The day that the Fonz solved racism

Kicking off the White Pages summer movie series with an artifact that is very much not a movie (but that I can't get out of my head)

There’s a popular truism about the evergreen popularity of 30 minute sitcoms. It’s the kind of statement that can be repeated without rigorous fact checking, because it feels accurate: life is hard, but situation comedies aren’t. You’ve no doubt heard this before; it’s the “all the problems are wrapped up in thirty minutes” of it all.

I don’t have a counterpoint, by the way. Every sitcom I’ve ever loved is essentially about a group of friends or colleagues who, even if their lives are different than mine, feel close enough to real people that I don’t have to squint too hard. But unlike real people, all of the things that feel most tragic and intractable in our world— loneliness, isolation, poverty, abuse— are either absent altogether or solved with some tidy hand-waving. Nobody is left out in the cold, at least by the time the series finale rolls around.

You know who’s a particularly brilliant character, if you’re a believer in the whole “we love sitcoms because they’re a cleaner version of our messy lives” concept?” The Fonz. That’s right, Arthur Herbert Fonzarelli from Happy Days. I grew up long after that show’s heyday. For my generation, Happy Days was the show from that one Weezer video. Have I even watched an episode of Happy Days in its entirety? Maybe not. But you don’t have to watch Happy Days to understand The Fonz. He’s cool, you see, but not mean. That’s his whole perfect deal. He wears a leather jacket and rides a motorcycle and is an incredibly sought-after romantic partner. But in spite of all that, he still hangs out with the show’s main characters even though they’re a bunch of squares. Isn’t that what we all want? For the coolest person we’ve ever met to have our back. For all the busted jukeboxes in our lives, both real and metaphorically, to be fixed with a quick, benevolent punch.

Happy Days aired in the 1970s but is set in an idealized version of 1950s Milwaukee. Its entire reason for being is to tell a complimentary, sepia-toned story of a then-recent past. What were the ‘50s like? A blast! Nothing but malt shops and goin’ steady and be-sweatered White people cracking wise. Happy Days wasn’t about facing hard truths or wrestling with America’s various sins. It was about rocking, and doing it around the clock.

