I'm not really mad at Rennie Davis

On heroes and villains, hopelessness and projection and finally finding your way home

Notes: For the sections below about Rennie Davis, I lean heavily on Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels and Black Power by Amy Sonnie and James Tracey (folks who’ve been around for a while will recognize it as one of my most frequent recommendations) as well as Davis’ autobiography, The New Humanity: A Movement to Change The World.

Also, I speak very highly about Dear Butte, a very lovely writing residency and community project that I was very fortunate to get to be a part of this past week. Dear Butte is incredible and (a). if you’re a writer or musician, you should apply for a future cycle but much more so (b). if you’re somebody who likes supporting good community initiatives, please consider tossing them a few bucks.

I don’t talk about my own political hopelessness here much, not because I never feel hopeless, but because I think there’s value in creating and maintaining a space that doesn’t just point out that the bad things we’re seeing in the world are, in fact, bad.

But of course I feel politically hopeless! Quite frequently, actually. Sometimes I feel hopeless because of a big, awful news event, but more frequently it’s because of an unshakable fear that so much of what myself or other people who crave a kinder, better world are doing (yelling at each other, preening and congratulating ourselves on the correctness of our opinions, devoting all of our energy and effort for social change into paid nonprofit employment and not enough in our communities) isn’t helping matters very much.

I’ve got a whole truckload of dumb patterns I fall into when I feel politically hopeless. I spend more rather than less time on social media. I spend more rather than less time seeking confirmation that whatever rut I’m in is, indeed, rut-worthy. I spend more rather than less time refreshing my inbox hoping for… who knows exactly. Something that might validate my ego? A breaking news alert that the world suddenly decided to stop being full of pain and instead is full of love and community-building now? A sign from God? It isn’t clear.

Whatever else I do, though, I can tell that I’m really spiraling if I start thinking about Rennie Davis again.

There is no good reason for me to ever think about Rennie Davis. I have no personal connection to him whatsoever. He exists to me solely through half-read books about the ‘60s and crackly Youtube clips and a 70% fictional Aaron Sorkin movie that doesn’t seem at all aware that it isn’t telling the truth. He’s not one of the most prominent names from that decade— it would be one thing, I suppose, if I had a weird para-social relationship with Angela Davis or the ghost of Bobby Kennedy— but Davis wasn’t even one of the four most famous Chicago Eight defendants. He doesn’t deserve any weird, judgmental fixation from somebody who could have been his kid.

None of this is actually about him, of course. But still, listen to this story.

Rennie Davis grew up in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. He went to college at Oberlin and soon found himself at the center of a fledgling Students For a Democratic Society, the central organizing body for the young White left in the early 1960s.

