Does your tiny, insignificant protest matter?

On the power of showing up, over and over again

One of my closest friends from college had radical parents. Truth be told, a lot of my friends from college had radical parents (that’s the kind of college I attended) but his were especially radical. He grew up in a commune with two other families, a labyrinthine farm house tucked in a wooded corner of Cincinnati. That’s the kind of radical upbringing we’re talking about here.

My friend’s mom and dad were always protesting. In the streets. In the union halls. At home. I’m sure that many in their community dismissed them— of course those crunchy bleeding hearts were protesting again. What was it this time? The ozone layer? Nuclear weapons? The Equal Rights Act? Did they really think they could make a difference?

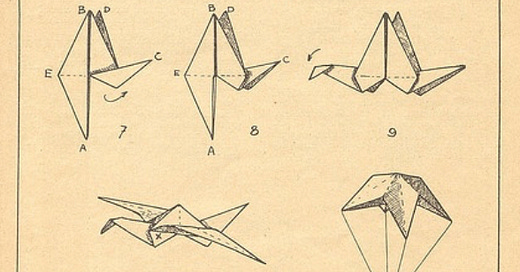

Back during the second Iraq War, my friend’s ever-protesting father started folding little origami peace cranes and mailing them, one at a time, to the White House. Just about the tiniest act of protest imaginable. Because he didn’t want to be wasteful, he utilized whatever scraps of paper were already lying around the house, including flyers for an upcoming concert by his wife’s feminist women’s chorus.

After the crane mailing had gone on for a decent spell, my friend’s origami-folding father received a letter from the White House. It was from the Secret Service agent who had opened all of his packages. The epistolary cop was cordial. He thanked my friend’s dad for the invitation to the concert, but expressed his regrets that neither he nor his boss would be in Southwest Ohio that particular evening.

My friend’s father did not single-handedly stop the war. The secret service agent who unfolded his swans didn’t even fully process that he was attempting to stop the war.

He wasn’t alone in his failure. None of us stopped that war. It raged on until it petered out under the weight of its own illogic.

So what’s the use, then? Why protest at all?

It’s an evergreen question, but it’s also a red-hot, present tense question.

Why should Americans who mourn the Israeli military’s atrocities in Gaza call Congress, sign petitions, and take to the streets? Do we really think that the U.S. will ever stop giving Israel 3.8 billion dollars in military aid? Aren’t we all just rolling so many boulders up so many hills in perpetuity?

Why even try?

In 1981, U.S. President Ronald Reagan articulated his policy of “constructive engagement” with the right-wing government in South Africa. The basic argument was that, because South Africa was a stalwart U.S. ally against communism, it was unthinkable that we’d ever put meaningful pressure on the Botha administration to end apartheid. In Reagan’s words, “can we abandon a country that has stood beside us in every war we've ever fought, a country that strategically is essential to the free world in its production of minerals we all must have…?”

The answer to that question was supposed to be self-evident. Of course we couldn’t, regardless of whether the government in question was operating in abhorrent, inhumane ways. Not if it went against the interest of U.S. economic and foreign policy. Not if there were “minerals we must have” at stake. To hope for anything different was monumentally naive.

At the time Reagan delivered those remarks, the U.S. campaign against apartheid— which pressured U.S. companies and universities to disinvest from South Africa— had been plodding along steadily since 1966. The movement was, at varying points, vibrant, moribund, fractured, and resolute. It was derided both for its tactics (the boycotts against companies doing business in South Africa were never sufficiently widespread to actually effect those company’s bottom lines) and its theatrics (there’s plenty to critique in visuals of privileged college students erecting Soweto-cosplay shantytowns on their campus quads).

I grew up during the anti-apartheid movement’s peak. Elementary-aged me didn’t worry about issues like movement efficacy. I just tagged along with my parents to various benefit dinners at our church, fully confident that a nation half a world away cared about what a motley collection of Nation subscribers and organic farmers from Lewis and Clark County, Montana thought of their government. I’m now aware, however, that for many on the front lines of that movement, those efforts frequently felt downright Sisyphean. They wondered whether their little personal consumer boycott or their daily calls to congressional switchboards or their micro-campaign to get their school or municipality to pass an anti-apartheid resolution accomplished anything other than ego-gratification.

