Partying for your right to fight

"10 Movies, 10 Stories of Whiteness" Issue Five: Top Gun: Maverick and America's least sympathetic rebels

Welcome to the sixth edition of The White Pages Summer Movie Series. It’s been a blast. If you’re not sure what this is all about, here’s an explainer, and here’s all the back issues. We have a guest essay lined up for next week— on Gone With The Wind, no less— so get excited.

I don’t have any particular beef with the wildly popular country music star Kenny Chesney. As a fellow hat enthusiast, I admire his commitment to signature headgear. “Get Along” is a pretty fun song, though I think it’s funny that one of Chesney’s solutions for our nation’s many divides is that we should all “buy a boat.” He seems amiable and fun and was once married to Renée Zellweger. He made a goofy video for his “Chillaxification” tour, which was sadly canceled because of Covid. Points for the name “Kenny Chesney’s Chillaxification Tour” though. What a goofy, unironic guy. I don’t mind that he seems to love beaches, which are decidedly not my thing; nor do I mind that his fans call themselves “No Shoes Nation” even though I have sensitive feet and enjoy wearing shoes.

It is with no enmity nor disrespect towards Mr. Chesney that I note that his particular brand of contemporary country music is thoroughly milquetoast– both sonically and lyrically. He makes mid-tempo, beachy jams about his favorite season (summer!), the gender to which he finds himself attracted (women!), and his preferred alcoholic drink (beer! or maybe tequila!). He’s not trying to rattle any cages or speak any profound truths about the human condition.

Chesney’s intentional blandness matters because it is at the core of one of the great recent mysteries of the American concert tour industry. You see, for a good stretch of the 2010s, it was not uncommon for Kenny Chesney concerts to devolve into chaos. We’re talking assaults, looting, monumental piles of garbage— that kind of chaos. Chesney’s Pittsburgh tour stop was particularly infamous, but No Shoes Nation’s Western Pennsylvania members weren’t the sole culprits. Enjoy, if you will, a selection of headlines about the Kenny Chesney Concert Experience and ask yourself… Does this sound like chillaxification to you?

Kenny Chesney concert ends with fights, arrests, huge mess.

Kenny Chesney fans trash Pittsburgh again

Extra patrols added after brawl at Kenny Chesney Concert

Kenny Chesney concert in photos: 37 hospitalized and 48 tons of garbage

And, of course…

Kenny Chesney Sparks White Riot at Lambeau

OK, “mystery” might be overstating it. Chesney’s crowds (particularly the rowdier subsets of his crowds) are overwhelmingly White, young and male. While there is surely a diversity of class backgrounds represented in No Shoes Nation, it’s safe to assume that the median concert attendee is financially comfortable enough to afford hefty ticket fees. You can already connect the dots to the various root causes at play. Toxic masculinity plus alcohol plus enough racial (and likely financial) privilege to not have to worry about the implications of your actions is as good an equation as any for poor public behavior. Listen, I’m not naive. I once lived a block away from frat row in a Big Ten college town. I know for whom the couch burns and the beer bong guzzles.

