Stone Throwing Day at Glass House County Schools

The White Pages Collegiate Academy For Allegorical Scholars

A quick note: I use “we” a lot in reference to white people in this particular issue. That’s not to infer that only white people read this newsletter; it’s just an attempt to include myself in the community that I’m critiquing.

I don’t remember the first time a person of color or an Indigenous person confided in me about how much other white people sucked, but oh-my-goodness I can tell you how it felt. You hear a lot about white people being desperate for affirmation from people of color, but man, for me the quest for praise isn’t nearly as addictive as the narcotic drive for some good old fashioned closed-door gossip.

I can definitely recall a period of time— while I was working at a very large traditionally white organization and was becoming more vocal about anti-racism— when the volume of these conversations really ramped up. And friends… I lapped them up.

If you had asked me back then whether or not I had an unhealthy relationship to the various tidbits of gossip that I was receiving, I’d have denied it. And I wasn’t, you know, consciously lying. I truly thought that I was receiving all of this information with the appropriate spirit of pursed-lipped Very Serious Ally-ship.

That’s a load of hooey, though. In reality, even the slightest hint that a few people of color or Indigenous people might have declared me safe enough for commiseration caused me to be all sorts of weird. Rather than focusing solely on being present for my friends and colleagues, I took subconscious pride in what this access proved about me. It allowed me to tell a story of shared intimacy, of what a Good White Person I Was. It allowed me to fool myself into not thinking that, in other moments, those same people didn’t have to still commiserate with others about how much I sucked, too.

Of course, this isn’t JUST a problem I’ve had vis a vis conversations around race. My greatest regret from my twenties and thirties in general is over the amount of friendships and professional relationships that I made about me— how much comfort they gave me, what kind of person they revealed me to be etc.— rather than actually being present for what the other person needed.

I also know, though, that I’m not the only white person with this problem.

There is no objectivity in biweekly newsletter writing

Because I worked in education for over a decade, the vast majority of you are still in that world. Many of you work for charter schools. Others work for district schools or unions. Even more of you Have Opinions On This Stuff.

This issue isn’t really about charter schools— I could have used any political fight as an allegory. But, I do go deep into debates over charters so, in the spirit of not hiding the ball, here’s where I’m coming from (be forewarned, it’s not particularly sexy or incendiary): Political-philosophy-wise, I’m a Nordic-style socialist. I like government programs to be as universal as possible (unionized, centrally managed for equity, free at the point of use and with the same stuff being utilized by all folks together across racial and class lines). This is half because I’ve lived in a country where there was more of that sort of thing (and it ruled!) and half because I’m a Quaker (and taking care of everybody is kind of our deal).

That’s to say that if I was building America’s education system from scratch, I’d lean less on “giving parents more choices” and more on “ensuring that the single public school system that all students attend was amazing for all kids.” In general, I want a populace with fewer consumers and more neighbors. And yet, our weird American obsession with “parents as school shoppers” wasn’t started by Black and Brown parents at charter schools; it’s the sui generis creation of generations of white parents with means (see: suburbanization, magnets-and-selective-enrollment schools, private schools, steroidal white PTA fundraisers, etc.). I get why Black and Brown parents would be pessimistic about the ability to undo that more insidious web of segregation-enhancing parental choices and instead say, “Listen, the system as a whole isn’t changing. I just want a piece of it that works for me.”

So that’s where I’m at right now. I’m neither a true believer in charters nor a bomb-thrower against them. I also don’t think that either chartering more schools or banning them all tomorrow is going to stop the larger trends that build and maintain separate and unequal education systems.

If you’re looking for a fascinating petri dish of racial politics, though, holy cow, the discourse around charter schools is a fully stocked laboratory.

Clowns to the left of me, jokers to my right

As hinted above, Black, Latinx, Asian, Middle Eastern and Indigenous folks make a wide variety of strategic choices about the kind of schools with which they align themselves (be they as parents, educators or leaders). These include, but are by no means limited to: Ideological affinity for either market-based or centralized solutions, execution of a broader theory of change (eg. tribal sovereignty, Black autonomy, etc.), distrust of the U.S. government (particularly because of institutional racism), distrust of the free market (again, usually because of institutional racism), terrible experiences in district schools, terrible experiences in charter schools, wonderful experiences in either of the same, desire for experimental educational models, effective (and/or duplicitous) marketing, social influence, generalized fatigue and/or hopelessness.

The key modifier there is “strategic.” One mistake that white people often make when we find themselves in political or professional affiliation with people of color is mistaking coalitional common interest for a personal endorsement. We fail to recognize the sophisticated maneuvering that communities and individuals have to make in a country that wasn’t built for them. Just because Black and Brown folks are working with us doesn’t mean we’ve arrived. Often, it just means that we’re at least temporarily the lesser of many evils.

White people also have a wide variety of strategic reasons why we align ourselves with different educational institutions. I’ve never known anybody who has landed on either side of the debate in bad faith.

There is an interesting thing I’ve seen us do, though, once we pick our team: We become quite pleased with ourselves for having picked correctly, for having chosen the side without all of the racists.

