Out of the Corner

"10 Movies, 10 Stories of Whiteness" Issue Seven: Dirty Dancing, Jewishness and Who Gets To Be White

Top notes (from Garrett)

Full disclosure: Was this whole movie series just an excuse to get the incomparable Sarah Wheeler to write about Dirty Dancing? I mean, probably. You can read all about Sarah at the end of this piece, but suffice to say that if you’re not already familiar with her writing, you’re in for an absolute treat.

This is the second week in a row that I’ve welcomed in a guest writer, so in honor of this continuing to be the kind of establishment that (thanks to your support) can pay contributors for their wisdom, I’ve extended the subscription sale through the end of the week (Saturday the 5th). 20% off for a year. What a deal. The link below should do the trick.

Oh, and if you’re new here and you’re not sure what this whole “movie series” is about, you can find an explainer here and all of the previous entries here. I highly recommend the two other guest essays in particular—

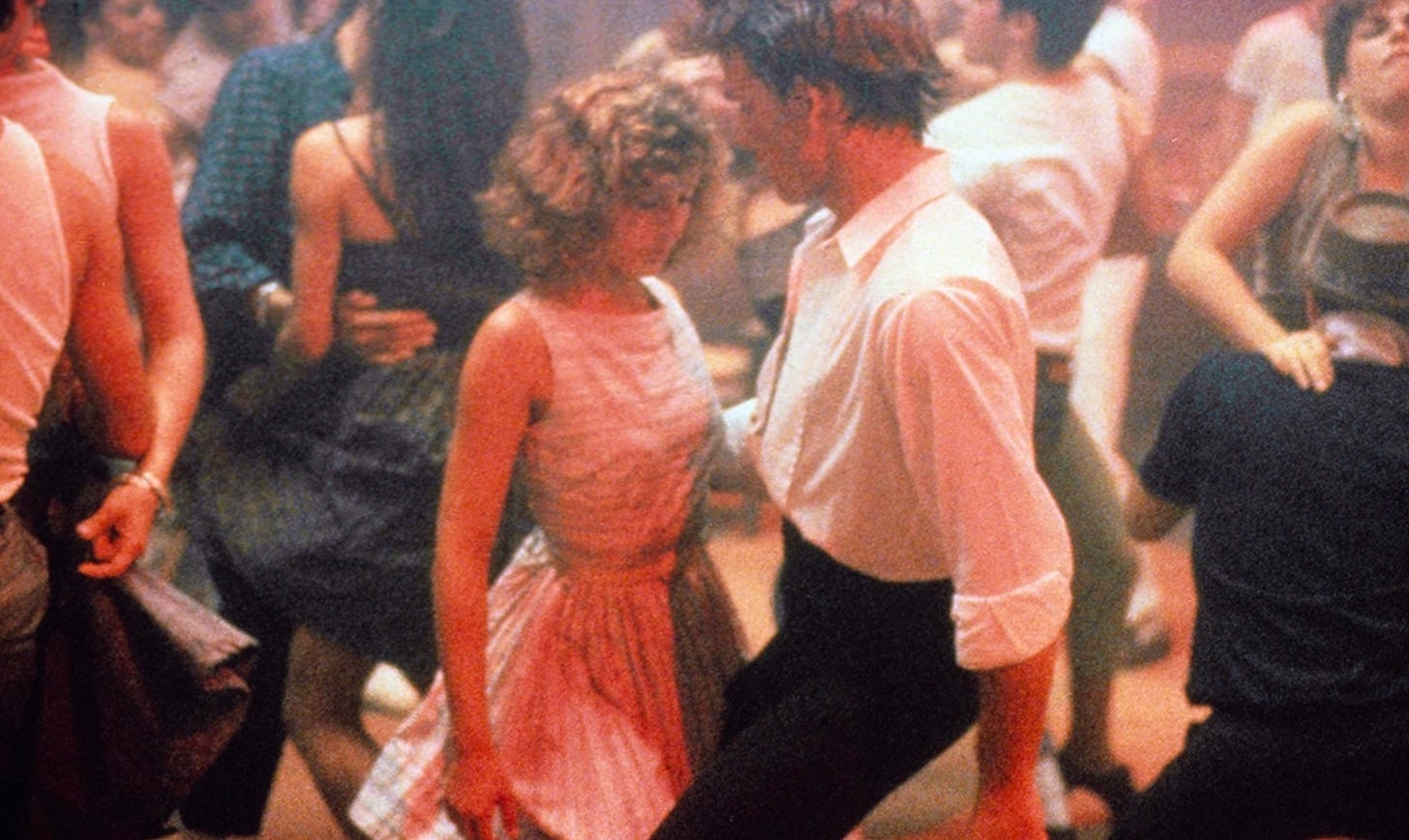

on Pretty In Pink and on Gone With The Wind.I didn’t want to rewatch Dirty Dancing, the iconic 1987 film that shaped the cultural ether of my youth. It wasn’t because I thought I wouldn’t enjoy it. I knew I would, and I did. But I didn’t want to burst the tender bubble of my patchy childhood memory of it. I was interested in the film, sure, but also the snippets that had remained salient for me all of these years, and why. Was there something about carrying a watermelon? Did Baby’s dad really give the villain a check for medical school, only to rip it up? Did Jennifer Grey and Patrick Swayze fully bone at some point? Or was the boning only implied?

It’s amazing how a film, which I watched many, many times between my childhood and my twenties, can teach you important lessons about family dynamics, class, morality, the threats to women’s bodies, and of course, desire, and still leave you with very few sharp details. That’s how memory works. And childhood. And culture really — it’s just a jumble of impressions we can rarely trace to one specific instance, but which we still believe in, wholly.

Dirty Dancing was released in the eighties, but it is set in August, 1963, the same month as the March on Washington and Martin Luther King’s famous I Have A Dream speech, and two years before the first U.S. ground troops were deployed to Vietnam. It tells the tale of a formative summer vacation for the teenaged Baby Houseman (Jennifer Grey) and her family at Kellerman’s, one of the many country-ish, upper-middle class resorts that proliferated in places like the Catskills in the ‘60s.

