“Jomeh” by Farhad Mehrad.

There is a giant white arch in Blaine, Washington. It is rectangular and boxy, like an oversized door-frame. It honestly looks more empty-vertical-tomb-like than arch-like, but that’s besides the point. They call it The Peace Arch and it marks the border between Washington State and British Columbia. It congratulates both the U.S. and Canada, I suppose, for putting aside our immense differences and not actively bombing one another. Each side is emblazoned with a load-bearing nicety: “Children of a Common Mother” on one, "Brethren Dwelling Together in Unity” on another.

Oh whatever, let’s take a look at it:

On Saturday night, according to CAIR, 60 Iranian-Americans and Iranians were detained overnight at the Peace Arch Border Crossing. Their crime, of course, was their Persian ancestry, though it’s likely that some among them also committed additional indignities such as “speaking Farsi” and “being Muslim.” They spent the night there while the President of the U.S. blustered on about how much he was looking forward to doing war crimes. As one of the detainees, a twenty-four-year-old medical student, reported, the only reason given for their detention was that “this is just the wrong time for you guys.”

If those detainees had any allusions previous to that evening, it was clear by the end of the night: The arch was referring to somebody else’s “family of a common mother,” one that didn’t include them.

I’m 38. I’ve never known a world in which vainglorious, interchangeable blue-suits haven’t regularly popped up on cable news networks to sell me on the need to shoot some bombs at and run some tanks through one predominately Muslim nation or another.

I was in fourth grade during the first Gulf War. I remember my entire public elementary school being required to write letters of support to President George H.W. Bush, wishing him luck in his war effort. I remember Baltimore Orioles games where the crowd spontaneously burst into chants of “U.S.A! U.S.A!” to celebrate well, I don’t know what exactly… maybe something particularly American that Mike Devereaux or Billy Ripken had just done? Regardless, it was super weird.

I remember Lee Greenwood was everywhere, at all times.

I was in college when we invaded first Afghanistan and then Iraq. I remember pickup trucks emblazoned with the outline of Iraq in target crosshairs. I remember the sitting Senator from my home state publicly referring to Iraqis as “ragheads.” I remember Michael Moore giving a speech opposing the war at the Oscars, an event we are told is a haven for liberal Hollywood virtue-signaling, and getting booed off the stage. I remember an anti-war vigil at my leftist Quaker college getting interrupted by a group of our fellow students waving flags, playing “Bombs Over Baghdad” and laughing down at us. There were a large number of students from the Middle East in attendance at that vigil. The fellas upstairs were just having a laugh, you see. No hard feelings, right?

That time, it was Toby Keith who was everywhere, helpfully reminding us that putting a “boot up your ass” was the American way.

I don’t know what white male country star will be enlisted to soundtrack the upcoming war.

What I do know, though, is that at the time it was easy to dismiss the flag-waving and the chanting and the tough guy anthems as mere jingoism, as a communal “war is a force that gives us meaning” fever-dream. It wasn’t just that though. I wasn’t required to write a letter to my President because my Principal was a warmongering zealot, but because he was legitimately trying to show compassion to the people whom he considered to be siblings from a common mother. His failing wasn’t one of intent, but of an imagination limited by the stories his country had told him. He had a dangerously small definition of who was his community, of who was his family.

It’s easy for me to offer that grace, though. I’m not the one stuck on the outside of a racist boundary line. I’m not holed up in Blaine, Washington, staring at a giant white arch while it actively lies to my face.

We still don’t know what will become of our current rear-end-first stumble into armed conflict in Iran. There is something telling, however, about the way in which we Americans have discussed the conflict thus far. From Presidential candidates to media pundits, the overwhelming chorus of opposition to the Soleimani assassination has been some version of Joe Biden’s “we tossed a stick of dynamite in a tinderbox” statement.

