Little fibs on the prairie

Our stories won't save us, but that doesn't mean we're fully beyond redemption

Top notes: I really do think you’d enjoy joining a Barnraisers Organizing training cohort, or at least I think so if you frequently feel politically hopeless and would like to feel less so. I wrote about them last week. Enrollment link below.

Also, quite sincerely: I remain deeply grateful for everybody who has become a paying subscriber. For those that haven’t but are interested, thanks for considering. Thanks also for all those of you who share this and other pieces far and wide. And finally, a huge thanks to all of you for being here. If you ever need anything or want to say hey, I’m garrett@barnraisersproject.org

This piece is about longing for connection.

There’s this specific genre of viral video. You know this genre. They’re mostly from the Daily Show. Maybe they’re all from the Daily Show, or maybe it just feels that way. Anyways, the whole bit is that an incredulous reporter points a camera and a mic at a bunch of zany conservative true believers, those wacky characters dutifully say wild stuff and everybody clicks the like button and expresses, via emoji, that they are rolling their eyes and laughing until they are crying. A lot of these videos take place at Trump rallies, because of course they do. There was just a new one the other week. It had everything we’ve come to expect from the genre— off-kilter conspiracy theories, ill-advised costumes and the same question I’ve seen smirking liberal reporters ask Trump voters dozens of times: “So, you want to Make America Great Again… when, precisely, was America last great?”

I don’t have to explain the gotcha joke behind the “what year would you magically MAGA-port yourself to?” question. You’re voluntarily reading a newsletter about American Whiteness. You know that the fired-up mark being interviewed will invariably pick a date when life was even worse than it is today for Black, Brown and Indigenous people and the interviewer can pull out their shocked “Really?!? the 1950s?!?” face and you can watch with the reassurance that you are smarter and less racist than they are.

They’re not great videos. They do make you feel good, if you happen to disagree with whomever is sounding wacky or stupid in them. Conservatives have their own version of them. They aren’t good either, but I bet if I were conservative and I watched them, I’d feel pretty good about them too. “Ha!” I’d laugh! “The stupid socialists don’t know that only pure capitalism has ever reduced poverty! “LMAO, the egg-heady gender studies professor gave a long, complicated answer to a question about what makes somebody a woman— they must be either misinformed or disingenuous! I, to the contrary, know what a woman is because they are the people whom I regularly talk over in staff meetings!”

They could be better, these videos. Not more popular, mind you, because to make them better would be to remove all the empty calories that make them so appealing. The questions could be so much more interesting, is the thing. We’re six years into this MAGA phenomena, six years into surface-level Pennsylvania diner interviews and jokey Daily Show clips and I’m still wondering why so many people truly need this, why this particular movement makes them feel less alone, what about this man and the crowds makes them believe that something they feel was lost can be found again, what ghosts they’re chasing.

