It's easy to critique The Help, but why do we keep trying to relive its plot?

A timeless story of racism, the magical power of Emma Stone's typewriter... and toilets.

Notes: Today’s issue is dedicated to Ida B. Wells and Assata Shakur, both of whom were born today and both of whom pushed our understanding of what a world beyond injustice truly looks like. My donation this week is another in a line of incredible organizations I’ve learned about thanks to participants in my organizing cohorts. This time around its Black Love Resists in the Rust from Buffalo, NY.

Welcome! This is the first in an occasional White Savior Movie Series. I say “occasional” in order to give myself as much of an out as possible in terms of how frequently I write them or how many installments there might be. Installment two might come next week or it might come four years from now…who knows! The idea here isn’t to simply declare whether a given white-directed movie is Bad About Race (that work has already been done). What I’m more interested in, from an organizing perspective, is wrestling with the fact that the movies in this series were/are extremely popular. If I care about moving white people (myself included) to be more useful for collective liberation, it makes sense to pay deeper attention to the culture that we create and the way that the long tail of that culture continues to influence us even when we claim it doesn’t.

Plus I thought watching movies sounded like fun and I hadn’t seen most of the popular “white savior” movies because they weren’t about Vin Diesel and the unique way that he drives cars (that is, both quickly and with a particular ferocity).

First out the gates, The Help!

When did this movie come out?

2011! A different era! We didn’t know any better!

Have others already written about how it is Bad About Race?

Yes, most notably Viola Davis, who deeply regrets appearing in it and argues accurately that it was made solely for white people to feel good about themselves. But oh goodness there have been so many good critiques of this film already, either about its centering of a white do-gooder or its reduction of Black characters to cliched tropes. While I’ll echo some of those arguments below, I try not to stop there. The more I watched, the more I realized the ways that the ubiquity of these critiques hasn’t kept contemporary anti-racist white activists from getting stuck in Help-adjacent narratives.

Who made it?

It was based on a book that I have not read by Kathryn Stockett. She’s a white woman from Mississippi. It was directed by fellow white Mississippian named Tate Taylor. As an expert on Tate Taylor’s life and career (that is to say, as somebody who literally just finished reading his Wikipedia) I can share that he also directed the James Brown biopic and lives on an antebellum plantation. I can also report that his plantation has its own separate Wikipedia page.

In unrelated news, if we take down Confederate statues, how will there be any record of the past?

Was it successful?

Oh buddy was it! It had the distinction of the most consecutive days at number one at the box office since The Sixth Sense, which is a big deal. That movie had a twist ending! This one didn’t have a twist ending, but wouldn’t it have been awesome if Bruce Willis was actually Racism the whole time?

The Help also got a bunch of Oscar nominations and Octavia Spencer came home with the Best Supporting Actress win. Good on her.

It came back into the zeitgeist more recently because it was apparently number one on Netflix after George Floyd’s murder, which rightfully made a lot of people mad.

What is the plot of the movie?