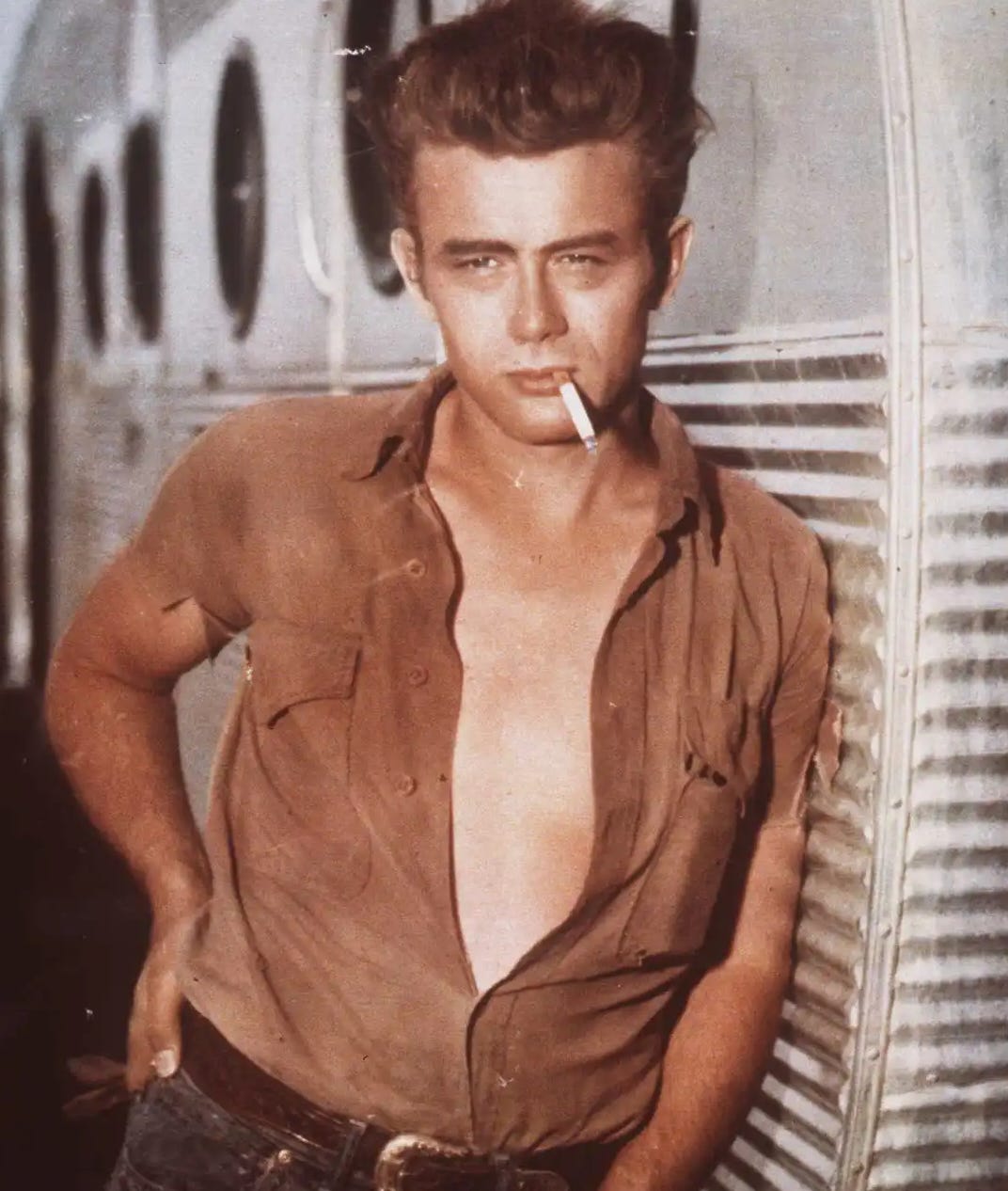

You know who looked way cooler than you’d expect a Quaker-raised boy from Marion, Indiana to look? James Dean. Good looking guy, James Dean. I’m not sure if anybody’s ever pointed that out before. Wavy hair. Sideburns. Great facial expressions– was he mad? About to cry? Interested in making out with you? Probably all of the above! And the leather jacket. We don’t talk enough about how hard it is to pull off a leather jacket.

It brings me no joy to share this, but you know how else still looks cool? Tom Cruise. Pretty complicated, guy, that Tom Cruise. Definitely somebody who is aiding and abetting the actions of an actual cult. Very likely somebody who would benefit from a more reflective relationship with masculinity and body image (Tom, you’re in your sixties! It’s okay to look like you’re in your sixties! And I appreciate that you can do your own stunts, but that doesn’t mean you have to!). But yes, he looks cool. He too can pull off a leather jacket.

Tom Cruise and his leather jacket are currently co-starring in a blockbuster movie about spies who wear masks and jump out of airplanes, but I want to talk about their blockbuster movie from last year. That one was called Top Gun: Maverick. I’m almost certain you’re familiar with it. I suppose I could have written about the original Top Gun, a movie from 1986, but I chose to focus on the sequel for one reason and one reason only.

This bears repeating. Top Gun: Maverick features a scene where a character named Maverick throws a flight manual in the trash can. It’s a really good scene. When I saw it for the first time, I literally thrust my fist in the air as if I had just won an NBA championship.There are a lot of scenes like that in Top Gun: Maverick. Here is a truncated list of activities that the film’s protagonist (Pete “Maverick” Mitchell, played by Tom Cruise and his leather jacket) engages in over the course of its run time:

-Disobeying his superiors when they tell him not to fly his jet too fast.

-Pretending that his in-flight radio is broken when his superiors attempt to scold him for flying his jet too fast.

-Riding a motorcycle affixed with a “Can’t Drive 55” sticker, a bold protest against a federal law that has not existed for decades.

-Sneaking in through a window in order to fool around with his love interest, even though both he and his love interest are very much fully emancipated adults.

-Repeatedly flying airplanes in ways that are a danger to both himself and his students.

-Being thoroughly annoyed when anybody suggests that he not be allowed to do whatever the hell he wants, whenever the hell he wants to do it.

In case it’s not clear, Maverick is a bad boy, a rebel. That’s not the interesting part, though. What’s most fascinating (and most honest) about both Top Gun movies is what our hero is rebelling against.

