Down in the Valley

Some tragedies are acute, some tragedies are chronic. Most tragedies are preventable.

My stomach hurts so badly right now, just a concentrated knot of dread and worry.

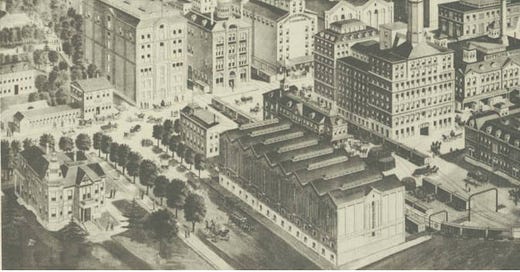

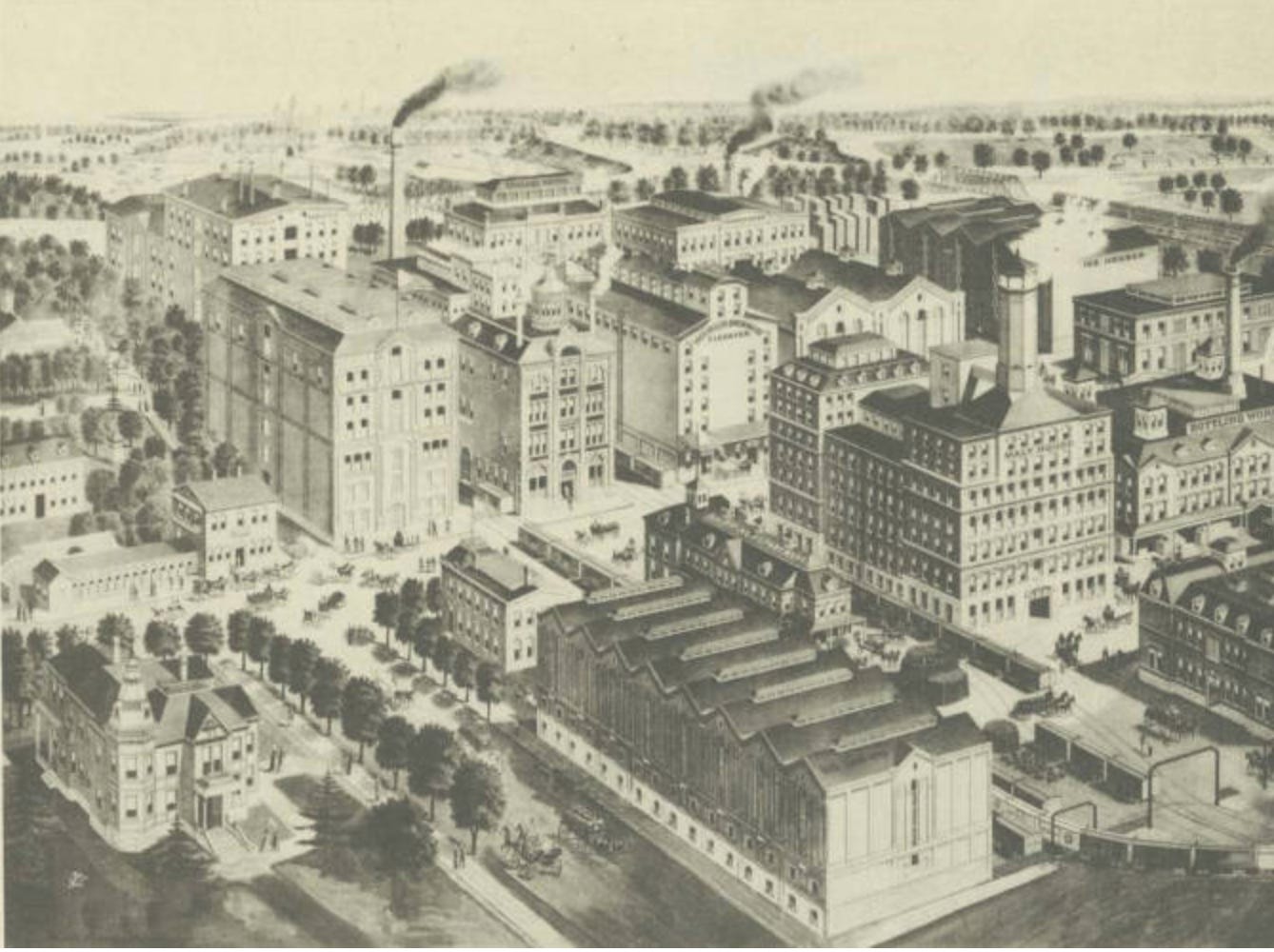

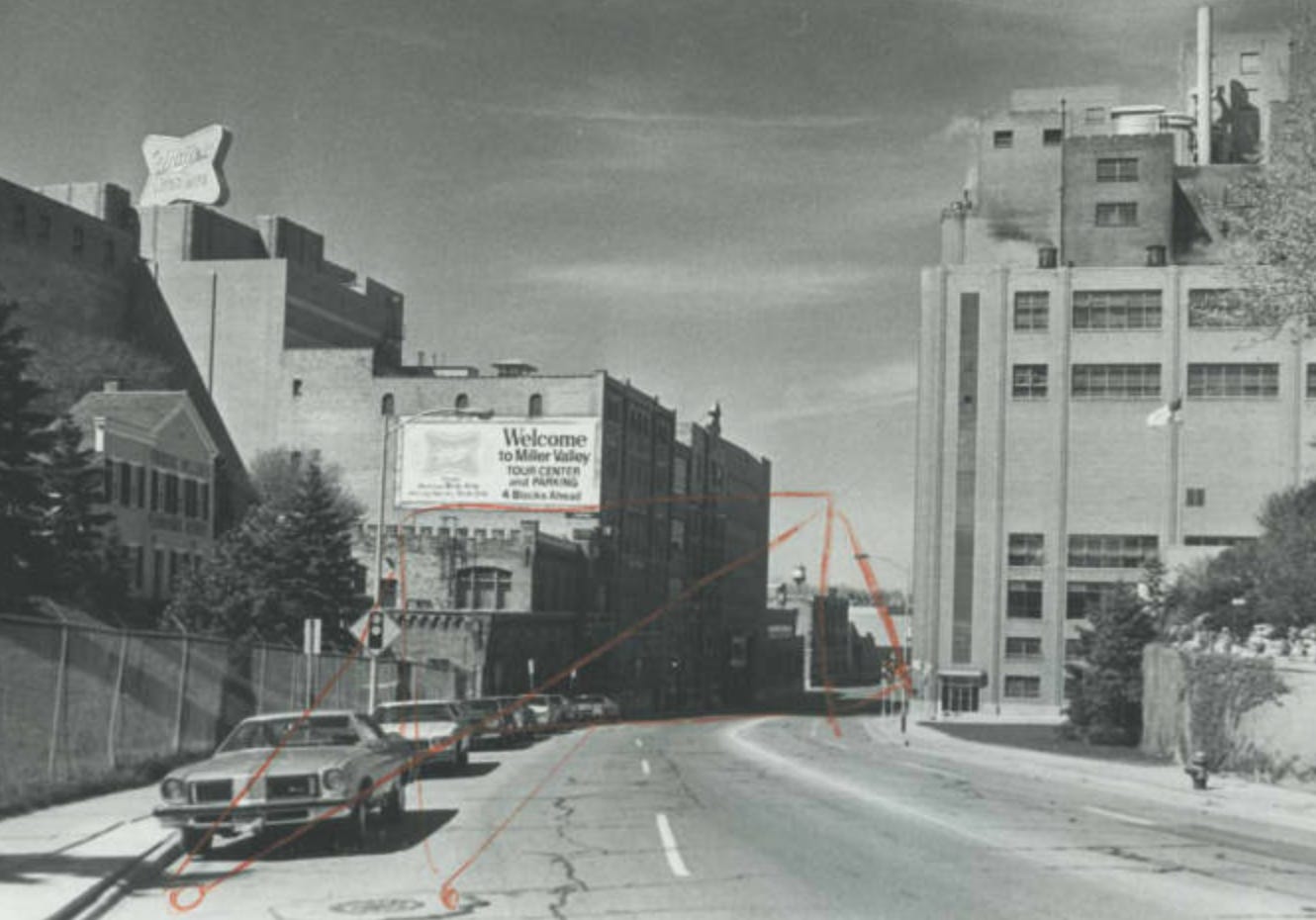

Yesterday, a few miles from my house, a former employee walked into the old Miller Brewery with a couple guns and started shooting. Six people died, including the shooter. They call that part of town Miller Valley. It looks very much like the story this city wants to tell about itself: A weathered but still-charming factory town. A place where Industry and Labor offers the promise of a good life. State Street winds through the complex, up a tree-lined twisty hill. At one point, you pass under an overpass where you can see the beer conveyer line above you. There are arches and historic placards and a gift shop. In December they cover the whole scene in Christmas lights. It’s really quite lovely. “Schlemiel! Schlimazel! Hasenpfeffer Incorporated!”