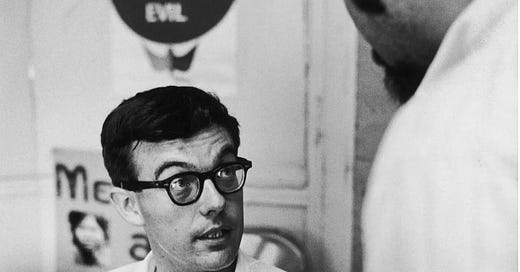

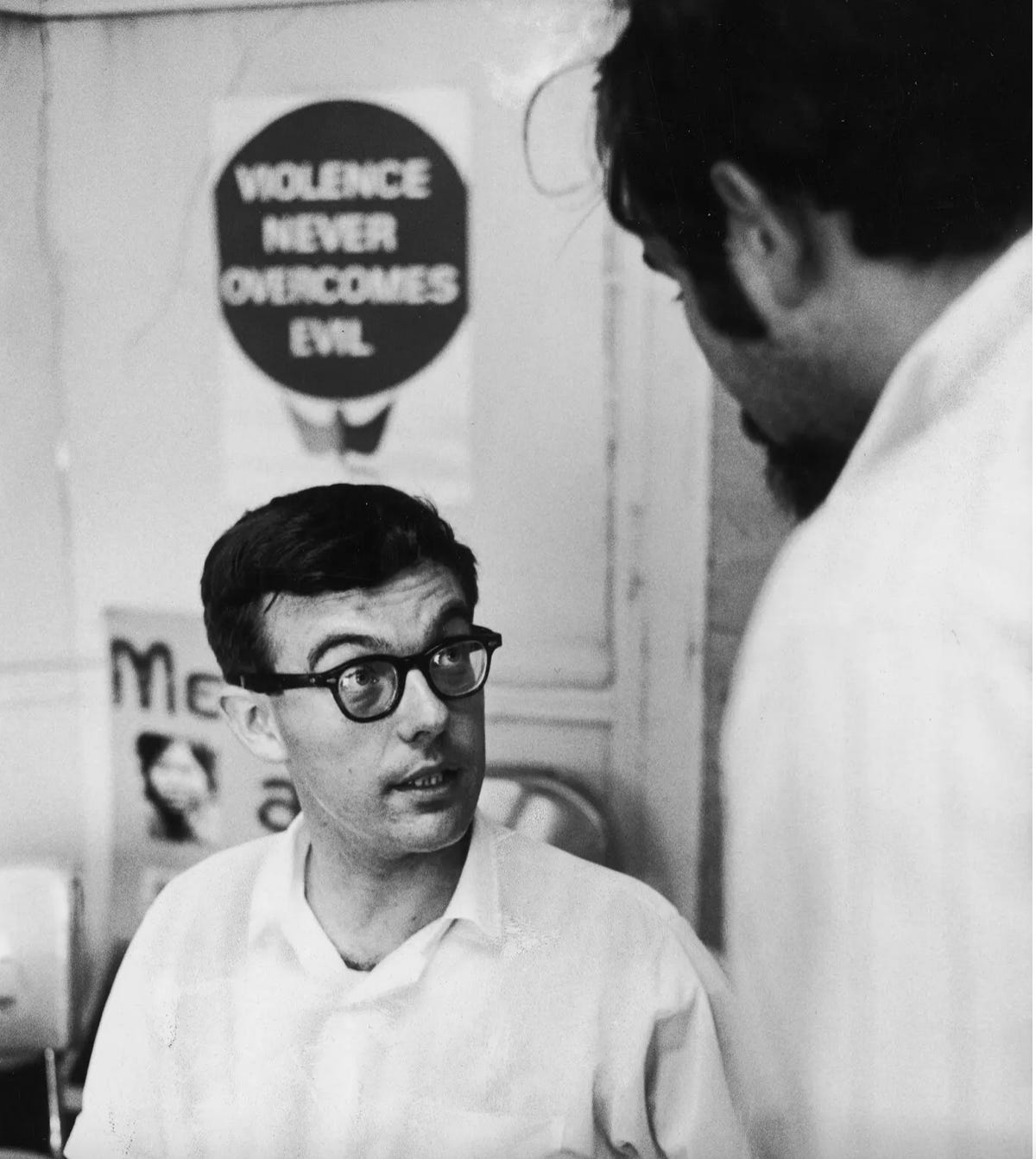

Early on in its history, SDS had designs on expanding its base beyond its natural constituency with middle class White college kids. Their most ambitious attempt to build a cross-racial, cross-class movement for liberation was called ERAP, the Economics Research and Action Program. Davis coordinated it. ERAP’s basic idea was an echo to encourage undergrad radicals to leave their campuses and instead live and organize in poor, mostly White neighborhoods in Northern cities. Many of those attempts failed, for reasons you could probably guess. But not the Chicago project. Led by Davis himself, ERAP organizers moved into crowded railroad apartments in that city’s Uptown neighborhood (home to the country’s largest population of poor Appalachian migrants at the time). From the start, Davis was a preternaturally skilled organizer, able to build relationships rooted in genuine curiosity and respect. He didn’t lead by charisma, but instead encouraged and cultivated the leadership of neighborhood residents.

