Let Us Now Praise Famous Traffic Light Inventors

What, to the performatively earnest white person, is Black History Month?

I loved Black History Month growing up. My grade school took a very “multiplication tables” approach to the whole affair. It was already a short month, so it was a real race against time to squeeze as many Historic Black Names into our heads as possible before the clock hit zero and we could return our attention to the urgent work of celebrating white history year.

The best of the bunch was the one where we had a school-wide Jeopardy assembly. Representatives from every class faced off on the cafeteria stage, fake buzzers blazing, just firing off Black name after Black name. In the end, a single winner was showered with cheers from their classmates as they hoisted their official Principal-signed certificate of Black History mastery.

If you’re wondering whether I’m sitting here today, a fully middle-aged white man, bragging to you that back in third grade I unequivocally won Black history month, well yeah… that’s exactly what I’m doing. To paraphrase a certain former Presidential candidate, that precocious little white boy was me.

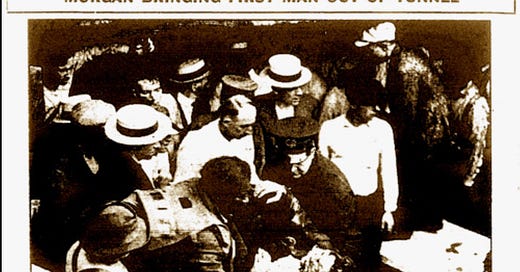

You all, I was so good at memorizing names. I was not good at long division or handwriting or God help me anything involving the gym but I’ll be damned if I couldn’t shout out “MARY MCLOUD BETHUNE” upon command. I was also aided by my school’s particular focus on Black inventors, an area I ruled at thanks to my affection for Garrett Morgan. My dude, of course, brought us both the gas mask and traffic light but more importantly had the same first name as me. Famous Black inventors! They’re just like us!

I didn’t know it at the time, but this experience, of being a white person going through a set of performative motions so as to win at Black History Month, was excellent preparation for the totality of what would later be expected of me as a white adult every February.

I still like Black History month quite a bit, though wouldn’t it be a cool contrarian take for an anti-racism newsletter to come out against the concept? [“Have you ever thought, perhaps, that ALL history matters?” the white man types, visibly pleased with his own cleverness]. That doesn’t mean, however, that the whole affair, like most of our nation’s battered, cobbled together equity infrastructure, isn’t susceptible to good earnest white people acting like the kids in the back of the choir who didn’t know any of the words but still mouthed along anyway, hoping desperately that nobody noticed.

Put differently, when it comes to Official Equity Moments, our collective white-person base-level is not to ask “So why am I doing this equity thing? And towards what end?” then it is to desperately wonder “Ok, what’s the Right Answer so that nobody gets mad at me?”

And yes, it’s extremely fun when other white people stumble face-first into the Wrong Answer [this year, America’s Most Cavernous Bookstore took the cake with its “what if we just use a different crayon for Moby Dick” move (see above) but it will never usurp the all-time king, last year’s attempt by Virginia Governor Ralph Northam to literally moonwalk his way out of a blackface scandal]. To be clear: That stuff rules and I love it. The problem is, laughing at these pratfalls have a way of taking the attention from the rest of us as we just go through the motions.