While Baby’s older, boy-crazed sister falls for a college-educated waiter, Robbie, Baby makes friends with the staff, kids of color and “ethnic Whites” (Italian and German-Americans), eventually falling for Johnny Castle (Patrick Swayze), the dance instructor-by-day, gigolo-by-night, who teaches her how to dance, unleashes her sexuality, and helps her settle into a more sophisticated brand of ethics than the Peace-Corps style self-righteousness she brought with her. On the way, there’s a botched abortion, an elderly serial thief whose crimes are blamed on Johnny, a whole lot of lessons about class, integrity, and generational misunderstandings and, of course, some very dirty dancing. The film uses music as a metaphor for how much is changing with the youth of the 60s. Like the conservative social norms of the 1950s, the Catskills resorts are dying out. Kids these days want to go to Europe in the summer, and they also want to flaunt their sexuality, break down racial and class barriers and buck against the expectations of their parents. Well, some of them do, at least.

In my favorite scene from the film, one which displays just how well cast these two leads were, how deftly they shied away from an almost inevitable corniness, Johnny breaks into his own car and drives Baby off the resort grounds, in the rain no less! Baby tells him, “You’re wild, you’re really wild, you’re really really…you’re so wild you’re crazy and….you’re making me laugh!”

One of the things I couldn’t quite recall about the film was when, and how, the main characters were identified as Jewish. As it turns out, they never are. Though every Jew I know considers Dirty Dancing to be a Jewish movie, the vast majority of viewers, I learned, do not. Perhaps you don’t. A screenwriter friend who has closely studied the film first brought this to my attention, and so when I did rewatch the movie, I kept looking for the moment when I could say “There, that’s when we know they’re Jews!” But that moment never comes.

While the original script is full of Yiddish, and lines like “I forgot, you read from a different bible” and “Jews hate Catholics” (both spoken by Johnny), the final version in the film has none of that. The writer, Eleanor Bergstein (def a Jew), supposedly based the movie on her own childhood experiences visiting the Catskills, and the dog whistles to other Jews can be found in the final cut. Jews know the movie is about Jews. We recognize the Catskills resort culture, the themes of over-valuing education, the focus on civil rights. We recognized Jerry Orbach, the actor who played Baby’s father, as having Jewish blood. Also, there’s the thing with the nose. Baby has the kind of nose that many Jewish girls of her generation got surgically corrected (my step-father told me that he had girlfriends whose fathers forced nose jobs upon them). I remember as a child being aware that Jennifer Grey had gotten a nose job post-Dirty Dancing, and understanding that this was somehow both wise and shameful. I could write another 2000 words about the fraught relationship between Jews and nose jobs, but all I’ll say about it here is that it serves as another example of how some Jews clamored for classification as White, while others lived, and continue to live, in ambivalence about it.