Maverick is an older White man, whose talents are well recognized by everybody around him. He has a long history of ruffling the feathers of the Navy brass, but he is able to maintain positions of leadership and authority because of old friends in high places. Top Gun: Maverick finds our hero being called in one last time for a high stakes teaching gig. He is the only person on the planet capable of training a new cohort of crack pilots to save democracy by doing rad jet stunts. The only complication (besides some legitimately emotional business involving prematurely deceased fathers and understandably resentful sons), is that, well, Maverick is a Maverick, and his employer is the U.S. Navy, and come on, man…. are you gonna expect Maverick to put up with all these squares?

Now, there are lots of justified reasons to rebel against the United States Military Industrial Complex, as well as a long tradition of enlisted soldiers and sailors questioning both macro and micro aspects of America’s military legacy. None of that is of any concern to Maverick, though. Our hero defies his superiors and generally acts like a petulant child because he’s concerned that the U.S. Navy is not good enough at being a frightening death engine. He’s not raging against the machine. He’s raging to make the machine more machine-like, to make it even better at wreaking havoc on a shadowy, unnamed (but come on, definitely Middle Eastern) enemy.

God, what an incredible plot. It’s such an honest, unsparing look at a very real race and gender dynamic that it’s surprising that it hasn’t been banned by the state of Florida. Our White male hero feels aggrieved and put upon, not because societal power dynamics need to be upended, but because they need to be reinforced. He’s mad as hell and he just can’t take [the most powerful military in the world not being even more powerful] any more.

This is not a new story, of course, and it’s hidden in plain sight throughout pop culture. White male characters always get to be the iconoclast, the rebel. That’s particularly true for those of us who have the smallest obstacles in our life against which to rebel. We’re the prep school Deadheads, subsidizing our hippie sojourns with trust fund support. We’re the “bad boy” stockbroker anti-heroes of Wall Street and Wolf of Wall Street. We’re Holden Caufield, calling everybody else a phony. And we’re James Dean, whose breakthrough performance was literally called “Rebel Without A Cause.” Do you know what James Dean’s knife fighting, Griffith Observatory-loitering, hot rod racing miscreant was rebelling against in that movie? The fact that his wimpy father wasn’t more of a tough alpha man!

You don’t have to squint hard to see the political parallels here. There’s a short walk from brooding Hollywood hunks like young Marlon Brando responding to the question “what are you rebelling against?” with “what have you got?” to crowds yelling “Build that Wall!” or “Don’t Tread on Me” and cops with Punisher tattoos. And while Hollywood’s version of the White male rebel is more likely a case of art imitating life than the other way around (after all, who were America’s Founding Fathers if not privileged aristocrats who fancied themselves bad boys), it’s all the same nonsense.

The easy, self-congratulatory version of this essay would end there, with me merely stating that White guys— Maverick, James Dean, Donald Trump, myself— love to cosplay as aggrieved rebels while still reaping all the benefits that our societal station affords us. You don’t need a newsletter for that, though. We are blessed to live in an era where that point has already been made by a wide range of bumper stickers. “When You’re Used To Privilege, Equality Feels Like Oppression,” “May You Have The Confidence of a Mediocre White Man etc. etc. etc.”

What I will say— both as somebody who is used to privilege and who possesses more confidence than his mediocrity merits— is that oh buddy, do I ever understand the appeal of playing the rebel. You see, I am not cool in any traditional sense. I look decidedly frumpy in a leather jacket. But I am a human being with an often contradictory set of emotions, insecurities, and knee-jerk reactions. I have, as we all have, solid evolutionary reasons why I crave both belonging and recognition of my individual specialness. I want to be both safe and noticed. I want to stand out just enough so that I can be assured that others are impressed by me, but not so much that I risk group rejection.

Like all of us, I bring these contradictory impulses (and so many more) onto a strange, confounding and by no-means-equitable playing field. I am sometimes capable of recognizing that the game I’m playing is rigged and that I am advantaged in it. Or, I should say, I’m capable of doing so until my own needy and extremely deafening interior monologue takes over. Then all bets are off.

As long-time readers of this newsletter know, I spent over a decade working at Teach For America, a relatively large education nonprofit. While there, I was fairly compensated, offered multiple promotions, and trusted with a number of intellectually challenging leadership roles. I worked with colleagues whom I both respected and admired. As was the case with every institution that I’ve been a part of, my experience there would have been significantly more difficult were it not for my multiple privileged identity markers. It was an extremely easy place to be a straight cis White neurotypical guy with a college degree.