To put a finer point on it, we’re being told even by those who oppose this war that the reason we shouldn’t be attacking other country’s leaders with drones isn’t because doing so might cause pain and suffering to that country’s populace. It’s because citizens of that country are a “tinderbox,” reactionaries whom we must fear because of their irrationality. Iranians are not to be treated with dignity for their own sake, but because of what we believe they’re capable of doing if pushed to the edge. Ironically, the only public figure in America who is (accidentally) making note of Iran’s vibrance and depth is Trump himself, through his threat to attack fifty-two prominent cultural sites. (An aside: The unintentional impact of these particular bloviations is to remind us Americans, that, we, um, don’t really have fifty two prominent world cultural sites of our own— after forty or so we’d have to start rolling out particularly notable Bass Pro Shops).

Iranian culture exists only when there are threats to be made.

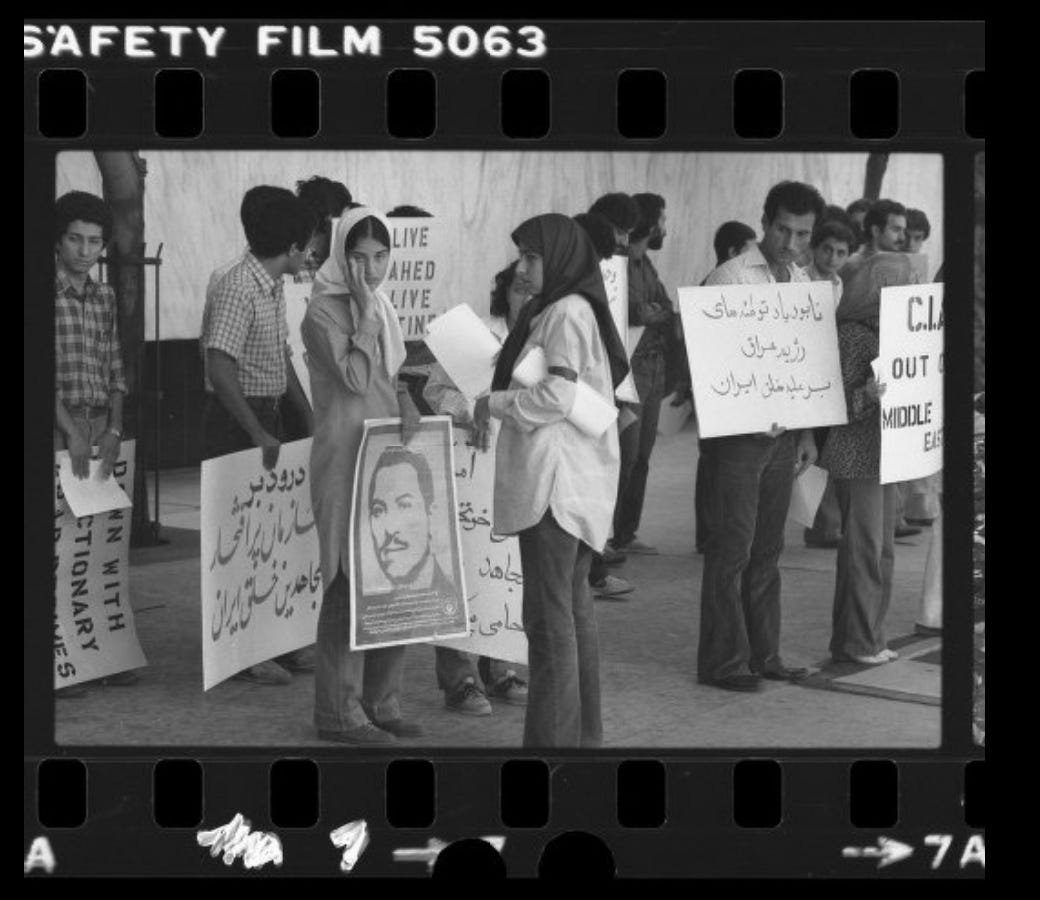

This is not a new belief-system, of course. The idea of the Orientalist other, which must be either defeated, appeased or avoided, is what precipitated the Crusades. It’s what has enabled a constant belief that any resource under their sand is ours. It’s what has justified coups and proxy-wars and over-a-half-century of constant destabilization that we’ve been told for years is what got us to this place. Turns out, the border guard who told the detained med student that “this isn’t a good time for you guys [to be around Westerners]” could have meant this weekend, the past sixty years or the past thousand years.

