How to win every fight without even throwing a punch

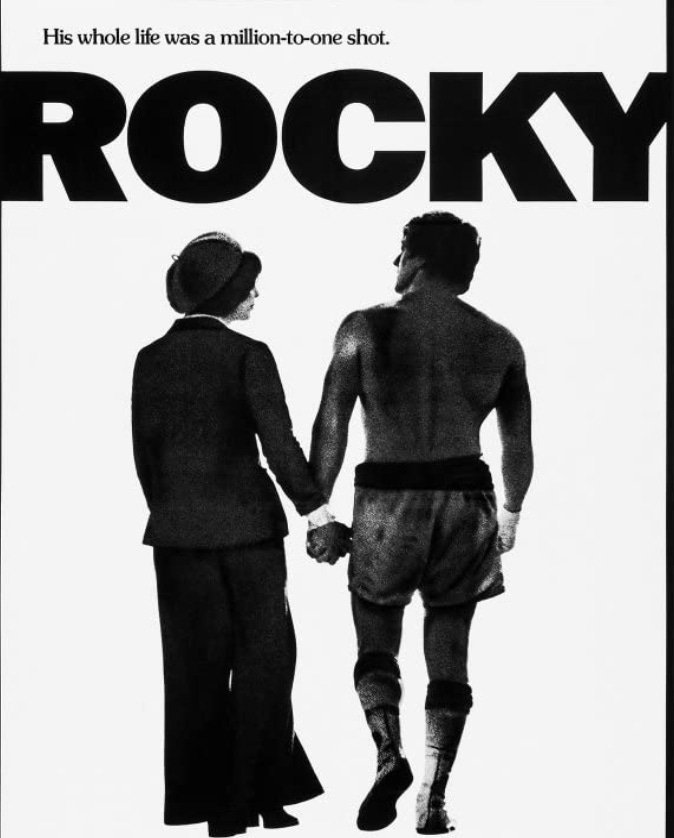

"10 Movies, 10 Stories of Whiteness" Issue One: Rocky and the paradox of punching down

Top notes:

It’s here! The first edition in the “10 Movies, 10 Stories of Whiteness” series. Here’s what you need to know:

If you’re not sure what this series is all about, here’s a primer!

You definitely don’t need to have watched this week’s movie (or any subsequent movies) to enjoy these essays. This week in particular, I promise there’s a ton here for those who have no interest in Rocky movies, boxing movies, sports movies, bro canon movies, etc. Really!

In case you do want to watch ahead of time (again, not necessary), the next movie we’ll be covering is Forrest Gump. Free subscribers will get a preview, and paid subscribers will get the whole thing (today’s issue is open to all).

This whole project is more ambitious than anything else I’ve taken on here. We’ve got great guest essays lined up, and each of my individual pieces are taking about a week of full-time research. While some issues will be partially paywalled, many won’t. That’s all to say, your support matters, and if you’ve been considering becoming a paid subscriber, today’s a great day to make the jump (besides the “you’re doing a very kind thing” of it all, the perks are also great: an actually-good online community, fun bonus essays, White Pages stickers in the mail… oh my!).

“This is the land of opportunity right? So, Apollo Creed on January first gives a local underdog fighter an opportunity. A snow-white underdog.”

“Look. It’s the name man…The Italian Stallion. The media will eat it up. Now, who discovered America? An Italian, right. What would be better than to get it on with one of its descendants?”