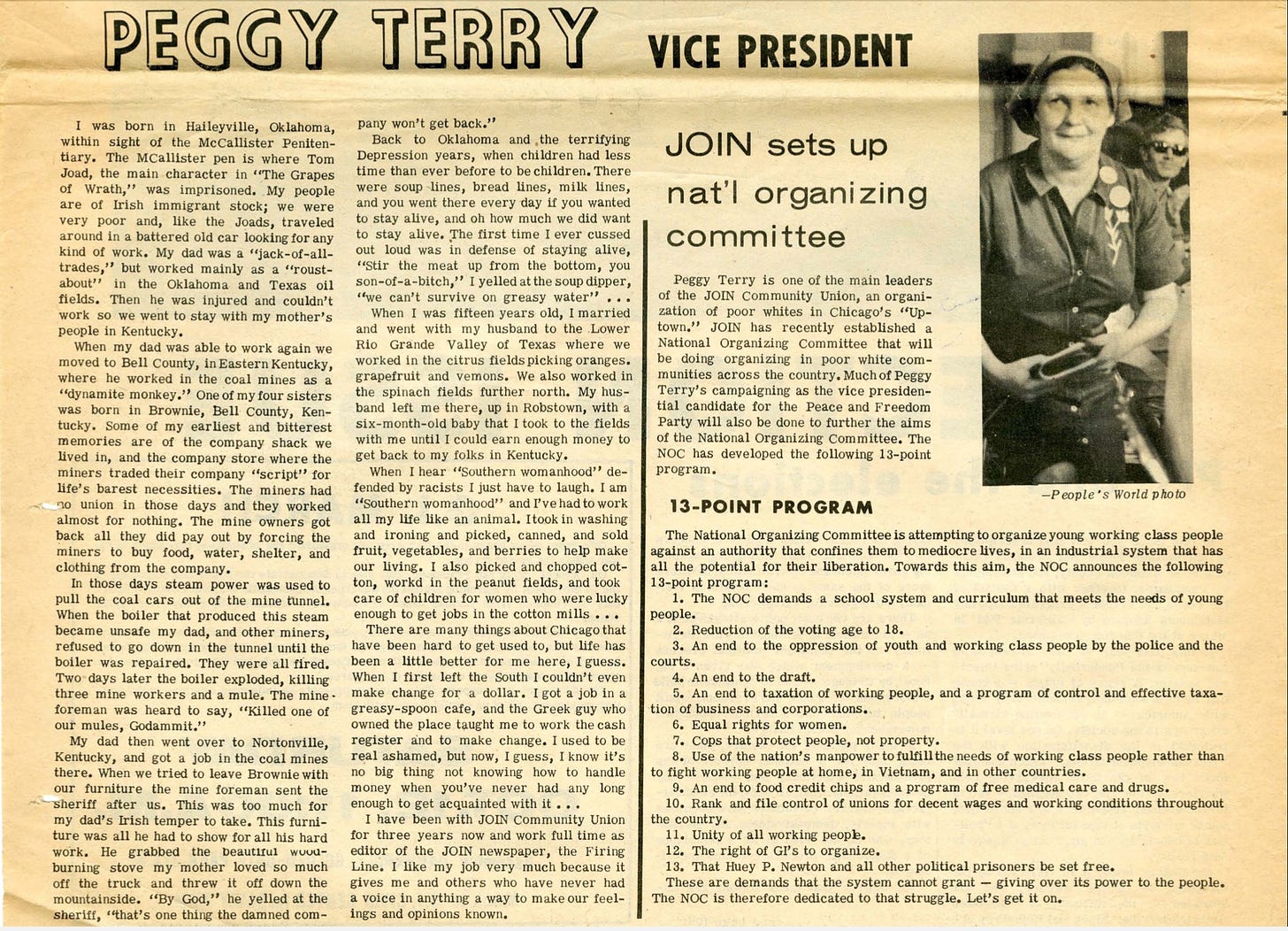

One of the initially skeptical Uptown residents whom Rennie Davis helped organize was Peggy Terry, an Okie whose life had criss-crossed the parts of the country where jobs might fleetingly be available for poor folks. Terry, who would end up leading Uptown’s JOIN Community Union and even ran as the Peace and Freedom Party’s candidate for U.S. Vice President (on a ticket with Eldridge Cleaver), never thought of herself as a leader or an organizer before Davis drove her to a large rally on the South side and encouraged her to speak. Over the years, the organizations she and other Appalachian organizers led would help Uptown residents win victories for housing and education, serve as one of the key prongs of the original Rainbow Coalition with the Black Panthers and the Young Lords, and eventually provide key infrastructure to elect the reformer Harold Washington as Chicago’s first Black mayor.

Uptown Chicago wasn’t the only neighborhood in the country (or that city, of course) with a strong tradition of local community organizing, but it was one of the few places in the 1960s that proved that working class Whites weren’t just sitting ducks to be scooped up by the George Wallaces and the KKKs of the world into the worst kind of reactionary politics. JOIN not only built trust and won victories for neighborhood residents but also hosted community school sessions to combat biases against their Black and Brown neighbors. As a result, the hillbillies of Uptown consistently shocked not just naysayers but even the most optimistic of civil rights activists by consistently showing up in solidarity for Black and Brown-led freedom struggles. Davis himself remembers Martin Luther King Jr.’s disbelief that a freedom movement could be brewing amongst poor Whites.

