If only John Wayne was still around, Portland and San Francisco wouldn't be in chaos right now

"10 Movies, 10 Stories of Whiteness" Issue Eight: The Searchers, the many myths of the American West, and reports on the death of American municipalities

Top notes: This is one of those essays that I originally intended to paywall, but it felt like it was in dialogue with a lot that’s happening in the world right now, so I decided against it. Don’t worry, paid subscribers, you’ll be getting a piece or two just for you coming up in due time (in addition to our weekly community discussions, of course).

For those who aren’t paid subscribers: Great news, here’s an another unpaywalled essay. This one is about cowboys and how we talk about homelessness and also Barbieland, with surprisingly no accessory jabs at a certain hit television show. In return, I’d love if you could lend a quick hand. Obviously, becoming a paid subscriber makes the biggest difference (since this is my job and I rely on subscriptions to afford child care) but so too does commenting, sharing and being a generally cool community member. Thanks in advance (and know that I’m sincerely glad that you’re here).

Coming up in the next few weeks: I’ve got a fun announcement issue lined up. We’re also down to only two movies in our summer film series. Legally Blonde and Hoosiers! Which one will I tackle first? Are we going to Indiana or Harvard Law? I honestly have no idea!

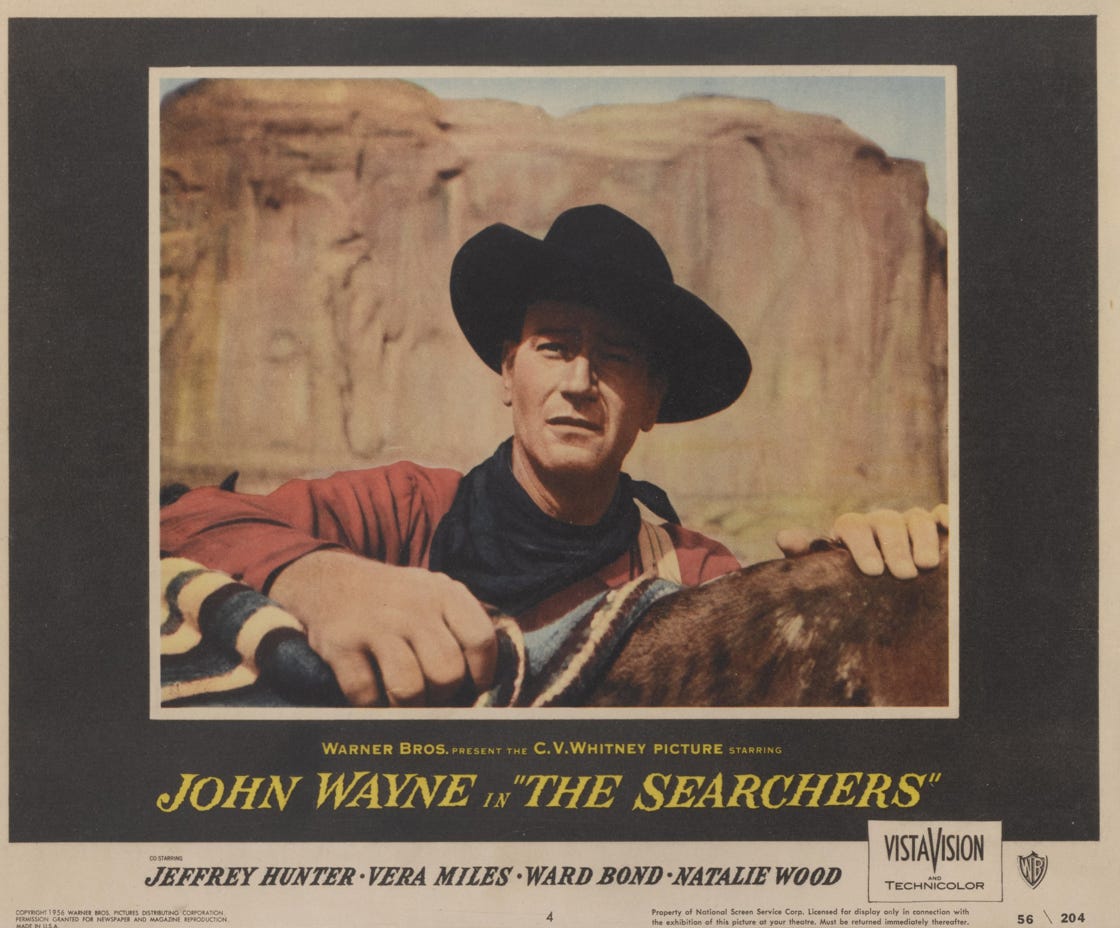

I’m not sure how many people are still watching The Searchers in 2023. Even if you haven’t seen it, you won’t need much exposition to develop a rock solid opinion as to whether it is your kind of movie or not. This is a film from 1956 in which the main character is hell-bent on killing as many Comanche as possible. That main character, by the way, is played by John Wayne, a long-time conservative hero and liberal pariah. What I’m saying is that we’ve probably all already picked our sides on this one. The culture war keeps the score.

You know who does love The Searchers, though? Movie directors and film buffs, particularly that specific generation of 1970s White male New Hollywood directors— your Scorceses, your Lucases, your Spielbergs— who idolize the film’s director, John Ford. Remember that scene in Star Wars where Luke finds that his Aunt and Uncle’s home has been destroyed? That’s a one-for-one rip off of John Wayne surveying the aftermath of a Comanche raid.

Professional film appreciators contend that The Searchers may be a product of its time, but that it’s also moody and dark and features an anti-hero with whom you aren’t supposed to identity. They’ll tell you that The Searchers is a character study about madness, and that madness is ugly, just as racism is ugly, and that there’s a difference between depiction and veneration.The UCLA Film and Television Archive describes the movie as “Ford’s inquiry into the psychosis of American racism.” That’s probably overstating it, but it’s obviously a well-made film with something on its mind. Personally, it’s hard for me to get over the bloodlust, but there you go. You’ve now heard both sides.

