It is the inconvenient, annoying and scary things that will do the most good

Set an escape fire and stare down the blaze

A note: I already know of multiple people who read this newsletter who are either sick themselves with corona-like symptoms or caring for loved ones in that position. I’m sure there are many others for whom that’s the case that I don’t know about yet. I’m holding all of you in the light. Please don’t be shy to let me know how we can all help.

My first few days of quasi-quarantine have mostly been a failure. I mean, I successfully stayed home and all, but jeez I’ve been such a baby about it. I have not seized the moment. I have not been creatively present for neighbors in need. I have not written King Lear. In fact, other than being a replacement-level parent (and executing an ad-hoc birthday party for a cartoon ant—- long story there), I’ve barely done anything productive or helpful at all. This is in spite of the fact that I am self-employed and my job responsibilities primarily include “typing” and “talking to people on the phone”— it’s not like I’ve had to adjust to life outside of the quarry.

To be fair to myself, this is all very hard and weird. And though I could write for hours about all the ways the inconveniences I’ve weathered are themselves evidence of immense privilege, that doesn’t negate all the ways that even relatively-minor forms of change can feel like a gut punch. The anxiety I feel for my community, my kids, my wife, my parents and my family is real. The income I’ve lost (and will likely keep losing) is meaningful. The confusion I feel over how to (even poorly) replicate a month of lost school for my oldest is one heck of a head scratcher. The human connection I crave hasn’t been sated by an inbox that seems solely composed of corporate emails about how Qdoba or Warby Parker are solemnly responding to this moment. The events and celebrations to which I was looking forward were luxuries, sure, but that doesn’t mean my anticipation for them was a mirage (I turned 39 this week! I was supposed to celebrate at a Bucks game! And then one week later I was going to get to see two of my best friends and watch March Madness together! I am just now realizing that most of the things I look forward to are basketball-adjacent!). Plus (and this one surprised me), the muscle memory of what it’s like to be involuntarily home-bound (it’s how I spent this fall— I was sick-in-bed for multiple months and it was awful) has just generally left me an anxious mess.

None of those things are Real Problems, of course, but they’ve been annoying enough to require some getting-used-to. I imagine that a good portion of you all have been navigating that variety of annoyance (or at least I hope that’s the case… I send my love to those of you whose problems are bigger and messier right now).

As such, I’m neither haranguing myself for being an uncreative, grumpy quarantiner nor haranguing you if you too have been distracted or ornery or unproductively affixed to social media. We are rookies at all this and new things are legitimately hard, even for those of us for who the hardest things in our lives are so much lighter than the loads others have to bear.

We are all forgiven for struggling to do even slightly hard things. But that doesn’t mean that we’re off the hook for our collective need to do things that are much harder than this.

