Top notes:

Thanks, as always, for considering upgrading to a paid subscription. For more context on how I think about earning a living (and asking for your help in doing so), I put together a little document here that you might enjoy reading.

Another quick note: Want a playlist of every song mentioned below (plus others that fit the theme)? Let’s do it: the Apple Music version is here and the Spotify one is here (I had to do some creative swaps with the Spotify edition, for Neil Young-based reasons; you get the gist, though). Enjoy!

This list— like all truly great things— is a result of procrastination. As long-time readers know, I’m currently writing a book. It was once called Race of Strangers but is now called The Right Kind of White. It’s had a lot of titles, actually. By the time all of this is said and done, maybe it’ll be called EveryWhite Everywhere All At Once. It is a memoir that (I hope!) will have something helpful to say about this moment in time in Whiteness (and in particular, about White America’s relationship to itself). I am thoroughly enjoying writing it, though I also frequently enjoy avoiding writing it.

To be fair to myself, it isn’t exactly procrastination to be thinking about Whiteness in song in the moments that I should be writing. Culture! It matters, as it turns out! Particularly when it comes to understanding group and individual identity formation! Reflection and refraction, a mirror and a window, etc., etc., etc.

That can be true and it doesn’t change the fact that the line between “useful research” and “gratuitous rabbit hole” is tissue-thin. It’s just that the more I thought about White popular music, the more I noticed a trend. There are plenty of songs by White people that comment on race and/or racism, but very few that are self-aware about their own Whiteness. If you’ve ever read Toni Morrison’s Playing In The Dark, you’re likely noticing the literary parallel here. White artists are haunted by other people’s Blackness or Brownness, and are pretty good at noticing the flaws in other White people’s presentation of their Whiteness, but are very rarely self-conscious or self-examined about their own Whiteness. And that’s interesting! Interesting enough, at least, to distract me from book writing.

So, in honor of that rabbit hole, here is a list of ten songs that (taken together) tell a fascinating story of 20th and 21st Century North American Whiteness. And no, they don’t all pass the “self-aware and self-examined” test. But those that fail it do so in a deeply interesting way.

The title, by the way, is either an homage to or a direct rip-off the truly excellent podcast “60 Songs That Explain The ‘90s.” You’re allowed to be impressed by my relative efficiency, though. Only ten songs!

“Alabama” by Neil Young

“Sweet Home Alabama” by Lynyrd Skynyrd

The Ur-Texts! The alpha and omega! Perhaps the most honest expressions of the forces animating contemporary White politics ever put to song. The first blow is the emotionally simple one: A White liberal from the North Country (in this case, the literal North Country, Canada) feels badly about racism and decides to shoot a few fish in a barrel. It’s not that he's wrong. He picks some pretty loathsome targets (the Klan, George Wallace). But his tone is alternately sneering and paternalistic:“Alabama, you’ve got the rest of the Union to help you along. What’s gone wrong?” In retrospect, it’s not surprising that his volleys (both in this song and its twin polemic, “Southern Man”) inspired more defensiveness than sober self-reflection from its targets.

The most notable defensive reaction, of course, came from Lynyrd Skynyrd, a bunch of buddies from the part of Florida that’s not-technically-Alabama-but-is-spiritually-aligned-with-Alabama (also known as “Jacksonville”). I’ve written about “Sweet Home Alabama” already, but I’ll continue to think about it until the day I die. A rich text, that one. Like all defensive reactions, it’s much more emotionally complex (and rhetorically muddy) than the stimulus to which it’s responding. Its own co-authors have posited a wide variety of explanations as to what it’s all about. Is it a defense of good-ole-boy Southernness (“In Birmingham They Love The Governor”)? Or a subversion of it (“Boo, Boo, Boo”)? Were the Confederate Flags on stage ironic or earnest? Is this a song about imagining a New South or holding on tight to the old one? Was Neil Young really a pallbearer at Ronnie Van Zant’s funeral? And what about the cover of the Street Survivor album?

