The old commune is a park now, and the schoolhouse where they founded the Republican Party is across the street from a vape shop

Dispatches from Ripon, Wisconsin

Here’s one way of telling the story…

In the mid-1800s, an idealistic group of far-left dreamers founded an intentional community in rural Fond du Lac County, Wisconsin. They named their commune Ceresco, after the Roman Goddess of the harvest. Like dozens of other utopian experiments that sprouted up in that era, Ceresco was an attempt to live out the teachings of the proto-socialist French philosopher Charles Fournier: communal living untethered to the nuclear family, equitable distribution of wealth, libertine sexual experimentation. Typical commune behavior. But while many other Fournier-inspired phalanxes barely lasted a few years, Ceresco was, for nearly a decade, a comparative success. Tight management and shared ideals kept in-fighting and drama to a relative minimum. A hardy Badger work ethic and a string of good luck enabled a decent level of prosperity. At the time it disbanded, the community had a positive balance sheet, a rarity in the world of shared living.

Though Ceresco did not live forever, many of its alumni continued its legacy of social action, moving out of the former community’s longhouse and merging with the neighboring town of Ripon, Wisconsin. Alongside other town radicals, the former Cerescans helped make Ripon a national center for abolitionist politics, most notably founding a political party that, not long after its formation, would successfully abolish slavery and chart a course for reconstruction and reparations.

That’s one way to tell the story. And it’s completely true.

But it’s too tidy. It omits too much. Orwell once argued, discussing Gandhi, that “saints should be judged guilty until they are proved innocent. ”Few of us need that reminder, though. We’re a cynical bunch, us human beings. We assume that other people’s legacies are sullied, likely because we know what kind of imperfect, fumbling, less-than-loving lives we ourselves have lived.

So ok, let’s sully away, if only to massage our own fragile egos.

Why was their nearly free land in that corner of Wisconsin available to a bunch of starry eyed White hippies? Ask the Winnebago and the Potawatomi. And Fournier? The revolutionary thinker du jour for young America’s leftist salon set? His class politics were admirable, and he was a feminist, at least of the self-proclaimed variety. But he was also a vehement anti-Semite. And while many of Fourier’s followers would highlight his admirable beliefs and downplay the loathsome ones, that’s not how legacies work.

As for that commune, whether it was more successful than most, the fact of the matter still stands. It couldn’t sustain itself. And though there are differing theories as to why it collapsed, the most compelling one is that Ceresco’s relative financial success proved to be its own undoing. Like so many social enterprises that offer participants the chance to “do well while doing good,” many Cerescans left because the siren song of “just doing well, without doing good’ was much more seductive. If they could make decent money in a commune, just think of what they could make homesteading on their own, without all the utopian fluff.

So the dreamers? Sell outs, and greedy ones at that. Plunderers of Indigenous land for White gain. And that’s not even to mention their sexism. For all their talk of gender egalitarianism, the meeting remembered fondly by history, the one where they officially founded a new political party, was only open to men. There had been a previous meeting, one where women both attended and spoke passionately. Substantively, the content of both meeting was nearly identical. But only one is canonized as an official origin story.