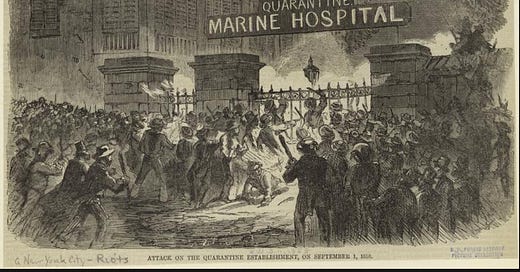

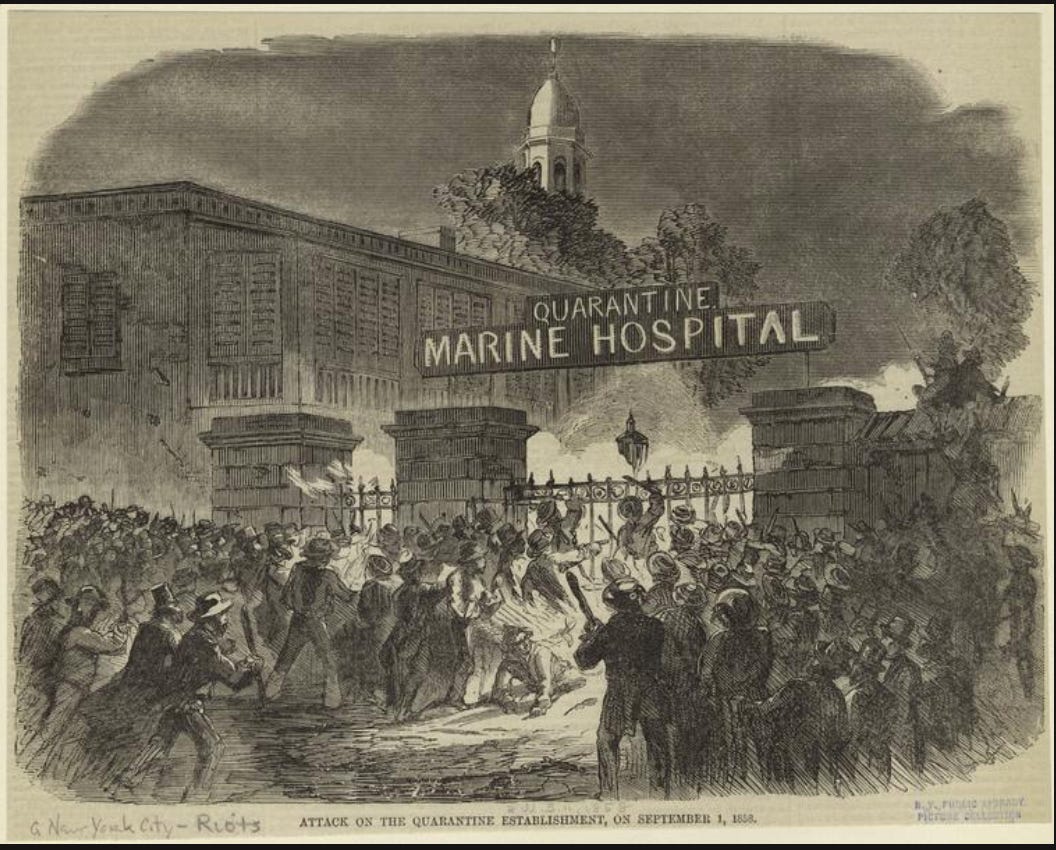

Those of you who read this newsletter regularly have had to suffer through more than your share of Montana Allegories (also known as “thinly veiled attempts to smuggle various unresolved-expat-emotions into unrelated pieces of writing”). Forgive me, if you will, one more. It’s about escape fires. If my home state had an Official Piece of Folk Wisdom this would be it.

As is true in many aspects of my life, I’m indebted here to Norman Maclean, patron saint of homesick-Montanans-transplanted-to-the-Midwest. Everything you’re about to read is a Young Men and Fire crib sheet.

Here’s what you need to know about Escape Fires. Let’s say you’re a smokejumper out on a mission. The odds are against you. The blaze you’re trying to contain is fast-moving and volatile. You can’t out-run it. Depending on the kind of brush surrounding you, very likely the safest thing to do is to Set Another Fire. Actually, your best move is even more ridiculous than that. You should Set Another Fire and Then Stand Directly Behind It. The basic principle here is that fire requires fuel, and by burning out an area between you and the bad fire, you’ll deprive the bad fire of that fuel and you’ll be (both figuratively and literally) in the clear.

The best thing about escape fires is that they work. That’s why various Indigenous Tribes have used them for generations. That’s also why, on a sweltering August day in 1949, a smokejumper crew foreman, Wagner Dodge, set an escape fire when he and his team got caught off guard by aggressive blow-up up in Mann Gulch. The fire they were trying to contain suddenly swallowed up a few thousand acres in ten minutes flat. There was no way out, so Dodge thought quickly and created one. It saved his life.

The worst thing about escape fires is that they require you to put aside every logical instinct about what a reasonable, self-interested person would do in a frightening situation. If the source of danger is fire, most people rightfully assume the solution would be Less Fire, not More Fire. I’m not trying to be cavalier or cute here; I’m merely trying to illustrate the shear irrationality of the concept with which we’re dealing. The Mann Gulch Fire wasn’t a triumph because Dodge survived. It was an immense tragedy because none of the other crew members followed his lead. He pleaded with them to join him behind the new fire line but none heeded his warning. They thought he was crazy. Thirteen men died that day.

Escape fires work, but only if you’re brave enough to use them.