“Sweet Home Alabama” will always be a mystery box because the way the human brain processes cognitive dissonance isn’t fully linear or cogent. All we know is that being looked down upon triggers something deep down in our collective psyche. The person judging us may be right. We may very well be as awful as they contend. We may even feel that guilt and culpability in our more private, honest moments. But what matters is that they don’t get to say that, damnit. They don’t know us. And even if they do, they’re a bunch of hypocrites anyway. And so we’ll write a reaction song. We’ll make it way catchier than the tune to which it’s responding. Our song will end up on a license plate. Our song will be played in sports arenas. Our song will show them.

Turn it up, indeed.

[Honorable mention: “Okie from Muskogee” by Merle Haggard and “The Three Great Alabama Icons” by Drive-By Truckers, which is about the Young/Skynyrd dynamic, the political transformation of George Wallace and “the duality of the Southern thing”].

“Rednecks” by Randy Newman

“I Believe The South Is Gonna Rise Again” by Tanya Tucker

We do have a couple of other moves, us White people— ones that fall somewhere in between the White liberal’s guilt-ridden deflections and the reactionary defensiveness they inspire. One of the more popular ones, particularly for the smarty-pants amongst us, is world-weary cynicism. A pox on all y’alls houses, if you will.

Rednecks is a particularly skilled entry in that emotional genres— arch and caustic and factually accurate, but also much too pleased with itself. Sure, Newman’s bigoted Southern narrator is correct in pointing out that he’s one hell of a racist, but so too are his compatriots in the North. He’s correct in tying a rhetorical thread between Atlanta and Boston. I’m just not sure what is accomplished by it other than a grad-school-friendly excuse for a White singer to say the N-word a bunch.

I’m not trying to pick on Newman here. “The Beehive State” is an all-timer song about White American myth making. It’s just that I’ve pulled the “Rednecks” move a ton in my life (not the “creating a character through which I can sing the n-word" move, mind you, but the “pushing-up-my-glasses-and-waving-my-finger-and-saying ‘what if I told you that ALL White people are racist!’” move) and, while it was more trenchant when Newman did it in the 70s, it’s long since grown tired. In the year of our Lord, 2023, it’s just another form of absolution seeking, a little more subtle than what Young and the Skynyrd boys were up to, but still. Don’t blame me, I voted for critical analysis!

You know what we could probably spare to do a lot more, though? Whatever Tanya Tucker is up to in “I Believe The South Will Rise Again.” I’m sure that there’s points on which it can be criticized: it might be a little too treacly, a little too kum-ba-yah-ish. Perhaps, God forbid, it commits the worst of all contemporary sins: being cringey. But it’s brave enough to actually be hopeful, to actually believe (for instance) that White people (and poor White people especially) could be a part of a multi-racial coalition. And that doesn’t make it any less clever or subversive (the title!). But it’s lovely in its overwrought earnestness.

“A brand new breeze is blowing 'cross the southlandAnd I see a brand new kind of brotherhood.”

Put that on a license plate, damnit.

[An honorable mention which was not included solely because I arbitrarily chose to limit this list to“North American” tracks: “White Man In Hammersmith Palais” by The Clash, which splits the difference between know-it-all pontificating and heart-on-its-sleeve earnestness].

“White America” by Eminem

“White Privilege Part II” by Macklemore

“Clap Back” by Iggy Azaelea

Dearly beloved, we are gathered here together, as was inevitable, to discuss White rappers. Before we do so, let me pause and implore you (not for the first time in this space) to read my favorite essay of all time— “The White Rapper Joke” by Hanif Abdurraqib (from They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us). It is both brilliant and includes far more discussion of both 3rd Bass and Bubba Sparxxx than I have space for here.

More broadly, though: God bless the White rappers. Each of these songs is nominally about being White, although in the most self-conscious way possible. What they’re really about is noticing that you’re White in a space that is not supposed to be for White people, but which you would like to remain in. It’s about justifying your right to declare yourself down and profit from your downness. As a former White nonprofit Executive Director who wrote multiple “listening and learning” emails, I see you, White rappers, I see you.

The easiest way to understand the difference between these songs (and, more broadly, to understand the White rapper identity in general) is by using an earnestness/perceived corniness taxonomy. Eminem, for example, hears your criticisms about cultural appropriation and basically laughs them off. But because he is traditionally perceived as having the chops, connections and working class authenticity to qualify as a “real rapper” his “hahahaha whatever… I’m White- deal with it!” tone is excused more often than not (see also: the myth-making in the climatic battle rap scene in 8-Mile). And maybe that’s fair. Class matters. The other rapper in 8 Mile “went to Cranbrook.” I’m not sure if you’ve heard, but “that’s a private school.”