I really don’t want to talk too much about The Searchers, though. It is, in fact, a pretty racist movie. And maybe that’s the point. Maybe it wants you to know that it is aware of its own racism. Maybe it intends for that self-awareness to be subversive. Or maybe it’s a 1950s Western made by a White guy with a famously bigoted old grump in the starring role. Feel free to watch it! Or not! The question of whether it’s a good or bad film isn’t all that interesting to me. Instead, I’m fascinated by the story it’s telling, and why that story has had such a long cultural tail.

I am currently in the final stages of writing a memoir. At least in part, it will be a book about the places I’ve lived (in order: Littleton, CO; Clancy, MT; Columbia, MD; Missoula, MT; Richmond, IN; Crownpoint, NM; Stockholm, SWE; Chicago, IL and finally Madison and Milwaukee, WI). It’s an interesting list, or so I’ve discovered. Some of those places have been fairly easy to capture— suburban Maryland, the post-industrial Midwest, a cosmopolitan European Capital. Not so much the Western towns.

The American West isn’t a place, it’s a loosely organized confederation of creaky national myths. That’s a cliché, but it’s true, and the task of writing about Western places without resorting to other clichés has proved to be trickier than I expected. How do I describe a high desert mesa without talking about haunting vistas that seem to go on forever? Or describe the reservation town where I used to live and teach without prattling on about how the Diné are proud and resilient? How do I document the topography of Missoula, a city that is in fact bisected by the Clark Fork River, without mentioning that a river runs through it? It’s hard, or at least it’s hard for me. What do prodigal Montanans even mean when we talk about Big Sky Country? Do we think other places don’t have horizons? Have we measured?

For White America, the West has never just been a place. It’s always been the container into which we’ve poured our most strained attempts at grandiloquence. At least some of that is due to the fine art of Western hucksterism. The myth of the West was first told by those who had a vested business interest in encouraging new waves of White settlement. At various points in history, the snake oil salesmen spun stories of hills choked with gold, endlessly fruited plains that would surely never turn to dust, coastal and desert outposts whose perfect climates could cure any malady, and eventually Silicon Valley’s ability to save the world, one IPO at a time. The West, in these stories, was the gift that kept giving. It was the place where the ethnic White residents of overcrowded Eastern cities could find land and riches, but it was also where those residents of the new frontier (especially the men) could invent themselves anew. John Wayne wasn’t really a cowboy, of course. Few people are. He was a guy from Iowa named Marion Robert Morison. But that’s the point of the West. Even Marion could become The Duke.

