The choice that would actually make a difference is the only one that's never on the table

Notes on middle school open house

When you’re biking your son south on Martin Luther King Drive, everything changes at Walnut Street. Up to that point, the ride has been relatively flat, but as soon as you cross that too-wide intersection with its too-fast traffic, the slope is immediate, almost cliff-like. You’re pedaling fast now, faster than you intended, at what feels like a 45 degree angle. You’re zooming, speeding further and further away from Bronzeville, a once and future thriving Black business district destroyed by highways and hatred, currently rebuilding itself. If you let yourself glide all the way down the hill, you’ll be downtown, with its rowdy bars and glassy bank buildings and the fancy new arena that looks like a Jetsons spaceship. You’ll be in the part of town that locals are increasingly proud to show visitors. “Milwaukee’s a hidden gem,” your out-of-town friends assure you, after you take them to the Edison-bulbed food halls and the picturesque Riverwalk. It’s the old trick of municipalities— concentrate as much beauty and vitality in one spot and hope that nobody asks about what you’re not choosing to highlight.

You’re not going all the way downtown today, which means that you have to pull a tricky maneuver. You slam the brakes hard, working against your natural momentum, stopping yourself halfway down the hill. Your destination is one of the old Schlitz Brewery buildings, a cream-bricked monument to a time when this town was mostly German and at the red hot center of the American economy. Your son climbs out of your cargo bike’s back seat— he’s been quieter than normal on this trip. He perks up when he sees your wife biking up the hill towards you; she’s coming from her shift at the hospital that used to be called Mount Sinai but keeps getting swallowed up by wave upon wave of corporate mergers.

The three of you are here because your son is a fifth grader and, as such, has reached the end of his career at the little elementary school a few blocks from your house. You remember his first day of pre-k, when he clung to your leg and choked back tears when the principal asked him his name and one thing he loved (“trains,” he stammered back). At the time, you couldn’t imagine parenting could get any more emotionally devastating. You know better now. You’re here because you have a choice to make. You’re here because “having a choice to make” is what you’ve been told parenting is all about.

Starting in the 1990s, your city went hard for school choice as an education reform strategy. Thanks to all of this commitment to choice, you now have a fatiguing array of options— district, voucher, and charter schools in the city as well as open enrollment options into suburban schools— but what you don’t have is a clear feeder pattern from your home elementary school to a relatively close middle school. There is a middle school with which your bilingual elementary school has a special relationship— the “language” school— but that’s on the other side of town. Maybe you’re overthinking the distance. Maybe you’re using the distance as an excuse. Maybe you want to be courted and wooed by schools. Or maybe you’re just exhausted by it all and already want it to be over.

There are many ways to tell the story of how Milwaukee went so hard on choice. The most straightforward version is that we’re a large, mostly Black and Brown city that was hit hard by deindustrialization and other ravages of capitalism. This means, in turn, that we’ve been subject to no shortage of attempts— some more malevolent than others— to try to “fix” the problem of schools that exist at the end of so many funnels of trauma and oppressive systems. That world used to be your day job, it used to be your entire life. It looks different now that you’re a parent.

The more specific story is one of unlikely political bedfellows, one of whom was Milton Friedman. For Friedman and his fellow University of Chicago economists, education was a game with a clear enemy (large, centralized, unionized school districts) and a clear solution (laissez faire educational marketplaces). Friedman’s dream was universal vouchers— a world where large public school districts would cease to exist and parents would vote with their feet for the “best schools.” The end result, per Friedman, was that the “bad schools” would wither away thanks to various benevolently efficient invisible hands.