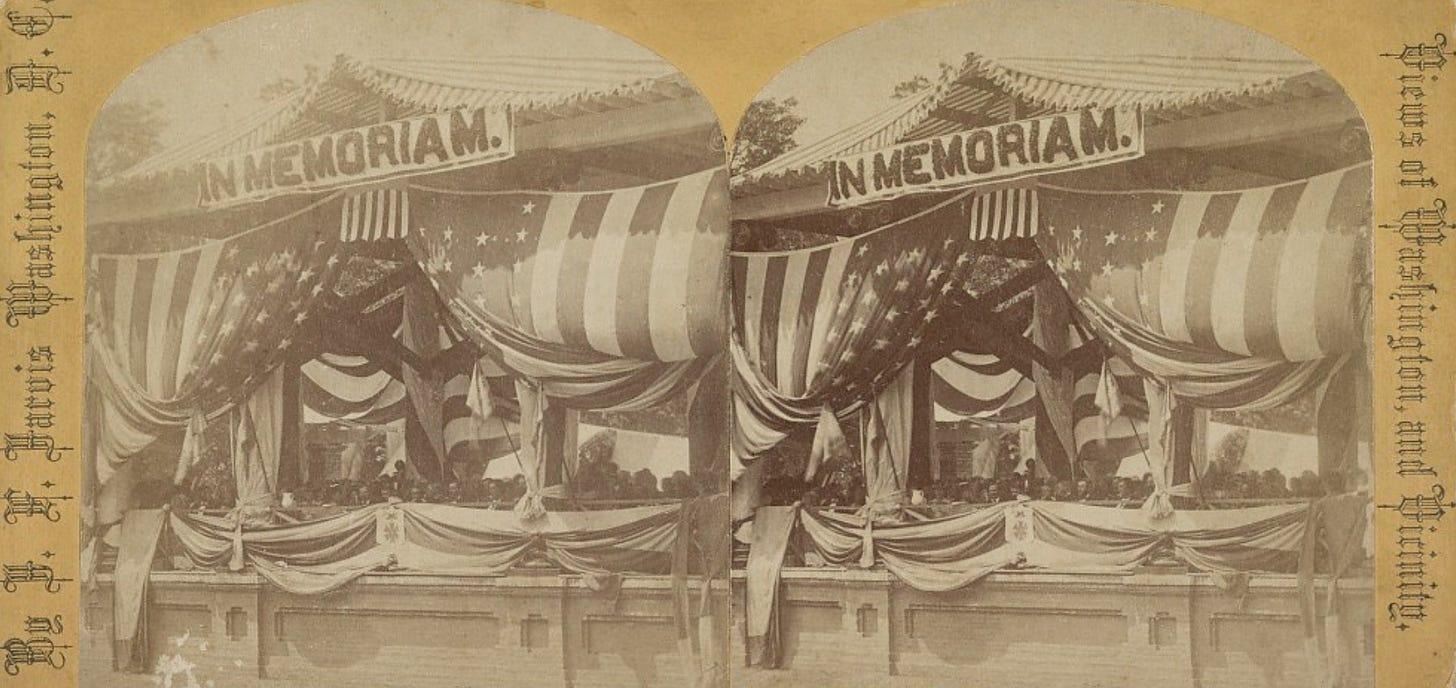

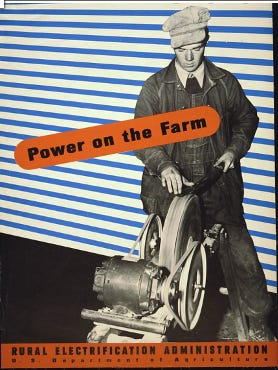

I have the sense that there are more interesting questions to be asked about all of this longing for a Formerly Great America because I’m not above chasing ghosts myself. I have spent too much time with too many Anti-Racist Reading Lists to chase MAGA ghosts, but there’s still plenty of plaintive, searching roads I often find myself wandering down. A few weeks ago, I sent a jumble of images and captions to my book’s editor, who in turn shared them with my publisher’s art department— the first in a series of mysterious steps that will eventually result in my book having a cover. The Word document I tossed their way included a bunch of pictures that inspire me, pictures that I thought captured the vibe of a book that is about White people learning to cast aside individualism and care about community. A few of the pictures were historical- farmer’s union recruitment posters, promotional images for New Deal policies, that sort of stuff. I included a note about how I wanted to spark White people’s imagination for communalism, to say, “we did some of this before, we could do it again.”

A few weeks after sending off the attachment, my Editor, who is Black, passed on a note from the art director, who is South Asian. It was something to the effect of “so… um, this White guy is talking about how he wants folks to remember ‘the good old days’… he does get what’s messed up about that, right?”

Point taken. After the gold rush, after the fire, the descendants of the looters and the killers and the thieves don’t just want all the spoils, we want to look back on our family trees and beam.

There’s not a “but” here. I don’t have a counterpoint. I was appropriately chagrined.

I do have another story though.

A few months ago, I drove to Doland, South Dakota, the tiny speck of East River prairie where my parents grew up and fell in love. I write about Doland quite a bit. There will very likely be a fair amount of Doland in that book whose cover will not nod too romantically towards an imagined Good White Past. A lion’s share of the ghosts I’m chasing are Doland ghosts.

I got into town an hour or so before sunset. It was an absolutely perfect early-summer night, the kind of scene we picture when we pretend that mutant summer bugs and soul-stealing humidity and sneak-attack-thunderstorms don’t exist and all we remember about the summer is that the skies look like they could contain all your hopes and dreams. I spent a few minutes driving up and down Doland’s few remaining streets, face-timing my parents and snapping pictures. Eventually, I got out and traveled the same ground on foot. Mostly, I walked down Humphrey Drive, Doland’s old Main Street, now named for its most famous son, himself one of the ghosts I’ve been chasing.

Doland, South Dakota doesn’t get many visitors these days. It definitely doesn’t get many weirdos in a Prius with America’s Dairyland plates driving up and down its streets and snapping photos of 80% of the town’s remaining free-standing structure. So of course, a couple of old-timers hanging outside the combination Senior’s Center and three-day-a-week barbershop waved me down and asked me what the heck I was doing. Of course those old-timers knew my people, the Gelstons and Buckses. Of course they once took a party-bus down to Branson with my Grandma Vera that I definitely never knew about. Of course they were more than happy to talk.