Meanwhile Iggy Azalea adopts an equally arch, “screw the haters” tone, but can’t escape the “corny” tag. The rub on her is that she’s a wanna-be without the requisite skills or back-story to earn respect. That may be due to her gender or a U.S.-centric hip hop bias (she’s Australian) or it might be that she is in fact a corny and unskilled rapper. Competence matters in these affairs, but competence is also in the eye of the beholder (and there are patterns as to who most frequently gets to be the official beholder).

So where, then, does that leave Macklemore? My goodness he’s earnest. And you know, per our earlier Tanya Tucker discussion, that I have a soft spot for earnestness. We’re often taught to distrust it, though. The worst thing a White person can do is to make it obvious how hard we’re trying.

And my goodness if Macklemore isn’t trying. In the nine-minute-long (!!) White Privilege II (his second song on the subject), he is humble to the point of self-ridicule. He rattles off so many anti-racist correct answers in a short space. He even takes a carefully choreographed “listening and learning” seat in his own song, deferring more than once to Black artists. It is immensely tiring in that way we (earnest White liberals) are so frequently immensely tiring. He’s trying to do the right thing! He wants you to see him doing the right thing! Unlike Iggy Azalea, there’s no question as to why Macklemore is derided for corniness: He’s a White liberal publicly trying, which means he’s an easy butt of jokes for the equally-earnest amongst us. If we mock Macklemore’s corniness, perhaps we’ll get a pass on our own. Just the other day, I made a joke on Instagram about a Swedish singer who recently performed in that country’s national song contest wearing a jacket that looked like it had fake graffiti on it. I said he had “Scandinavian Macklemore vibes.” I wasn’t wrong, but also… what did Macklemore ever do to me?

What I’m saying is that if Macklemore didn’t exist, we’d have to invent him. Or else we’d just make fun of another publicly earnest White person.

Also, his new album’s got some fun tunes on it.

[Honorable mention: “Pop Goes The Weasel” by 3rd Bass, “In The Ghetto” by Elvis]

Coal Miner’s Daughter by Loretta Lynn

the last great american dynasty by Taylor Swift

Cowboy Dan by Modest Mouse

None of these songs contain the word “White” You could argue that they don’t address Whiteness directly at all. But it’s precisely for that reason that they each have something interesting to say about a particular subset of American Whiteness (in this case, Appalachian poverty, New England WASPishness and High Desert Western alienation).

These are stories about gender and class that are unique to specific White micro-communities and, as such, have something more interesting to say than the omnipresent Whiteness-noticing-itself triumnverate: (“I feel guilty for being racist,” “I don’t feel guilty at all; how dare you call me a racist” and “Look at how well I can judge other White people”).

“Why, I've seen her fingers bleed

To complain, there was no need

She'd smile in mommy's understanding way”

“Her saltbox house on the coast

Took her mind off St. Louis

Bill was the heir to the Standard Oil name and money

And the town said, "How did a middle-class divorcée do it?"

“Cowboy Dan's a major player in the cowboy scene

He goes to the reservation, drinks and gets mean

He didn't move to the city, the city moved to me

And I want out desperately”

You see? Those are three interesting, self-contained stories, simultaneously sympathetic and worthy of interrogation and prodding. And, yes, they would benefit from even more curiosity about the ways in which race shows up, but that’s the gift of great, self-aware storytelling— it invites more questions. Why did Loretta Lynn’s mother feel “no need to complain” given both the precariousness of her family’s situation and the daily indignities she faced each day? What would have been the risk of complaining? What would have been gained and lost? To whom was she comparing herself when she counted her relative blessings?

I could go on. I have so many questions about Taylor Swift’s Rebecca (“How DID a middle-class divorcée do it? And what did she gain and lose in the doing?”) and Isaac Brock’s Cowboy Dan (“What do you lose when the city comes to you? And what about the reservation makes you turn in that direction when your life is out of control?”). Heck, I could spend a little day on follow up questions about that other line in that song (“He goes to the desert, points a rifle at the sky and says ‘God if I have to die you will have to die!’”).

