Are We Really “In This Together?“

We have never been in this together. Our country was built on the promise of not having to be in this together. But oh goodness if now isn't the time to try something different.

I’ve been running through downtown Milwaukee lately. These days you’re less likely to collide into people in a central business district than you are on a running trail, so it seems like the safer, more responsible choice.

Well at least that’s my best guess as to what’s the responsible choice. We’re a month into this era of Everything Is Epidemiology and we’re still making the rules up as we go. Downtown is pretty empty though, that’s for sure.

You likely aren’t from Milwaukee, so here’s what you need to know about our downtown: It’s a lot like other downtowns. It used to be bustling, it then became significantly less bustling and now its somewhere along the revitalization continuum. It is increasingly filled with both amenities I appreciate quite a bit (a lovely riverwalk, pleasant places to drink coffee and beer, an aggressively shiny NBA arena that I shouldn’t love because it was unnecessarily publicly funded but that I can’t help but love because have you ever seen Giannis run the entire length of a basketball floor in, like, two steps?) as well as those that are a bit try-hard but which I also don’t mind (murals designed to be photographed and hashtagged, “experience-based” restaurants that call sandwiches “handhelds” and offer giant Jenga, a streetcar that I very much hope becomes a useful part of a humanity-serving public transportation system but which in its first iteration primarily serves the purpose of saying “look, we have a streetcar”).

Have you been to your nearest revitalized-but-suddenly-empty downtown lately? It’s eerie, right? I guess this is where I should say that it feels post-apocalyptic but I haven’t actually lived through an apocalypse. I have, however, been to the Streets of Old Milwaukee at our city’s delightful, quirky Public Museum. It’s a time capsule exhibit— a simulacra built so that museum guests can walk through and pretend that they’re in the early 1900s. I’ve been there a bunch, including right at opening time, when it’s empty and you have the run of the place. That’s what our downtown feels like right now. A museum wing at opening. A “Millennial Land” preserved in amber. An abandoned World’s Fair Display. A presentation of what my generation has been offered as The Good Life.

I’m not even sure how or where you purchase a Confederate battle flag emblazoned with an automatic rifle. I didn’t know they existed until a couple days ago, when one of them showed up at the recent Give Me Liberty [And Also Probably Give Me Death] rally in Lansing, Michigan. This means, of course, that I’m also now aware of the existence of Michiganders who, when shopping for actively hostile flags, pass over the Confederate ones that don’t have assault rifles on them because they’re not threatening enough. I at least appreciate the commitment to historical accuracy here (blowhard eggheads might claim that they didn’t have automatic weapons in the Civil War or that the cradle of the Confederacy wasn’t Grand Rapids but listen, I wasn’t around back then, who am I to say?).

Yesterday, Wisconsin’s Governor extended our Stay-At-Home through the end of May. Almost immediately, the floodgates of dissent (or what passes for floodgates of dissent these days, which is to say, online posting) opened up. Ours is not one of the states that our President, ever helpful, has encouraged citizens to LIBERATE! by force, but I’m sure we’ll get there soon.

Here in un-liberated Wisconsin, thousands of folks have already RSVP’d to a Reopen the State rally next Friday, leaving potential attendees with only a week’s notice to make menacing flag purchases. Tens of thousands have already joined an anti-quarantine Facebook group. Being a generally curious and empathetic neighbor, I joined as well.

Here’s what you learn from spending a day or so scrolling the comments of Anti-Shelter-at-Home Facebook groups. People (to be clear, it absolutely appears to be all white people) are angry! And yes, many of the folks making the biggest fuss haven’t just discovered a Don’t Tread On Me vibe in the last few days. But amidst the hornet’s nest of Professional Liberty Defenders and Patriotic Hucksters and Sovereign Citizens are, in fact, a good number of not-all-that-political folks who are scared and hurting and confused.

It’s possible to show sympathy in many directions while also acknowledging that pain and suffering isn’t experienced equitably. And so, while every aspect of the current moment (both medically and economically) is hitting Black, Latinx, Asian and Indigenous communities in our state the hardest, the pain and confusion being expressed by white exurban and rural Wisconsinites is real. Their bars and hair salons really are hemorrhaging money. Their life’s work truly is at risk. It is legitimately hard to understand why their world has been put on pause when counties up north have seen only a handful of cases and their hospitals are empty.

Since joining the group, I’ve done some extremely ineffective outreach to folks whose posts really stuck with me- small business owners who have been hit hard and who sound like they could use a few extra bucks, people who seem to be especially distraught and might appreciate a kind word. There are plenty of reasons why a stranger reaching out on Facebook might not be well-received, so I won’t read much into the relative silence I’ve received in response. As the fury keeps growing though, what does seem clear is that the actual material pain folks are feeling is one thing, but that’s not actually the root of the collective rage and consternation. It is the roar of a community of people mourning the loss of the only real promise their country ever gave them— the promise of being left alone, the promise of not having to be responsible for the common good. Yes, their pocketbooks are hurting, but that’s only one aspect of what this is about. They’re being asked to do something that feels illogical and hard for others and, in spite of obvious signs of social collapse around them, that feels like a bridge too far.