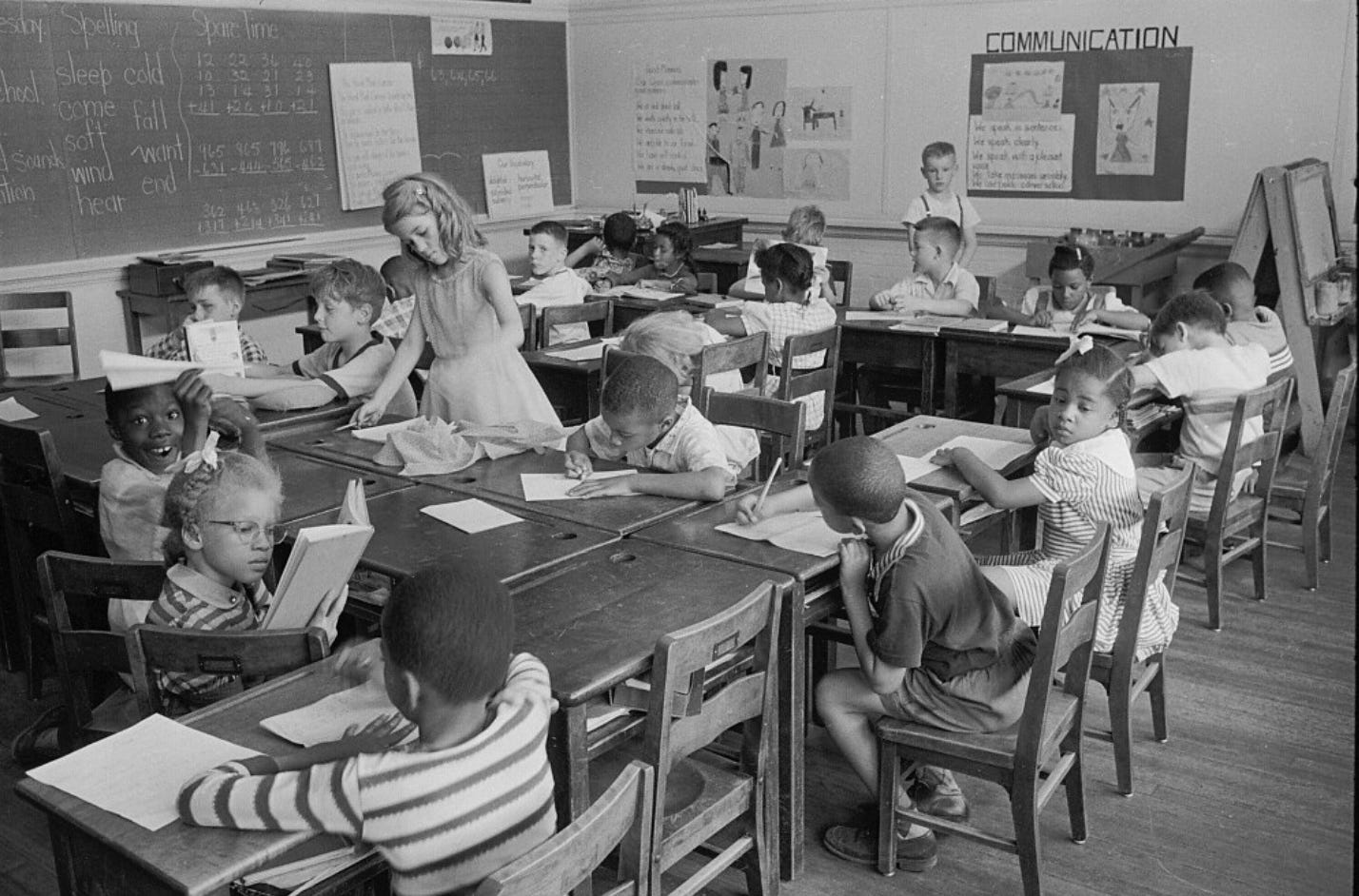

Milwaukee was an early adopter of vouchers, but not solely because of the influence of the Chicago boys and their acolytes. Some of the loudest voices for choice here were Black activists and politicians— many of them strident leftists. Their argument for school choice in Milwaukee was two-fold. The first was that White students, especially White middle and upper middle class students, already had school choice. That’s why they decamped for suburban citadels or gleaming private schools. The second was that a more decentralized system would hopefully enable more pathways for Black and Brown educators to chart their own course, freed from the rigidity and institutional racism of the district. There could be, for example, new networks of Afrocentric schools— educational oases built by and for the Black community. Saul Alinsky used to talk about how in organizing there are no permanent allies and no permanent enemies. There was a lot of that at play here.

Milwaukee’s choice program started small but has grown steadily over the decades. It still has its proponents and opponents, each armed with studies showing that it’s either an abject failure or a rousing success. There are people in this town— Black, Brown and White— who will tell you that the greatest enemy is still the district and the teachers’ union. There are others— Black, Brown and White as well— who will tell you it’s voucher and charter schools and the education reform loving business community. Every side has plenty of data to back up their argument. The fight has gone on forever; I can’t imagine it ever ending. In the meantime , the broader story of education in Metro Milwaukee hasn’t changed dramatically over my lifetime, just as it hasn’t truly changed dramatically anywhere in the country. School systems, like all American systems, continue to serve wealthier, Whiter families better than Black and Brown families, especially poor Black and Brown families.

All of this brings you to this open house, you and your White son and White wife, standing at the front door of an unfamiliar school with a tornado of contradictory thoughts running through your head.

You know full well that the stakes of your choice are so much lower than they are for so many other families.