“Go West, Young Man” was only one of the myths White America told about itself.. All that settlement and all that money-making and all that persona-creating doesn’t just happen, of course. White America lied, pillaged and massacred in order to make the continent its own. Subjugation of land, culture and human beings has always requires a myth to justify it, and the West was built on those sorts of myths as well. Yes, this is a land of beauty and grandeur and endless opportunity, but it’s also— the myth has taught us— a land of danger. It is a place where the land itself would have killed White people if we hadn’t tamed it. Even more so, it was a place whose original inhabitants would have either killed or assimilated us if we hadn’t struck first. It’s a useful set of myths, especially in the moments that White America wants to feel like we don’t have blood on our hands.

The Searchers is just one in a long line of justification myths. It’s pointedly not a classic, Joseph Campbell-approved hero’s journey. As the Eberts, Scorceses and Spielbergs will no doubt tell you, John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards is no hero. He is consumed by hate and mania, so much so that at one point in the film he almost murders his own niece. He is unrepentant and impulsive and stubborn. He’s not a fun hang, but he's not supposed to be a fun hang. In this case, his cruelty really is the point.

What matters, to the myth of the West, isn’t the hero, it’s the threat. And on that front, the movie is absolutely unambivalent. The film’s fictional band of Comanche really does stage a pre-mediated raid on the Edwards compound. They really are led by a shrewd and fiendish leader, the not-so-subtly named “Scar.” They really do kill Edwards’ relatives and kidnap his two young nieces. You’re supposed to notice the nieces. They exist not as characters but as empty vessels into which White patriarchal nightmares can be poured. The older niece is killed (and presumably raped), while the younger one marries the Comanche Chief and initially refuses to come home to White America. That’s where the whole “John Wayne almost kills his niece” plot line comes in. The ultimate threat, of course, is miscegenation. Better dead than red and all that. Kill the Indian, save the girl.

It’s not a subtle message, and of course it’s about gender as much as it is about race: The West is beautiful, but the West is dangerous. It is dangerous for White people generally, but especially for White women and girls. This is no country for weak men. It demands clear-eyed, cold-hearted protectors committed to a particularly pessimistic realpolitik. Kill or be killed. Control or be controlled. Protect Whiteness and White womanhood against all threats foreign and domestic.

The most interesting thing about The Searchers doesn’t have anything to do with its protagonist. Instead, it’s the film’s depiction of every White male character who isn’t John Wayne. Over the course of its runtime, the audience is presented with a veritable rogues gallery of ineffective protectors— men who are brought down either by their self-serving bluster, their comedic softness (both mental and physical) or (most notably) their over-sentimentality. Much more than the Comanches, weak White men are the movie’s true villains. If they had done their jobs (which is to say, if they had been God Damned Real Men), the Edwards family wouldn’t have needed the protective fury of their most malevolent relative.

When I first announced that I would be covering The Searchers as part of this movie series, multiple people asked if I had read Jesus and John Wayne, Kristin Kobes du Mez’s history of 20th and 21st Century American White Evangelicalism. I get why. Du Mez’s is a comprehensive analysis of how conservative Christians found themselves in thrall to myths about a dangerous, sinful world where White families required the protection of strong, violent White men. It’s an important story, and Du Mez tells it well.

My fear about the way books like Jesus and John Wayne are popularly metabolized, though, is that the majority of readers can let themselves off the hook. It’s easy to devour a few hundred pages about James Dobson and Phyllis Schafley and Tim LaHaye and— if you’re not a White Evangelical— cloak yourself in a smug blanket of comparative superiority.

If only the twin myth-making machine of patriarchy and White supremacy was that limited.

We live in a world where White people on both sides of the political spectrum have learned to mouth at least perfunctory apologies for the various sins of Westward expansion. Whether those apologies take the form of the now-totemic liberal land acknowledgment or the popular White claim (particularly prevalent in conservative White communities) to have “some Cherokee blood ourselves,” 21st Century White Americans are much more likely to cast Indigenous Americans off to the new reservations of pity and tokenization than the old ones of fear and villainization.

That doesn't mean that the myth of a dangerous, sinister West— a place where White women and children need to be protected by any means necessary— has disappeared. Like all our best myths, it’s just evolved.