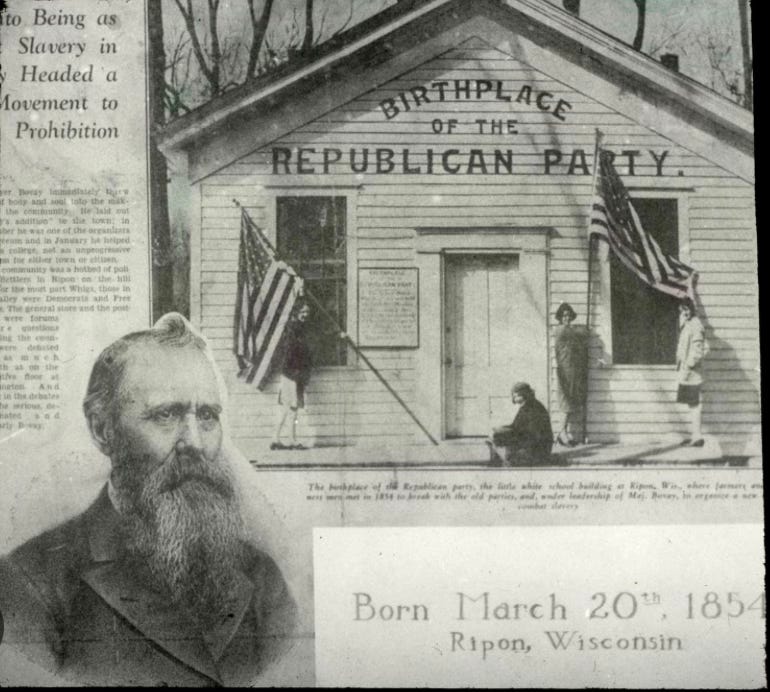

Damning evidence, all of it, but just a preface for the Cerescan’s largest failure. The Republican Party, famously founded in a little white schoolhouse in Ripon, was supposed to disband after America abolished slavery. That’s not how American political parties work, though, not when Republicanism had early allies in the Northeastern business community, not when there was more money to be made and power to be accrued through a long line of strategic evolutions. Reconstruction was scuttled when it threatened those big city business interests. A few decades and a few compromises later, the Gilded Age reigned supreme. Coolidge and Harding played the market and let the market play them. Nixon took the strategy South, and Reagan and MAGA brought it nationwide again. Before long, the Grand Old Party had new slogans. This summer, when they gathered for their convention an hour and a half south of Ripon, the raucous crowd waved placards that read “Mass Deportations Now.”

Every few years, the party would repeat the story of its humble school house founding again. This is who we are. The party of idealism. The party of freedom. The party for all.

Speaking of storytelling, Ripon was in the news last week, on account of Kamala Harris and Lynne Cheney coming to town. They had a rally on the campus of Ripon College. The latter reiterated her endorsement of the former and encouraged other anti-Trump Republicans to follow her lead. There was no discussion about what the G.O.P. once stood for nor what happened in the intervening century. But of course there wasn’t. Their target audience wasn’t people like me— weirdo historical pedants with an interest in long-forgotten socialist communes. The rally was for Republicans. Individuals for whom the folksy iconography of a little white schoolhouse and Lincoln-Douglas debates might tug at heart strings. Individuals for whom Trump is a traitor to the founding vision of the Ripon radicals but the Cheneys somehow aren’t. Individuals who, according to conventional wisdom, will decide the election.

I’m not going to offer any further comments on the Harris-Cheney rally, because once again… it wasn’t for me. I’m neither a Cheney Republican nor a Cheney Democrat. Maybe it worked, maybe it didn’t. We’ll see in November, I suppose. And then perhaps after that, if we’re lucky, when a big tent campaign has to somehow manage everybody it corralled inside.

What I will say is that yesterday I drove to Ripon because I can’t stop thinking about the butterfly effect story of that place. One day a French socialist tells his followers to found a bunch of communes and then a couple hundred years later a once-and-potentially future President is musing about how great it would be if this next time he could really be a dictator. I don’t like that story. I much prefer the one about how a small group of caring committed citizens did in fact change the world. But which one do I get to believe?

Ripon is lovely in the fall. The college is perched on a hill right above a charming little downtown. Apparently many of the townies who initially settled on the hill were distrustful of the Ceresco weirdos in the valley below. Rumors of free love will do that. Today it’s all one town, home to about 8000 primarily White Wisconsinites of varying political stripes. There’s a city park on the little plot of land that the commune used to use for leisure activities. Ceresco’s main building, the longhouse, is now a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it apartment complex. The neighborhood around it is decidedly working class. The park is tidy and well appointed. Across Union Street, there are far more signs for Trump than Harris. I don’t know if the MAGA shrine directly facing Ceresco Park was there before Harris came to town or if it was built in reaction. It’s a performance either way.

As for the little white schoolhouse, it used to be downtown, but it’s been moved a few times in the intervening centuries. It’s out on a commercial strip now, next to a car dealership, across the street from a strip mall with a Mexican restaurant and a vape shop. What it lacks in picturesque surroundings, it makes up for in plentiful parking.

The schoolhouse itself is still quite lovely, though. Calling it Rockwellian feels too easy, but the shoe fits. It is both little and white, just big enough to host a small museum about Wisconsin’s grand abolitionist legacy. The building next door used to be a bank, but it’s empty now. Its drive-thru teller window currently houses a miniature version of the schoolhouse. I’m pretty sure that one’s meant for road shows, but for now it just sits awkwardly next to its regular sized doppelgänger. History repeats itself. Sometimes quite literally. Across the street, the vape store has plopped down a couple advertisements for Eagle 20 cigarettes. A bold sans serif typeface implores passing traffic to Buy American. A few blocks down, the Methodist Church has put up a couple signs of its own. I smiled at those ones. Further east, the street narrows as it approaches downtown, close to where the schoolhouse once stood. You’ll know you’ve arrived when you see the Black Lives Matter mural.