We packed a lot into that conversation, me and the old-timers, enough that I’m still unpacking it a few months later. I’ll likely write about it from different angles at different points, but for now, here’s something I said that I keep replaying in my mind.

At some point, after we traded memories hazy memories of my Aunts and Uncles, but before we started talking about mechanization and farm consolidation, they asked me what I did for a living and I said that I was an organizer and that I was also writing a book. This of course led to the most cursed but understandable question of all.

“So, what’s the book gonna be about?”

I always answer that question differently. I never quite know what’s gonna come out, because the book’s in progress— it’s a moving target, I don’t want to say something now and have my editor shake his head and tell me “oh that, we’re cutting all that stuff?”

But in that moment, underneath that summer sky that really WAS perfect and not just falsely remembered for being perfect, with these two guys who had kind things to say about my family, I didn’t think. I just blurted out an answer that I hadn’t given before and haven’t given since.

“It’s about how in towns like Doland, people used to take care of each other and bound together, and with the way we’re doing politics these days, I think we’ve lost that.'“

The two old-timers nodded their heads. Of course they agreed with that. It was a real Make America Doland Again answer. I congratulated their good fortune of being products of a virtuous place, a prairie wind break in the midst of a country gone to hell.

And I meant it, too. I had spent the past year unearthing stories of a honeyed Doland-gone-by, a place where the innate rugged individualism of White farmers was consistently tempered by something more radical, something more caring. Doland was once a town of co-ops. It was once a town where the social gospel was preached from the pulpit of the town’s Methodist Church. It’s a place where people took pride in their public institutions, especially their little school with its award-winning debate team. It’s the kind of place that produced one of mid-century America’s most passionate anti-segregationist White Senators, a place where most folks had only ever met the occasional Black person— a road crew member here, a famous baseball player there (Hank Aaron, a passionate pheasant hunter, was known to come around when the season opened).

It isn’t that those stories aren’t true. Every ghost chase begins with something real— a rustling in the leaves, a noise you can’t account for, an object you swear must be out of place. Sometimes, though, we desperately need tiny bits of truth to expand in order to fill a much larger space. Sometimes we need tiny bits of truth to crowd out doubts, to muscle any inconvenient counter-truths to the side.

Sometimes we’re so scared that we’re not going to ever figure this out—both us personally and the other White people who surround us—that we desperately need to imagine that we come from at least partially heroic stock. Or maybe I can’t speak for all of us there. Sometimes, almost always, that’s what scares me to death.

Doland can’t be a town founded on theft and genocide, on Lakota and Dakota warriors dead on the battle field, their families forced onto reservations to make way for White farmers. Doland can’t be one of the hundreds of prairie towns for whose sins Custer literally died. Doland can’t be a place where families only got to go to if they hadn’t taken the Devil’s Bargain of assimilation— if they were no longer Irish refugees or German war resisters or once-starving Norwegians but instead the recipients of all the benefits and curses of American Whiteness. Doland can’t be a community that only truly tut-tutted anti-Black Southern racism because it was a distant concern, something that happened thousands of miles away with no real sacrifice being requested on their part. Doland can’t be a place where farmers didn’t actually band together against big agribusiness. Doland can’t be a place where big money and big individualism would eventually win the day, because for all my romanticism, it was big money and big individualism— railroad trusts and Homestead Acts— that settled the prairie in the first place.

But it is that town. And it’s more than that, but it also is fully that. And it’s ahistorical and immature for me to imagine that it isn’t. It serves nobody for me to tell its story just as a place that was “once a community.” And so, I’m not telling that story, at least not in the simple, aw-shucks, Rockwellian way I said I would when I didn’t want to break the spell with the old-timers.

But what I do understand, at a bone deep level, is what it feels like to wish that story was true, to wish that you come from completely uncomplicated stock, to wish that there is a secret tunnel through which a certain percentage of our White ancestors passed unscathed and that we too can use to crawl our way to freedom.

Michael Chabon wrote an essay about nostalgia a few years ago. It is both immensely lovely and immensely true, the latter in ways that I’m only just discovering.

The nostalgia that arouses such scorn and contempt in American culture—predicated on some imagined greatness of the past or inability to accept the present—is the one that interests me least. The nostalgia that I write about, that I study, that I feel, is the ache that arises from the consciousness of lost connection.