-Apollo Creed

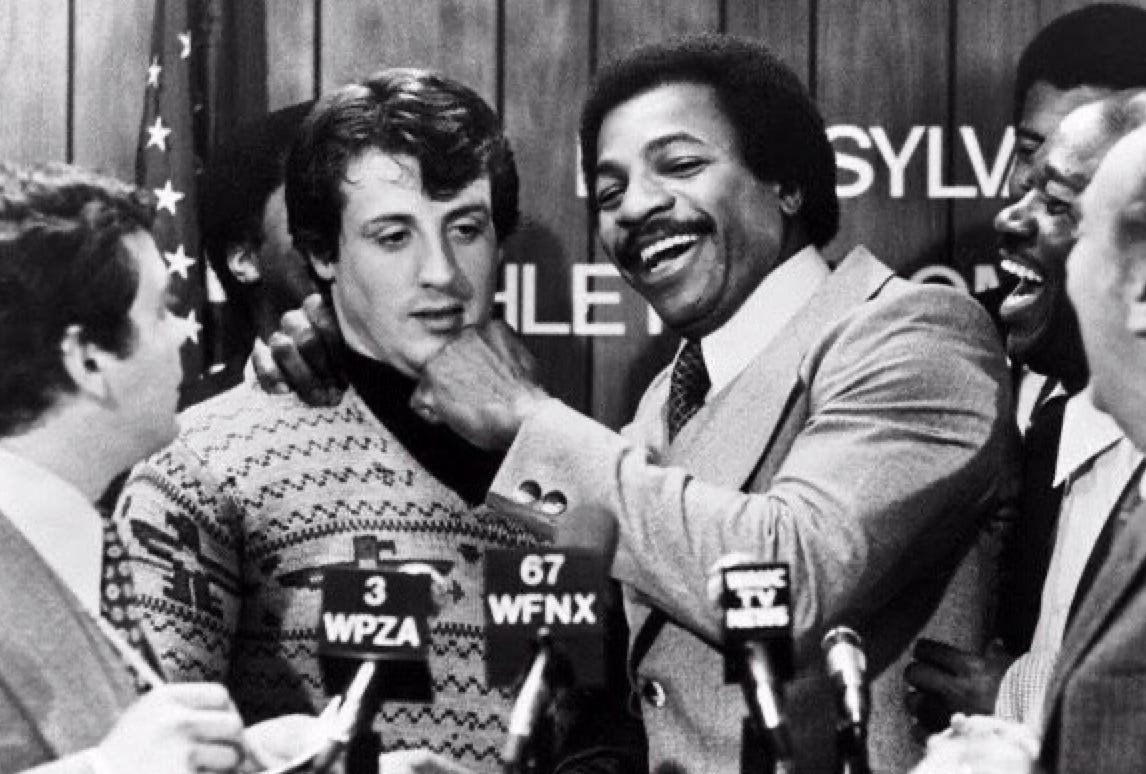

Have you heard of the Bible Riots? What a wild entry in the pantheon of Tragic American Event Names. They took place in Kensington, a neighborhood due north of Center City Philadelphia, in May and June of 1844. Like so many of our country’s darkest moments, the riots started as a fight about schools and then morphed into a general opportunity for busting heads and taking out grievances on a scapegoated other.

In the specific case of the Bible Riots, the victims of the head busting were mostly recently immigrated Irish Catholics. The assailants were mostly Protestants and their sympathizers (one of the instigators was Lewis Charles Levin, who would eventually become America’s first Jewish Congressman, but who built his political career on anti-Catholic crusading). If you’re familiar with any history of working class ethnic groups being encouraged to turn on one another, you already know the story. There were fears that the Catholics were gaining too much political power too quickly, that they were jumping their place in the assimilation line. There was general talk about “cozying up with the Whigs,” which is a phrase you don’t hear a lot these days. There’s a specific story, but again, you can already guess the outlines of it. Twenty people were killed. It was a big, dumb, tragic deal.

A bit more than a century later, the United States— a country with a long history of various ethnic groups getting their heads busted for not being sufficiently downtrodden— celebrated its bicentennial. A few miles south of Kensington, Queen Elizabeth presented a replica of the Liberty Bell to the American people. As far as “well done, old adversary, you sure did get us that one time!” gifts go, it was a very nice gesture. There was a lot of pomp and circumstance. No foreign leaders visited Kensington, though. By that point, the descendants of its former Irish residents had largely assimilated and decamped for the suburbs; the neighborhood that remained was a catch-all home for poor Philadelphians from a variety of ethnic backgrounds. It was the kind of place that wasn’t supposed to be the setting for an iconic bicentennial story.

But in a fictionalized version of 1970s Kensington, an unlikely hero strutted up and down trash-filled streets. He was a boxer, though not an especially talented one. He was also an enforcer for a neighborhood loan shark, though he was even worse at that (on accounts of being too kind). And most of all, he was a soft-hearted romantic, though his corny jokes failed to impress the quiet pet store employee who was the object of his affection. He was, to be clear, a loser— a dimwitted but lovable palooka trying to survive in a tough neighborhood and an even tougher country.