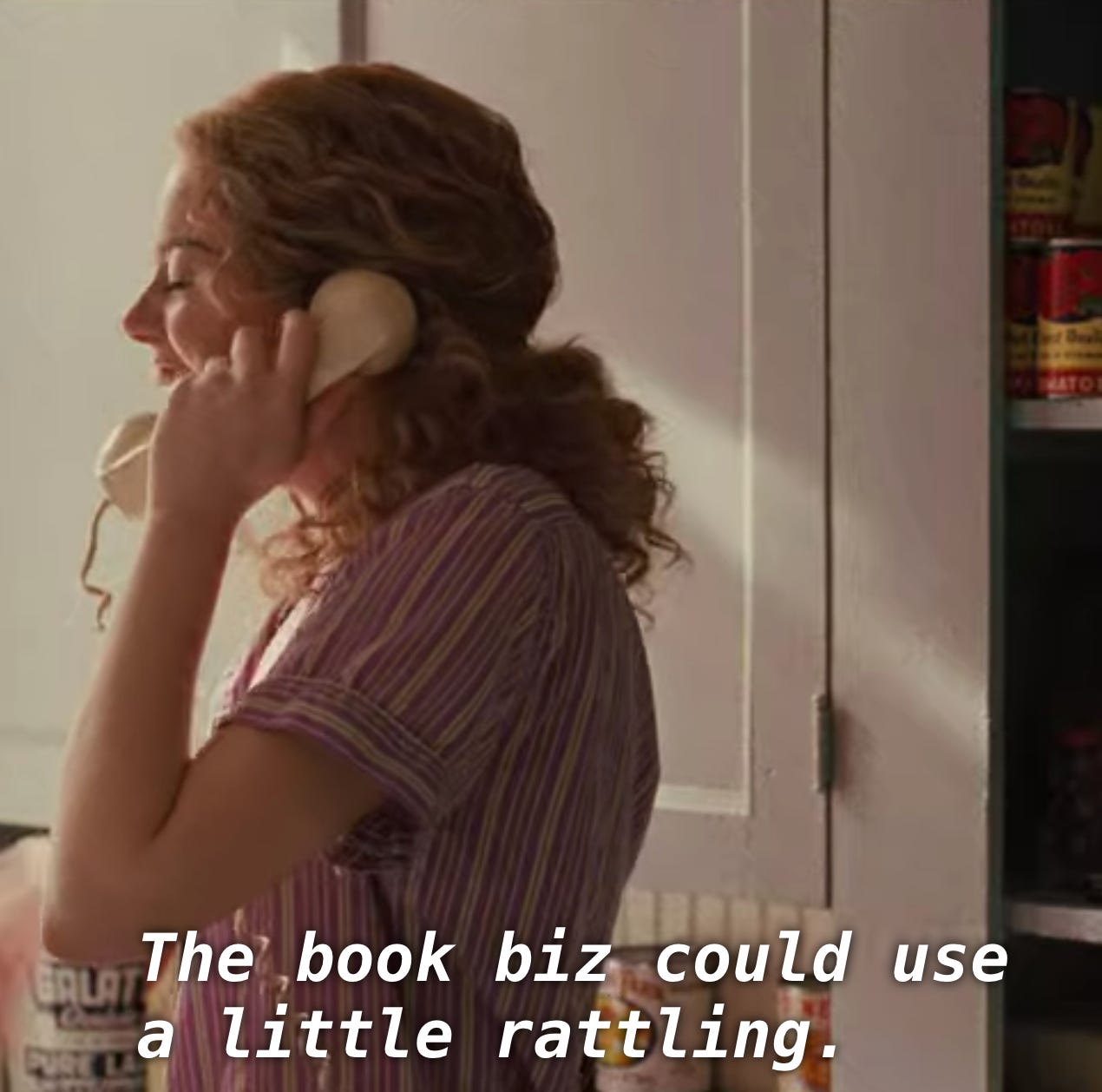

The year is 1960-something. The city of Jackson, Mississippi is home to both a bunch of wealthy white women who attend functions with one another, as well as a bunch of poor Black women who care for their children, clean their houses and prepare their food while they do so. Being a Black domestic worker in Jackson is quite bad, on account of all the racism. Fortunately, a young woman named Skeeter rolls back into town and, when she discovers that it would be a good way to get a book published, she decides to write down all the Black ladies’ stories. They’re initially skeptical but they have a couple leaders, Abileen and Minny, who get the ball rolling. A lot of other stuff happens but eventually the book is published and it Makes a Real Difference.

Is there anything particularly bonkers about the plot?

YOU ALL. Why didn’t anybody tell me that a VERY PROMINENT storyline would involve “putting poop in somebody’s chocolate pie as an act of revenge?” Isn’t that weird? Not just that there is poop in a pie to begin with, but that a major part of the plot hinges on “oh that mean lady won’t actually sue us or blow our cover because in doing so she’d have to admit that she ate the poop pie?”

If you have not watched the movie, I am not going to elaborate much more because doing so would mean I’d have to continue talking about this subject.

Oh, also there are so many toilets in this movie. Segregated household toilets. Toilet ordinances in the state legislature. Revenge toilets on lawns. Jeez.