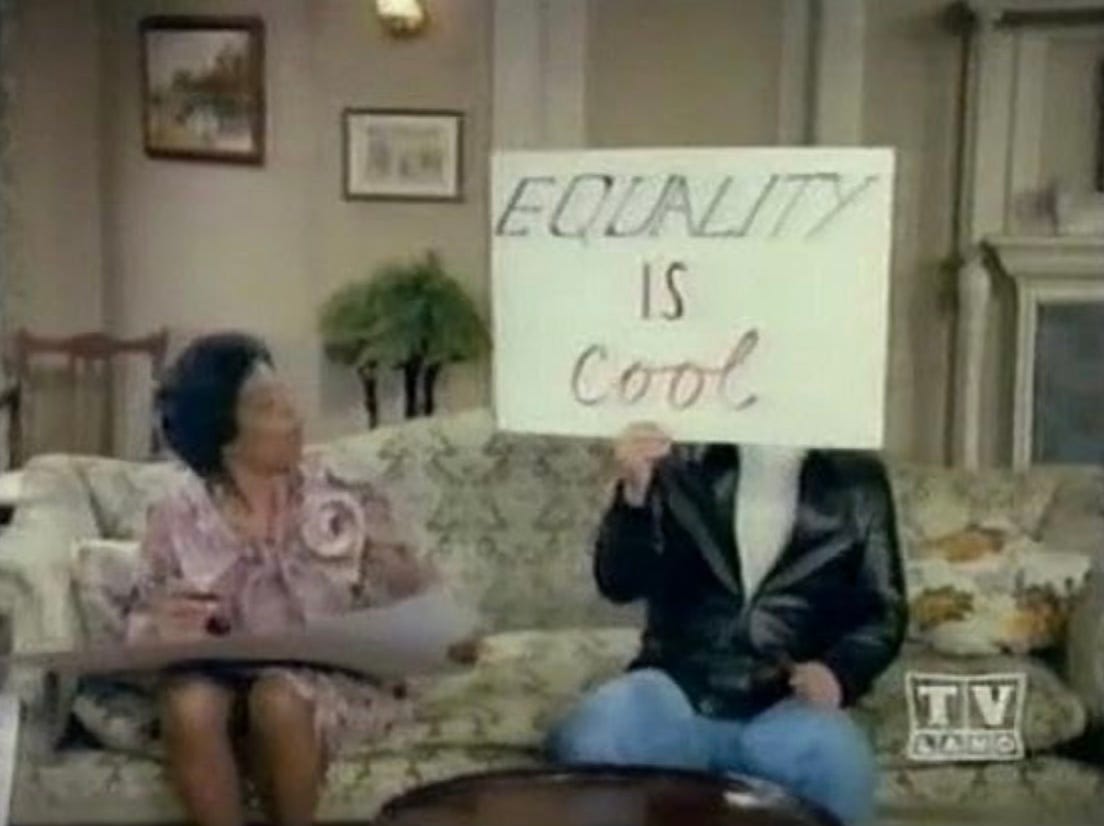

It’s notable, then, that in its ninth season (notably, four seasons after the whole business with the shark), Happy Days attempted to tackle the topic of anti-Black racism. A bold swing. That episode, “Southern Crossing” isn’t available online, but you can watch its climatic scene on YouTube. Its premise is as simple as it is credulity straining. Angered by scenes of Bull Connor-style police violence on TV, Fonzie and Al (the lovable owner of Arnold’s drive-in) Freedom Ride themselves down to an unspecified Southern state to join a Civil Rights march. They stay with a kind Black couple, Henry and Annie Douglas, but initially fail to impress their young adult son Charles (a sanded-down, primetime-friendly simulacra of a cynical Black Power activist). All this leads up to a dramatic show-down at a Jim Crow diner, where the power of White supremacy is no match for the force of Arthur Fonzarelli’s effortless charisma and devotion to liberal pluralism.

The diner scene is worth watching in full, but if you’re wondering if it hits a metric ton of pleasure-center-gratifying story beats, don’t you worry. Are the southern racists put in their place with remarkable ease? Yes. Does previously skeptical Charles come around and accept Al and the Fonz as trusted friends and fellow travelers? Also yes. Most importantly of all, does the scene conclude with Fonzie hitting a “Whites Only” sign as if it’s a malfunctioning jukebox? Ayyyyeeee.

Notably, the hero of the diner scene isn’t any member of the anti-racist trio, but Mae, a waitress who has long hated her boss’ racism but consigned herself to silence. Suddenly inspired by the two prophets from the North, Mae finally puts her foot down. She serves the multi-racial trio their cups of coffee, daring her boss to fire her. When the diner’s owner balks, deferring to his best employee, the generational spell is lifted. The sheriff stands down, the good ole boys disappear, the owner slinks to the corner to reconsider his life choices. Segregation is over, if Mae wants it.

It’s easy to fire off take-downs of “Southern Crossing’s” flimsy racial politics. Yes, it’s a one-dimensional White savior story, one that imagines 1950s Milwaukee as a racial utopia whose White people were all pure of heart (fact check: untrue!). Yes, it traffics in tired myths of uniquely racist White southerners who just need a good talking to. But those tropes exist in every genre— from academic texts and activist pamphlets to full-length motion pictures. There’s something uniquely revealing, though, about the way they pop up in a pointedly apolitical sitcom from a half-century ago.

If I’m being honest, it’s the applause breaks that won me over. I haven’t mentioned those yet, but this is an episode that takes full advantage of the “filmed in front of a live studio audience” conceit. Again, if you have a few minutes, watch the scene. It’s a blast. Every action inspires a perfect studio audience reaction. Fonzie mocks the racist good ole boys’ accents. The audience laughs. The waitress takes a stand. They cheer. The Fonz hits the “Whites Only” sign off the wall. The unseen masses absolutely lose it. And listen, so did I. I felt all that. It was so satisfying.