It was during this time that I first met Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He came to the city to organize open housing marches in the white working area of Cicero. He knew he would be facing hostility from the segregated community but didn’t know we could bring white welfare mothers from Alabama and slum tenants from Mississippi to join him in Cicero. I decided to share the news with Dr. King at a South Side church’s. As we stood side by side at two urinals, he seemed genuinely perplexed …White farmers and urban gang high school “hillbilly” dropouts were going to join his Chicago march against racially segregated housing? I was kidding, right? As we spoke and laughed in the men’s room, I assured him he would definitely get his hair blown back by the good people of Uptown. When hateful words and bricks went flying… in Cicero, our Uptown community did not disappoint my men’s room bragging either.

Davis was quickly pulled away from Uptown, but that’s understandable. He was SDS’s best organizer, and after a year-or-so of ERAP, SDS shifted its focus from neighborhood-based organizing to mass mobilization against the Vietnam War. Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, Davis organized some of the largest and most effective anti-war demonstrations in United States history. Along with so many White male leaders of the New Left, however, he also became more and more enamored with people like himself— young, freaky, individualistic hippies— as a uniquely benighted vanguard. He got a bit high on his own supply. He and the other Chicago Eight defendants delighted in their ability to put the ridiculousness and stodginess of the system itself on trial through guerrilla theater and public mockery, and while doing so had its advantages (the system was and is, in fact, quite ridiculous), it also came at great risk. By the end of the 1960s, Davis and other activists were more interested in drawing clear lines in the sand than welcoming in Americans who might see themselves more as squares then freaks.

There would be no return to Uptown, either physically or spiritually.

Instead, understandably jaded by the endless war and tragedy after tragedy, Rennie Davis chose one of the most cliched white radical paths possible. He gave up politics to search for individual enlightenment. He went to India to find a guru, and came back singing the praises of a teenager named Maharaj Ji who claimed to be a literal deity on Earth. Ji’s Divine Light Mission was very likely a cult, and Davis was a true believer. He put on a big to-do for Ji in 1973— he billed it as the most important event in history. They held it at the Astrodome and promised that collectively, Ji’s followers would levitate the dome and and a new era of human consciousness would be unleashed. The Astrodome did not, in fact, levitate. It would be the last major event that the New Left’s one-time best organizer would ever coordinate.

This is all tremendously unfair and judgemental of me, of course, but I already told you that none of this is about Rennie Davis.

He doesn’t owe me anything, by the way. He was one hell of an organizer. He did more for the cause of justice for all than I ever will. The fact that he didn’t organize his entire life in Uptown isn’t a failing; had he stayed longer, he would have been tempted to be that neighborhood’s savior rather than to turn the keys over to folks like Peggy Terry. He burned out because he was a twenty-something kid trying to take on one of the most heinous wars in American history. He saw his friends and heroes die. He saw the limits of selfishness and self-centeredness. Of course all of that made him turn inward!

What right do I have to tell his story as a cautionary tale? Why am I penalizing him for the fact that, for a short period of time, he did something— quite successfully, actually— that so many other self-styled progressives, radicals and social change agents don’t do?

Well, I mean, that’s the answer isn’t it? I want so badly to believe that there is a space beyond our current politics— a place where those of us who crave justice (particularly those of us who live relatively cloistered professional managerial middle class liberal lives) stop performing for each other and welcome all of our neighbors into a more generous, caring political vision. Rennie Davis’ Uptown years— which I’m sure were much more complicated in practice than the story I tell myself— are important to me because they offer a glimpse where all of that is actually possible. Of course I want to preserve them in ember! Of course I want to imagine that SDS never scrapped ERAP and generations of young White middle class radicals stopped talking about working class people as abstract objects and actually learned the hard work of solidarity and interconnectedness! Of course I wish that people like me didn’t all move from the small towns where they grew up to the same handful of large metro areas! Of course I wish we didn't all feel consigned to the limits of political and demographic maps, but instead that we actually believed we could change hearts and minds!

But it’s not just that. Because I could want all those things and still not fixate on the story of a single Heroic White Guy from the past who let me down personally by not delivering us all to the promised land. I don’t have to be this weird about it. And sure, part of all of this is that I am a White Guy who can get caught up in my own self-aggrandizing hero’s story. But I also think there’s another element here that’s more universal— I feel small and scared and hypocritical because the world feels like it deserves a certain level of political engagement and effort, and I feel so ill-equipped to play my part. I’m not mad at Rennie Davis. I’m feeling small and powerless and eager for somewhere to project all of that energy.