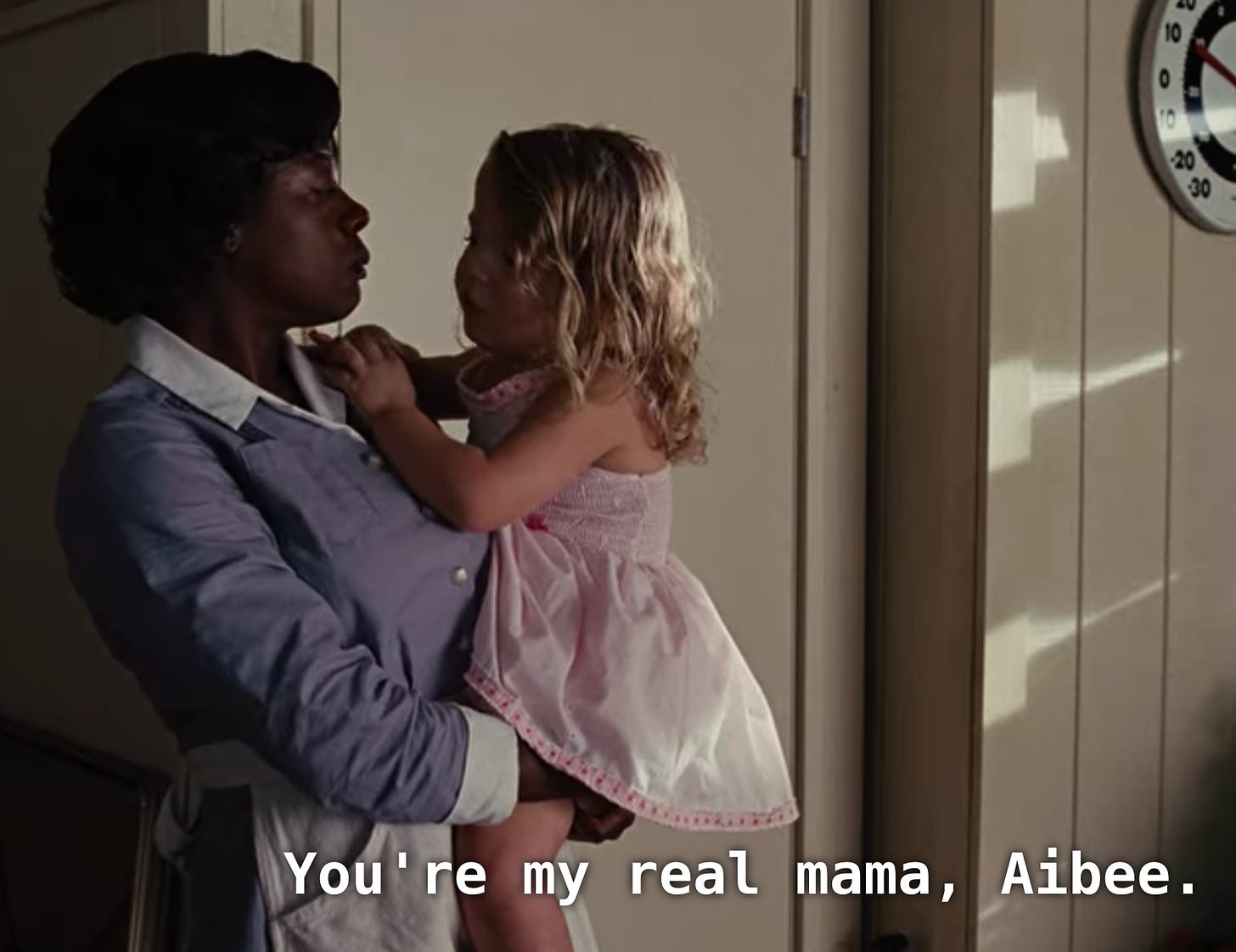

How are Black people depicted in the film?

Black women are very wise and routinely solve every problem that the small number of Good White People who interact with them have. Some of them are also very sassy! They speak colloquially. They are put upon but carry themselves with dignity. At one point, one of them gets the strength to leave her abusive husband when the white lady for whom she works makes her a particularly transcendent meal of fried chicken.

There are very few Black men in the movie. One of them is a domestic abuser. Another is a preacher, who seems nice. Another is Medgar Evers, who is murdered.

And here I was worried that this movie might reinforce stereotypes!

