The hundred year old movie that predicted our current reactionary moment

This week, The White Pages summer movie series dares to ask "if it's a silent movie, why is it yelling at me?"

Some weeks, I publish this newsletter and immediately get a flood of responses about how readers were hoping that I’d choose that particular topic. This usually happens when there’s a singular news event that many of us are processing in real time. I try, as a rule, not to chase zeitgeisty topics just for the sake of it, but I do appreciate the moments when the thing that’s on my mind overlaps with the topic many of you were craving an essay about. What a gift, to feel less alone in our thoughts, together.

Those weeks, this whole enterprise makes a lot of sense.

Other weeks, I write an essay about a long-forgotten 1916 silent film from a famously bigoted director, a three-hourlong epic with four interconnecting storylines and a lot to say about the Huguenots in sixteenth Century France.

What I’m saying is that I’m not expecting any “thank you soooo much Garrett, for finally writing about D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance this week.” And listen, I get it. I’m not encouraging you to actually watch Intolerance. I mean, it’s got some incredibly impressive set design, and it’s literally available for free on Youtube, but come on. It’s a three hour long silent movie from 1916. Do you think I was on the edge of my seat? I had to break it up in spurts and ban myself from looking at my phone. But stick with me.

What you need to know about Intolerance is that it was the movie that D.W. Griffith made immediately after Birth of A Nation. That film, of course, is one of the most discussed works in American cinematic history, both for its contributions to the craft of filmmaking and, of course, because it’s really, really, really racist. We’re talking “so racist that the NAACP launched a decades-long campaign against it” racist. We’re talking “it spurred a major resurgence of the KKK because its core message was, ‘hey White people, we should do the KKK again” racist. We’re talking “Woodrow Wilson’s love for it will always be one of the three arguments given to show that Woodrow Wilson was an unrepentant bigot” racist.

So let’s say you’re D.W. Griffith. Birth of a Nation was a huge financial success. You’ve been lauded as the best director alive. But Black people and White Northern liberals are extremely mad at you. They’re calling you racist just because you made a super racist movie. What’s your next move? And, more importantly, why did that next move matter, a hundred years later?

On any given week, you can find me, by choice, reading or listening to somebody to the right of me who are bummed out that their viewpoints are not universally beloved. I’ve listened to multiple episodes of the Joe Rogan podcast about how you can’t tell any good jokes anymore because people are just too damn sensitive. I’ve read anywhere between one and one hundred New York Times op-eds about how the trans people need to just tone it down, specifically for the benefit of the sensibilities of New York Times op-ed writers. For a month there (while I was preparing my piece on Nellie Bowles’ Morning After The Revolution), I was even a paid subscriber to The Free Press, a publication that covers DEI trainings at elite private schools like ESPN covers NBA free agency. Do you ever wonder if anybody read both Ron DeSantis AND Vivek Ramawamy’s most recent books? I did. Please clap.

As I hope was clear in my Bowles' piece, I think there’s a point to all this listening and reading. It’s not just a stunt, nor even a classic “know your enemy” deal. I pay attention to popular reactionary thinkers (a term I use for anybody, from across the political spectrum, whose essential argument is that we need to do less rather than more to correct for existing societal hierarchies), because, well, I do dream of a better, more universally loving world. I would like fewer people to be left behind by economic and racial and gender-based caste systems. And if that’s the case, I find it helpful to understand the arguments people make when they resist that change, not just to counter them but to parse out what makes them appealing.

You know how, just a couple paragraphs above, I essentially charged that these thinkers are obsessed less with the fact that they’re not allowed to believe and say whatever they want but that they escape criticism for it. That’s not a trenchant point. I don’t intend it as a cheap gotcha, though. I have the same overly-self-conscious, desperate-to-be-loved and accepted brain as all those reactionary writers and podcasters. The vast majority of us do. I mean, I think that’s core to the appeal of reactionary thought-leaders. None of us are actually fully confident in how we’re walking in the world, and it’s comforting to have somebody reassure you that you’re ok, that it’s the haters that are wrong.