Of course, there’s a lot of weird, thirsty psychology at play here, but to our credit, it’s not like our self-righteousness is without evidence. If you’re worried that this was about to become a staid “fine people on both sides” bromide, don’t worry— there’s plenty of bad behavior all around.

Is it true, for example, that for too long the charter-school-philosophy-du-jour was a “no excuses model” that was at best draconian and at worst dehumanizing to students of color? Oh, for sure.

Is it also true that most major district teacher’s unions are good at racial justice rhetoric, but aren’t particularly urgent about racist teachers in their rank-and-file? Yep, that too.

Are a lot of major charter school organizations bankrolled with money from people and institutions that haven’t been true partners in Black and Brown communities? Oh, absolutely. Is it also true that most charter school opponents focus their energy disproportionally on the choices that Black and Brown parents are making, but not the much larger ways that white parents segregate and drain Black and Brown schools of resources? Yep. Are charter school opponents perhaps too fast to dismiss anything strong happening in individual charter schools as just smoke and mirrors, and therefore miss opportunities to learn from them? Oh, totally. Can their proponents be too quick to accept the destruction of Black community institutions as collateral damage when neighborhood schools (such as in Chicago) are closed and a predominately Black teaching force is fired en masse (as in New Orleans)? Also yes.

Now, to be fair, are there people on both sides of the debate trying to do the hard internal work of fighting for justice— both in their “sector” and more broadly? Undeniably. I’m just saying— none of us have arrived anywhere close to the promised land yet.

Big Structural Ballyhoo

Recently, there was a dust-up at the public discourse corral. You may have heard about it. Senator Elizabeth Warren, Presidential Candidate and giant inflatable dog deployer, held a rally in Atlanta. Black parents and grandparents protested it. The activists, who supported charter schools, were opposed to a handful of charter-phobic planks in Warren’s education plan. They were escorted out, but Warren met with them afterwards. While dramatic, none of it seemed out of the ordinary for an election cycle. Candidates have a right to take stances. Activists have a right to voice their support or opposition to those stances.

But that’s not what happens when there is a Bigger Fight To Be Had. And so, it has come to pass that, in the days since the initial protest, ink has been spilled by both sides of the grand charter school debate, each one labeling the other the true racists.

Here’s a partial list of the attacks that have been volleyed around: Warren has been harangued as a hypocrite who sent her son to a private school, the parents were scolded for receiving Walton Foundation funding, those scolds were in turn taken to task for focusing more on the Black parents’ funding than on the white advocacy groups’ ties to billionaires. The New York Times weighed in, noting that Black folks have a wide variety of view on charters. This then led to a response from charter school critic Diane Ravitch about how Black anti-charter activists are the “real civil rights leader[s].” Elsewhere, pro-charter supporters feted Sarah Carpenter, the organizer of the Warren protest, as a modern day Harriet Tubman and Rosa Parks and threatened to leave the Democratic party for disrespecting her. Anti-charter folks shot back that the NAACP is against charters and Betsy Devos loves them. Somewhere, on some corner of the internet, the dust-up is likely still raging.

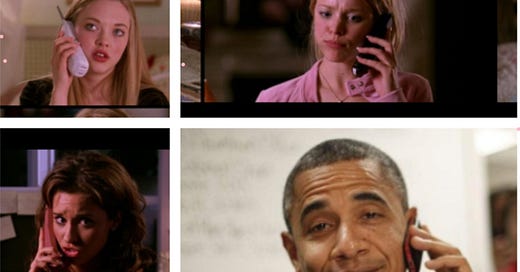

I have no quarrel with the Black folks engaged on this debate— they’re speaking for themselves (I appreciated this interview with one of the protesters, Dr. Howard Fuller). There’s just something about the way that virtually every white person has weighed in on this fight that has left the worst taste in my mouth (and just to be clear- the vast majority of the pieces linked to above were written by white people). When both sides continue to point to the same Black and Brown leaders who agree with them, projecting a fictively monolithic community consensus onto those voices, it feels less like ally-ship and more like a quest for absolution-by-association.

Listen, I’m not saying that, when you’re in a political coalition, it’s wrong to elevate voices of color from inside your tent. And if you truly believe that there is an other side standing in the way of justice, then by all means, harangue away. Let’s just not get carried away with thinking that our field must smell like roses just because we’ve got evidence that our neighbor’s stinks like manure.

Every time a friend has taken me aside and asked for sympathy and support with other white people, they’ve wanted something pretty simple— sympathy, a listening ear, love. They weren’t saying “Garrett, you’ve got nothing to work on, racism-wise” or “Garrett, I hope you feel pretty good about what a great white you are.” And every time I’ve unintentionally projected any of that other junk onto the scenario, I’ve failed to be a friend. I made it about me.

Likewise, if your elevation of Black and Brown voices in your professional or political networks is primarily designed to show how racist other white people are, then you’re not really interested in being a friend or coalition partner. You care about them because of the story they allow you to tell about yourself.