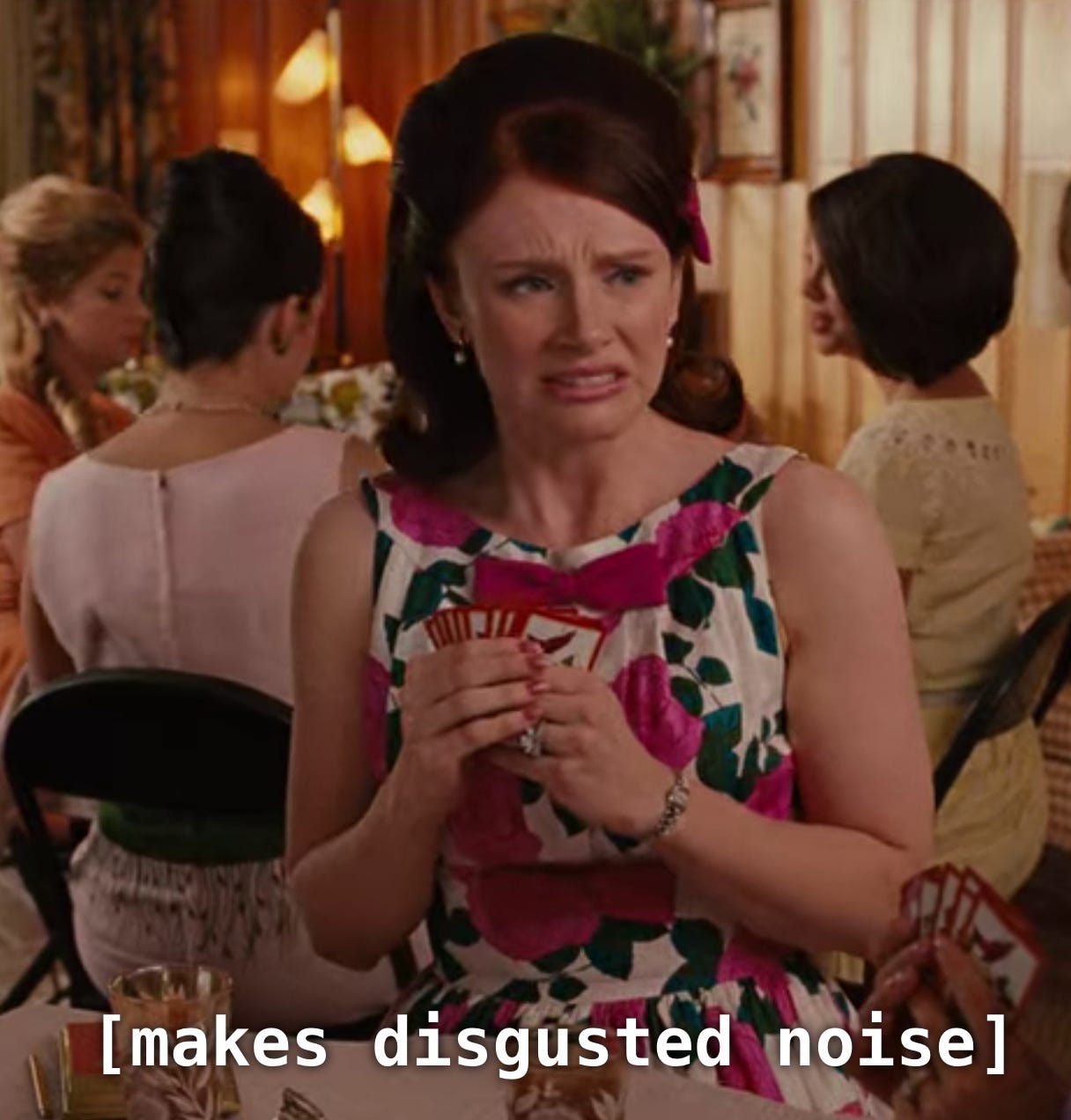

How are the bad white people depicted?

Good news! They are easy to spot, not simply because they are extremely racist and hyper-focused on installing extra bathrooms in their house (toilets! again!) but because they are terrible in every way! The Meanest White Lady is a monster to everybody— yes to Black people but also to her close friends, her mom and the Poor White Lady who is now rich because she married the Mean White Lady’s ex-boyfriend. Her sidekick, the Almost As Mean White Lady is, in addition to being racist, also the world’s worst mother. She hates and neglects her daughter because she’s chubby. Just loathsome stuff!

One can presume that their husbands are also Bad Men, but they are generally depicted as lifeless oafs being ordered around by their wives. There are a couple Bad Cops, but mostly you learn that Mississippi’s racism was caused by the cast of Mean Girls going back in time, growing up and having sour attitudes.

Oh also… only one of the Bad White People (Skeeter’s mom) ever changes her mind. The others are still Very Bad at the end of the movie, but more chagrined. Oh and one of them was made to eat a nasty pie.