There’s an elementary school right there in the valley. It’s so close to the brewery that the whole place smells like malt. It was one of about a half dozen neighborhood schools that were on lockdown yesterday. The hospital where my wife usually works was on lockdown too. She wasn’t there at the time because she was off-site at a training about the opioid epidemic. At some point in the afternoon, everybody’s pagers went off at the same time— a room full of doctors shocked out of their engagement with a generalized tragedy to alert them to a specific one.

It’s all very bad and very sad and if you don’t live here there’s only a fifty/fifty chance you heard about it because, well, six person mass shootings are no longer newsworthy.

You’d also be forgiven for not noticing because there are so many other very bad things about which to worry, each of them individually enough to cause a decent-sized angst-ache. We might be on the cusp of a pandemic. Twenty five are dead already from government-fueled sectarian violence in Delhi. The Democratic Party is telling me that their convention here this summer is most likely going to descend into chaos. The stock market is dropping. It hasn’t been a good week.

If you’ll forgive an extended allegory, there was some other recent news that you may have missed.

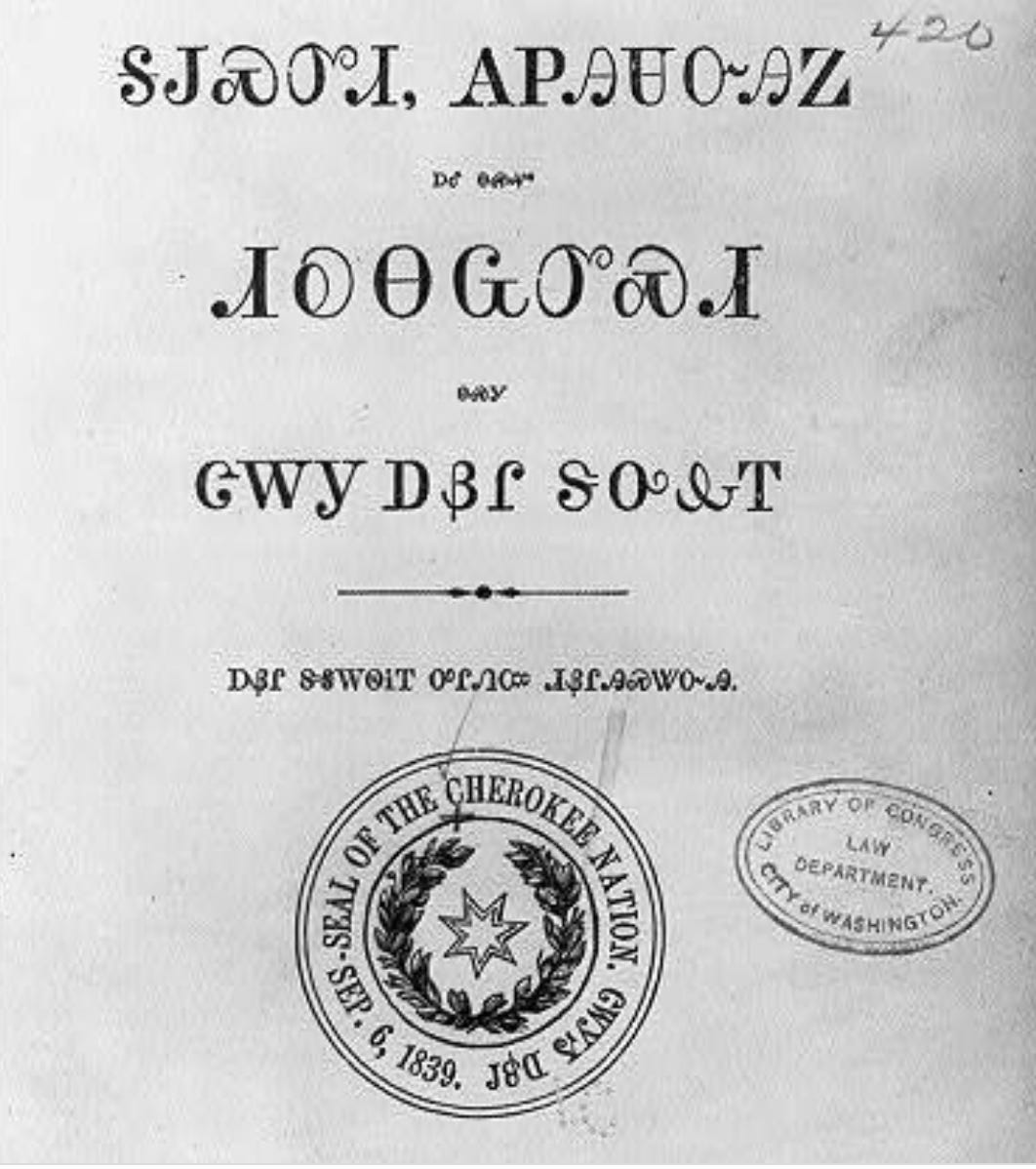

At some point yesterday, Elizabeth Warren sent a letter. It was earnest and thoughtful and extremely long— twelve pages. It was written in response to an equally earnest and thoughtful open letter from 140 Cherokee citizens (as well as roughly 80 Indigenous supporters from other Tribes). Warren’s was clearly an apology, though that wasn’t actually one of the demands requested in the open letter. The Cherokee leaders were writing to articulate the damage to tribal sovereignty that had been caused by Warren’s long-standing claim of Cherokee heritage. They asked Warren to issue a statement that would acknowledge three things:

Like many other white families, your family story of Cherokee and Delaware ancestry is false and it was wrong for you to repeat it as an adult. You have had the genealogical evidence since 2012. Stating you do not qualify for citizenship is not enough; the truth is you and your ancestors are white.

Equating Cherokee identity with the results of a DNA test was more than a misstep — it was dangerous. Your supporters and the public need to understand why. We ask that you explain that only tribal affiliation and kinship determine Native identity, and that equating Native identity with race and biology erodes the foundation of Indigenous sovereignty.

Claiming Native identity without citizenship, kinship ties, or recognition from Native communities undermines Indigenous self determination. As the most public example of this behavior, you need to clearly state that Native people are the sole authority on who is — and who is not — Native.

