It's Impossible To Learn To Plow From Reading Books

Sound and Fury. Riot Cops on Higgins. Election Night in America.

What follows is about the Presidential election, sort of.

It isn’t about your candidate-of-choice and whether my candidate-of-choice is better. It isn’t about the ways that sexism played into the viability of Warren’s campaign and how infuriating that must be for women wrestling with thousands of echoes of that same dynamic in their own life. It isn’t about whether people should be kinder online (I mean, as a general rule, yes!), nor is it about the way white voters think about and talk about Black voters and what we do or don’t understand about a complex and not-at-all-monolithic voting block. None of those are necessarily my story to tell. As for that last one, though, I highly suggest this thread by Brittany Packnett or these articles by Ashley Reece and Anne Branigan.

Instead, I’m going to tell a story I know quite well, even though I didn’t witness it first-hand. It’s about a police riot in a crunchy mountain town during the summer of 2000.

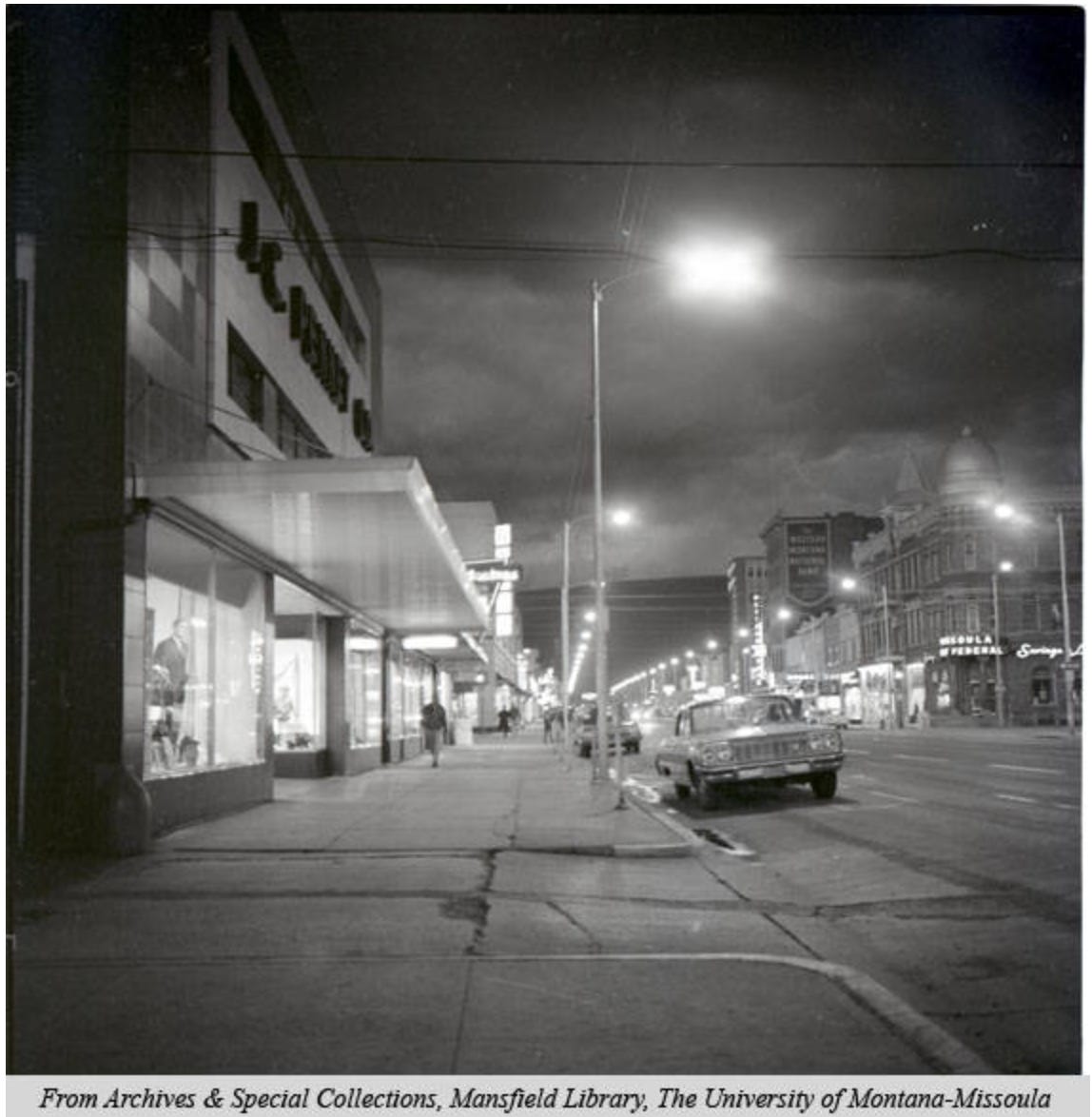

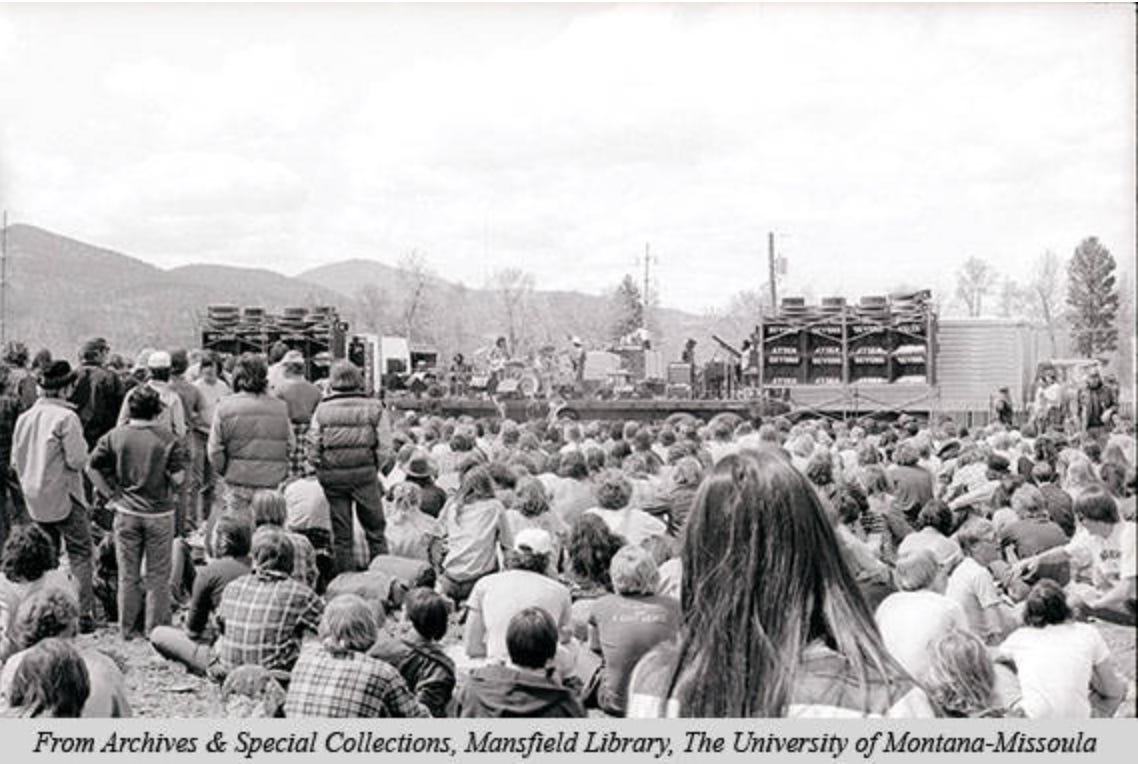

My family moved back to Montana right as I started high school. We landed in Missoula, a beautiful and blessed and thoroughly bizarre place. Missoula is Salish/Kootenai/Blackfeet/Shoshone/Pen d’Orielle land that became a mill town and then a railroad town and then a timber town and then a college town and then a place where people with big fancy East Coast jobs lived while they worked remotely. As it changed, it never fully cleaved its old skins. The Missoula I grew up in was still Salish, still railroad-drifter, still paper mill graveyard shift hesher, still acid-fried sixties drop-out, still elk-hunting RV dealership-owner, still underemployed freelance writer, still tech millionaire, still full-time short order cook/part-time punk bassist.