You know that whatever choice you make, the game is already rigged in your kids’ favor.

You openly resent the fact that you get a choice.

You realize the privilege of that resentment. You feel embarrassed by that realization. What a gift to have your main relationship to this process be mere annoyance.

You try to square an invisible circle in your head, wanting neither to be an entitled White parent pushing to the front of every line, nor a self-righteous White scold trying to pretend that you alone can make the sole virtuous choices in an unvirtuous system.

You try your damndest not to put all of this on your son, whose eyes are wide-eyed, trying to take it all in, trying to see if his friends are here.

You say hello to the perky teenage student greeters. You sound like a chummy, try-hard dad. If the shoe fits, etc. etc. You scan a QR code and take a program.

You’re exhausted, and you’re barely one step in the door. It feels like too much. It’s not the school’s fault. They’re doing their job. It’s everything unspoken: impossibly rusted systems collapsing under the weight of so many seemingly benign individual choices.

You file into the auditorium. Many of your son’s friends are here, too. It feels so good to see them. Later that night, your wife will say “I wish they could just stay at our elementary school forever.” The following day, your son will compare notes with his friends and they will pretend to have specific thoughts about the school, but their primary concern will be that their collective center holds. They want to be safe and secure and to stay with each other. It’s a beautiful desire. You want to support it.

But tonight, your job is to learn about this school. For two hours, you travel from classroom to classroom. There are mini presentations— about STEM, about end-of-year trips, about extracurriculars. At one point, somebody’s third grade sister raises her hand and asks the teacher presenting about electives and why there’s a class called “chore.” The teacher politely informs her that it's pronounced “choir” and everybody lets out a cathartic laugh. It’s an anomalous moment, one where neither the school nor the families have to perform for one another.

Mostly, though, the school is selling. It’s pulling out all the stops. You can tell that it’s genuine, though. The teachers and students are proud of the community they’ve built here: in a unionized district school, with a mostly low-income Black and Brown student population. They’re proud that this is a place where robotics awards are won and AP tests are passed in middle school and artists and dancers and creative writers roam the halls. They’re proud of how well they know and love their students.

You like the school just fine. The teachers are passionate and the students are charming. You’re reassured slightly by the fact that the admissions process here is less cut-throat and zero-sum than it is in so many other cities. It’s not just test scores, you’re told. Its magnet-ness isn’t just a front to pull in all of the city’s White families into one building, or at least that’s what you hear. You especially love that you and your son could bike here, that it isn’t on the opposite end of town, that it’s between your house and your wife’s work. You remind yourself that this is your son and his friends’ choice more than it is yours.

Your son and his friends really like the school. The thing is, they really like the language school too, which isn’t selective and doesn’t win robotics trophies but also has caring teachers. It, too, is totally fine. Are you overthinking the distance? Is that worth tipping the scales of your decision? Is this truly his decision or yours?

You really wish this school (the one whose open house you’re attending) didn’t have an admissions process, even one that promises to look at students holistically. You wish there was no gate. If you wanted, you could critique other things here— the overt language about giftedness and talent, the lack of a Spanish class in sixth grade, the impossibly steep stairs up to the middle school hallway on the fourth floor. But that’s missing the point.

The problem isn’t the school, really. It isn’t that the school has a robotics lab and 3-D printers. It isn’t that its students take trips to Toronto and New York, or that teachers from across the district are all eager to work here. It isn’t the massive light-filled windows in the library or the multiple sustainability awards or the “you’re welcome here” signs underneath Black Lives Matter and trans flag stickers.

The school isn’t perfect, but it has some truly lovely aspects to it. But that, of course, is the real problem. You don’t see anything in this school that shouldn’t be present in every school in the district. The fancy stuff, of course: the equipment and the programming and the trips, but not just that. The fact that the students here feel safe and welcome and seen.

This is not the only school in the district where students feel at home. There are schools spread out around the city where that’s true, many of which aren’t destinations for the kind of parents— Black and Brown and White alike— who seek out open house nights. But it’s also true that not every school in the district could put on this particular type of show. And even more so, it's true that everything that’s a point of pride here would be considered the bare minimum in all the suburban districts to our North, South and West.

You have a choice, it seems. But also you don’t. Because the system that everybody deserves isn’t on the table, and it never has been.

It says something about us as a nation that something this profoundly weird is accepted as normal. Consider, for a second, how odd it would be if residents of a community had to shop for the best fire department, or if fire departments in the Whitest and wealthiest parts of a metro area all had sufficient quantities of special water that actually extinguished blazes, but the central city had to choose which two of its dozens of locations got the good water. And then if we judged each other’s parenting acumen on our ability to “find the best fire house for your family,” or if real estate agents talked brazenly with White parents about how they should avoid “that neighborhood” because it has “a bad fire department.”