How are the Good White People depicted?

Basically, you get to be a Good White Person if you already didn’t fit in with the bad white people. For instance, you can be good if you’re a social climbing poor lady from (oh jeez), Sugar Ditch, MS, but mostly because you’re naive and the other white ladies won’t hang out with you. You can also be good if you’re a slightly clumsy iconoclast who believes that writing about race can make a difference.

Actually on second thought I just realized this is a brilliant movie that makes good points. Anyways….

How do we solve racism, according to the movie?

Racism is solved if you tell the stories of Black women and embarrass the Bad White People. That’s it! Pretty simple! At the end of the movie nothing has actually changed in Jackson, but don’t tell that to any characters in the film, because they are having a grand time! The Black people are all of a sudden super happy because they have been Represented in Publishing and the bad white people look all sulky and mad because they had their spot blew up. One of the two Black Lady Leaders gets to be a writer now too, which is cool. As for Skeeter, she may have lost all her friends in Jackson but that’s OK because she gets to go to New York now and hang out with Better White People.

Oh no, this is where this piece pivots to telling us that we often fall into the same traps as the movie, right?

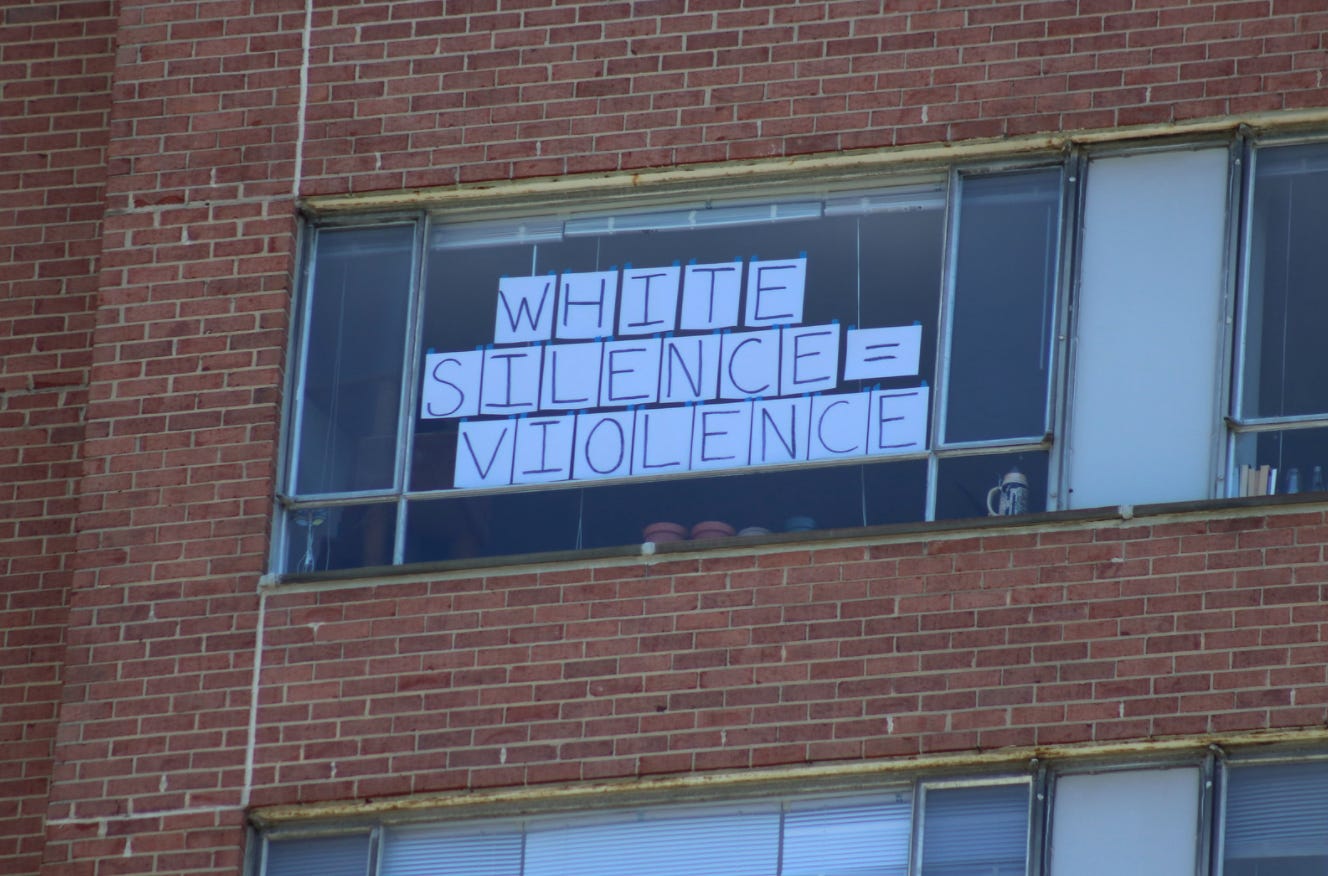

Yes! But only because it’s true! And I’m not just talking about the elements that have been frequently pulled out— the collapsing of Black identities into totems of strength and fortitude and sass, the white saviorism, the reduction of centuries of structural racism to individual prejudice. As I watched the film, what I actually couldn’t stop thinking about was this sign that’s been ubiquitous at so many protests as of late.

Elvert Barnes/Flickr (Creative Commons)

This sign isn’t wrong. White people DO have a problem with complacency, and we ARE wont to avoid criticizing systems from which we benefit. But goodness if this isn’t such a limited, non-imaginative stopping point for a collective politics of liberation. We are still basically re-telling ourselves The Help lesson— that our job is solely to find and shame the bad white people, to feed them metaphorical poop-laced pies (don’t blame me! blame that film!) and then get to ride off into the sunset with our new Black friends.

While most good conscious white people claim to know that the good/bad white people dichotomy is wrong, our actions sure as heck don’t show that we’ve internalized that lesson.