“Cold Missouri Waters” (this version by Cry Cry Cry, original by James Keelaghan)

Let’s return for a second to this current frightening moment. Obviously, “learning to stay home” is degrees less difficult than “fighting fire with actual, literal fire” but the psychology that prevents the privileged among us from even doing the bare minimum of shared sacrifice isn’t very different from that which prevents larger moments of bravery. The truth is, unless I get under why I’ve been grumpy and recalcitrant to make minor changes, I’ll be less likely to do bigger, harder things that might help even more.

The list I made above, the one that chronicles why the last few days have been hard for me, was honest. It also misses the point entirely. This moment hasn’t been tough merely because we’ve had to rearrange our routines. It’s been tough because we’ve had our understanding of the world fundamentally reshaped multiple times in a few days. We went from assuming we could hand-wash our way to salvation to assuming that if we dutifully worked at home we could still eat out a little in restaurants (as a treat!) to suddenly realizing that we are weeks late in shutting down everything altogether. Every time we justified a story that let us off the hook for actually changing our lives more fundamentally, we’ve been wrong. We are rudderless right now, which makes us more likely to cling tightly to various irrationalities— be they those of the dangerous deniers (who, as Anne Helen Petersen points out, are going out to bars in an Quixotic effort to avoid accepting a reality too frightening for them to imagine) or the paranoid rugged individualists (the toilet paper hoarders, who are mirroring every lie our country has taught us about whether we are islands).

What we are discovering, more and more each day, isn’t merely that these are fraught and dangerous times, but something significantly more chilling: That we have much more power than we’d like to admit over whether our fellow human beings live or die.

99.9% of us knew next to nothing about pandemics and “curve flattening” and the tragedy of rationed ICU beds and ventilators a month ago, but here’s what we all know now: If continents worth of people did something that (depending on their privilege) fell somewhere on the range between minorly and majorly inconvenient, hundreds of thousands (and potentially millions) of lives could be saved. The problem, of course, is there have been a million good, bad and absolutely terrible reasons to drag our feet in doing so (both at the individual and collective level— very few institutions wanted to be the first out the gate telling their constituents to do something unpopular). And so here we are, having loafed through a semester of Collective Action For The Common Good 101, hoping desperately we can cram for the final.

Oh God I hope we can do this. I hope we manage both this short-term moment and that we learn the right longer-term lessons. I am hoping beyond hope that we learn that loving one another requires us to do seemingly-irrational things that we don’t want to do (like, for example, showing how much we care for humanity by staying as far away from it as possible). More profoundly, though, I hope we realize that both in moments of shared sacrifice as well as ostensibly calmer times we need to take a redistributionist and reparative approach towards those hard things. Healthy people should change their routines even more than immuno-compromised people. Wealthy people and institutions should take a financial bath so that resources can be showered towards those who can’t afford even a minor shock to their weekly finances. Those of us with safe homes to be quarantined in should fight, both today and as soon as this is over, to support the demands of people who don’t. Those of us who aren’t imprisoned should be wondering, today and all days, why any of our neighbors have to be.

The reason why escape fires are so damn irrational is that they require us to believe not merely that doing hard things could help a bit, but that doing so rigorously could have a more profound impact than we could ever imagine. The small brush fire we can start with a few matches and our bare hands is in fact extremely capable of stopping a bigger, scarier blaze in its tracks. But if we are to believe that truth, it begs a more existentially frightening question— namely, why we don’t love each other enough to take risks like that more often.

As long-time readers know, this is at least ostensibly a space for reflecting on the current state of whiteness in America (and in particular, on why we continue to drag our feet on any meaningful steps towards anti-racism). I know we’re all rightfully focused on an acute pandemic right now, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out the parallels between our response in this moment and our patterns in responding (or not responding to) more chronic, abstract pandemics.