Without this subtle understanding of the overt Judaism that never made it into the film, Dirty Dancing is a movie about White people and racism and class. It’s about ethnic Whites and the scrambling for status in a racialized society. But for a Jew, or someone who sees this movie as not just a race and class and culture movie, but one that deals with race and class and culture as it relates to being Jewish in America, it’s a little more complicated than that.

In her 1998 book, “How Jews Became White Folks and What The Says About Race in America,” Karen Brodkin writes: “The American ethnoracial map–who is assigned to each of these poles–is continually changing, although the binary of black and white is not.” The question of whether Jews are White, and if so, how and why they became White, belies the artificial, often arbitrary construction of race in America, the centerpiece of which are the classifications of White and Black. When I was in graduate school, I remember reading a sociological study of high school students who immigrated from the Dominican Republic to Rhode Island. They were shocked to find themselves, upon arrival, being told they were “Black.” To me, Dirty Dancing isn’t just about having “the time of our lives,” it’s about the absurdity of racial politics and the shifting sands of who belongs to what race.

My mother’s family grew up going from their home in New Jersey to Kutcher’s, a more middle-class version of Kellerman’s, in the summer. I visited Kutcher’s in the 1990s to celebrate my grandparents 50th anniversary. By then it was a relic of the past, with a depressing vibe and a senior home smell. We played shuffleboard and visited the arcade, where my older cousin won a stuffy from the claw machine and took on a god-like status amongst the younger set. We took in a performance by Chubby Checker, who I conflated with Chuck Berry, a source of great confusion for everyone I spoke to about it.

These places represented a Jewish-American history that I had little understanding of, a world where Jews–excluded from the leisure spaces of non-Jewish Whites– built their own. My mother’s father had escaped the pogroms in Eastern Europe at the beginning of the 20th century, and immigrated to New Jersey where he lived, two families to an apartment with a sheet hanging down the middle. He turned his father’s glass cart into an auto-glass shop, married and had kids, and moved to Patterson, a working-class town laden with Jews. My mother was born in 1945, just after the last concentration camps were liberated, and, like many Jewish Boomers, her infancy was shadowed by the aftermath of the war – the rising understanding of what had actually been done to the Jews, the weight of U.S. complacency, which didn’t end when the war did (the U.S. did not accept large groups of Jewish war refugees until 1948, but rather, let them languish in horrific “displacement camps.”) But growing up in Patterson, my mother never thought much about race and class. They were who they were, and though there were parts of American society that were clearly off-limits to them, they seemed to have what they needed.

When she was ten, for reasons she never quite understood (her father often insisted it was because her mother needed air conditioning), her father moved the family to Glen Rock, a more affluent town where there were no Jews to speak of. When someone painted a swastika (twice), on the family’s house, neighbors helped wash it off, and my grandfather sobbed and sobbed because– my mother believed– he was shocked that it could happen here. Crank callers harassed them, telling them to go back where they came from. But it mostly passed. My mother was her high-school valedictorian. At her graduation, her best friend’s mom told her she loved her so much she almost forgot she was Jewish. My mother got a scholarship to college, where her roommate slept with the light on and peered down at her sleeping head in the night to see if she had horns. She joined a Jewish sorority, because her friends in the “normal” one had been told if they invited her, it would incite chaos. But in general, she thrived. She did what many Jews of her generation did and joined the civil rights movement. She wrote in her college newspaper about the ills of apartheid. Her parents didn’t discourage her from fraternizing with anyone, though they made it clear she should marry a Jew (she did not). She dated Jews, White “goys” (what we call non-Jews), Black men. She moved up in the world.

