I've been thinking about the people who set themselves on fire

Flawed offerings, a month into war

The bombs are still falling. The guns are still blazing. The tears are still flowing. It’s the tears I think about the most. Just the pure volume of them. There has been so much debate about rivers and seas, both geopolitically and rhetorically, but whenever I hear about bodies of water these days, that’s what I picture: A river of tears. A sea of tears. An ocean of tears.

I read every article I can get my hands on about Al-Shifa hospital. There isn’t enough power there. A hospital needs power to keep people alive. A hospital needs power to keep babies alive.

One of the articles about Al-Shifa was in the New York Times. Apparently there is a war of words between Hamas and the IDF about whether there is a military compound other the hospital. A proxy battle of press releases. No thank you. I just wish for an article that states “Everybody in the hospital is now safe; we have all linked hands to ensure that all of the babies will grow and thrive and live beautiful lives.”

Walls will not keep us safe. Nor will borders and checkpoints. Nor will the most powerful bombs known to humankind. Nor will warmongers who claim to be public servants.

Guns will not bring liberation. Nor will kidnappings. Nor will massacres at music festivals. Nor will warmongers who claim to be freedom fighters.

We will not build the world of our dreams by creating more victims.

I repeat all of those statements to myself, cocooned thousands of miles from machine gun fire and mortar explosions, smugly gesturing to my Ikea bookshelf full of books about nonviolent resistance, pretending as if all of those statements are self-evident to all, pausing before I answer the question about my own heritage and identity.

“Huh,” I hear the reply back.”Pretty easy for you to say, then….”

Did you hear about what happened to the children? Yes I did, and it broke my heart, or yes I did but I couldn’t metabolize the heartbreak, so I turned off my phone.

I understand why we talk about innocents in war. My heart has been crushed to dust because of non-combatant human lives reduced to collateral damage. I also know there are people— particularly men— who are uniquely culpable for others’ suffering. I still struggle, however, when we start building mental models for which human beings do or don’t deserve to die. I know where that road leads. It leads to this exact place we’re in right now. “We had to burn the village to save it.”

Here’s a belief I hold deeply: There is no taxonomy of suffering. Every family’s grief is equally debilitating. An Israeli parent’s tears are no less heart wrenching than a Palestinian family’s tears.

Here’s another one: Asymmetry is real. 3.8 billion dollars in U.S. military aid a year is real. Barricades are real. Occupation is real. Every death is a tragedy, but for years now there have been more deaths on one side of the border than the other.

I check my email. “Why do you keep calling for a ceasefire and not for a return of the hostages?” I start typing out a response, full of statements that, to me, sounded measured and logical and moral. “I very much wish that the hostages come home safely, but my government is not supporting Hamas, they are supporting the Israeli military… “ etc., etc., etc.

I pause. I realize that the question isn’t just about the hostages. The emailer is Jewish. They are asking me, in essence, if I care whether they are kidnapped or killed. I erase my previous message. I fumble through an assurance that even though they are a stranger, I care about them tremendously. I loathe anti-semitism. Of course I do. They don’t reply back. I understand.

It is a genuine blessing that people— friends and strangers alike— have reached out. It is a blessing to hear that something I wrote resonated with others. It is a different blessing when they tell me I hurt them, either through omission or commission. It is not a blessing to cause pain, of course, but it is a blessing to have a conversation I wouldn’t have had otherwise. I have learned so much in the past month.

I have heard the phrase “annihilation” more frequently in the last thirty days than at any other period in my life. “You don’t understand, my people fear annihilation...” The same phrase, in multiple conversations, uttered by Jewish and Palestinian lips alike.

My son careens up the stairs, all pale skin, flaxen hair and rounded Nordic features. He smiles and yells “Daddy, Daddy, Daddy, you have to hear what happened at school.” He looks exactly like me.

I have never feared annihilation. I have no idea what it feels like to fear annihilation.

I don’t understand. But the question remains, doesn’t it?

Don’t we want to build a world where nobody fears annihilation? And will more dead bodies get us there?

It is far easier than I would like to admit to ignore the war, to stay enveloped in my own narcissistic worries (Will everybody hate my book? Do people in my life secretly hate me? Did I sound stupid in that last conversation?).

I hug my children a dozen times a day. Not with intention and gratitude, mind you. Not with an awareness that other parents thousands of miles away can’t hug their children anymore. I hug them the way you hug your children when you never doubt that you will continue to embrace them for the rest of your life.

Sometimes I even think about dumb nonsense while I hug my children. Sometimes I check my phone as soon as the hug is over.

I say that I can’t stop thinking about the rivers of tears, but part of being human is that it often is quite easy, actually.

Another question in my inbox: “Garrett, what about all of the other wars right now? Why are you silent about Sudan or Yemen or the Congo?”

I have an answer to that question, but also… fair enough. There is always a war, and I am rarely considering that war.