You know all this, but we take for granted how foreign it is for Americans to truly consider Iranians or Iraqis or Palestinians or Syrians or Afghanis to be human beings, let alone ones with whom we might share any degree of interconnectedness.

This past week, an inspiring friend of mine, an Iranian-Korean City-Councilmember in St. Paul, MN, wrote a beautiful piece about her family, about the humanity of Iranian-Americans, about the fear that the Iranian diaspora feels right now. It is getting a good deal of attention, all of it deserved. But the fact remains that, in this country, in 2020, an Iranian-American elected official has to publish a piece in a major paper to remind her fellow Americans that people who have last names like hers are in fact worthy of love and compassion.

“If I sit silently, I have sinned”

-Dr. Mohammad Mossadegh, Prime Minister of Iran (1951-1953), champion of popular democracy and economic justice. Deposed in a CIA coup.

There was a time when millions could participate in an anti-war movement at least partially out of their own self-interest. Mandatory conscription is good for that. For my entire lifetime as an American, though, that hasn’t been our reality. And while there are thousands upon thousands of poor folks, disproportionally Black and Brown and Indigenous, for whom conscription is technically voluntary but economically necessary, many Americans today are able to choose to not be sent to war.

This means, for those of us with that choice, that to be fully and passionately anti-war requires a radical and active daily redefinition of your community. From the moment that war drums start beating, every message you receive will define that community solely as other Americans, especially as white Americans. Those will be the casualties that are mourned, those will be the profiles in courage that are celebrated. Again, it’s already happening: We are the potential victims, Iranians are merely the tinderbox set to blow. With the force of this discourse coming your way, it will be impossible to imagine differently, to believe yourself to be siblings with Iranians (and the Iranian Diaspora), without making an active effort to do so.

This is one reason why I believe so deeply in the power and necessity of daily anti-racist action close to home, especially if you’re white. Because it isn’t just Iranians who you’re taught aren’t your siblings. It’s the Black kids whose schools you moved to the suburbs to avoid. It’s the undocumented Guatemalans whose deportations your church tacitly if not actively supports. It’s the missing and murdered Indigenous women whom none of us notice. It’s the Hmong families who’ve been living in your towns for multiple generations but who are still viewed as foreign invaders. It’s the kids playing on a busted-up playground on the wrong side of the tracks because the cool tech company you work for is avoiding its property taxes. It is all the people you are taught to either ignore, fear or pity, but never to stand alongside.

The better we are at working alongside our physical neighbors, the better we’ll be at working alongside our global neighbors. Right now, we need to do both at the same time.

There’s a popular saying in activist circles: “Your heart is a muscle the size of your fist.” It’s a necessary sentiment for our current moment. We are on the precipice of war. If ever there was a time for fists in the air, it’s now. Protests and civil disobedience and refusals of service and urgent calls to Congress are all urgent and necessary.

But if that aphorism is, in fact, anatomically true, it means that your heart is also roughly the size of your hand doing other fist-like things: clenching a pen, wrapping itself around a shovel or holding the hand of a neighbor.

To be honest, many of our hearts are pretty damn weak right now, because we’re asked to only truly exercise that muscle for folks who look like us. But we’ve got a war to oppose. And sadly, after it passes, another will come our way before too long. It’s well past time to build those muscles stronger, in as many ways as possible.

“I ain’t Marching Anymore” by Phil Ochs

All photo attributions can be found here.