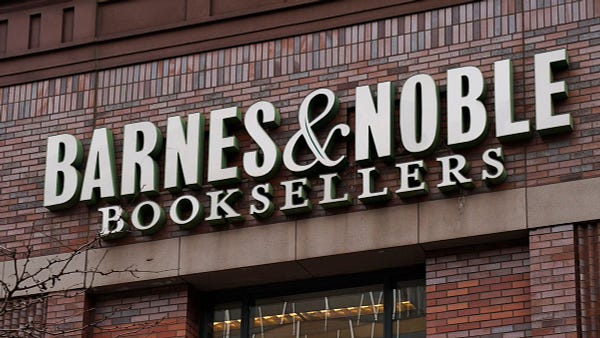

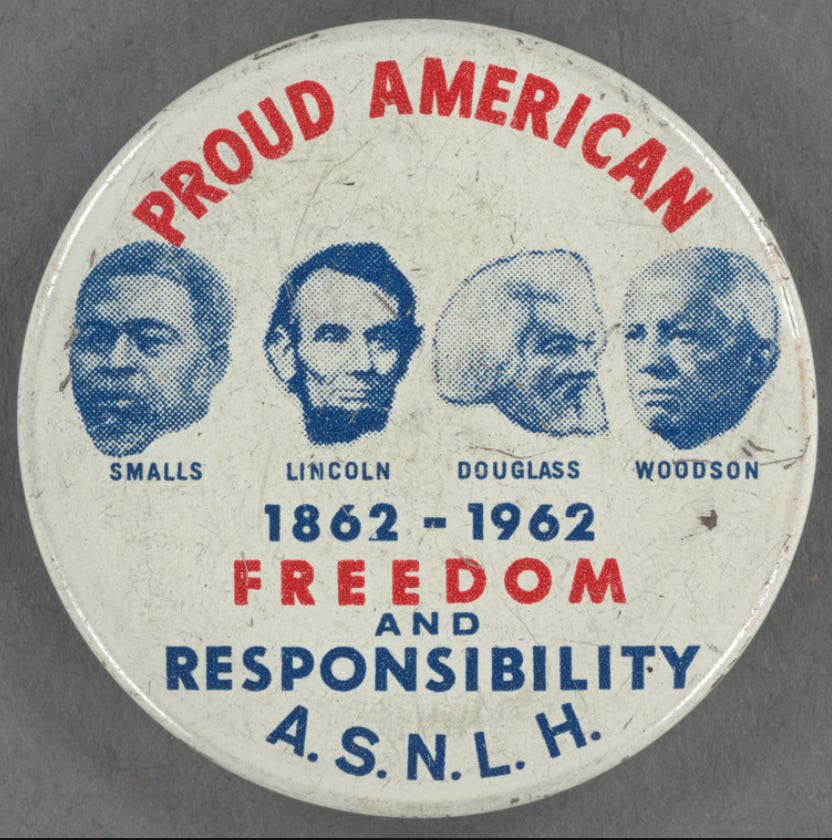

Carter G. Woodson was a smart guy. I mean that both in the “he was a person of letters” way and the “he made some particularly clever moves” sense. A son of Jim Crow Appalachia, Woodson was educated at Berea, University of Chicago and Harvard. He attended the first while serving as principal at a school for the children of Black coal miners. His PhD from the third would be only the second doctorate that institution had ever awarded to a Black person (the first was to W.E.B.Dubois).

It’s impossible to understand what made Woodson’s approach towards academia so sophisticated and subversive without noting the historical context in which he operated. Woodson was among the first generation of Black sons and daughters of newly freed men and women. While the question of Black America’s full humanity is still implicitly on trial today, in Woodson’s day it was a thousand times more explicit and volatile. Having to walk a lonely road in an academy that wasn’t interested in the dignity of his peoples’ history, he saw the need to build institutions that eased that journey for future generations of Black historians. It was one of these institutions, the Association For The Study of Negro Life and History, that would catalyze the movement to establish Black History Week.

It’s worth paying attention to a few decisions Woodson made during this campaign because they’re pretty brilliant. The first was the particular dates he chose for the initial week— in February, inclusive of both Lincoln and Douglass’ birthdays on the 12th and 14th. This was in part to ensure that the new holiday would be rooted in existing Black celebratory traditions (the two men’s birthdays were popular holidays in Black communities at the time). From the beginning, Woodson’s idea was to strengthen, deepen and affirm existing Black thought and action while teaching non-Black people to do the same.

There was a second motive behind choosing those two dates, though. Woodson understood the risk in the “Great men” narratives of history, particularly for Black people. If liberation was allowed to be understood as a gift given TO Black people FROM a white President and a Black activist, it wouldn’t do anything to subvert the narratives of Black inferiority that have always formed the bedrock of white supremacist systems (nor would it teach the world about the power of Black collective action). Woodson’s hope was that mass understanding of the depth and complexity of Black people and history would transform our society’s openness to actual Black liberation.

There was another key way that Woodson was leading with his hopes, however. He started out asking for a mere week (even though this wasn’t his actual goal) because it was an ambitious but pragmatic first step. He consistently made it clear that his true vision was to make symbolic week-long commemorations unnecessary. The initial celebration was to be one more step in institution-building, a good reason to develop a canon of Black history so rich and undeniable that there was no way to ignore Black people the other fifty one weeks of the year.