All that’s well and good, but let’s go back to 1916. How did D.W. Griffith respond to criticism of Birth of a Nation? By bankrupting himself making one of the most expensive, ambitious movies ever in order to prove that he wasn’t the bigot, it was his critics who were the bigots.

I’m going to do my best to summarize Intolerance’s plot quickly, but it’s a bit of a Gordion knot, so bear with me. There are four stories, all Tales of Intolerance Throughout History (sort of). The film cuts between them at a rapid clip (think Pulp Fiction or Nashville or Love Actually if any of those movies were directed by a man desperate to show how Not Mad he was). We spend a bit of time with Jesus (famously killed due to the Pharisees’ lack of tolerance for Jesus, specifically) and also pop over to Imperial France as the seeds are planted for the St. Bartholomew’s massacre (more death by intolerance, this time towards those poor Huguenots).

Those two storylines are relatively brief, though. Most of the movie’s runtime is spent in Babylon (Griffith is a big fan of Babylon! He thinks they had some really good ideas, and specifically argues that Babylonian women really liked being sold at marriage markets!) and what Griffith calls “The Present Day” And if we’re being honest, the Babylon subplot (though visually impressive: There! Are! Elephants!) is mostly just a more convoluted rehashing of the “religious intolerance is bad” message from the French section. So it’s clear that Griffith’s main interest lies with his contemporary melodrama, which follows the plight of poor mill workers turned urban migrants. All of the other plot lines exist to reinforce that story arc’s clear, heavy-nanded moral.

Why is the Present Day subplot so important to Griffith? Because it’s an opportunity for him to really stick it to his haters, of course. And what a gift for us that he felt that need, because even though Intolerance is one hundred years old, every single one of Griffith’s rhetorical moves will feel familiar to contemporary audiences, because they’ve now become tried and true weapons in the reactionary arsenal.

Here’s a small sampling of Griffith’s arguments. You’ve heard these before, haven’t you?

We’re all against intolerance and hatred, right? Well, what if I told you that intolerance isn’t a new thing, nor an American project, but that it’s always been around. There was intolerance in Babylon, for God’s sake! [See also: Every single contemporary critique of “woke history” or “Critical Race Theory” that argues that slavery has existed in every society in the world but the U.S. was the first place to ban it, which means that the founding fathers were the original anti-racists].

You know who are a bunch of hypocrites? Elite White liberal women employed at nonprofits. You know, like the ones who might have criticized Birth of A Nation [Ok, so this is fascinating. The arc of the “Present Day” subplot is that these scoldy White Reformer ladies get a huge grant from a robber baron for their do-gooder foundation, but to pay for that grant the robber baron has to suppress mill worker wages. The workers respond with a strike, which is then broken up violently, leading to a long convoluted domino effect of tragedies that push the next generation into urban slums, whose conditions are subsequently made worse by the meddling of the annoying nonprofit ladies— more on that in a bit].