Warren did a number of things in her reply, many of them quite laudatory. She spoke passionately about issues of Native sovereignty. She talked about specific legislation she has supported on behalf of Indigenous communities. She was humble. She expressed remorse. She referred to various Indigenous activists and leaders who support her. She even responded directly to two of the three requests.

In that entire twelve page letter, though, there was still a bridge that Warren, a politician who has been praised by many activists of color for a better-than-the-average-white-person ability to listen and take feedback on racial issues, was unwilling to cross. She couldn’t fully acknowledge that she, like millions of white people, grew up believing fraudulent family stories of Native ancestry. She had been asked to do so not as a matter of personal atonement, but to serve as an example for other white people whose “family stories” have consistently eroded the ability of Tribal Nations to assert their sovereignty rights.

I don’t know Elizabeth Warren, but I can imagine why it might have been hard for her to take that last step. She’s in the midst of a bruising Presidential campaign, one where she, like all women running for President, has faced her fair share of direct or indirect sexism. She’s running against many men and women whose racial justice records likely seem more checkered than hers. She is, very clearly, trying to be humble and do the right thing. But there’s something about her family stories that feel too personal, too meaningful to give up. She can disavow the DNA test. She can even state present-tense that she knows she’s a white woman. And though, to an outsider, it seems like such an easy step to also say “I believed and perpetuated lies about my family’s stories for too many years” for her, that’s too personal, too hard.

The problem is that even when we as white people are earnestly trying to be good partners for justice, there are real implications from not taking that next step, from still defining what’s being asked of us as a bridge too far. We can always choose to dig in our heals; that is our right. But then we have to live with the results of that stopping point.

In this case, Warren might feel that the implication of not taking that last step is merely some minor PR blowback. Indigenous leaders know, though, that it has been these deaths by a thousand cuts to their sovereignty, the millions of white people who treat Nativeness as something they can try on when they feel like it, that have consistently cost their Nations both life and land.

When you hold power, the place you dig in your heals can set off seismic waves that can grow into destructive quakes.

Back here in Milwaukee, the feelings of shock and anguish are real. Six lives have been lost. Many more are impacted. But we live in an odd era, where we mourn in public, where we have been taught what to do at moments such as this by those who mourned publicly before us.