It was also, for the record, a job. And like all jobs, there were good days and bad days— days when I felt seen, heard and recognized and days when I felt cast to the side. At times, I felt deeply aligned with the organization’s mission and direction. At other times, I was convinced that the whole enterprise was going to hell and I was the only one smart enough to see what was wrong. Some of my critiques were likely spot on, others were assuredly just projected insecurities.

Put differently, for over a decade I honestly aspired to be a model colleague— somebody who cared about his co-workers more than his own spotlight and who sincerely wanted the organization to be the best possible version of itself. Sometimes I pulled all that off. Other times, I was the Rebel Who Desperately Hoped He Had A Cause. I didn’t pop any wheelies in the parking lot, nor did I throw any instruction manuals in the trash. I practiced my rebellion in what I thought were more subtle ways— assuming that protocols and processes didn’t fully apply to me, talking loudly and frequently (often directly over women), gossiping and commiserating with any colleagues I could find who would validate my pre-conceived narrative.

If you had asked me— during my non-contiguous bursts of workplace-adjacent rebellion— if I recognized how comparatively privileged I was, I would have agreed with you vociferously. I told myself that none of my self-aggrandizing behavior was about me. I was doing it for our mission. I was doing it for the cause of educational justice. I was doing it for the kids, damnit.

The problem wasn’t my ignorance— it wasn’t that I was unaware of the decent lot I had drawn in life. Nor was it that I just didn’t care about my colleagues. The problem was simply that I had bought into the story of the cool rebel and therefore couldn’t see that it was exactly that— a story.

One of the most fascinating aspects of both Top Gun movies is how dream-like they are. They’re set on a San Diego military base that feels detached from time and space. The enemies are imaginary. The world outside of the base isn’t real. Over time, new classes of recruits become more diverse than their predecessors, but they still go to the same bars and party to the same classic rock hits. Another name for a dream is a fairy tale. And fairy tales aren’t just stories— they’re stories that exist for a specific reason.

I don’t want to pretend that I’ve arrived at a perfect moment of self-awareness, one where I will never again make other people answer for my insecurities. What has changed over time, though, is that I’ve gotten a more curious about why I’ve long gravitated to a particular variety of stories about myself. Who am I if I don’t get to play the rebel? What am I left with if I don’t get the comfort of believing that I’m smarter than everybody in my vicinity? What am I worth if all of my accomplishments weren’t earned fair and square ? And most importantly, whose stories did I miss because of the volume with which I told my own?

It took me far too long to notice what was missing from the stories I told myself. I partied hard at the tailgate in the parking lot, but never thought about who would have to clean up afterwards. I pumped my fist when Tom Cruise pulled off a death-defying stunt, but I ignored the size of the team that needed to be amassed to keep him aloft. I cared a lot about the moments I felt least secure, and very little about how anybody around me was doing.

Lord knows it’s fun to be a rebel, especially when you never have to live with the consequences. It’s an absolute blast to push your jet past mach nine and to rip it up on the weekend with your buddies from No Shoes Nation. But movies only last a couple of hours, and despite what we’ve been told, it can’t actually be five o’clock somewhere all the time. All that’s just another fairy tale we tell ourselves, just like the one about the cool iconoclast who is never wrong and never grows old.

Song of the week:

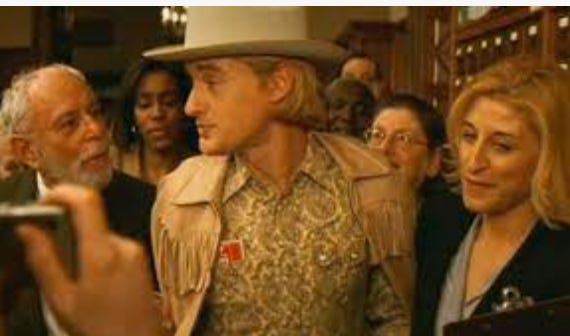

Eli Cash in The Royal Tenenbaums voice:

“Everybody knows that the best Kenny Loggins song from he original Top Gun soundtrack is ‘Highway To The Danger Zone’ but what this essay presupposes is '…What if it’s ‘Playing With The Boys?’”

As always, the entire Song of the Week playlist is available on Apple Music or Spotify.

CORRECTIONS AND OMISSIONS DESK: In my original draft of this essay, I said that Kenny Chesney had been married to Reese Witherspoon. That is incorrect. He was once married to Renee Zellweger, a completely different human being. Although both women are acclaimed actresses who came to fame at around the same time, they are not the same person and come on their names aren't THAT similar. It won't happen again.

Wow. This one sentence stands out above all the others in this excellent essay: "And most importantly, whose stories did I miss because of the volume with which I told my own?"

Something we all need to think about.