Most of all, though, it is a valley. It’s an ancient glacial lake, cocooned by mountains, protected from the outside world by a canyon literally called Hellgate. It is a tiny city enveloped by the world’s biggest skies. We got our first escalator my Senior year, in the Herbergers in the mall. They gave out “I rode the Herberger’s escalator!” on the first day. When you’re in Missoula, you feel simultaneously detached from the rest of the world and at the center of it. You know that what happens in your town isn’t of much concern to people in New York City or Los Angeles but that’s ok because those cities don’t matter much to whichever Creator crafted your peaks and rivers and streams with such care and attention that it is impossible to imagine them loving any other place more.

What I need you to understand is that the town where I came of age is indisputably perfect, but it’s also the kind of place that can give you a warped sense of what matters and what’s fake, where you’ll never actually know if the sky is literally, mathematically bigger or if that’s just the story we tell ourselves.

I was out of town during the summer of 2000. It was midway through college and I was working at a camp in Ohio. I came home for just a bit at the beginning though. It felt like the entire place was about to burst with the nervous/giddy/dreadful/curious feeling that, over the next few months at least, we might actually be at the center of other people’s universe, not merely our own. You see, two large convergences were coming through the valley, basically one after one another: first the Rainbow Gathering (an intergenerational encampment of hippies who gather on public land to, well, vibe out I guess) and then a Hells Angels rally.

The Rainbow Gathering went fine, by all accounts. A town that was already proportionally-heavy with white-person-dreadlocks sagged a bit more under the temporary weight of many more white-person dreadlocks. Once the Hells Angels rolled into town, though, the vibe felt different. The MPD had contracted with some outside forces to provide security. Cops from other Montana cities. Cops from Utah. One night things got a little testy- folks felt like the cops were heavy-handed around bar time. The next night, the Angels were partying out of town, but local residents held a small protest about what had gone down the previous evening. The protest mixed with summer tourist traffic and generalized downtown reveling and for reasons that were never clear the cops decided this was all a very large threat. They came in all riot-geared up. They threw elbows and tossed folks to the ground and shot off some pepper spray. It was weird and unexpected and troubling. People started chanting “The Whole World Is Watching!” The next morning, Missoula woke up and found that the AP story about the incident had been picked up by a couple big-city dailies.

In the days that followed, everybody else moved on. The whole world was, in fact, not watching. But in the valley, it felt like nothing else mattered. I may have been in Ohio the night of the riot, but for all good Missoulians, the psychic tail of the event was more important than the event itself. Over the course of the next year there were documentaries made and reports commissioned. One local paper did an entire issue with literal minute-by-minute breakdowns of what happened all night. If you had asked me at the end of the year what the top ten most important national news stories were, there’s no doubt in my mind that the police riot would have made my list.

Looking back on video footage of the night is embarrassingly underwhelming. There’s no doubt at all that police overreacted terribly, but the whole affair just looks so thoroughly tame and quaint by our contemporary standards for police riots (oh goodness that’s a depressing sentence to write). And of course, part of that is that it is impossible to watch that video in 2020, post-Ferguson, post-Baltimore and not be overwhelmed by the intense privilege embedded in what constitutes a “police riot” when the folks on the street are white. But that’s not the only thing going on here. The riot felt like the biggest thing in the world because virtually everybody who was aware of it lived together in the same isolated mountain valley. It may have been a tautology, but it was our tautology, damnit; it was big deal because it felt like a big deal to anyone who’d be likely to bring it up in conversation. It was an optical illusion-- the event’s hugeness defined by the tininess of the space onto which it was placed.