The rhythms of public behavior after an American mass shooting are so tread-worn that even commenting on their patterns has grown cliche. We’ve already memorized our parts. If you like guns and don’t like gun control legislation, you just say that it’s a tragic situation. If you do like gun control legislation, you yell at those that don’t for not saying and doing more. Somewhere, somebody on social media posts the Mister Rogers “Look For The Helpers” quote. Somewhere, somebody else the same Onion reprint about this being the only country where this happens.

I’m not saying that some responses aren’t better than others. I’m just saying we all know our parts.

For the past twenty four hours, there have been two conversations going on in this town, both of them rooted in empathy and pain. Civic boosters have been talking about how ours is a “small big city,” a place where everybody knows your name. The insinuation is that these ties to one another make moments like this sting more, but that it is what will make us more resilient going forward. There are already booster-y hashtags, of course. There are already t-shirts. We are #Milwaukeestrong and #Millerstrong.

These paeans to our connection to one another have lived side by side with another conversation, one which hints at how far apart we truly are. What began as murmurings amongst Black Miller employees grew to murmurings amongst Black Milwaukeeans more generally which were then finally confirmed by the news. The shooter was a Black Miller electrician. The media has officially reported that he had a pattern of disputes with colleagues. The rumors are that those weren’t just disputes, but that he suffered a long history of hate crimes at the hands of his co-workers. Nooses in lockers. Slurs. Harassment.

There is more right now that is unknown than known. The hate crime rumors could be totally false. And even if they are true, this wrinkle to the story is worth knowing not to excuse a man’s heinous actions, but simply to remind us that ours is a world where tragedies take many forms, but which always have a consistent root.

This is a town that doesn’t need to be told that it isn’t actually a close-knit Mayberry. Our inequities and divisions have been well-established. Our “most segregated city in the country” title is earned. Even if you’ve never set foot here, you aren’t surprised to know that our rust belt Epcot Center of a Miller campus straddles a poor Black neighborhood on one side and a leafy white suburb on the other. You already know that elementary school that smells like malt is virtually all Black and poor and that life looks very different for kids there than the mostly white Catholic prep school a couple blocks away.

Yesterday, my wife was alerted that she may be needed to respond to an acute tragedy. That alarm was warranted. But if we rang alarms for chronic tragedies around here, the ringing would never stop.

The vast majority of tragedies are preventable. We know this already. We know that mass shootings would wither to a trickle with tougher gun laws and more robust mental health care. We know that the generalized trauma of institutionalized racism and the immediate sting of hate crimes are enabled through human choices and actions; they aren’t inevitable either. And we know that there’s no God-ordained reason that sovereign nations find their right to self-determination so constantly besieged.

We remain stuck in this place not because of collective malevolence but because of collective fear. Each of us, particularly those of us with power and privilege, have a set of bridges that we refuse to cross. It usually isn’t the same bridge for each of us. Sometimes, we don’t know the true blessings of solidarity and connection and interconnectedness that could be true if we cross them, but other times we do.

It is easy for me to simply rail about other white people whose “bridge too far” is different than mine. My family doesn’t claim to be Cherokee, so it’s easy for me to get mad at Warren for being so intransigent on that point. My family has never owned guns nor had any emotional connections to the narratives around them. As a result, I can rail against the gun lobby and the white rural voter blocks that give it power.

If this seems like a set-up for a milquetoast call for simply showing empathy in the face of other people’s recalcitrance, don’t worry. We should most definitely fight against the bad stuff that’s easy for us to oppose. But we shouldn’t pretend for a second that the bridges we’re personally afraid to cross aren’t just as dangerous to the public good.

There was an acute tragedy in Milwaukee yesterday that was the ultimate fault of a single man. There was a larger tragedy, however, with a hundred causes. You might not be part of the problem when it comes to guns. But you might be part of the problem when it comes to patterns of workplace racism and the CEOs and unions alike that condone it. You might be part of the problem of segregated schools, of segregated neighborhoods. You might be part of the problem of militarized cities, of the many parts of places like Milwaukee where folks get used to carrying guns at least partially because they feel that the police are more threat than protector.

Like Elizabeth Warren, you might be a white person who knows all the right racial justice language. You might even have many leaders of color or Indigenous leaders tell you that you’re a humble listener, a good learner. That doesn’t mean that there isn’t another part of your life in which you’re digging in your heels. And wherever that place is, that’s where you’re causing the most pain.

The question isn’t “where are the helpers?” when we’re scared of the tragedy that’s already played out. The more interesting question is “are we the helpers?” when it’s our own fears that are about to set in motion a new tragedy down the line.

“Peace In the Valley” by Loretta Lynn

Photo credits here