During college, my mother actually worked summers at Grossinger’s, the Jewish Catskills resort that Dirty Dancing’s Kellerman’s is modeled after. According to her, as in the film, the class wars there were alive and well. The salaried staff— local working-class Whites— despised the White college kids, Jewish and non, who made up the summer staff and whom they considered to be elitist softies infringing on their turf. Of course, this crew had a lot to lose, financially and status-wise, and their frustration about their position as victims of a class system was both understandable and relevant to today’s climate. When my mom showed up early to snag a coveted bread basket for each of her dinner tables, the regular staff would swoop in late and move the baskets from her tables to theirs. When she passed by with her arms balancing an overhead tray, they would snatch the tips from her pockets and smile. My mother identified with some of the Jewish clientele – they were interested in her studies, happy to tip her generously since she was making a name for herself as a representative of her people, wanted to talk about Israel and their dismay at racial violence there. They were what us liberal Jews think all Jews are like; curious, intellectual, and deeply compassionate and egalitarian. But then there were the Jewish patrons who let their wealth carry them away. At an all-inclusive resort, they ordered three different breakfasts for their children, leaving heaps of food on the plate, something my mother, whose parents had grown up in abject poverty, found morally reprehensible.

My mother’s family could not afford to summer at a place like Grossinger’s or Fetterman’s. These were places for wealthy Jews. But she is quick to point out that this was a community that was prideful about their Judaism, that despite their social striving, did not want to wash it out. It was a different time. Echoing a scene from the beginning of Dirty Dancing, the kitchen manager gave a detailed training–much like one would get these days about HIPAA compliance–, about what kinds of sexual harassment they should allow and what they shouldn’t. An ass pat was to be permitted,a grab not. She thought their biggest motivation for dissuading the staff from being pressured into sex by the clientele was mostly about the resort’s reputation – they didn’t want to be seen as that kind of place.

I was raised reform, a sect of liberal Judaism that talks about God but mostly concerns itself with being a good person who moves through the world with kindness, and a sense of just purpose. In an oft-quoted tale in my kind of synagogues, a young Isador Rabi, the Nobel-winning scientist, claimed that his mother asked him every day after school not what he’d learned that day, but whether he’d asked any good questions. This was what Judaism meant to us, at its core. There were plenty of Jews around growing up. To me and my siblings, anti-semitism was over, and we found our elders’ obsession with it tiring.

Without a name or face that implied Judaism, I have always been able to choose when to reveal that aspect of my identity — such as when I needed to relate something using a Yiddish word, to ask about plans for the new year, to justify the telling of an off-collar joke. I had sympathy for the trauma of older generations, but I couldn’t access their anxiety anywhere in my own body. The good reason for that, of course, was that I’d never experienced discrimination for being Jewish, not once. Though the American Jews who witnessed the Holocaust from afar would never quite let down their guard, they were allowed in on the American dream. And Jews like me were the product of such a dream coming true, which, of course, was deeply tied up in race, and the slow movement of Jews from a racialized group to a religion practiced by people who were mostly (I have to acknowledge the Jews in this country, though they are in the minority, who are not light-skinned) seen as White.

Just after Donald Trump was elected and anti-semitism started popping up again in American culture, the journalist Emma Green wrote an article in the Atlantic titled “Are Jews White.” She writes:

“Jewish identity in America is inherently paradoxical and contradictory,” says Eric Goldstein, an associate professor of history at Emory University. “What you have is a group that was historically considered, and considered itself, an outsider group, a persecuted minority. In the space of two generations, they’ve become one of the most successful, integrated groups in American society—by many accounts, part of the establishment. And there’s a lot of dissonance between those two positions.”

Jonathan Greenblatt, the CEO of the Anti-Defamation League, argued that Jews do grapple with race—and in fact, they have been at the forefront of struggles for racial equality like the civil-rights movement. “There’s no doubt that the vast majority of American Jews live with what we would call white privilege,” he says. “They aren’t looked at twice when they walk into a store. They aren’t looked at twice by someone in uniform … That obviously isn’t a privilege that people of color have the luxury of enjoying.” And yet, even though light-skinned Jews may benefit from being perceived as white, “[Jewish] identity is shaped by these exogenous forces—ostracism, and exile, and other forms of persecution [like] extermination. I think there is this sense of shared struggle … programmed into the DNA of the Jewish people.”