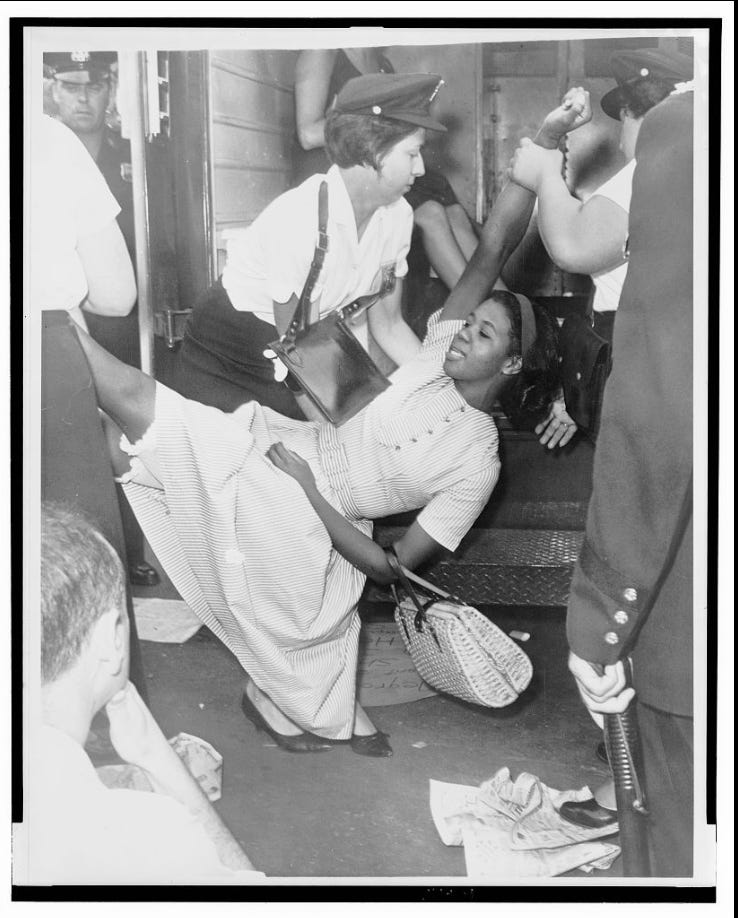

If you look back at the moments that our country has made even halting progress towards racial justice, the catalyst has always been Black, Latinx, Indigenous, Asian and Arab activists focusing their demands not on opening white hearts and minds but on unrigging power structures. It’s come from those who fought directly against white entropy, against a collective white fear of giving up power (be it the power to own human beings, the power to take land and life, the power to maintain sole control over levers of authority or the power to keep Black, Brown and Indigenous communities separate and unequally resourced). The risks they personally took in their activism (putting bodies and reputation and livelihood on the line) were audacious, mirroring the stakes of what they were asking. And in the extremely limited moments when white people stood up meaningfully next to them, they too took on some of those risks (the risks of being arrested or killed for having one’s house on the underground railroad, the risk of the billy club as you got off the Freedom Ride bus, the risk of being kicked out from the protective collective blanket of white supremacy).

My fear, based on a number of years doing equity work, though, is that too often we’re stuck at the “hand washing” level of pandemic response. Contemporary diversity, equity and inclusion work focuses disproportionally on asking individuals to reflect and journal their way to allyship. We talk a lot about “implicit bias” and “unlearning white supremacy.” These are necessary but woefully insufficient in the face of a crisis. They focus on racism as something to be individually cleansed through thoughtful, furrowed-brow meditation. What this approach leaves behind, however, is the question of what white people, both individually and collectively, will have to be willing to give up or do differently if we actually want equity. It lets us off the hook as to where we buy our house, where we send our kids to school, how much wealth we get to hoard generationally or whether we ever have to question the carefully curated academic and professional paths that cushion every step of our development.

We are learning right now, in real time, that actually caring for our community requires not merely empathy, not merely encouraging rhetoric, not merely reflection, but a tangible willingness to give up, to do differently, to take actions that you deem inconvenient, scary or onerous.

Goodness I’m rooting so hard for us, both in this moment and beyond. I’m hoping not merely that as many of us as possible get through this year alive, but that the lessons we take from how we did it allow us to build something much more beautiful together.

The blaze around us has flared up far more than we can ever imagine. We have a set of powerful, life-saving choices at our collective disposal. I’m empathetic to all the ways its hard for us to make those choices, but hard as it is, it’s the only safe way out.

This week’s songs: “The Circle Game” by Buffy Sainte-Marie. “I’ll Be Here In The Morning” by Townes Van Zandt.

Photo credits here

Oh, and also. Here are four requests: (A). Support your local mutual aid efforts (here’s an example from Milwaukee). (B). Quarantine like other people’s lives depend on it. (C). Be kind to yourself and others. (D). Let me know if I can help you in any way, even if it’s just to talk (I’m garrettbucks@gmail.com and I really mean it).