This has been a very weird Democratic primary election. Everything that we were told for many months would matter the most appears, at this point, to matter very little. Hundreds of millions of dollars and organizing hours were put into winning Iowa and New Hampshire and Nevada and South Carolina with the assumption that if you win there you win everywhere. That promise appears to have been exactly one-fourth true.

It looks like last night Joe Biden racked up victories in states he had never been to, where he had no staff. Goodness that must be so dispiriting for folks who’ve worked on rival campaigns in those states. But it also seems like that’s precisely how this half-broken mousetrap game of an electoral process is supposed to work. You jump through a series of arbitrary hoops in very specific spots- your Iowa State Fairs, your ornery New Hampshire diners, your Clyburn Fish Fries- and then at some point you all stop, a front-runner is crowned and the rest of the nation falls in line. We live in such a weird country- so obsessed with folksy hyper-localism and yet still so centrally directed.

I’m thinking today about the play-acting we so often do that we tell ourselves is us “organizing” or “doing politics.” A lot of that line of thinking is very specific to me-- this week I saw flashed before my eyes the many, many hours I claim not to have in my day that I’ve spent reading about this campaign, texting friends who agree with me, liking posts on Twitter that validate my politics-of-choice, etc. I then thought about how much any of that time has positively influenced the election specifically or our country more generally. Oh buddy, it was an ugly accounting.

This is the first branch I’m reaching at here, and man if it isn’t low-hanging: The whole “social media isn’t actually organizing” branch. The “online platforms don’t translate to real life platforms” branch. The funhouse mirror that tricks so many of us-- that since it is possible to spend an entire day watching thousands of people talk to one another that what you’re actually witnessing is millions of people working together. The intoxication with which those with virtual platforms must feel when they receive what must seem for all the world like overwhelming validation or scorn so quickly and assume that these are cities, not villages, worth of voices coalescing around them. It’s an illusion that has played out in particularly interesting ways this cycle-- in particular when the candidate who has received the most support from prominent BIPOC activists online has performed so poorly in BIPOC communities generally.

And sure, that’s on my mind. But I’m also thinking about all the real-world organizing hours that Sanders volunteers and Warren volunteers and volunteers for other candidates have made that (thus far, at least) didn’t seem to move the needle for their team as much as you might expect. In many ways, these are sophisticated campaign operations that truly have enabled hundreds of thousands of people to knock on millions of doors. That doesn’t mean that they aren’t still play-acting the work of mass politics and social change. This isn’t because what they’ve been doing isn’t real or meaningful, mind you, but it does have something to do with our relationship, as activists and change-makers, to time and community-building.

Here’s what I mean. It’s clear, in every single poll of the Democratic electorate, that this is a group that is deeply motivated by a palpable, short-term sense of fear. They are angry at a Trump Presidency and want, more than anything else, to take the quickest, most-linear path to removing him from office.

Now, is Biden doing quite well all of a sudden because his team is better organized, or “doing politics better” than other campaigns? Not at all. And while it’s totally fair to argue that his South Carolina and Super Tuesday performances were aided by big money or media bias or party corruption or what have you, he also needed to have lots of people (and lots of very different people) vote for him. The fact that he did is at least in large part because what he is offering is not challenging to the current schema of the voters to whom he is talking. They want to get Trump out and that desire is foregrounded heavily enough that everything else falls into the background. Fortunately for Biden, that’s precisely what he’s offering. When your political vision is minimally challenging to the worldview of the electorate to which you’re speaking, your work is easier.

[Note: Depending on your bias in reading this, you are likely to say either “Well, Biden’s politics may be less challenging, but they’re right for this moment! That’s not a bad thing!” or alternately “But if what you want to do is beat Trump, he’s the wrong choice..” Those are both justifiable beliefs to have, but they’re beside my current point, as are the various other side defenses or critiques of Warren and/or Sanders that are about to be inspired by my next paragraphs. Please stay with me, is what I’m saying].