In Dirty Dancing, Baby, and even her father, exemplify the sharing of the racialized struggle that so many Jews find key to their American identities. She is going into the Peace Corps, and even the rich and dorky grandson of Kellerman’s owner, who is supposed to be a total d-bag, is planning on journeying down South with the bus boys to join the Freedom Riders. In the script, the Jewish preoccupation with standing by Black Americans is even more pronounced. Baby’s dad makes an offhand comment and the tragedy of police setting dogs on protestors in Birmingham. In a very odd scene that was entirely cut from the movie, the Latinx bandleader is trying to coax the young Black trumpet player into the hotel pool by saying “it’s not like that here!” When the trumpet player hesitates, Baby pretends to accidentally bump him in, and her dad watches on with pride. Though the movie clearly positions Baby as fumbling and a little thirsty in her attempts to be a do-gooder, it’s not clear whether it empathizes with the trumpet player as merely being a vehicle for the Houseman’s public morality, or with them for moving the arc of justice along.

Either way, the movie makes clear that these people are allies to Blacks. And yet, the Jewish characters constantly mistrust and mistreat the other “ethnic Whites,” who the douchy Jewish grandson refers to as a “necessary evil” of running a resort. Those folks work the background jobs at Kellerman’s, whereas the Jewish college students, like Robbie the dickhead (he goes to Cornell, natch), are waiters. Of course, as the Black/White discourse of US racial politics allows, Black people are not a threat to Jews. But other White people are. As Ivy-League Robbie says, before handing Baby a copy of The Fountainhead (script, not film) “Some people count, and some people don’t.” Of course, we see that ethos firsthand when Robbie leaves Penny, the lower-class White dance teacher, to fend herself with the pregnancy they both created. In a series of events I only partially understood as a child, Penny frets about not having the money for an illegal abortion, Baby borrows it from her dad under false pretenses, the abortion is gnarly and Dr. Houseman is roused to pick up the pieces, he thinks Johnny is to blame for the pregnancy, and that Robbie is a golden boy. He is blinded by his own class, and race allegiances.

Jewish folks often seem to want to be exonerated from racial politics in America, citing their support of Black Americans as evidence of their disinterest in joining in the American tradition of racism. But if you take these deleted scenes along with the film, the writer seems to be reminding us that Jews like the Housemans and the Kellerman family are still racist, but towards the ethnic Whites with whom they are in closer proximity and competition.

In the script, Dr. Houseman gives a speech about his own prejudice towards the Johnny Castles of the world. Though he stands up for Black folks, he has nothing but vitriol for the lower-class Whites. He tells Baby about how Johnny’s “kind” used to beat him and his sister up every day on the way to school. The message is; Jews like Dr. Houseman pulled themselves up by their bootstraps. They studied hard. They didn’t resort to violence. They are better than, more worthy of the gifts of Whiteness in America than the kind who appear to be wasting them.

It’s important to remember that Dirty Dancing was an indie movie. Though it was nominated for Golden Globes for Best Picture and Best Actor and Actress, its only Oscar consideration was for Best Song (it won). It won an Independent Spirit Award for Best First Feature, which had gone to She’s Gotta Have It the year prior. Nobody involved in the movie’s production expected it to become a classic. It was weird and edgy, kind of a unicorn. It was the first narrative film directed by Emile Ardolino, an openly gay, Italian-American who died of AIDS six years after its release. Eleanor Bergstein never wrote another hit. And yes, Swayze really was just oozing with sexuality and they boned like crazy and it was all kind of exciting for the times.

And yet, the movie wasn’t made in 1963, it was made in 1987, when we had 25 more years of the American racial experiment under our belts. In the sixties, this movie would be explicitly about Jews, it would have been too confusing otherwise. But in the eighties, Jews were so integrated and absorbed by the American racial system that it just seemed to be another movie about White people. And while in the time between the movie’s setting and its writing, some racialized groups, like Jews, had been largely granted status as Whites, others were allowed provisional freedoms, and still others continued to be largely oppressed. Is this a movie about nostalgia not just for the doo wop era, but for a pre-civil rights alternate universe that somehow resulted in a different future?

In the end, if you take the era at face value, the message is hopeful. The next generation is not as hung up on racial classification and stratification as the old guard. Yes, Baby is naive, but she maintains the moral high ground. “I’m sorry I let you down, daddy” she tells Dr. Houseman. “But you let me down too.” Her father, though he understands more about the complexities of the real world than her, is cowed. His tribalism, which led him to be suspicious of a man with a wild haircut but a heart (and voice! and ass!) of gold, and trusting of a baddie who looked like him, led him astray. He rips up Robbie’s med school recommendation letter (not a check after all), apologizes, and returns home, we can imagine, with a little more understanding of where the world is headed.