But all the while, amidst all of those internal doubts and external criticisms, here’s what happened. The movement kept growing. Not like a rocket, but like a train. Steadily. It kept growing because Americans who were previously disengaged encountered— in their workplaces, schools, churches, temples and mosques— friends and neighbors who were involved, who took small daily, weekly or monthly actions. And that encounter, in turn, demystified the whole idea of “getting involved.” It provided an entry point for new voices to join the fight.

Too often, when we think of movements as having momentum, particularly in a social media age, we imagine explosive, viral energy. One day a hundred people are at a protest, the next day the crowd numbers a million strong. We’ve seen the risk of those hockey stick shaped moments, though. They can burn out fast. Too often, we forget the power of movements that are sustainable, that consist of people doing small, meaningful actions over and over again, that enable simple rituals to spread person-to-person and community-to-community.

Back in the 1980s, while citizen activists were each doing their little bit to keep the anti-apartheid movement in the public consciousness, a connected network of activists and staffers on Capitol Hill pressured Congress to break with Reagan’s “constructive engagement” policy and instead issue sanctions against the South African government. For years, that felt like a pipe dream. But the calls kept coming in. Congresspeople bemoaned that they couldn’t go to a baseball game without constituents chiding them about South Africa. The tide started to turn. And it turned not just because more and more people got involved, but they stayed involved.

In 1986, Congress officially passed sanctions against the apartheid regime. Although Reagan initially promised a veto, he backed down. It wasn’t the singular blow that brought down the minority White government, but it was a key piece of the puzzle. It was an absolutely massive victory, one that was unthinkable just a few years previously.

Years later, Cherri Waters, one of the Capitol Hill staffers who led the inside game on the sanction resolution, reflected on the secret power of the disinvestment movement. Its impact wasn’t to be found in any of the individual victories along the way (this or that hippie-ish college town passing a city proclamation against apartheid). It was its quiet persistence. What mattered was that so many Americans woke up every morning and thought of themselves, not passively but actively, as anti-apartheid activists. In Waters’ words, “it's like the cliché, ‘think global, act local.’ [In the case of the] divestment campaign.. the most important element of that [was] "‘act local’ because it gave everybody something to do. And movements need something for people to do”

Movements need something for people to do

The world as we know it operates on a very specific logic, one that we can be tempted to assume is inevitable. For years, wise, cynical minds couldn’t imagine a world where the apartheid regime would cede power. Today we believe that there will never be peace and justice for all the peoples whose hearts, home and heritage are in the Levant. But no cultural or political logic is inevitable. That myth persists when those of us who long for a different world assume that our actions are too small and our voices too disparate and we give up before we even begin.

Do you know why I’ll never forget that story about my friend’s father and the paper cranes? It’s because it was a beloved legend, passed around tenderly by activists on our campus. On so many days when our efforts felt cartoonish and impotent— when our sit-in at our congressperson’s local office failed to attract media attention, when we marched with thousands in New York and D.C. but the war raged on any way, when our desire to stop the invasion was drowned out by the stress of day-to-day life— I thought about the cranes. Here was somebody’s dad in Cincinnati, not giving up, just folding and folding. As long as he was still at it, that meant that opposing the war wasn’t insane. It was normal. It was a ritual. It was something I— and we— could keep doing.

This is all to say, if you, like me, are heartbroken over the assaults on Gaza right now, if you believe that that the Israeli military’s offensive will bring about neither peace nor justice, you’d be forgiven for feeling hopeless. Yes, you’re supposed to contact Congress. Yes, you’re supposed to attend marches. Yes, you’re supposed to sign petitions, or participate in boycotts. But will that ever make a practical, tangible difference? Will that impact the political calculus of a hard-right Israeli government who is currently offered unconditional support from the United States?