Sometimes I feel hopeless but sometimes I don’t. I didn’t feel hopeless a week ago. I was in Butte, Montana, a much-misunderstood old mining city which, at its best, has always been an organizers’ town. In its heyday, when the Richest Hill On Earth was pumping out a good percentage of the world’s copper, Butte was considered the nation’s “Gibraltar of Unionism.” Some of the most legendary organizers in American history— Mother Jones, Emma Goldman, Big Bill Haywood— spent significant time in town. Butte’s a fraction of its peak size these days. There’s only one mine still open. But it’s still an organizing town if you know where to look.

I was in Butte for a writing residency. The deal is, you get use of a lovely old miner’s cottage at the top of the hill for 10 days or so in exchange for doing an interview on the community radio station and hosting a community event. I was fortunate to have a really good crowd on hand for the front-yard workshop I gave last Wednesday— intergenerational; cross-class, not politically monolithic. They didn’t come out because the weather was perfect (it was in the high 40s with a decent chance of rain) or because I’m a big “must see” name. They came out because they trust and respect Christy, the woman who organized it. They came out because they care about their town and they’re invested in figuring its way through some of its biggest challenges (how to love a complicated place beyond simple romanticism, how to cultivate a vibrant, creative, open-minded community without opening the floodgates to gentrification). It was really lovely and an honor to be a part of it. Neither Christy nor any of the other folks who showed up had designs to be Butte’s Shining White Knight. What they were, though, was committed. To a place. To a set of people who shared that place. To the possibility that perhaps their story was bound up in others.

I gave that workshop last Wednesday. On Thursday morning, I woke up at 5:30 AM to get on the road, back to my home in Milwaukee, back to my kids. Somewhere between the peaks of Southern Montana and the unending prairie flatness of East River South Dakota, I hit a big bout of hopelessness. It was my own fault— I was listening to audiobooks about how much of Nixon and Reagan’s rise to power could be chalked up to White working and middle class voters turned off by smug, elitist hippies like Rennie Davis. I started thinking again about history repeating itself, about what it meant if I was just one of the repeaters.

I sat with those thoughts for a while, and then I thought again about what I had seen in Butte, about how nobody who showed up that night had designs on changing the world or single-handedly shouting down empire, but that their showing up still mattered. And then I thought about Grace Lee Boggs, the legendary Detroit activist who balanced international activism and local grassroots work until the day she died (at 100!). She was smarter than I am, more enamored with her neighbors and their potential and less enamored with her own ego. She once wrote that “changes in small places affect the global system, not through incrementalism, but because every small system participates in an unbroken wholeness…. In this exquisitely connected world, it’s never a question of ‘critical mass.’ It’s always about critical connections.”

An exquisitely connected world. Critical connections, not critical mass. It’s lovely, and true, and maybe it’s just another way of spinning that same old line about how you should never doubt the small group of caring, committed citizens can change the world. But I don’t know, something about it works better for me. A big less treacly. A bit more realistic.

I thought about that Boggs quote, and then I thought about my own uniquely White guy hubris again, about the part of me that would look at a story like Rennie Davis’ and see both a failed hero and a parable for my own inevitably failed heroism. I laughed out loud at myself. You can do that when you’re alone in a car on an empty South Dakota Interstate. The story is never about who we save. It’s never about who we let down. It’s about whether we dare look a gift horse in the mouth. We are all given a set of places to live and a set of people whom we live around and a world full of isolation in pain. If that’s not an invitation I don’t know what is.

I turned off the book on tape. I stopped in Sioux Falls for the night, led a Barnraisers cohort from my hotel room and then went to a bar and talked to a couple who had both moved there from small towns. They told me that Sioux Falls actually had a pretty good sense of community, but to not write about it too much. It was already getting too expensive. I ate a late dinner at a 24 hour place full of third shift workers from the Smithfield plant- Mexican and Somali and Hmong. It was a good meal. I went to bed missing Butte. I woke up eager to get home. The hopelessness wasn’t gone, but at least I wasn’t taking it out on poor Rennie Davis any more. I had a couple of kids in Milwaukee that I missed so much it hurt. I had work to do. I had people I wanted to do it with.

Thanks for providing such an incisive and humanizing set of reflections on one of my heroes.

What a reminder and an invitation. I need a bursting heart emoji for this one!

(It also makes me think of several writer-philosophers I used to look up to who over the past several years have become ... people I wouldn't want to be anywhere near, all white men. Reading about Rennie I wonder if there's something about the frustration born of being someone who wants desperately to change the world and forgets along the way that it's about that invitation to connect and find solidarity, not about how completely people listen to or follow you.)