Just to be clear, I’m not of the opinion that these last few entries are the “good” songs about Whiteness and the first seven are the “bad” songs. They’re all interesting, and they’re all telling.

What’s most notable is the dynamic— in all of these songs— between when and why Whiteness is rendered consciously and when and why it is ignored. I am fascinated by the narrow box we put ourselves in, as White people, when we Officially Notice Whiteness. It is so limited by self-consciousness and script-following, so flat and uni-dimensional. And that’s precisely what makes it so interesting. To what end do we deploy this faux-flatness? What comfort are we seeking when we cling to such narrow narrative threads? What are we hiding? And more importantly, what do we lose: in the stories we don’t tell, the questions we avoid answering, the moments when the “what does this say about Whiteness?” should be the melody, but is shoved as far down the mix as possible?

[Honorable mention: Oh, so many, many of which have shown up on White Pages songs of the week over the years— “Twin Falls” by Built to Spill, “April the 14th Part I by Gillian Welch, “American Teenager” by Ethel Cain; “Tournament of Hearts” by the Weakerthans. I’ll stop, though the playlist has many more]. And of course, feel free to pitch potential additions in the comments!

End Notes:

No song of the week this week, for obvious reasons. But here, again, is that playlist (Apple Music here; Spotify here, although with the Neil Young caveat I made in my top note).

Adding this to the conversation re: Merle for the folks who haven't listened

https://cocaineandrhinestones.com/merle-haggard-okie-from-muskogee

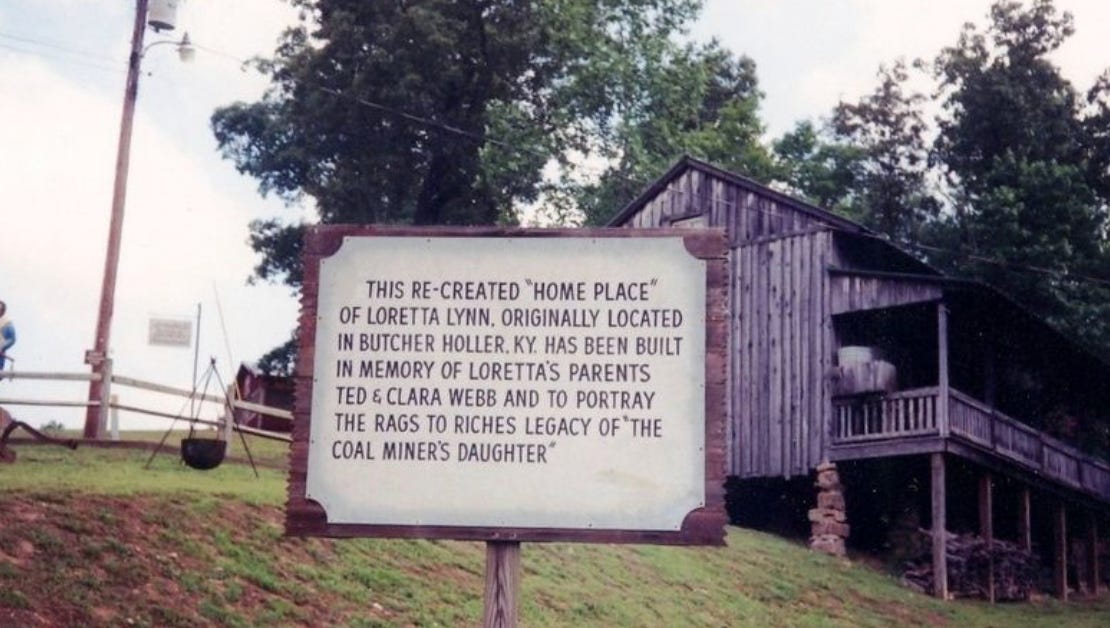

Garrett! Have you been to Loretta Lynn's "home place" as pictured here? I went there with my dad once, many years ago. It was an intensely weird experience for two reasons:

1. It is a little museum of romanticized past rural poverty, surrounded by normal contemporary rural poverty

2. Partway through the tour it became clear from context clues that the dude giving the tour was her brother, whose job I guess it is to give tours of the the home he and his siblings grew up in.

Also can I inquire what you think "What's Yr Take On Cassavetes" says about whiteness?