Anybody who tells you that Ripon, Wisconsin is a single story is probably trying to sell you something. I suppose that’s true of every place, and every effort to build a better world.

So what do we make, then, of the legacy of the Cerescans? Were they saints or sinners? Did they accomplish a hell of a lot more than the rest of us bleeding hearts? Should they be lauded for the way they attempted to live up to that most basic progressive imposition, the one about thinking globally and acting locally? Or should they be derided as a bunch of privileged White sell-outs, hypocrites whose individualist greed and myopia foreshadowed the ignoble path their once-glorious political movement would walk? Is all this their fault or ours?

Not to disrespect Orwell, but I don’t think that’s actually the interesting question. Every saint is a sinner if you stare at them long enough. Every idealist has a cynical streak. Every dreamer must wrestle with a reality that isn’t all that dream-like.

What’s interesting, for those of us who get to look into the past and imagine it as a mirror, is the patterns. Because of course the Cerescans were imperfect. But what do we gain from laying all the sins committed by future generations on their doorstep?

There is a real lesson in who the Cerescans were at their best— true believers who could have just written op-eds but who tried to be neighbors. A community that might have settled for naval-gazing and self regard but who instead attempted to counter the most pressing moral issues of their day— the ills of capitalism and chattel slavery.

So too is there a a lesson in their failure, in understanding what held them back from creating something much more beautiful. If I’m honest, I recognize their missteps far more than I recognize their strengths: A willingness to compromise with big money and big power. Deliverance from poverty, but only for a select few. A reductive view of what it meant to oppose racism and sexism, one marked more by strident statements against distanced villains than by an excavation of how those hierarchies shaped their own lives. A politics that preached to the choir rather than expanded its aperture of care more generously.

I love them, those deeply flawed Ripon dreamers. But damnit, it’s a complicated love. I cursed them as I drove out of town, not because they failed, but because I wish they offered me an easier lesson. But then, after I cursed them, I muttered a thank you. They tried, is the thing. And now it’s well past our turn to try as well. This time with more of you. This time with a bigger table. This time, with perhaps a little less self-satisfaction and a little more delight in others. I wish they would have figured it out, those Cerescans. But i’m glad that they tried, because I’m glad we’ll never have to be the first to try.

End notes:

Remember when there were SIX Barnraisers Project fall classes to choose from. Well there are only four more to go, so register sooner rather than later. These have been great, and it would be so lovely if you could join us.More details here, and registration here.

Most of you know this, but I wrote a book, The Right Kind of White, which is about a self-righteous son of the Heartland trying to run away from other White people and then trying the community thing. I’m the self-righteous White guy in question, but I don’t think my story is unique to me. If that sounds at all interesting, I think you’ll like it!

Speaking of things I wrote, I forgot to mention that a fun piece I wrote (about a lifetime spent watching Will Smith movies with other White people and pretending I had a Black best friend) is in Electric Literature.

MORE NEWS! I will be talking about that book I wrote (and the broader task of building communities we all deserve) in WASHINGTON DC. on October 17th. Check this line-up out and RSVP here.

Details (still) coming soon for another D.C. event, at the Friends Meeting of Washington on October 20th. It’s at the end of Meeting For Worship, which probably means noonish, but I’ll keep you updated when that’s settled.

Last week’s weekly community discussion might be my favorite we’ve done in a long time. I think I’m gonna keep this format (offering a top five list before opening it up for discussion). Stay tuned for a new one on Thursday. Fun!

Song of the week. Here’s one for the old school abolitionists. “Slavery’s a Hard Foe To Battle.” This version is by Peter Janovsky.

While we’re at it, here’s Bon Iver doing the Battle Cry of Freedom at a Harris-Walz rally in Eau Claire. For my hyper-specific target demographic, his moment was the high point of this particular election season. That’s anothe reason why I’m not putting too much thought into the Harris-Cheney rally. Ask not for whom the campaign panders, because at some point they will pander to all of us.

The entire White Pages Songs of the Week playlist is available on both Apple Music and Spotify.