There are soldiers blocking all roads into Gallup, New Mexico right now

On the three stories white people tell about Indigenous people

Notes: I’m not writing about Ahmaud Arbery in this space (I wrote just a bit here). That’s not to say I’m not in mourning. This just feels like a moment where there is very little that can be said using many words that can’t be said in a few. As I’ve written before, we (in particular white people) have a pattern of paying attention only when it’s too late.

Charles Blow’s words in the Times today are well worth reading though… and, of course, there is work to be done: There are multiple action alerts from the Georgia NAACP, #runwithmaud this weekend and a lifetime of effort for all who dream of justice.

Also: This week’s piece is about the relationship between white and Indigenous communities. While there’s value in digging into that dynamic, you might find that your limited reading time might better be spent hearing from Indigenous people directly. Fair point! I’ll still be out here being white next week! Read some Erdrich or Harjo or Tommy Orange. Follow folks like Gyasi Ross and Twyla Baker and Tara Houska on social media. Support Indian Country Today’s consistently great journalism or binge Rebecca Nagle’s stellar This Land podcast. Get your laughs from the 1491s. Learn from activists (like my sister in this work, Percilla Frizzell) and take action— here is the Navajo Nation’s official Covid-19 relief fund as well as a list of mutual aid efforts for various Southwest tribal nations.

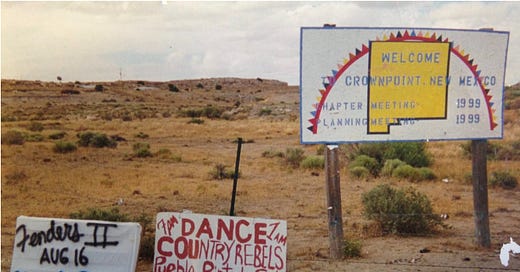

A pretty good prank went down at the school where I used to teach fifth grade. This was in Crownpoint, New Mexico, a hub town on the Eastern edge of the mighty Navajo Nation. The vast majority of folks in Crownpoint are Diné, but there have always been a few white folks hanging around (on account of a hospital and some government offices and some white landowners nearby who got their property checkerboarded off of the Nation).

As the story goes, the old BIA boarding school came to town first. By the time the county school (the one where I’d one day teach) opened up, folks assumed that this brand new shiny building wasn’t for them, so they started calling it “The School For White Children” in Navajo. The name stuck around long after that misconception was cleared up because it was super funny. And so it came to pass that, many years later, the (white-run) school district down in Gallup wanted to put a fancy new sign out front. In a half-hearted effort at cultural relevance, they asked around town if there was a “traditional Navajo name for the school” that they could put on the sign. Multiple folks passed on the jokey colloquial name.

I’ve heard different stories as to whether nobody offered the English translation as a deliberate gotcha or if everybody just assumed that the school district wouldn’t be so dumb as to not Google the meaning of the words they were putting on a large expensive sign (a fair assumption, as the Diné word for white people- Bilagáana- is one of only five Diné words that Rez-adjacent Anglos usually recognize). But yeah… just like how back in 2000 every white guy at the gym had a Mandarin character tattoo that they thought meant, like “Success” but actually said “Toilet,” the district didn’t do any basic due diligence. The sign went up and everybody in town had a good laugh at the out of touch white people down in central office. It was a good day in Crownpoint.

White people don’t talk about Indigenous people often and when we do it’s usually in one of three ways. There are the stories about drunkenness and disfunction and well-deserved-fates. You may not hear these stories muttered out loud if you live far from sizable Native communties, but if you grow up in a white town close to the rez, you heard it all the time— sometimes from the Skoal-stained lips of a local shitkicker but just as likely from the respectable be-khakid Chamber of Commerce member trying to sell you a Subaru or the Homecoming king cracking up his buddies after their team just beat the Arlee Warriors in District 5b play.

Then there are the stories that you hear from the seekers and the transcendental culture-hoppers— the hushed tone reverence with which they talk about Natives as magical, mystical beings stuck in time, useful primarily for the doors to perception or secret pathways to the natural that they can help white people unlock. Depending on your generation, these stories pass from the lips either of Santa Fe crystal chasers and dream catcher hoarders or from Instagram-fueled ayuahasca seekers or peyote-curious Burning Men and Women. The tellers may have changed from generation-to-generation, but the remarkably flowy, breathable fabrics they wear remain the same.

Most of all, though, are the stories of pity. We all tell these stories. We know that we’re supposed to feel badly about genocide and land theft. We know that we should perform a look of deeply constipated Christian concern when we hear the words “Pine Ridge” because that is a place where we’re told where people are very poor and very miserable. Perhaps you can speak to this sadness first-hand because your church youth group took a caravan of white vans there to paint houses one summer. According to approximately 1000 college admissions essays per year, that’s a particularly affecting experience. The bad news is that these stories really bum us out. The good news is that we usually only think about them for a few minutes at a time, long enough to change our Facebook location to “Standing Rock” (remember when everybody did that?) and then go back to our lives.