We are savvier than this. We know it’s not that simple. We are well aware that an anomalous act of bravery won’t bring about the better world of our dreams. But sitcoms are wish fulfillment vehicles, which is another way of saying that they are revealing of everything we secretly want to be true about our lives but are too wise to speak out loud. Yes, I’m talking about Whiteness’ unquenchable thirst for saviorism. But it’s not just that. We are all human beings who are frequently exhausted by the state of the world. Of course we wish that the revolution required nothing more than a satisfying but finite afternoon’s worth of work.

I spoke in Minneapolis this past week. I’ll write more about that experience in a future essay, but suffice to say it was a profound gift. You see, my workshop was on Thursday the 23rd. Two days later was the 25th of May, the anniversary of George Floyd’s murder. The crowd included at least a few of the activists who’ve been keeping the flame of community and justice alive in that city long after the news cameras packed up and went home. There have been victories in the past four years, but there have also been defeats. Even more so, there has been the familiar slog of work that is part and parcel of efforts to steer the ship of our shared lives in a loving direction. Meeting agendas to be sent out. Childcare to be coordinated. Egos to be managed.

Every year, as the anniversary grows nearer, national outlets cue up retrospective pieces. Reporters call Minneapolis activists up and ask “why has so little changed?” It’s a revealing question, not about that community’s unique failure to completely liberate itself, mind you, but about our collective unrealistic expectations for what it means to “do the work.” We don’t often admit it, but back in 2020, many of us truly did hope that, if only we were righteous enough, if only we yelled louder at the march or made a more impassioned social media post, perhaps all of America’s “Whites Only” signs would come crashing down from metaphorical diner walls.

I don’t blame this impulse, mind you. I just wish we acknowledged it. When we show up, even in small ways, for a social change effort, there is often a battle raging between our head and hearts. Our heads know that life is not a sitcom, but our hearts wish that wasn’t the case. Because the truth of the matter is, we may work our entire lives and, on the day we depart from this world, justice will still feel miles away. There will be no final roar from the audience, no satisfying resolution before the end credits. And in our wiser, calmer moments we recognize that. The most even-keeled among us may even be able to hold to their place in a longer generational lineage. It’s not about whether we personally get to the mountaintop. It’s about gratitude both for the footprints behind us and those that will one day extend far past our resting point.

But our hearts betray us, those tender vessels of vulnerability and longing. Of course we show up once— for a protest, a workshop, a social media call to action— and wish that was all it took. Of course we wish that we could go to bed in brokenness and wake up the next morning to discover that every human being has a home and nobody fears for their safety and the bombs aren’t dropping on children in tents. And thank God for all that. Because embedded in those wishes is evidence of how much we love each other, how much our hearts really do break for one another’s suffering.

It’s a silly piece of art, “Southern Crossing.” Did I mention that, right after Mae takes her stand, she and the Fonz kiss? Of course, they did. Have you seen The Fonz? He wears a leather jacket! It’s all so dumb, in the absolute best way. But friends, when I turned off my protective armor of pop critical theory, it really did work on me. Which means, naturally, that I too wish that this work was easier and more consistently gratifying.

I’ll keep pushing myself to show up to more long, interminable meetings. But what’s more, I’ll be a little more grateful for the mere existence of those gatherings. The tender hearts gathered around me? I bet they too wish that life was more like a sitcoms. They too had to push themselves to get out of the house that evening. They too haven’t done enough, for long enough, but at least we have one another. At least we’re still here, at least we’re still trying, both because of and in spite of our silly little hearts.

Another absolute bounty of end notes:

And with that, I’ve soft-launched the White Pages Summer Movie Series. For those of you who weren’t here last week, here’s how it works.

Most weeks in the summer, either myself or a guest author will write about a movie that says something interesting about Whiteness and the stories it tells itself.

I reserve the right to pause the series at any point if I get bored or if I’d rather write about something else.

I call it a “summer movie series” but maybe we’ll still be doing it in the fall. Who knows!

The list of movies is subject to change, but this is what it looks like currently.