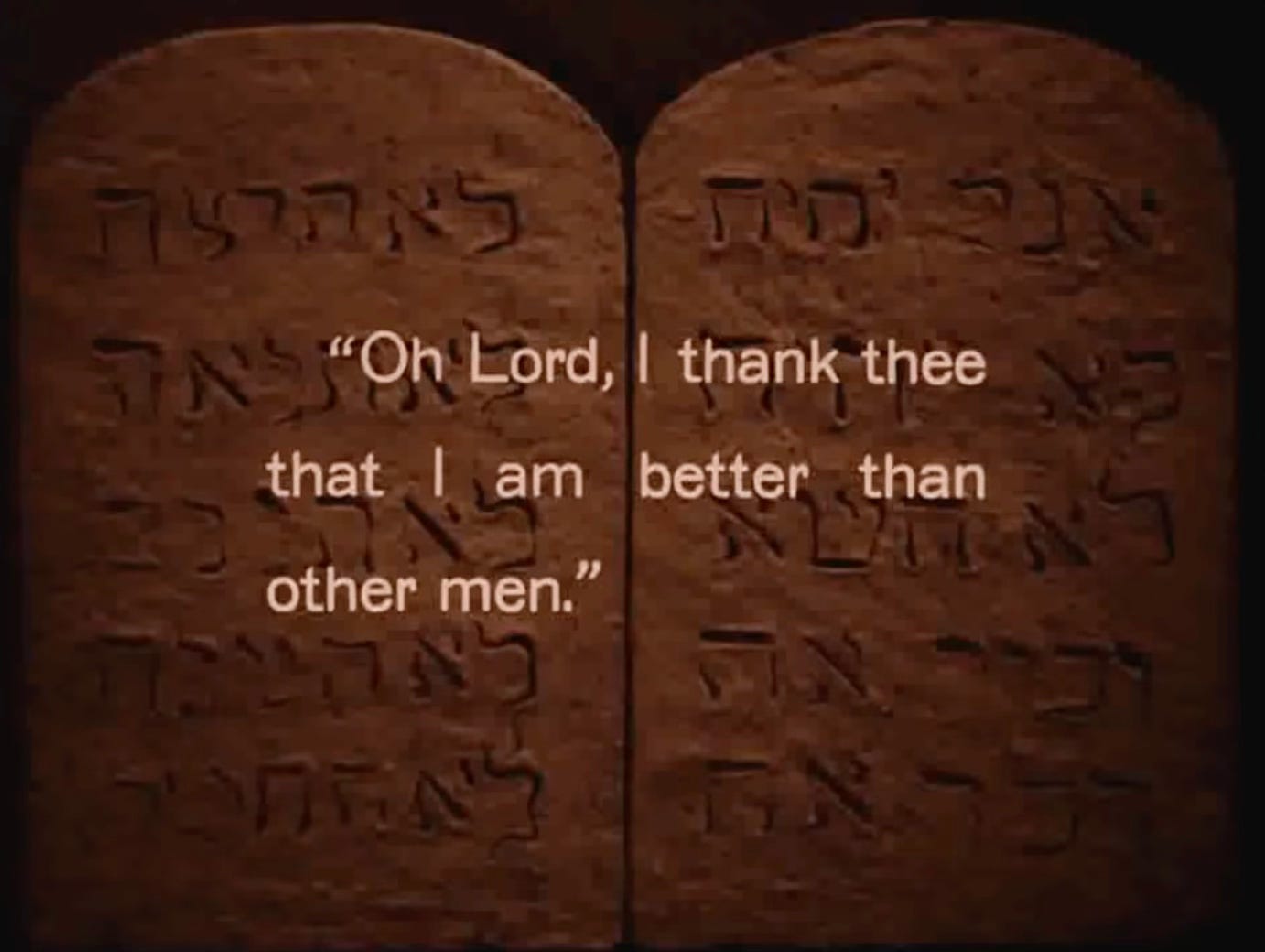

Oh, remember how the Pharisees enabled Jesus’s death because they were a bunch of haughty hypocrites who thought they were better than everybody? Well, the Nonprofity White Ladies are just like them! And also, nobody loves them because they’re ugly! [Both these points are made explicitly].

So yes, I did have to watch this very long movie in spurts. But also, as it kept going, and as more death and despair was delivered to the one-time mill workers at the hands of the Evil Nonprofit Ladies, my jaw kept dropping.

I mean, you all, we lived this movie for the last four years. Every single “DEI/Critical Race Theory” debate has essentially been an Intolerance redux. It’s all there: the “I’m not the racist, you’re the racist for talking about racism” discourse, the easy slide into misogyny(see also: how quickly “Karen” was fully adopted by the right as a slur for any left-leaning woman they don’t like) and most of all, the way that good faith, necessary critiques of corporatized equity work end up getting lost in a see of bad faith arguments about how Bud Light has gone woke now (the irony, of course, is that the real story of union busting and the birth of philanthropy is even more nefarious than Griffith’s imagining, but the villain of that story is capitalism itself, not a few scold-y liberal ladies). There’s a lot of this in the Present Day subplot, moments when Griffith could offer trenchant social commentary (about mass incarceration or the child welfare system or any number of structural injustices) but instead merely wants to needle the eminently needlable Annoying Reformer Women.