It’s why we’re obsessed with Trump and his voters being uniquely terrible stains on America’s consciousness. It’s why corporate anti-racist trainers get hired to scold the white employees of a company, leave town when nothing really changes and then come back a few years later at an increased rate. It’s why my local SURJ chapter’s only public events for multiple years in a row have been Bystander Intervention Trainings (meaning, the sole thing white people were being trained to do was how to step in when they were in public and saw other white people being racist). It’s why we yell until we’re hoarse that the Amy Coopers of the world be fired and arrested, as if doing so will set the rest of us free. It’s article after article by white people about what others are doing wrong but nothing about our own complicity (the most recent being this piece from Betsy Hodges, which effectively excoriated other white Minneapolis liberals but made no mention of the ways her actions and inactions as mayor contributed to the dynamic she is critiquing).

We may all be smart enough these days to say that The Help is bad, but goodness if we don’t keep re-writing its titular book every few days and calling it progress.

It isn’t that there aren’t any interesting or necessary stories to tell about whiteness…

One of the most persistent critiques of The Help is that it is White Centering. And absolutely, a movie by Black people about the Black domestic experience that fully decentered whiteness would have been so much more interesting and powerful. Plus, it’s not like we need more movies about white people just for the fun of it.

But, I’d argue, it’s not that there aren’t important stories to tell about whiteness, about how we got stuck here and how we might get out. To be helpful, though, those stories would be more fully about our messy dynamics with each other, not about what we do or don’t do in beknighted charitable service to Black people.

To speak directly to The Help’s subject matter, there is an absolutely fascinating story to tell about patriarchy and white femininity and the unique role that white women have been asked to play as caretakers of white supremacy. There’s a reason why a book literally about that subject (Elizabeth Gillespie Mcrae’s Mothers of Mass Resistance) has been an inspiration to many of the white women I know who are engaged in particularly reflective, transformative anti-racist organizing.

Reflecting on the rut we’re all personally stuck in isn’t about a guilt-ridden search for atonement. It is the key to empathy that makes us better organizers with other white people. It’s the tool that helps us imagine what kind of institutions we need to build so that we and other white people are less likely to fall into the traps that bedevil us. It is the difference between “White Silence is Violence” and “A Better World Is Possible.”

If I haven’t watched The Help, is it worth watching?

Sadly, no. It’s got a real all star team of actresses (Spencer! Davis! Stone! Janney! Chastain! Dallas Howard! The Queen Mary Steenburgen!) but in spite of all that talent it truly isn’t good and, again, there’s that whole business with the pie. Personally, I would have rather re-watched a more culturally powerful and transformative piece of cinema, such as the one where Vin Diesel and his friends jump their cars between two super tall towers.