If we give up, the answer to that question is already pre-determined. So what’s the risk, then, in putting one foot in front of the other, in doing our small, insignificant, daily actions, in inviting others to join us as well? What’s the risk in marching in every protest we can attend, in calling our Congresspeople every morning, in talking to every friend curious enough to engage us in conversation? What’s the risk in holding heartbreak and hope in our hearts at once, in guarding against both Islamophobia and anti-semitism, but not letting our humility keep us from action? What is the risk in ignoring the eye-rolls and the cynical voices in our own heads who claim that none of it will make a difference?

If the alternative to our collective trying is a world that is all but guaranteed to be filled with grieving parents and needless death, the question isn’t how we can have the temerity to believe that our tiny actions matter, but how we can consign ourselves to the nihilism of not trying at all.

We will keep going, and if we do so, our tiny, presumably insignificant actions will not go unnoticed. Others in our communities will see that we are still plugging along. They will see our little version of those tiny cranes. They too will remember that their hearts are driving them to action.

They will join us.

And we will all keep going.

Until the bombs stop falling from the sky.

End notes:

I often use this as a space to share a song of the week, but this time around I want to share a few opportunities from amazing members of The White Pages community. I’ve never done something quite like this before, but I recently noticed a glut of exciting things being offered by folks whom I trust and have helped inform this space.

One of my favorite models of regular, daily action and reflection on Gaza has been . If you’re not already reading her newsletter, , I highly recommend it.

I linked to them up above, but the U.S Campaign for Palestinian Rights has been a particularly helpful source of information about opportunities for action (again, if you, like me, are a U.S. resident who believes in the need for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza).

The powerhouse anti-racist activists and socio-emotional educators, Future Cain and Karen Fleshman, are hosting an interracial sisterhood retreat from December 14-16. For more information (and to apply) check out the information here. They are also hosting an information session tonight at 6:30 PM Central. Registration link here.

One of the people who has taught me the most about how to show up in the world is my friend, Athena Palmer. In addition to being an exceptional person with profound thoughts about how to build a better world, Athena is a truly talented coach who is currently offering a holistic leadership coaching for new clients (especially recommended for folks navigating big changes, feeling stuck in patterns or experiencing burnout). More information here (and if you’re interested, you can contact Athena at athena@noduckscoaching.com).

Oh, and if you want to ensure that this space continues to exist, thanks for considering either subscribing and/or pre-ordering The Right Kind of White ( a very good book that I think you’ll enjoy; pre-orders come with fun thank you gifts.).

I found this to be a very encouraging article. All of our collective and individual efforts shift the world, even if we don't see immediate results. I regularly do one person acts of boycotting. Even when the act itself has no noticeable effect, the conversations I've had with others about my actions have planted seeds for change and action. I believe that these conversations are the foundation of powerful grassroots movements. I appreciate you sharing your thoughts and generating discussion.

My friends and I had the same discussions over many protests we experienced and then everything went back to its norm. Our protests were about environmental issues. Many of my friends got beaten and threw to jail and were followed for years by security police. Then the question emerges, what is the point of doing that when the forests were still chopped and those protestors lost their lives in constant fear and threats.

We don't actually know. Just like the story of that father with the origami crane. Thank you for writing about that.

And at the same time, I saw how the mentality of our community changed after our friends' lives were ruined. There were people started caring about them, about the issues. Young people read and learn what forests mean (such beginning education, need to be self-educated), what fresh air means, what less noise means. The younger people I met didn't go to protests. Many of them became research fellows and scientists to talk loudly on TV and interviews explaining what that means with pollution. I learn that the seeds come from those ruined lives. I learn that I also keep writing because of those ruined lives. The forest is gone. We didn't save any of it. But we learn to keep trying.

With this war, I am doing the same. Learning the same. I try to talk about it whenever I can. I want to understand and discuss the misery of those so far away from me.