Rocky Balboa’s gentleness set him apart from so many other 1970s depictions of White men at war with a changing world. He wasn’t a demon-battling Vietnam veteran like his fellow Pennsylvanians in The Deer Hunter, nor a malevolent monster like Taxi Driver’s Travis Bickle. He definitely wasn’t a vigilante unleashing his pent-up fury on post-apocalyptic crimescapes like Charles Bronson’s Paul Kersey or Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry. Yes, Rocky Balboa was another in a long line of Sad White Heroes, and yes he punched people for a living, but when he wasn’t doing that he was talking to his pet turtles, offering words of encouragement to Kenington’s resident “doo-woppy guys singing around an open fire,” and making sure neighborhood children got home safely. It may be a slight distinction, but that doesn’t mean it wasn't intentional.

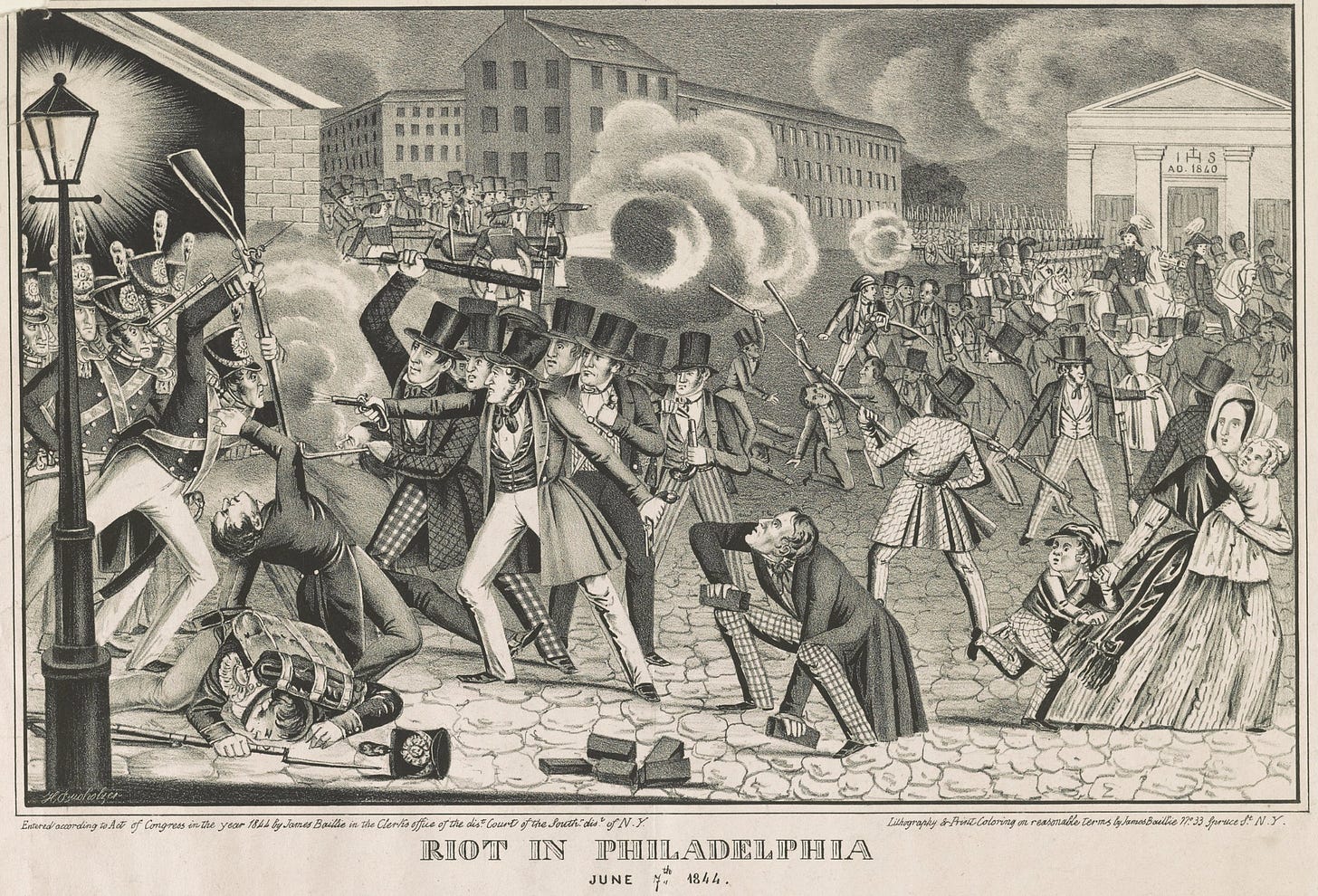

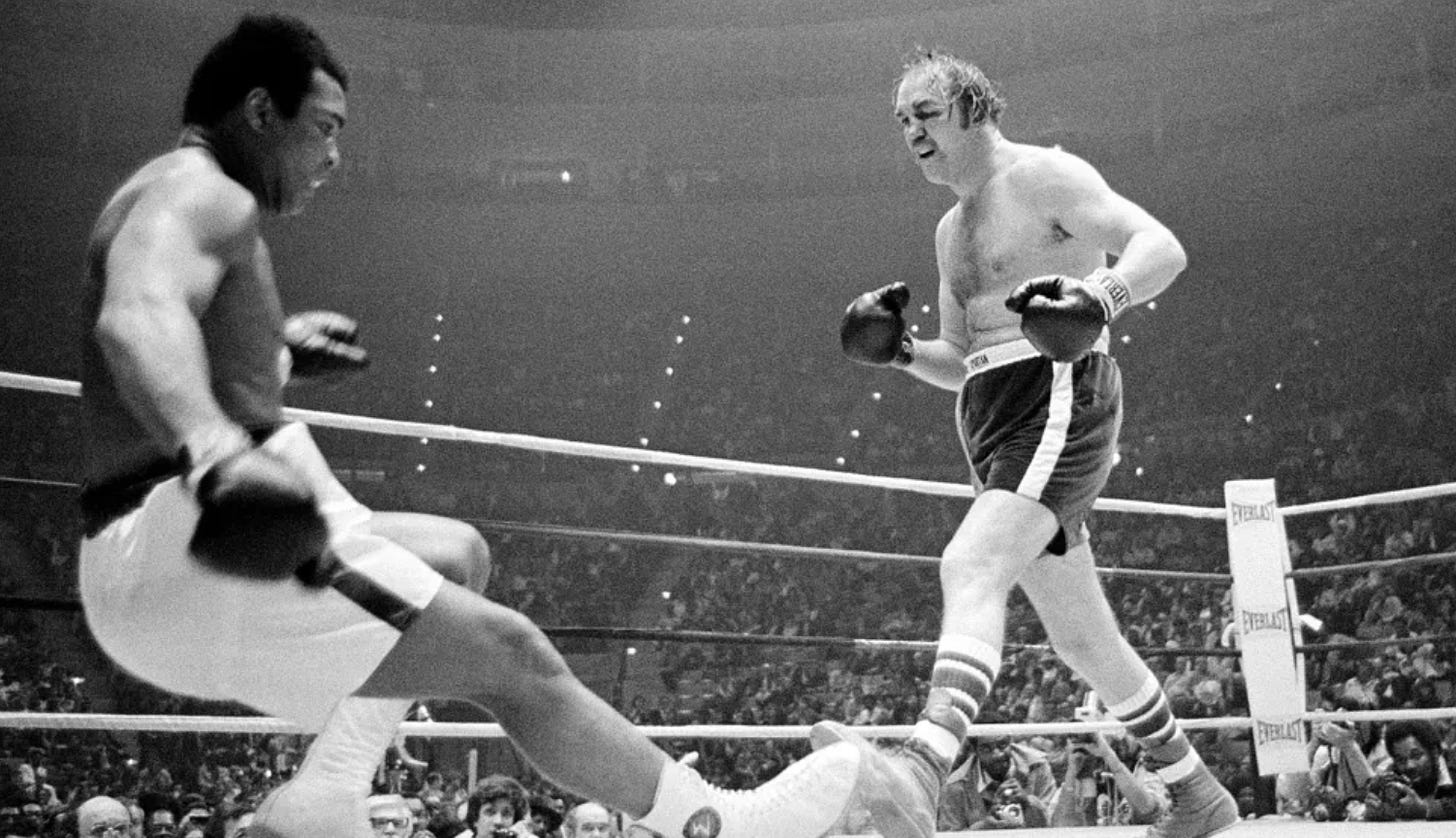

Sylvester Stallone— the man who would both create and become Rocky Balboa— was a struggling actor and screenwriter when— on March 24th, 1975— he watched Muhammad Ali fight Chuck Wepner. Ali, of course, was not only the most successful boxer of all time, but a proudly Black boxer— outspoken about political issues, deeply committed to his Islamic faith, and known as much for his charismatic boasting as for his considerable prowess in the ring. Wepner, by contrast, was a balding, schlubby, Slavic brawler from New Jersey who had learned to box by scrapping it up with sailors from his hometown’s navy base. The decision to pit “The Greatest of All Time” against the “Bayonne Bleeder” was the brainchild of Ali’s legendary manager Don King, who dubbed the affair the “Give The White Boy a Break” fight.