As a child, I was never made to feel ashamed of my Judaism, as my mother had. But, even coming from the “colorblind” liberal ideology of the 1990s, I was aware that Whiteness was, in some ways, shameful. I was in lots of spaces, in a diverse city, where I was one of only a handful of White people. And though I knew that this fact granted me freedoms my friends of color did not have, I also knew that it was, at the very least, not cool, and at worse, quite bad to be White. As a middle-schooler, when I discovered, and soon became obsessed with, the history of the Jewish Holocaust, I was disturbed, but ultimately more relieved than grieved. Ah hah! I thought. That’s proof. My history was not entirely the same as other “White” Americans, like my father’s family, Mayflower descendants and enslavers. I was not on the side of the oppressors, but the oppressed. Then I learned about Israel’s systematic violence towards and oppression of Palestinians, and the grief came. In the game of racism, everyone gets to play.

At the 50th birthday party of a friend this past weekend, the hosts started the night off with a rousing and well-rehearsed rendition of the theme song from Dirty Dancing, “(I’ve Had) The Time of My Life,” by Bill Medley and Jennifer Warnes. Everyone knew the words. Like in the closing scene of the film, where Swayze delivers the famous “Nobody puts Baby in the corner,” line, Baby finally gets to integrate the two versions of herself (clear-headed 1950s Jewish teen and sensual 1960s adult) she’s been grappling with all summer, and Mrs. Houseman whispers “I think she gets it from me,” everyone danced. The crowd, young and old, were energized. It’s been another twenty-five years since the movie came out, and it is still relevant.

So, then, are the questions of whether Jews are White, and what being White even means. Some American Jews are a bit afraid at the moment, and I would hope that somewhere in that anxiety is an acknowledgement of the complex security we’ve seemingly won here. I ask myself often, what can I learn from my family history? Can I both be proud of my people’s commitment to fighting for the freedoms of others and suspicious of our complacency with the process by which we achieved our own freedoms? What is reprehensible in how Jews have distanced ourselves from other Americans, and what is an attempt to hold onto some kind of identity other than the all-consuming one of Whiteness?

As one of the few American ethnic groups who have been repositioned in just a generation or two, and as one that values intellectual and moral relentlessness above all else, I hope Jews keep asking themselves these questions with me. Because like Swayze in the rain, race in America is wild. And like in the film, it isn’t always clear who are the good guys and who are the bad guys. Sometimes, you’re a little bit of both. Maybe that’s what Baby understood the summer she grew up. Maybe, as a second generation Jew who has the luxury of stopping to look around me, I am starting to understand that as well.

Sarah Wheeler is so many things: A teacher, an educational psychologist, a mom, and a crafter of very good emails about the NBA and texts about “Pony” by Ginuine. She is also a hell of a writer (Garrett wrote this bio, this is not Sarah bragging about herself) whose work has appeared in The Cut, The New York Times, The San Francisco Chronicle, HuffPost, McSweeney’s, Romper (where she writes a regular parenting column) and her own newsletter, Mompsreading. She lives in Oakland, the Catskills of the Bay Area.

End notes (from Garrett):

Yesterday, I got a text from Sarah with a link to “(I’ve Had) The Time of My Life,” the Dirty Dancing soundtrack cornerstone performed by Medley and Warnes with the message “still a banger imho.” I agree! It is still a banger. Just listen to that synth bass. And all those tempo changes. But a great song! And one of the 1980’s best parenthetical song titles! Did Sarah and I consider calling this essay “(I’ve Had) the L’Chaim Of My Life?” Not really, but we texted about it. Cooler heads prevailed. Also, Sarah recommended that I share the version that plays at the end of the movie rather than a lesser Youtube clip. Another good call on her part! Just feast your eyes on all that dancing! It’s so dirty!

As always, the entire Song of the Week playlist is available on Apple Music or Spotify

This was FASCINATING and I'm sending to all my (Jewish) family :) I was today years old when I realized that of course it was a Jewish family. But my family are Jews from Syria (originally referred to ourselves as Sephardic but now use the Mizrahi term) so I have never related to the Catskills and Ashkenazi of it all, but now I need to watch it immediately again with this lens. Thank you so much for this wonderful piece.

I love this essay! My only quibble is that the Fountainhead line is 100% in the movie. The movie's confident association of an Ayn Rand worldview with extreme douchebaggery is one of my favorite things in the world!