"That's all I've got to say about that"

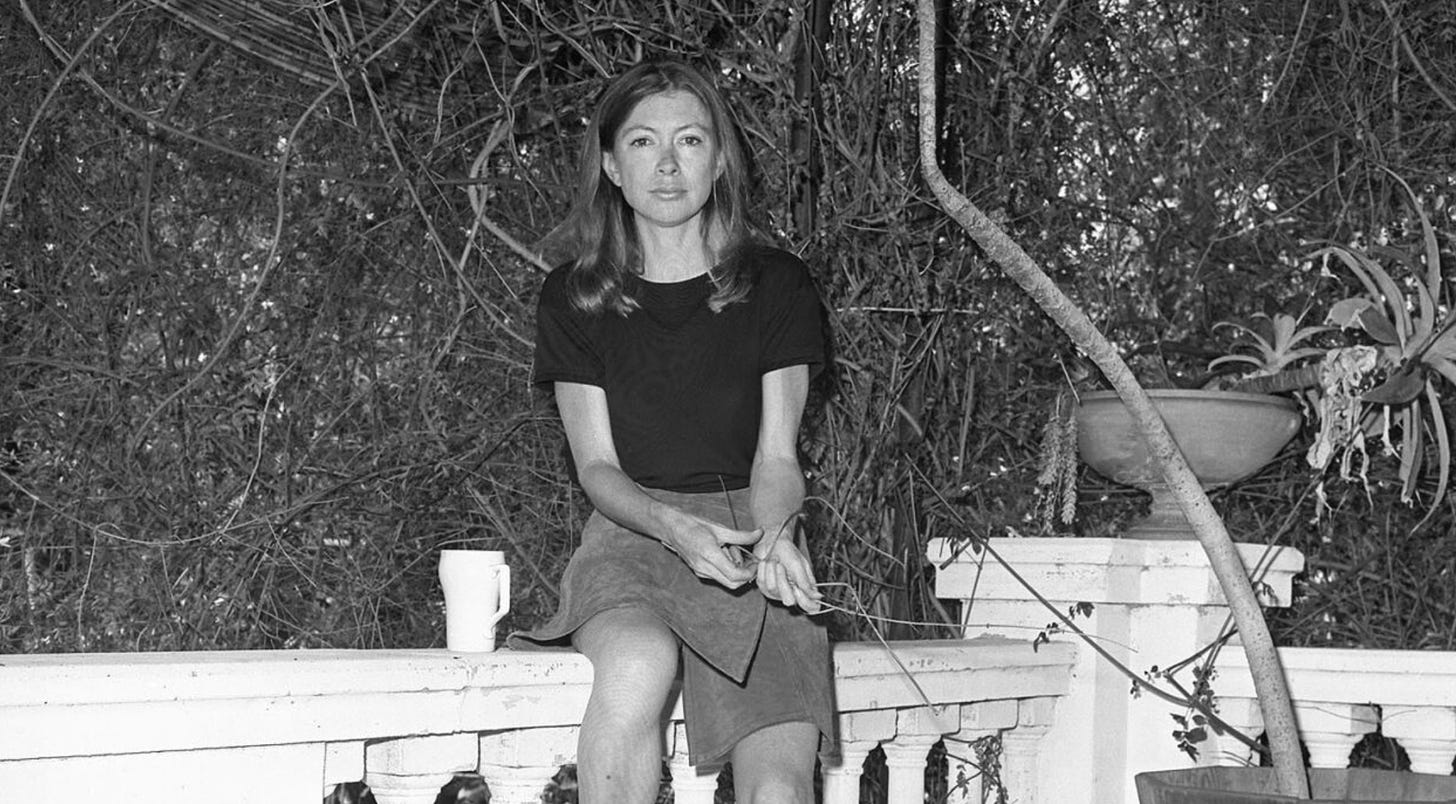

"10 Movies, 10 Stories of Whiteness Issue Two:" Forrest Gump, Joan Didion, and the privilege of sleepwalking through history

Welcome to the second edition of the “10 Movies, 10 Stories of Whiteness” series. You can find previous essays in the series here (and a reminder about what this is all about here). This particular edition is for paid subscribers, though with a pretty hefty preview for the free subscriber crew (love y’all too). While I hope that you’ll consider subscribing if you have the means (five bucks a month or fifty bucks a year), if money’s tight and you still want to read the whole thing, just email me at garrett@barnraisersproject.org and I’ll comp you, no questions asked.

Next week, we’re continuing the series with Dangerous Minds, a movie with one of the best Wikipedia summaries of all time (“[the students] immediately coin the nickname ‘White Bread’ for LouAnne, due to her race and apparent lack of authority, to which Louanne responds by returning the next day in a leather jacket and teaching them karate”). I’ll be doing a live watch/commentary on Thursday night at 8:30 PM Central Time over at the Flyover Politics Discord. If you’re a paid subscriber and are struggling with access to that space, let me know.