The match was a stunt, to be sure, but it was a strategic stunt. Ali had only recently regained the heavyweight title, and King believed that— by playing up the racial dynamic between the champ and his opponent— he could get as many White eyeballs as possible glued to the spectacle. That particular reading of the collective White cultural appetite likely would have proven correct at any point in history (Whiteness has always loved seeing itself depicted sympathetically), but it was a particularly smart bet in the mid-1970s.

It was during those years that two disconnected phenomena— the hollowing out of the American working class due to consolidated corporate power, and a small but meaningful increase in opportunity for Black Americans spurred by a series of Civil Rights Acts and Great Society programs— were melded together into a Frankenstein monster of White resentment. America’s bicentennial decade saw anti-busing riots in Boston’s Irish enclaves, Nazi mobilizations in Chicago’s Polish bungalow belt, and the reign of “law and order” strongman mayors like South Philadelphia’s own Frank Rizzo.

Don King knew what he was doing in providing working class White America with a sliver of hope that their avatar— a jamoke from Jersey named Chuck— might offer them deliverance against a presumed wave of ascendant Blackness. It was no surprise that mostly White crowds packed movie theaters for closed-captioned broadcasts of the fight. Nor was it surprising that those crowds reached stratospheric levels of elation when the surprisingly tenacious Wepner somehow went toe-to-toe with the champ. Not only did Wepner knock Ali down, but he came within 90 seconds of “going the distance”— surviving all fifteen rounds. The crowd at Stallone’s showing went wild, and the man who would be Rocky Balboa raced home as quickly as possible.

Stallone wrote the first draft of Rocky in a feverish three-and-a-half day sprint. He knew he had the perfect story. It wasn’t the boxing of it all; an extremely small percentage of Rocky’s run-time is spent in the ring. It was the fact that King was right— Wepner’s story— of White people being left behind not by corporations but by halting steps towards Black equality— was a myth. But by God, what a powerful myth. As Stallone remarked, explaining why he was drawn to the parable of the Bayonne Bleeder, “[I mean, just] talk about stifled ambition…and people who sit on the curb looking at their dreams go down the drain.”