Two things have been true from the beginning of our country’s history. First, white Americans, across lines of class, have been consistently offered an elevated place in racial hierarchies. And secondly, white Americans, also across lines of class, can’t make it a decade without routinely rioting and rising up against what they consider to be a totalitarian government that somehow exists primarily to hold them back.

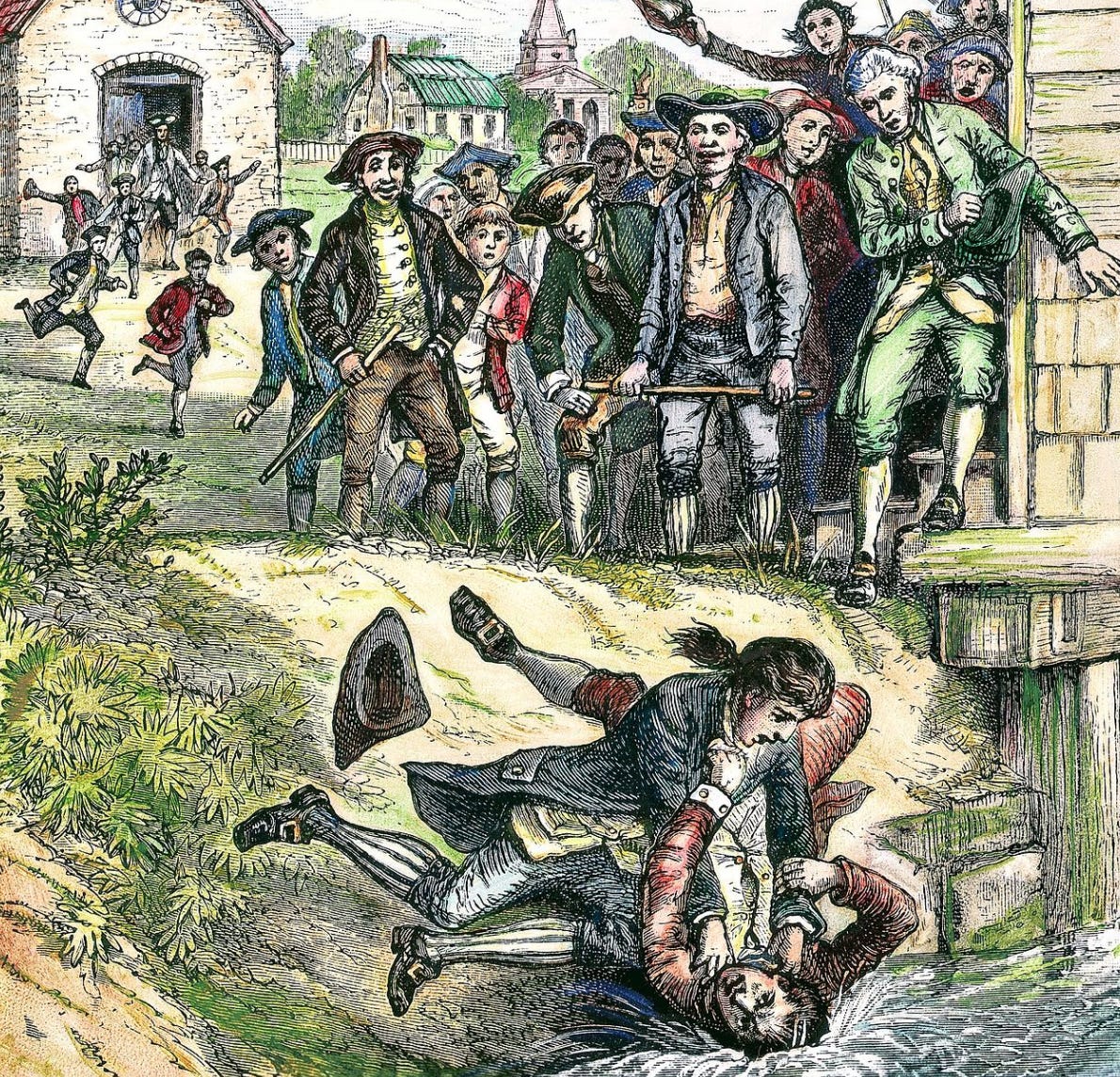

We are a nation built on and uniquely responsive to white people’s anger. Ours is a country whose Constitution was influenced by the recent memory of Shays Rebellion and the angry Massachusetts farmers who carried it out. Ours is a country whose borders and boundaries were shaped by whatever Indigenous lands frontier whites wanted for themselves. Ours is a country whose entire modern federalist identity remains inextricably bound to the legacy of the Civil War and the effective dismantling of Reconstruction that followed.

We are a country built, to borrow the concept that Carol Anderson so effectively describes in her book of the same name, on White Rage. It is a rage less rooted in an ingrained hatred of those who aren’t like us than a fear of losing status, of losing autonomy, of losing our ability to only do what we want, when we want it.