Wouldn’t that be odd? And not just odd, but depressing? Soul-deadening?

Wouldn’t it reveal our deep, deep brokenness if each of us were reduced to consumers clawing and competing for what should be a basic public good?

How exhausting. How terrible. How monstrous.

It has been a few weeks since the open house. You still don’t know what you’re going to do about school next year. Your son and his friends are applying to the place with the robotics lab and the trips, but you remind him that doesn’t mean the decision has been made. You’re talking about it together. It’s a teachable moment, you tell yourself.

There’s an argument to be made that you’re being too self-aggrandizing about the whole affair. Your individual choice will mean very little in the grand scheme of things. Your per-pupil family dollars will go to the same underfunded public school district one way or another. How your White family shows up in the mostly Black and Brown schools you are choosing between will make more of a difference than the specific school where you land. And you do believe all that, to a point. And yet… there was a reason why you biked rather than drove to the school that open house night. Just because the world is full of terrible choices doesn’t mean that nothing you do matters.

Your son worked on his application this past weekend. He recorded a video where he outlines his vision for an ideal light rail system for Milwaukee. It’s a lovely scene—in essence, your now-not-so-small child articulated his dream for how to stitch together a disconnected, segregated city. You watched it a few times, smiling like a goof dad. You couldn’t help but flash back. Suddenly your son was four again, staring up at his new principal in a school without any admissions process, the same one that regularly receives a profoundly mediocre score on state report cards. You remember her question, “what’s your name and what do you love?” You remember him giving his most possible honest answer back. “I love trains.” In essence, it’s the same answer he’s giving right now.

You remember your son near tears. You remember yourself near tears. But you also remember the principal’s response. “We’ll make sure you can learn about trains here.”

That’s all you want. Not that conversation precisely, but something like it. And not just for your kid. For every kid.

End Notes:

If you, like me, are a U.S. resident who believes that every human life is precious, please keep calling for Congress and the President to immediately call for a cease fire in Gaza.

I took a few weeks off of Song of the Week, but it’s back! I’m surprised I’ve never picked Mission of Burma’s “Academy Fight Song’ up to this point, because “I’M NOT JUDGING YOU/I’M JUDGING ME!” is an extremely White Pages sentiment. I’ve also been singing the chorus as “I’m not not not not not not not not not… your middle school open house,” which doesn’t really work but here we are. Oh, and as always, he Song of the Week playlist, is on both Apple Music and Spotify.

Just a couple plugs before we go:

You all, I’m currently spending just about every waking, non-parenting moment immersed in copy edits for The Right Kind of White and I have to say, all doubt and self-deprecation aside, I really believe in this book and can’t wait for you to read it. Thanks so much for all the pre-orders (and remember, after you pre-order definitely fill out the thank you form so I can get you a gift).

If you’ve been on the fence about becoming a paid subscriber to this space, I have to say… our recent community discussions have been some of the most beautiful and fascinating experience I’ve had on the Internet in recent memory (and remember, if you can’t afford a subscription, just email me- I have a no questions asked policy on comps)

With love: STOP MICRO TARGETING ME

It is so hard. We want to make the right decision for our kids and for our neighborhood and for our city and it's not even that the right choices are in conflict with one another, it's that there really doesn't feel like there are any right choices available. Of course our family choices aren't going to fix this. And you rightly note that schools are at the end of many funnels. And still!

When we moved to Milwaukee a realtor confidently told us not to worry: that we still had time to move to Tosa before our kids were school-aged. She couldn't fathom that we wanted to be here, yes, for the schools. That "the right choice for our kids" for us meant we didn't want our kids to grow up in a racially and socioeconomically homogenous environment. And still.

I worry about what we lose as a community, as neighbors, without the anchor of shared, neighborhood schools. And I understand why so many black and brown activists fought for a chance to not just directly inherit the inequalities baked into residential segregation. And I, too, am annoyed that this choice is on me at all, and embarrassed at how low stakes, ultimately, it is for my family. And still.

Vouchers and giving parents "choice" is hot topic around my area. Our governor promotes it fiercely, the same guy who won't do anything to improve gun violence in schools. My retort to his sound bites is "what choice are you giving me, choice of morgue??". It infuriates me.

I loved your comparison to fire departments and the quality of water to extinguish flames. I was reminded of "food deserts" that leave poor communities, often non-white, without access to fresh foods and healthy choices. Access to good food and education should be like a utility, and not a "choice" for those privileged to have the means to make one.