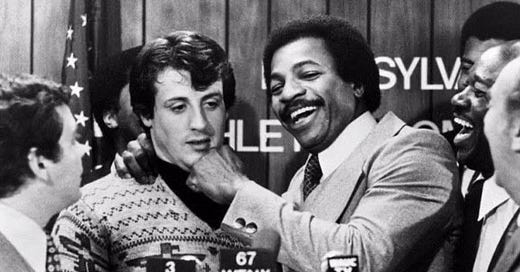

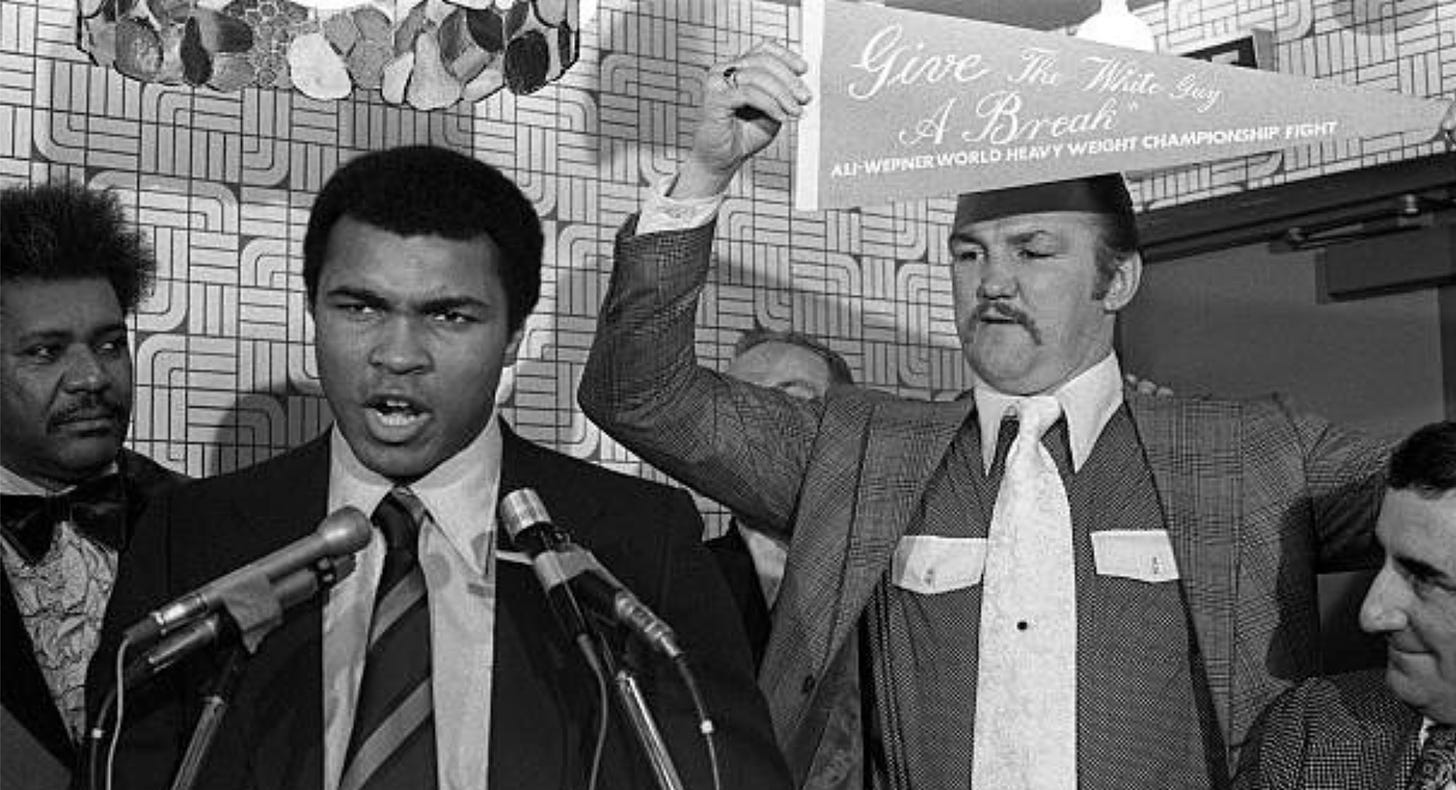

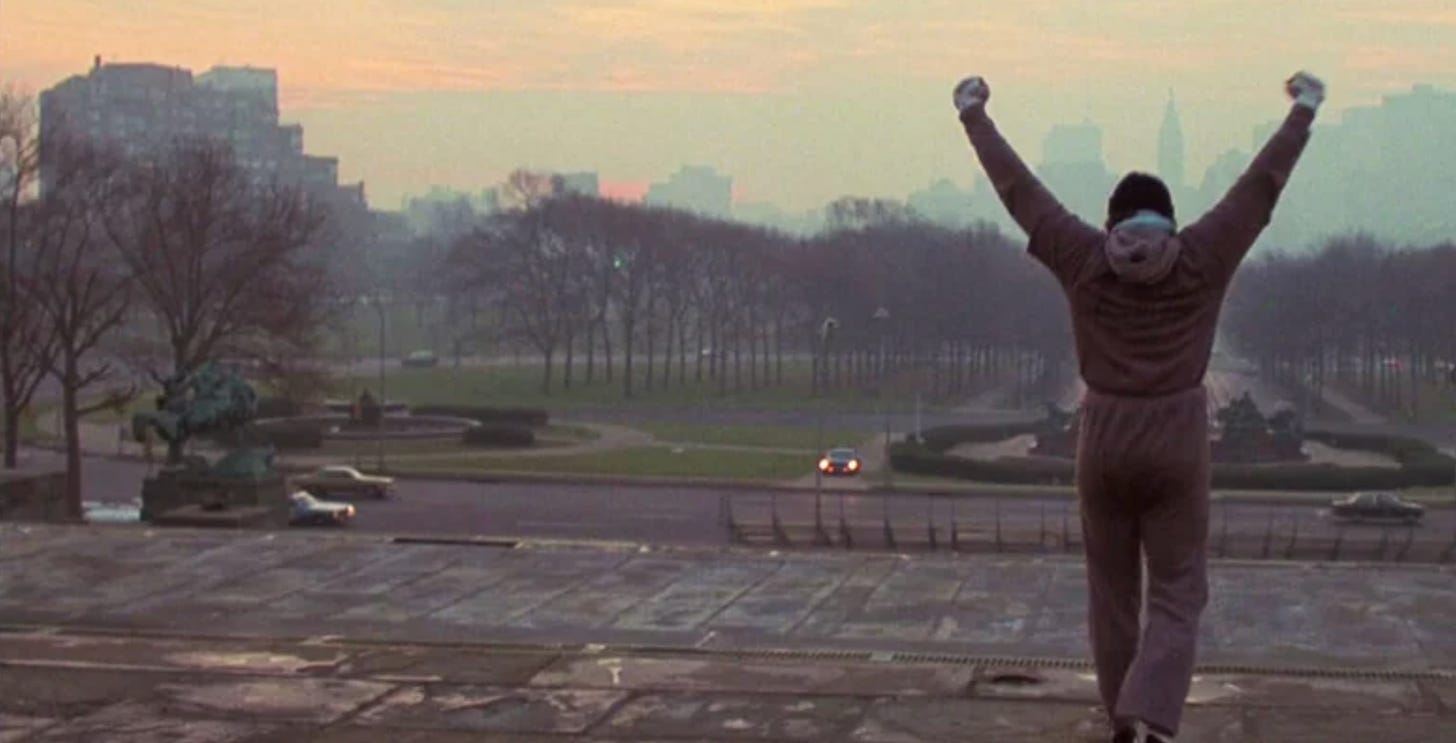

To their credit, Stallone and the team behind Rocky (Director John Avidseln and an absolute wrecking crew of a cast, including Carl Weathers, Talia Shire and Burgess Meredith) crafted a surprisingly effective film out of Wepner and Ali’s fourteen-and-a-half rounds in the ring. Everybody involved made a set of choices that kept a clichéd storyline (a literal David vs. Goliath tale) from feeling overly tired. It mattered, for instance, that the film doesn’t show any of Philadelphia’s iconic Center City sites (the City Hall, the Art Museum, etc.) until near the end of its run-time. Doing so makes Rocky’s Philadelphia feel small and claustrophobic, just one scene after another of him walking into a down-on-its-heels establishment and being informed that the person he wanted to see was “in a bad mood.”

Rocky also wouldn’t be as effective of a film without Talia Shire’s performance as Adrian, Balboa’s love interest. To be clear, hers was— in the not-so-grand tradition of male-led sports movies— an underdeveloped part. But by playing up Adrian’s unapologetic shyness, by making her presence known not through what she forces into a space but through what she conspicuously chooses to withhold, Shire hints at a deeper character (simultaneously sadder and stronger) than the one Stallone wrote for her.

As for Carl Weathers, who plays the Ali stand-in Apollo Creed, his role could have easily been a cartoonish parody. He could have played Creed as a cocky villain, strutting and pouting, all but daring the Gods to deliver his comeuppance. And yes, Creed is a flamboyant showman, rolling up to