The ache is part of the equation. And goodness I feel that ache. The severed connection. The point in our lineage where every individual virtue in our stories was accompanied by a glaring collective asterisk. That’s the grief of Whiteness— that at some point in history, (perhaps thousands of years ago, perhaps a few decades ago), various sundry groups of Anglo-Saxons and Celts and Slavs and Germans and Iberians and diasporic Ashkenazi Jews grabbed the monkey paw of White Supremacy and chose power over community, disconnection over love, the sword over the plowshares and that once the choice was made, none of us subsequent generations of People Who Are Now Just White could ever look at our past honestly and see a through-line of connection and belonging.

But Chabon goes on. If grief has such a clear source, so too does its opposite.

Nostalgia, most truly and most meaningfully, is the emotional experience—always momentary, always fragile—of having what you lost or never had, of seeing what you missed seeing, of meeting the people you missed knowing

What I’m longing for is connection. And I very well may not find it in the past, not because there is nothing in my family or geographic lineage to be proud of, but because my answers aren’t actually to be found looking backwards. What is meaningful is that I’m longing to be part of something better than what I inherited. What matters is that I’m not the only one doing so.

I know very few other White people who are chasing the specific ghosts of Doland, South Dakota. But we all, us White people, chasing some talismanic, simple story. It is there in the arenas full of fans belting out “Born In The USA!” unironically, pretending that Springsteen isn’t singing about an empire that consigns its own children to poverty and other country’s children to the firing line. It is there in leftist John Brown worship, the belief that somehow we personally must be the heir to the legacy of the One Good White Guy With A Gun. It is there in this week’s liberal paeans not only to Liz Cheney, but to an imagined version of be-knighted Western conservatism that supposedly was once about virtue and small-town neighborliness and not various energy companies’ bottom lines. It is there in every drummed up queer panic and anti-CRT panic currently being initiated by suspiciously well-funded “warrior moms.” It is there, as Tressie McMillan Cottom points out in one of the single best pieces of cultural analysis of the past few years, in the recent cosmopolitan lionization of Dolly Parton, a White Southern working-class-coded vessel for all our dreams of liberation.

We like that story as much as we like Dolly Parton. Rather, we like Dolly Parton because we like that story about who we are. The idea that Dolly is Dolly because of the strength of American diversity is one that pretends to be about how good Dolly is when it is really a story about how good we believe we are. In this story, the soul of America is a progressive teleology that will always, inevitably bend toward justice. America’s soul is immune to everyday evidence of its fallibility, and outright antagonistic to any suggestion that it is more myth than manifest destiny.

We’re all chasing ghosts. We’re all telling stories, if not in order to live, at least in order to bear all the living and dying that has come before us. We’re all mourning the loss of that understandable human desire to look at the place that produced you, the place where you made your life and to be able to say that it is good and therefore you too must be good.

What we don’t have, especially all of us whose ancestors jammed themselves or were jammed into the big tent of Whiteness, is any ability to take uncomplicated reassurance about our goodness from the past. And that would leave us alone, if not for the truth that we’re all sitting with that same longing right next to each other.

I’m stuck with you all. And you’re stuck with me. And there’s nothing in our past that is as good as the future we need to build. And that doesn’t mean that we can’t look at our individual lines and lineages with love and respect and even a very specific, honest pride. But it does mean that there are more lessons to be found in our own, living, breathing longing than in any of the ghosts we’re chasing.

END NOTES:

This week’s song: “After The Gold Rush” by Dolly Parton (sorry Canadians, Dolly and I are claiming Neil’s song as the all-American elegy that it is).

This week’s subscriber’s only discussion: Behavior/mindset changes that might be considered things we ‘should’ do but have also selfishly made our life better! We’re buying analog alarm clarks instead of using our phones! We’re encouraging our teenage sons to find a part-time job in walking distance of our house! We’re playing mah-jong and pickle ball with our rural Southern neighbors! Or, you know, at least one of us is doing each of those things, but we’re all celebrating.

As always, subscriptions are free for Barnraisers alumni, Barnraisers donors and just anybody who would like to be a member and can’t swing it financially right now. Just email me and I’ll add you to the list. Thanks to all paying subscribers for making it possible to welcome other folks in like that.

Whew. Wow. Man. The honesty in this is breathtaking. I love how you ended up here: "There’s nothing in our past that is as good as the future we need to build."

Garrett, this piece resonated with me so much. Thanks for writing this! I think I've mentioned that I've finished a draft of essays on nostalgia, and I also use Chabon's excellent essay in it, and the parts you quoted were also the parts that stood out to me as well. I loved this sentence: "What is meaningful is that I’m longing to be part of something better than what I inherited." That articulated something I've been trying to, so thank you for this.