The staffer answering the phones for U.S. Congresswoman Gwen Moore sounds tired today. I rush through my message, only half convinced that he’s picking up anything I’m saying. “I’dliketothanktheCongresswomanforopposingthecensureofRepresentativeTlaibandencourageheronceagaintosupportCongresswomanBush’sceasefireresolution.” No breaths. I don’t know why I’m rushing.

Before I can finish, he mumbles something about how he’ll pass my message on to the Congresswoman. It is not an inspiring moment for democracy, just as I’m sure it’s not an inspiring moment in his work day. As soon as he gets off the phone with me, he’ll answer another call. And then another. All day long. If my message is passed on to the congresswoman, it will be in the form of a tally mark.

I cycle through my hundredth doubt as to why I make these calls, but then the next day I read an article about how the staffers themselves are protesting and that’s enough to keep me dialing.

My own phone isn’t ringing as much as the one in the Congresswoman’s office, but it’s still ringing. Today it’s two more Jewish friends. One tells me that she was at a ceasefire sit-in at the capitol and she’s never felt more connected to her Judaism. It moved her to tears. The other tells me that she definitely won’t go to a protest. She doesn’t feel safe. Both of them are telling the truth.

A lot of the calls and emails this month come from Jewish friends. A smaller number come from Arab and Palestinian friends. The lopsided ratio may merely be a factor of the demographics of my social circle, but perhaps there’s feedback there for me. I think a lot about who I am and am not making feel welcome right now.

You know who hasn’t called at all? Any evangelical Christian friends, the kind whose churches account for a disproportionate amount of U.S. support for the Israeli government. The millenarian third rail in this whole affair. I have no idea if any of them are protesting or having difficult conversations in their faith communities. In the past month, plenty of people have pointed out the reality of Evangelical Christian Zionism, but I never hear anybody ask “where are the Evangelical ceasefire protests?”

These are not the only questions of the moment, but they are the ones that have been frequently posed to me this past month, particularly by Ashkenazi Jewish friends:

What does it mean to be unequivocally White?

What does it mean to be conditionally White?

What does it mean to never ever be considered White?

What does it mean to be both immensely aware of one's Whiteness and non-Whiteness at the same time?

What does it mean to be misidentified as being White?

What does all of that mean for culpability, for sympathy, for rights to reparation and restoration?

I didn’t give any answers to those questions, nor did the people posing them expect me to.

I read another article about the hospital. Israeli troops are right outside its gates. The IDF says that they are “engaged in an intense battle with Hamas” in the area surrounding the hospital. Meanwhile, the Gazan health ministry is using a very specific phrase to describe the scene inside. I’m haunted by that phrase.

I think about the hospital where my wife works, the hospital where both of my children were born, the hospital where a curious doctor once saved my life after so many specialists couldn’t figure out what was wrong with me. The phrase rattles around in my head again. I struggle to apply it to the building I know so well.

“Al-Shifa hospital is in the circle of death.”

The books on my shelf remind me that nonviolent resistance is neither passive nor ineffective. It has toppled dictators and ushered in democracy. It has engendered international sympathy for previously invisible causes. It has broken cycles of violence.

I can be awfully self-righteous about nonviolence. I don’t understand why we judge nonviolent social movements as being failures if there are any casualties, but we never judge a war by that same standard. It gets me pretty puffed up, truth be told, but I know a lot of that is just my own insecurity. It’s one of my great failings— not that I want a better world, but that I want everybody to recognize how much I uniquely care for them. I become defensive because I know that the offer I can make (“I would lay down in front of a tank if it kept you safe”) often feels insufficient when people desire so much for the world to say “I unequivocally endorse your bomb or your wall or your retaliatory killing.”