the film’s final bicentennial-themed showdown dressed as George Washington. But he’s never vindictive or cruel. In virtually every scene in which he appears, he’s holding forth in a boardroom (wearing a suit, surrounded by other Black men in suits) laying out sound business plans. It matters that Rocky Balboa’s Black foil is marked not by his cravenness but his corporate competence. He puts on a show when necessary, but only when necessary. He, a Black man, is already on top of the world. He doesn’t have to strive to raise his station any more, only to maintain it.

All of those choices are necessary for Stallone’s portrayal of Rocky to work. His White romantic partner has to be left without any societal agency aside from making herself smaller. His Black adversary has to be so triumphant that, over the course of the film, he barely breaks a sweat. And the Great White Hero, in turn, needs to actively reject a traditional image of White Rage. He needs to be goofy and deferential, never exploding, never losing his regular guy demeanor.

There’s a reason why Rocky was a massive hit. We, the White audience, need our heroes to be lovable losers more than we need them to be perfect deliverers of holy vengeance. Some of us may be afraid that we’re monsters, but far more of us are afraid that we’re just unexceptional schmucks. We need our protagonists to be gentle giants, because we don’t want to imagine that our own defense of privilege and position might ever require the infliction of cruelty. We want guilt-free permission to cheer at a movie that culminates in a Black and White guy literally beating each other into a pulp. We want to be protected by distant violence, but to keep our own hands and souls clean.

