruination Eve (and into the wee hours of the holiday itself) and had my soul rended again, twenty-odd years later. I was transported back by the folk songs and African-American traditionals she references, but this adds layers I would never have considered without knowing the details of the Booth story. I’d so love to hear a conversation between you Gillian Welch about these tracks!