In just the last week, the New York Times— a newspaper headquartered nearly 3000 miles from downtown Portland, Oregon— has published three different articles or editorials about that city’s twin homelessness and fentanyl crises. These articles have focused not on issues of affordability, nor the corporations that created America’s opioid crisis, nor whether the investments in rehabilitation and housing services promised by Oregon’s Ballot Measure 110 have actually come to fruition. Instead, they all tell the same story: how a liberal municipality dug its own grave by being too permissive towards their unhoused and/or drug-addicted neighbors.

Portland is taking its current turn in the spotlight, but virtually every major Western city has seen its share of both local and national concern trolling in regards to homeless encampments and “chaos on the streets.” Similar articles have been written about Denver, Seattle, Phoenix, Los Angeles and San Francisco. Especially San Francisco. My goodness. Have you heard about that place? It is in chaos. It is a failed state and an American dystopia. It is in a doom loop.

There are stories like this about other cities, of course. If the breathless reports are to believed, the unhoused and fentanyl addicted are just as likely to come for your children in Philadelphia as they are in Oakland. There are dangers around every urban American corner, don’t you know. Did you catch the latest Fox News report from Chicago? There are Black people there. Black people with guns. Try that in a small town.

But there is something distinct about the way America discusses the apparent terror of daily life in its largest Western outposts. The point of dozens of dispatches from the “war zones” on the Pacific Coast isn’t just to stoke fears of crime. It’s to harangue weak-kneed liberals for being too big hearted and idealistic. As it is in Portland, so it is in San Francisco and Los Angeles. The problem isn’t rampant income inequality or the Sacklers or our societal unwillingness to provide people without homes with, you know, homes. It’s that Chesa Boudin made the cops too sad to arrest anybody in San Francisco. It’s that those bleeding hearts in Portland are "only using carrots, and not sticks.” It’s that back in the summer of 2020, those crazies up in Seattle made that one neighborhood into a temporary autonomous zone and kicked out the police.

The point of all the “[Insert name of city] is a war zone” pieces is that they all come with a pre-ordained remedy: more militarized law enforcement, more arrests, more John Waynes. Caring about our neighbors would be fine and good if the world wasn’t a frightening place. But it is. Terribly so. And the only solution is that we turn to the toughest, gruffest and most hateful amongst us to do our dirty work. It is always “Law And Order” time in the West. That’s how it was in the days of the cowboys. That’s how it was in the 1950s when The Duke owned the box office. That’s how it was when Nixon rose from the West in the 1968 and Reagan followed suit in 1980. And, we are told, that’s how it still is today. That’s the story we are doomed repeat again and again until it literally kills us.

On June 25th, in the booming (and increasingly unaffordable) Northwest Montana city of Kalispell, Montana, an unhoused man named Scott Bryan approached two teenagers at a gas station. Bryan had only been recently been kicked out of his unit in a low income housing complex. According to friends, he was evicted for inviting other unhoused people to stay with him. He was a kind hearted guy, but when he asked for help, it cost him his life. The two teens beat Bryan to death, literally crushing his skull. In a single bloody moment, the old Western myth was brought to its logical conclusion. Bryan was homeless, and we’ve all been told— not just by Fox News, but by our nation’s paper of record— that kindness towards the homeless is dangerous. Enter two teenage John Waynes, self-styled vigilantes in a pickup truck.

There’s a paradox to the Western myth. It is the land of endless opportunity, but also the land where polite civilization disappears. White America was and is entitled to its riches, but we can only truly live free if our women and girls are protected. It isn’t a land for the heroes we want, but for the grumbling but pragmatic misanthropes we deserve.

Joan Didion, native daughter of post-war Sacramento, famously wrote about how she wished, in “the part of my heart where the artificial rain forever falls,” that John Wayne would sweep her off her feet and take her to “the bend in the river where the cottonwoods grow.” That bend in the river is a myth too, of course. We have thousands of years of history to show that when we seek protection through domination— more Whiteness, more patriarchy, more separation from one another— we lose. But just contrast that sentence with the one preceding it. Whiteness/patriarchy/separation: those are all dry, intellectual concepts. What chance do they have against the part of our hearts where the artificial rain forever falls?