Do you know how many assassination attempts are depicted in Forrest Gump? Six! Jeez, that’s so many assassinations. JFK, RFK, George Wallace, Gerald Ford, John Lennon, and Reagan. That’s weird, right? No MLK, no Malcolm X, just six White men whose only common bond is that somebody once tried to kill them in public. Some of those assassinations stand among the most iconic moments in American history. Others have largely been lost to time [poor Gerald Ford, but nobody really talks about his (multiple!) assassination attempts anymore]. In Forrest Gump, though, every assignation— iconic or forgotten— is just one cog in a running joke: A newsreel image flashes on the screen, gunshots ring out, and Tom Hanks reflects in a molasses-paced drawl about how “somebody shot that man” for “no particular reason at all.” Hahahahaha. Assassinations! Crazy, right?

I didn’t notice the six assassinations when I first watched a VHS copy of Forrest Gump. I was sleeping over at my friend David’s house. We were 14, just a few months from starting high school. In retrospect, it was a transitional sleepover. Just a couple of years previously, a sleepover at David’s house would have meant a Super Mario 3 marathon, some generalized basement roughhousing, and eventually waking up to chocolate chip pancakes prepared by a bleary-eyed parent. That particular sleepover, though, we had put away childish things. We stayed up later, chose movies that felt decidedly adult, and made our own breakfast in the morning. We were now the bleary-eyed grown-ups, having spent the evening watching cinema and considering the human condition.

I remember having trouble sleeping that night. I replayed scenes in my mind as I squirmed in my hand-me-down sleeping bag. The film felt important. It was interested in mortality and the shape of a life, neither of which were topics that fourteen-year-old me had considered up to that point. I was particularly transfixed by the movie’s second act, after Forrest returns from Vietnam. That’s the film’s counter-culture section, where the soundtrack is filled with Creedence and The Byrds and Jenny drops acid and you get an Abbie Hoffman cameo. To think… in just a few years I wouldn’t be a gangly teen, but instead a hip young adult finding my voice, attempting to shape the course of history, and (hopefully) avoiding a mid-movie freak out where I listened to “Freebird” too loudly and considered jumping off a ledge. Far out. Scary as hell, but far out.

At the time, I assumed that Forrest Gump was an incredibly subversive film, mostly because it was the only major motion picture approved for suburban Maryland cul-de-sac sleepovers that included depictions of sex and drugs and radical politics. This is why we as a society probably shouldn’t look to neurotypical White teen boys to provide the bulk of our cultural commentary.

I hate to break it to fourteen-year-old-me, but Forrest Gump is not a very subversive movie. The standard consensus viewpoint these days is that it is not merely treacly and melodramatic, but reactionary and problematic.

The evidence for Forrest Gump’s conservatism is all right there on the screen. This is a film about a White Southern man whose developmental disability is played alternatingly as a punchline and as the source of some innate magical goodness. In spite of being named for LITERAL ACTUAL NATHAN BEDFORD FORREST (his mother’s choice of the KKK founder as a namesake is explained as being a reminder that “sometimes we all do things that just don’t make sense,” which is not typically how naming a child works), the movie’s hero is able to single-handedly transcend racism merely by being blithe, pleasant, and deeply interested in the shrimping industry. Forrest finds happiness and riches by following a virtuous path of clean-living and entrepreneurial capitalism. Meanwhile, his love interest Jenny chooses the path of sex, drugs and leftist cynicism— choices that leave her repeatedly abused, abandoned and eventually dead of AIDS.

So sure, it’s easy to write off Forrest Gump as merely being a conservative film. What’s more, its immense popularity upon release can be at least partially explained as being the product of the same sepia-toned Baby Boomer nostalgia machine that allows The Rolling Stones to sell out stadiums in perpetuity. It is a movie that depicts America as having been through some stuff together, but whose center can and will hold as long as you keep a smile on your face and your mother’s chocolate box-based-advice in your heart.

To merely discount Forrest Gump as a Republican boomer fantasy is to misunderstand that at its core, Gump is an American fairytale. And fairy tales may be easy to critique, but that doesn’t mean that it isn’t important to dig into what makes them so appealing.

At some point early in 2017, I started instinctually pulling Joan Didion’s The White Album off of my bookshelf. Sometimes I just re-read the first paragraph (the “We Tell Ourselves Stories In Order To Live” one), other times I’d finish the whole essay— re-tracing Didion’s steps as she travels from her house in the “senseless-killing neighborhood” to various late ‘60s locales: the Doors’ recording studio on Sunset, Huey Newton’s post-incarceration press conference in Oakland, Linda Kasabian’s jail cell in the Sybil Brand Institute for Women.