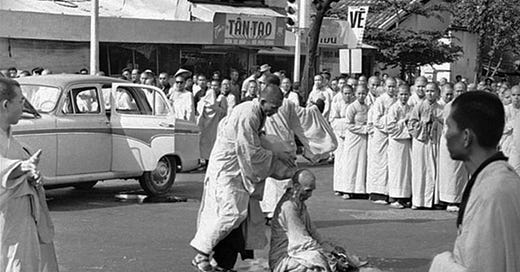

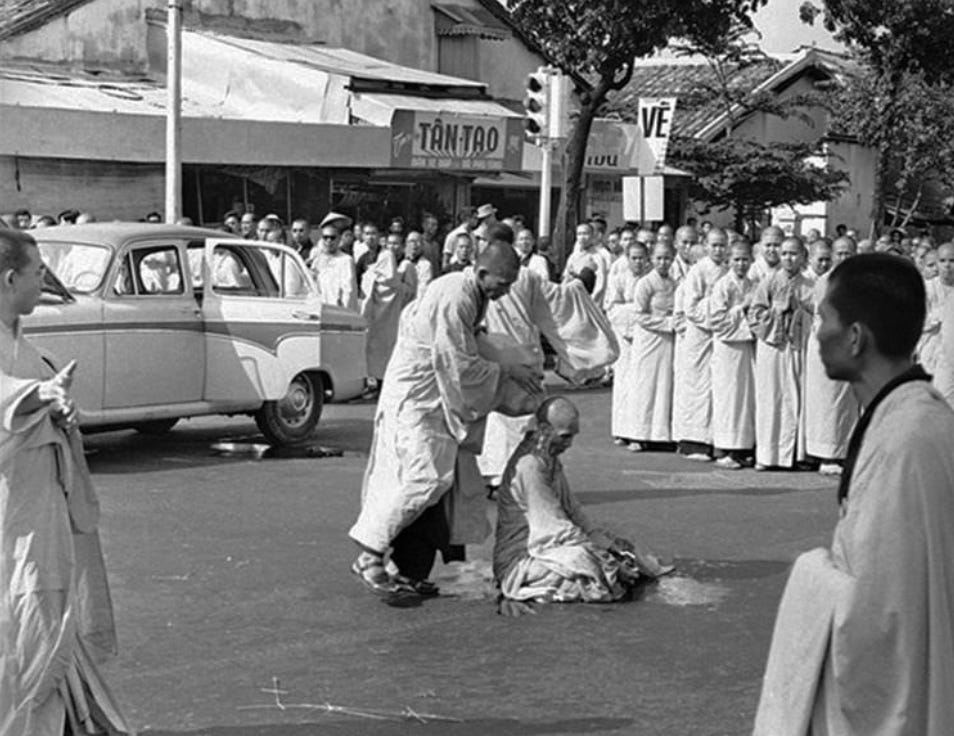

There’s an open tab on my computer. It’s been there for a few days now. An article about self-immolation. As far as methods of nonviolent resistance go, it actually has a fairly unimpressive track record. It gets a lot of attention, but it has rarely brought about nonviolent revolution.

That misses the point, though. Self-immolation is as much a spiritual as political act. By all accounts, it is excruciatingly painful. The self-immolator is more likely to die of shock— their body incapable of processing what’s happening in the moment— than from the burns themselves. And that’s the point. Burning yourself alive is supposed to be excruciating. You do it when you’re grieving— for people, for communities, for the world. You do it when you’re overwhelmed with the ugliness and suffering around you. You do it when you can no longer stand human beings’ inhumanity to each other.

I have no plans to self-immolate. That’s not why the tabs are open. It’s just that I get the impetus behind it. I understand looking out on a world of grief and cruelty and wishing that you could just suck it all up, take it all on yourself, leaving a fully healed world for everybody else.

I pick up the phone again, for any number of reasons. To call the congresswoman’s weary staffer one more time. To listen to somebody on the other line who is off to a protest. To emphasize with somebody who is angry at me for not understanding their fears of annihilation. To tell my own mother that I love her, to share a story about her beloved grandchildren.

I know that a single human being setting themselves on fire will not suck up all of the worlds’ tears. I know that the day after the sacrifice, the bombs will keep falling and the tanks will keep rolling.

But then I imagine thousands of us. Not lighting ourselves ablaze, but streaming out into the streets, again and again, day after day, all of us whisper-shouting the same promise.

“Whoever you are, if the missiles are raining down on you, I will be out here until they stop.”

A river of solidarity. A sea of solidarity. An ocean of solidarity.

Every conversation is a gift. Every shared sorrow is an offering. Every protest is a prayer.

End notes:

One of the aspects of this moment that gives me hope is how easy it is to connect to protest and action resources. I continue to lean on the resources from the U.S. Campaign for Palestinian Rights. As a Quaker, I’m biased, but I also highly recommend the work that the American Friends Service Committee is doing (when in doubt, if a war is raging, look to the AFSC). I also continue to take so much inspiration from the work of Jewish/Arab peace resistance within Israel, particularly the Standing Together movement.

Also, thank you, as always, for being here. As was probably clear from today’s essay, my life is so much richer thanks to the connections and conversations that grow out of this space. I hope the same is true for you. If you value The White Pages, know that every bit of support— be it a share, a subscription, or a pre-order of my book— helps more than I can express.

Thank you for this vulnerable articulation of your self doubts, inner critic, and inter/intrapersonal wrestlings. For being inside out with us. For taking steps and actions. For publicly growing. For showing us the power of sharing.

I generally like your writing, Garrett, but today’s piece especially resonated. It is a fair question to ask why we are upset about this war, while completely silent on so many others in Africa, so many where combatants are child soldiers, pressed into service, the stakes involve supplying American companies with materials needed to produce luxury goods. Part of being a white person with interest in dismantling white privilege means recognizing that people have every right to ask difficult questions of me, when historically they would get replies that do not satisfy, do not meet the mark.

I am a United Methodist minister and have spoken about this conflict from the pulpit a few times, the first being right after the horror Hamas inflicted just over one month ago. The rest have been in response to what people expect to hear given the flood of bigotry since then. I encouraged congregants to join me at an interfaith service of solidarity at a conservative synagogue. More than once I needed to address the fears of those with good reason to believe it would be anti-Palestinian, or pro American foreign policy, or pro the actions of the IDF. I am grateful to be in position to say something publicly, and regularly reminded that quite a lot of people are expecting to see people choose a side uncritically, giving little credence to the idea that a person could be against all of it.