Regardless of how much it fascinates auteur directors and erstwhile newsletter writers, America does not currently have The Searchers fever. Instead, 2023 has been the summer of Barbenheimer, a time for two very different movies that will— thanks to the randomness of release calendars— be forever linked in the popular imagination. And while neither film is perfect (they could both do well to wrestle with race much more than they do), it’s not surprising why they’ve both evoked such collective wonder.

While these two films are incredibly different (for example: one has multiple female characters who exist for reasons other than to inspire and/or scold the male characters, whereas the other is about J. Robert Oppenheimer), there is unintentional connective tissue. The week they came out I joked that— between Barbieland (which, with its mountains, beach and desert is very clearly California-adjacent) and Los Alamos, New Mexico— both films are about how cool it is to hang out with your best friends in hard-to-find Western outposts.

It was a dumb joke, but it’s also not totally wrong. For me, the most fascinating part of both movies is their shared longing for a better world than the one we’ve built. In Barbie, of course, that world is an imagined multi-racial matriarchy free from systems of domination. In Oppenheimer, it’s the utopian version of the 20th Century that the film’s real-life Berkeley intellectuals— theoretical physicists, psychologists and philosophers, all with far-left politics— hoped they would help build.

The gruff, cynical, John Wayne take on both films is that our world has no place for those dreams. Barbieland is clearly a fantasy, and the patriarchy very much isn’t. Meanwhile, the leftist scientists were all wrong: Franco defeated the anarchists in Spain, Stalin killed the dream of the workers paradise, and the Berkeley dreamers were only of interest to the U.S. Government for as long as it took them to build a world-destroying death machine.

The cynics aren’t totally wrong. Yes, the world is full of dangers. Dangers of our creation. Dangers constituted and reconstituted by systems of domination and separation. Dangers borne from our addiction to old myths.

But there is something lovely about our longing for something better. There is a lesson in our dreaming, our yearning, our innate collective knowledge that we deserve a better world than this. That longing is not imaginary. And it too lives in the honest, romantic parts of our heart, the part where the artificial rain falls forever. Again, it’s not surprising that millions of movie-goers have flocked this summer to films that depict that longing so vividly. We are told that we are cold and heartless and a danger to one another, but if that is the case, then how do we explain the sheer volume of our capacity for love and imagination.

There is a lot riding on the myth of fear and danger, the myth of our limited capacity to care for one another, the myth that human beings and not systems are the problem. But look where that myth has gotten us. It’s delivered us a million miles away from the world we actually want and deserve.

The John Waynes of the world can’t deliver us to that bend in the river where the cottonwoods grow. They can’t deliver us anywhere, as it turns out. That deliverance is on us, together. And we can’t go West to find it. It lives in that difficult-to-access but fully non-mythic place on the other side of our fears.

End notes:

I’ll give John Wayne this: He’s pithier than I am. His catch phrase in The Searchers is “that’ll be the day,” which does in fact sound cool. That phrase, of course, inspired a very good song by Lubbock, Texas’ own Buddy Holly. Though Holly would die too young, his song has lived forever (John Lennon’s pre-Beatles skiffle group, The Quarrymen, did a cover, as did Linda Ronstadt. More recently, Modest Mouse put out a version that sounds a lot like a Modest Mouse song— I recommend it). For “Song of The Week,” though, I went with the recording by French yé-yé legend Françoise Hardy. Why? I mean, it’s a fine version, though not particularly inventive. But this video! Why is Françoise hanging out on all these tanks? What is she trying to say? Does it have something to do with Situaitonism? Oh, to be enigmatic and French.

As always, the entire Song of the Week playlist is available on Apple Music or Spotify

An English friend of mine was absolutely besotted with The Searchers and I have done my time with the other John Wayne/John Ford myth The Quiet Man. This was another excellent essay but it definitely highlighted that the films you've covered that I've really engaged with were the ones where whiteness intersected with women (ie: GWTW, Pretty in Pink, Dirty Dancing). I don't mind a good western, though! Ballad of Buster Scruggs is one of our favs!

Kind of tangential, but I realized I’ve seen only scenes from The Searchers, in the excellent documentary, Reel Injun, about indigenous representation in Hollywood.

https://www.reelinjunthemovie.com/site/

It is one of my very favorite documentaries. I show this film in media studies classes, always watching with students and taking notes. I never tire of it, and I’m enraged again every time by the scenes in the children’s summer camp. Students always find it powerful as well.