There’s a mystery at the core of well-platformed reactionary thought. In a word: why? You all have already won. Griffith made a blockbuster film celebrating White Supremacy (one of the core building blocks of American life) and was rewarded for doing so with riches and adulation. Contemporary reactionary thinkers pine for the opportunity to attack trans people and diversity programs in our nation’s papers of records and then… are literally given those opportunities. A vainglorious New York real estate developer wishes to fill the hole in his heart by amassing power and adoring crowds and gets to be America’s big loud arena rock President. In every case, they’re not being silenced by elites. They are the elites. But they can’t stop complaining about how somewhere out there (again, most likely an Oberlin dorm room), some people believe that their worldview is retrograde and unhelpful. And they still keep whining about their haters. Why?

The easy answer is to just chalk it up to a moral failing on their part. That feels extremely satisfying, for sure. But I think there’s another lesson there as well. When a human being can’t shut up about how others are criticizing them, it does, in fact, show an unease about their beliefs and worldview. When we don’t experience cognitive dissonance, criticism doesn’t impact us. Whenever I receive a threatening message about how my writing makes me the real racist, it doesn’t really bother me, because the argument they’re countering isn’t a belief with which I’m struggling. On the other hand, back when I worked in education reform and I’d hear a critique from a friend affiliated with teacher’s unions, it stuck with me. Outwardly, I’d react defensively, but internally I’d obsess over it. What if they were right? What if the charter schools with which I worked were making it harder to run school districts that served all kids? If you encounter somebody who can’t stop talking about their haters, it’s often because of a doubt with which they’re not yet ready to admit to publicly.

I offer that reading not because I think we should spend much time trying to change the minds of people who make six and seven figure incomes off of spouting their particular opinions. I mean, I’d love for that to be the case (for those wondering, I’m sure Nellie Bowles never saw my piece with questions for her, but if it ever does make its way to her I am still curious!). But I think it is useful for the millions of people in our own lives who are trying to make sense of this moment. Are we giving them space for their struggles, even when they might not be articulated with a perfect vocabulary yet? Do we want the only outstretched hand to come from the professional reactionaries? And most of all, who are we to each other, those of us who dream of a more just world, not just in our moments of certainty, but our moments of doubt?

End notes:

I’ll be on vacation for a couple weeks, but we’ve got two great guest movie series essays on tap for you (another reason to become a paid subscriber, so that I can pay contributors at a rate higher than the big fancy publications). These are going to be so good, you all.

The Right Kind of White spring/summer tour is over, but I’m working as we speak on some fun fall dates. If your organization is looking for a fun night with an, um, very energetic speaker, holler at me. Let’s talk. garrett@barnraisersproject.org.

Speaking of me talking about the book (which, by the way, you can and should still buy), want to see me on CSPAN Book TV? Oh jeez, do I really move my arms that much when I talk? (Everybody who has ever known me nods ‘yes’). I’m working on it, friends.

Father’s Day was Sunday. You know what’s the best retroactive Father’s Day gift you can give to all the dads in your life? Listening to me on the

podcast talk about Mamma Mia and the search for middle aged male friendship. And then keep listening for the next episode, about Ruth Whippman’s Boy Mom, which rules.Paid subscribers: It’s been a few weeks since we’ve done a Thursday community discussion. Let’s do one this week, eh?

I DJ’d my niece’s Bat Mitzvah this past weekend and… I think people had fun? I had fun. I learned a lot about the Venn diagram of music I like and music that West Philly teenagers like. We do not have the same opinion about Travis Scott’s songs that are mostly just grunting. We’re both neutral on Sabrina Carpenter (you might say that shared opinion is that us, espresso). But Chappell Roan? We all like Chappell Roan. Fun fact, “Good Luck, Babe!” was written about D.W. Griffith! [not true].

thank you soooo much Garrett, for finally writing about D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance this week.

Great! Now do Broken Blossoms, please.