So, if those were the goals of the initial project, how are we doing? In some ways, there is a story to tell that would make Woodson proud. While navigating academia while Black remains far too difficult, scores upon scores of Black historians and social scientists (as well as compatriots of other races) have continued to build a massive collection of complex, transgressive histories of America through the lens of Blackness. We are fortunate to live in a moment where a wealth of histories that weren’t being written in Woodson’s time are immediately at our fingertips. The question, particularly for white people, is whether we’re looking that gift horse in the mouth.

On that front, there’s at least some evidence that white people could be doing much worse. As easy as it is to poke fun at my own elementary school’s rapid fire quiz bowl approach towards Black History Month, it was one means by which white kids could encounter stories of Black excellence in a variety of fields, a necessary (but insufficient) step towards eventually developing a politics of solidarity rather than charity. If white kids are to grow up to be white adults who truly believe in redistributive justice rather than merely “saving” Black communities, it is important that they encounter as many historical and contemporary examples of Black leadership as possible.

And yet… goodness if we haven’t stalled out in such predictable fashion. Woodson asked for a week… hoping to eventually get a fully integrated year…. and we stopped at a month. Woodson asked us to go beyond celebrating Frederick Douglas and Abraham Lincoln but rather than fully deconstructing the “Great Man” theory of history we just increased the number of Great Men and Women we included in the pile. The way in which Woodson founded the holiday is itself such a beautiful case study of what makes the Black American story uniquely notable— namely, that it is the tale of a people persistently and creatively forging spaces of freedom in the face of a larger society committed to their subjugation. To truly tell that story is to tell of complicated political calculus, of a wide variety of leadership styles and voices. It’s to tell about internal arguments, conflicts and contradictions. It’s to learn from failures and successes alike. And yet, even when we celebrate Black History Month in earnest, we do so in a way that sands down the edges of that more complex story in service of a more muted and one-dimensional After School Special of Black people out here studying peanuts, winning Grammys, giving good speeches and getting tired on buses.

There will be no liberation merely because a few more white people approached Black History Month more thoughtfully. And yet, if Carter Woodson created this tradition as an incremental step forward, it seems fitting for white people to celebrate it in ways that help us tangibly grow our ability to be junior partners in the work of justice. For me, it’s been helpful to hold myself accountable to specific weak spots in my knowledge that I know have limited my organizing and advocacy. As I do so, I’ve tried to be cognizant of the razor’s edge on which I’m balancing— the potential risk that I’m encountering the study of Black history solely through the lens of what it can do for me. Perhaps I’m walking that line well, perhaps I’m doing that poorly, but so far here’s where that’s led me this year:

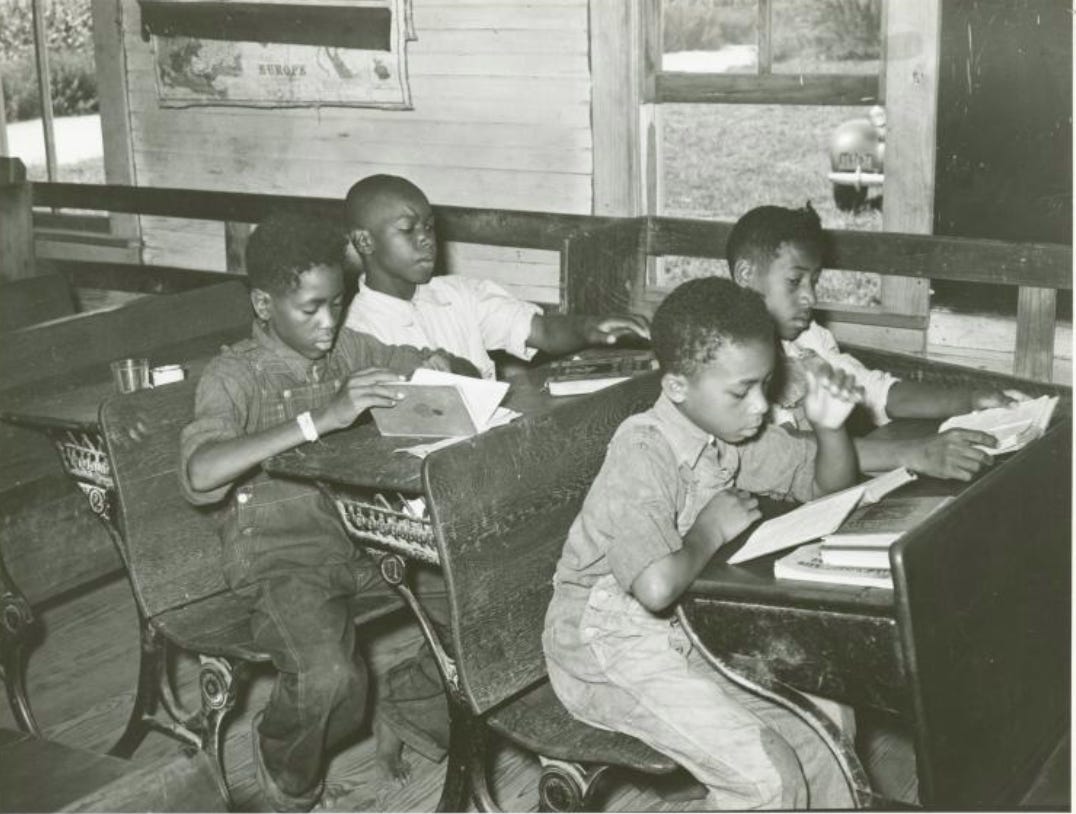

A big part of my professional/personal interests are related to how white parents can be less jerk-ish participants in educational systems that WERE built for their kids. I’ve realized recently, though, that I’ve learned very little from the powerful history of Black parents and educators carving out liberatory spaces in the midst of a system that unequivocally was NOT built for them. My starting point this year is to read this biography of the legendary educator/civil rights pioneer Septima Clark.

As an organizer, I’ve put off researching the more complex, fractious, messy history of the Civil Rights Movement for far too long. I’m starting this year by reading Theoharis’ A More Beautiful and Terrible History, which is one of many attempts to contextualize both the sophisticated and controversial organizing choices deployed in the movement as well as its clear legacy of unfinished business.

Politically, I’m super far to the left. My Black History icons are disproportionally the predictable lefty ones (your Ella Bakers, your Malcolm X’s, your Bayard Rustins, etc.). As a result, I know very little about the history of Black conservatism. However, as I’ve learned just a bit about the path of prominent Black conservatives (like Clarence Thomas), I’ve discovered that many of them emerged from Black Nationalist traditions. Their political evolution stemmed from a sober analysis of what pathways to change are and aren’t available in a white-dominant America. While I’m not necessarily swayed by that analysis, I do believe that it behooves anybody doing anti-racist organizing in white communities to understand the myriad decisions Black people make to triangulate around our collective intransigence. To be honest, I don’t know what answers are to be gained for a white leftist from understanding that calculus better, but I suspect there’s something there. My first step will be Fields’ Black Elephants In The Room.

I’ll make sure I share in a future space if/how these books lead me to reflect/think/listen/act differently. If you are doing and/or plan to do something similar (there’s still over half of the month left!) I’d love to hear about it.

It is true that we have inherited a duct-taped patch work of partial efforts for equity. It isn’t the fault of previous generations of activists and leaders that these past efforts have been insufficient. The story of Carter Woodson’s strategic moves to transform culture and push the zeitgeist has a thousand echoes across both the Black community as well as other communities of color and Indigenous nations. In every case, they did their job by carving out the maximal space for justice allowed by white people of their time. Their hope was that, because of their efforts, future generations of activists of color could lead even more inspiring efforts for change (and future generations of white people would be willing to budge a bit more than our predecessors). If we’re stuck with something partial or insufficient it’s necessary for us contemporary white people to interrogate what’s keeping us stuck here, why we aren’t budging even more, why we’re not offering more oxygen to today’s efforts for justice. Sure, I’ve been reading a few new books this February, but if I’m doing so without asking myself those questions, I’m still not doing the work.

“Black History” by PRhyme (Royce da 5’9” and DJ Premier)

Photo credits here