And so today, white people are marching on state capitals in non-socially-distanced-clumps and calling on all patriotic Americans to defend their hair salons by any means necessary. A few years from now, we’ll be angry about something else. The story will be the same though. White America remains perpetually aggrieved because we’ve been offered an unsustainable bill of goods, the lie that we aren’t actually dependent on each other.

Back in the halcyon days of 2015, when anti-vaccination culture was a troubling but still niche threat and relatively few assault rifles were being displayed outside state capitals, Elizabeth Bruenig published an unintentionally prescient piece in the New Republic. In it, she presented two different recent studies, one about particularly committed American anti-vaxxers and the other about healthy young Swedes who voluntarily received H1:N1 vaccinations not for their own benefit but to protect their more vulnerable neighbors. Citing 2014 research from sociologist Jennifer Reich about the former group, Bruenig offers a telling summary:

Parents who opt out of vaccines come to their decisions by prioritizing the very virtues American culture readily recommends: freedom of choice, consumer primacy, individualism, self-determination, and a dim, almost cynical view of common goods like public health.

Put differently— the least compassionate and community-minded among us have never been monstrous anomalies, but mere reflections of who we’ve always been as a country.

By contrast, the relative effectiveness of the Swedish government’s voluntary H1:N1 vaccination campaigns in 2009 were hugely aided by that country’s relatively high trust in government and other shared institutions. It is the kind of sentiment that you may have seen in a recent viral post from the Danish Covid doctor expressing her gratitude for the opportunity to pay back the investment previous generations of Danes made in her and her peers. Neither of these countries are perfect (and the Swedish government’s response to Covid has been uncharacteristically cavalier and critique-worthy) but you get the point.

The problem with trust, of course, is you can’t just ask for it. It’s built through time, through dependability, through a lifetime of caring actions. People trust their government when their government has consistently shown up for them. People are more willing to do hard things for those they’ve never met if they’ve experienced the comfort and support from living as part of a collective group.

The mess we’ve gotten ourselves in as a country is that we’ve offered such a limited promise to every one of our fellow citizens. For Black, Brown and Indigenous America, we’ve never offered much of a promise at all. For white America, we’ve offered the promise of rugged individualism, the opportunity to be left alone. In all cases, we’ve never been especially good or consistent at offering a helping hand. The angry farmers of Shay’s Rebellion weren’t just toxic white people— they were broke and getting ripped off and rightfully felt like they were on the margins of cosmopolitan colonial power centers. Their government wasn’t showing up for them, so they didn’t show up for their government, let alone for their Black or Indigenous neighbors.

And so here we are. We’re a month into what, for anybody alive today, is an unprecedented experiment in shared sacrifice. The irony of course is that in many ways it is working— actual lives are being saved, actual curves are being flattened. Because that’s the case, though, many Americans don’t have daily evidence (bodies piled up in the middle of the street, loved ones dying left and right) of a threat to be feared, so instead they are asked to trust expert reassurances that this sacrifice is worth it. As they attempt to do so, our country’s lack of a real safety net is putting more and more people at risk by the day. $1200 checks disappear to rapacious landlords as soon as they arrive in checking accounts. Small business loans get gobbled up by chain steakhouses and corporate sandwich shops. My heart aches so much at the number of my neighbors whose anger is reserved for this temporary experience of sacrifice and not deep injustices. But then I think about the country in which we all live and it’s clear that we’re all simply following the lessons we’ve been taught our whole lives.

And so I run downtown, through this odd, preserved time capsule of our own era. I pass opportunity after opportunity to express my unique personality and find self-actualization through consumer choices. I pass by public-appearing but privately-owned squares. I pass by the old Schlitz Brewery, long shuttered, now home to various white collar and creative class offices. At the edge of the facility, right off the river walk, the owners have put up a selfie station where I can celebrate this city by celebrating myself. I see very little evidence that the country or state or city in which I live has many aspirations for me that go beyond cultivating my individual “brand” or spending money.

I’m heartbroken that I live in a country where all of us, but especially those of us who are white, can believe more in the promise of every-person-an-island than in our connection to each other. I’m angry that our only shared collective experience during this time might end up being that we all watched the same mean-spirited, nihilistic “let’s laugh at the funny rednecks with their tigers” documentary on Netflix. But I also know that it took hundreds of years to get here, and so I have sympathy and love for how many more times we’ll have to reach our hands out before others can trust that they’re worth holding.

So I get home from my run. I send a little bit of money (which is in shorter supply than it once was) to mutual aid funds for Black, Latinx and Indigenous families. I reach out to friends whose communities have been impacted the most, that are always impacted the most. And then, as quixotic as it seems, I log back onto that Facebook group, with all its vitriol and fear, and I send messages to a few more angry, sad, scared white people, not because my outreach can save or transform, but because I know that the muscles that connect us to one another have atrophied. The exercises I’m doing to build those muscles back up may be small, may seem silly, but that’s what it takes to start building them stronger.

We have never been in this together. But we have to be.

Image credits here

This week’s song (Happy Belated Ruination Day y’all!): “April 14th Part I” by Gillian Welch (hat tip to Luke O’Neill’s consistently stellar newsletter, which tipped me off to that whole deal)