There will always be White rage, at least until Whiteness itself is transformed. From the first moments that conquistadors and buccaneers raped and pillaged their way through Indigenous villages, onward to January 6th and beyond, rage has been and will continue to be one of the primary ways through which our racial caste system perpetuates itself.

American White supremacy has always needed the pitchforks, but it has also required a critical mass of White people who aren’t overtly violent or angry but who will— at the first sign of civil rights progress— quickly raise the white flag and bow out. The 1970s weren’t just the era of anti-busing rioters and tough guy mayors. It was also the era of California Regents vs. Bakke, the first nice, polite, challenge to affirmative action to reach the Supreme Court.

At times—as was the case when Northern business interests gave up on supporting Reconstruction, or when affluent Orange Countians powered Ronald Reagan’s initial rise to power— the specific White people doing the bowing out have no objective reason to view themselves as being societal losers. At other times— as when poor and working class Whites are squeezed by rapacious capitalists— the alienation is real, though the culprit is misidentified. In every case, though, the pattern is the same. We feel like losers, we want to feel like winners again, and we blame Black and Brown people’s desire for basic civil rights for upsetting the natural order of things.

Over the course of multiple Rocky movies, we get to watch a polite, non-rage-filled, White male racial fantasy play out in full. At first, the ascendant Black man is humbled. Then, in the next installment in the series, the White man beats him honorably and reclaims his rightful societal perch. For the rest of franchise, the White man is rewarded with the greatest prize of all: The previous social order (one in which White guys get to win over and over and over again) remains intact, but the original Black adversary (now in a largely subservient, deferential position) offers him the gift of authentic affection and camaraderie. He gains all the spoils in the world and gets a Black best friend. Even when the series is eventually handed over to Black creative hands, the White guy still gets to stick around, now as a wise mentor for a younger generation. Long live the king.

Rocky Balboa moved out of his fictional Kensington as soon as he found fame and glory. Today that neighborhood’s real world equivalent is home to a familiar, teetering pile of inequities. Kensington in 2023 is many things all at once: there is unhoused Kensington, gentrified Kensington, working class Kensington, demonized Kensington, misunderstood Kensington, fentanyl and tranq Kensington. It is a place, like so many American places, where haves and have-nots share space uneasily, where we are reminded on a daily basis that we still so far from being a more perfect union.

There’s no single reason why twenty first century Philadelphia, like America generally, is still a deeply inequitable place— it’s not just because there were anti-Catholics riots in the 1800s, nor just because Sly Stallone once made a less aggressive White resentment movie. It’s because caste systems are knotty beasts, with more than one means of replicating themselves. Like a skilled boxer, White supremacy knows how to duck, weave and tire out its opponent. Most of all, though, it knows how to enlist us all in the fight, even those of us who think we’re gentle, even those of us who wouldn’t dare hurt a fly. “It’s ok,” we’re reassured, again and again and again. “They may tell you that you’re on top, but really, you’re losing. You can ball up your fist now. I promise. You can take another swing. Remember, you’re the real victim here. You’re punching up, not down.”

End notes:

This week’s song of the week:

Anybody want to run through Philly with a bunch of dudes on dirt bikes??? I thought so. Let’s listen to “Lord Knows/Fighting Stronger” by Meek Mill, Jhene Aiko and Ludwig Goransson.

And as always, you can find the collected “song of the week” playlist on Apple Music or Spotify!

In other news,

and I are still looking for a graphic designer to create a new logo for our beloved Flyover Politics Discord. Additionally, the two of us are both potentially open to individual contracts for merchandise designs. If you’re interested, please reach out (ideally with a website and/or portfolio samples) to the two of us simultaneously (garrett@barnraisersproject.org and eclenz@gmail.com).Also, while I have a few guest essays already lined up, if you’d like to pitch me on an essay idea for this series (you can find the full list of movies we’re covering here), feel free to toss me an email. Again, I’m at garrett@barnraisersproject.org.

This essay is a banger Garrett

I didn’t move to the states until the early 80s, so all I know about race and race relations in 70s here is through textbooks (not much) and what I’ve been picking up in books like Theresa Runstedtler’s Black Ball (Amazing book), or Radley Balko’s Rise of the Warrior Cop. So I have never looked at Rocky through the lens of race relations. Thank you for writing this.