In different ways, Warren and Sanders each offered a more complicated politics-- they are each asking voters who are motivated by short-term fear to vote for a longer-term hope. Warren’s pitch is about voting not just for any candidate who challenges structures of power, but voting for the first woman President to do so. Sanders’ pitch is to shake and challenge those structures even more radically, to build a set of institutions and political relationships which we’ve never had as a country.

There are really good reasons, particularly for liberal-to-left-leaning people, to be extremely excited and motivated by those pitches (or to be motivated by one of the two more than the other). Is it unfair that because what they’re asking people to imagine is bolder than Biden that it makes their work that much harder? Oh absolutely. Is it not just unfair but sexist that, for Warren, that barrier exists not simply because of an ideology she chose but a gender she didn’t? Oh goodness yes, a million times yes.

But here’s the thing. When the canvas on which to build a better world is a single election cycle, even when you’re more actively “doing politics” you’re not really building, you’re simply mobilizing. That’s true whether your candidate is moderate or a radical, whether their election would be a representational victory or not. Campaigns are short little beasts. It is the job of millions of campaign volunteers to capture the energy of people who are already 90% of the way onboard, not to ask the question “what is preventing an even broader swath of my neighbors to dream of the world I’m dreaming?”

And listen, I don’t know who will win this election— it seems like Sanders or Biden or Trump still have very real fighting chances. It also appears that, 100 years from now, when all of us have passed from this world, Tulsi will have still not suspended her campaign.

Regardless of what happens, the world which we will wake up to in June and then again in November will be one that will still be defined by limits to our collective imagination. Your preferred candidate may win, but both your’s and your neighbors’ dreams for a better future will still be much smaller than they need to be. And none of you will suddenly start to dream bigger dreams if you start waiting for the next campaign to organize again.

The work of building what has been, to this point, some of the most equitable societies in the world (the mid-century Scandinavian social democracies) did not begin when those parties won elections. They began decades previously, with folk schools and workers’ cooperatives where neighbors got in the habit of taking care of one another. Likewise, our country’s most successful social change movements never began with the flashpoint that makes the history books-- Chavez and Huerta leading the Delano growers on their first march, Parks sitting down on the bus. Those moments only came decades after the Community Service Organization had already sparked the imagination of Mexican and Filipinos in the Central Valley, after the Montgomery NAACP had run campaigns for decades after entire generations of organizers had made the trek up to the Highlander School in Tennessee.

If you woke up this morning wishing that people around you were dreaming a bigger dream, perhaps it’s a sign that you haven’t been building anything alongside them.

Perhaps that begins in your church, synagogue or mosque. Perhaps that begins in your union (or heck, perhaps that begins by building a union in a workplace that doesn’t have one). Perhaps that begins in your PTA. Perhaps that begins by organizing a neighborhood block party. I hope to keep providing examples, in this newsletter, of places to start that are specific to racial-justice organizing. But really, as long as it is productive and neighborly, anywhere you start could be pretty damn meaningful for building a more imaginative politics. I bet there’s a vacant lot not too far from your house that could use a nice garden. I bet that a bunch of your neighbors are seeing police tickets pile up for broken tail lights that other neighbors might be able to help them fix.

The reason why elections feel like the place where we do politics is because we’re used to never expanding our gaze past that particular insular valley. The thing is, there’s a world on the other side of the canyon, and once you expand your gaze, so too are you opened to a whole new world of what’s possible.

I come from a small place-- one that is so complex and messy and beautiful so as to trick its inhabitants into believing its much bigger than it is. It is a town where little things become big news, where a couple hours of tension become Chicago ‘68. I also come from a larger place that is itself still quite small. It is a country where we pretend that our chance to build a better world comes primarily every fourth year in November. It is a country where the pomp and circumstance and sound and fury of a quadrennial project tricks us into believing that’s our only source of power.

Shout-out Richard Linklater for the title. You all, it’s literally a movie set in Missoula where nothing happens. How was I not going to pick that this week?

Photo credits here

This week’s songs: “Dish Pit Warrior” by the Sputniks and “That Which Is Not Especially Fancied By One” by Humpy- the best late ‘90s Missoula punk songs about class politics and apathy, respectively.