If you have a pitch for one of these movies, send me an email— garrett@barnraisersproject.org. I pay all contributors more than many of the big fancy outlets (thanks paid subscribers!).

Speaking of paid subscribers, some of these will be free, others paywalled.

If you want to get in on all the fun sooner rather than later, here’s a button that, for the next week, will give you a discount on a subscription. Not bad!

The book is still out in the world and it’s so lovely to hear from you all as you read it. Thank you. Do you not have a copy yet? I’d love if you would check it out. And if you buy one and want a comped subscription to The White Pages as a thank you, just email me. It’s the least I can do.

The spring leg of the book tour is winding down. I’ve loved it, but also I’m writing this from an uncomfortable bench in the LaGuardia Airport baggage claim (New Yorkers, it’s my first time flying here since the remodel— on one hand it’s very nice but there is nowhere to sit!), so it might also be time for a break. But first, more fun…

Next Tuesday, June 4th, I’m in the Literal Redwoods (well, not the city of Redwoods, I mean the town with the redwood trees)! Mill Valley, CA at the Mill Valley Public Library! 6:30 PM! Shout out to Sausalito Books by the Bay and Madrona Bakery for being co-sponsors here! Please RSVP. It helps the library know how many chairs they’ll need.

On Wednesday, June 5th, 7:00 PM, I’m in Oakland, CA and we’re gonna do a “Garrett Bucks and Friends” workshop/hang-out/book talk/good vibes time. Where? Temescal Commons, 480 42nd Street. You all, it’s gonna be so rad. RSVP for that one here.

Residents of Washington State! Or people who care about residents of Washington State! Did you know that there is a grassroots campaign to get y’all actual universal healthcare? It’s true. It’s called WHOLE WASHINGTON and I’m leading a public, virtual organizing training for them on June 19TH at 6:00 PM PT. RSVP here.

After all that, I’m taking July and August off from book tour but will be back at it in September. If your ragtag community group would love a guest speaker, well, let’s just say I know a guy. Let’s talk! garrett@barnraisersproject.org.

It feels pretty obvious to pick a Buddy Holly number for the song of the week (what with that Weezer song with the Fonz in the video being called “Buddy Holly”), but also “Everyday” is one of my favorite sweet songs about our simple dumb hearts. Let’s not overthink it. A hey, a hey, a hey, a hey.

I am of an age that I *did* watch Happy Days as it was airing. The Fonz wasn't my first tv crush (that would be Speed Racer), but he was fairly high up the list. My greater affection was for Pinky Tuscadero, though. Cool redhead role models in pop culture were few and far between in those days and Pinky was THE BEST.

Your essay is allowing me to put words to something, though, and I'm really appreciating that. Namely, that there is a need (based on an obvious lack) of people in activist spaces whose primary job is to model and push for emotional intelligence. We have to change systems. That's the big goal, yes? But systems are full of people who are affected in a variety of ways connected to identity, trauma, and trauma's close cousins-- rage, disassociation, spiritual bypassing, conflict avoidance, etc. Doing big system change work, in other words, gets us way up in our feelings, but somehow taking the time to acknowledge that and figure out how to support each other through that is often considered indulgent, beside the point, or a deliberate attempt to derail "the work" to coddle the White folks in the room. And it can be indulgent. And it can be derailing. But it doesn't have to be. And I suspect that if we don't figure out how to do that deep emotional work together the big system change work will always eventually be undone because *we* aren't changed in the end.

I'm beginning to suspect that's the thing I actually bring to the work, that commitment to supporting the development of emotional intelligence in our change-making spaces so that the system change we make changes us.

Henry Winkler is a National treasure . I arranged his appearance at a Gala of 500 for The Springer School in Cincinnati. Children with learning issues who go on to become excellent highschool , university and varied professions. He has written Hank Zipzer. Children’s books about different learning issues. Anyway he sat with my husband and me. Spoke to guests 30 plus minutes. Sans notes. He’s dyslexic (you probably know and a Yale grad ) his last words “ Thankyou for listening my parents never did.”