It shouldn’t be a surprise that we are stuck with such limited, dehumanizing stories of Indigenous lives. When your country’s history is so deeply dependent on the attempted termination of hundreds of societies and millions of human lives, it is deeply inconvenient when, hundreds of years later, those people are still here. To accept contemporary Indigenous humanity in all its fullness and complexity is to accept Indigenous sovereignty which is to accept that perhaps the land on which we are living and resources we are using that aren’t actually ours and well… to take action on that would mess up a whole lot of things that are currently nice and convenient for the rest of us. It’s so much easier if they are one-dimensional mascots— be they drunken criminal monsters or trippy spiritual superheroes or forlorn powerless sin-eaters upon whom we can place our guilt

I’m writing this in a week when Indigenous stories have, at least moderately, peaked their way into a broader, whiter consciousness. Perhaps you heard that earlier this week there was a National Day of Awareness for Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and girls. Perhaps you’re aware that, weeks after it was promised (and for the dumbest possible reasons), tribes finally started receiving money from the CARES Act this week. Most of all, though, you likely heard that Gallup, New Mexico is under lock down, that there are soldiers literally stationed outside that dusty railroad town that lives in a permanent state of love-hate codependence with both Dinétah and neighboring pueblos. If you heard that, it’s likely that you also heard that the Coronavirus is on a ripsaw path of destruction across the Navajo Nation, that places like Crownpoint are getting hit harder than virtually any other area of the country.

I wish so badly this wasn’t the first story you were hearing about Gallup, about Crownpoint, about the Navajo Nation. It’s such a brilliant, flawed, gorgeous, befuddling mess of a place. It is home to the largest collection of superlatives per capita of anywhere I’ve ever lived. There’s no better weaver in the world than your one friend’s Grandma, no funnier human being than your other friend’s Auntie who works at the Post Office. There are at least three dudes who can fix a truck better than any auto shop around and two more whose bald-faced lies about their abilities to do so are, themselves, some of the best lies in the world. And oh my God there are no high school gyms louder, no better places to watch some of the shortest power forwards in the world play the fastest basketball you’ve ever seen.

It ain’t all superlatives, of course. Rez towns like Crownpoint, border towns like Gallup and urban Native enclaves like Albuquerque are places where people fall in love but also where they break up acrimoniously. They are places were people start businesses, launch political campaigns, get screwed by the last set of guys who launched political campaigns, make colossal mistakes, lie and cheat and steal, give generously, laugh heartily, have good days and bad days, piss each other off and hold each other up. There’s plenty of tragedy, plenty of tears, plenty of laughs and, like all human communities, plenty of blame to go around.

And oh goodness, at moments like this, when Dinétah is under attack from another outside invader, it’s right to feel awful, to call attention to the tragedy, to offer solidarity in any way possible. We should feel badly. This virus wouldn’t be devastating Navajo lands right now if white America hadn’t spent hundreds of years clearing the runway for its deadly arrival (viruses take a real liking to places with substandard, overcrowded housing and lack of clean, running water). But if the only moment that Indigenous stories and lives matter is when their trauma is on display in particularly harrowing ways, we’ll be back right here before too long. Our sympathy will be as destructive as the Pilsner-breathed slurs of the border town tough guy or the cartoonish culture-aping of the turquoise-chasers.

I began this article with a list of Indigenous people whose voices I think are worth paying attention to. You’ve likely seen lists like this before (as well as parallel lists of Black voices and Latinx voices and Queer voices, etc., etc., etc.) and it’s easy to experience them just as guilt-appeasing box-checking (picture Bart Simpson writing “I should listen to diverse voices, I should listen to diverse voices” over and over and over again on the chalkboard). But here’s why listening to Indigenous people, particularly if you aren’t lucky enough to have close Indigenous relationships, matters so much: If part of why we’re stuck in this place is a constant flattening of Indigeneity solely to tragedy, the more that white America learns complex, three-dimensional Native stories, the more that we can build political will for reparations and treaty rights and Indigenous sovereignty.

Here’s the deeper truth that I’ve been circling around here. Our government’s continued willingness to ignore, lie to and leave for dead Indigenous nations isn’t just because people in power don’t actually care about Native people as full human beings. It’s because they know, deep down, that you don’t either. And it’s going to take more than just feeling sorry for Indigenous people occasionally to change that. It’ll take embracing a story of Indigenous humanity and potential that is deep enough and complex enough that you truly believe that this continent we share will be stronger if Indigenous nations were given the opportunity to fully craft their futures here, regardless of what it means for U.S. power and property.

Crownpoint, New Mexico isn’t just a place where tragedy happens. It’s a place where human beings have organized to fight off uranium mines. It’s a place where local artists founded their own rug market, figuring out how to make the Santa Fe art world come to them rather than having to truck their stuff over to predatory dealers. And most of all, it’s a place where folks are clever enough to know that the long-con payoff of your bumbling white school district putting up a “School For White Children” sign is going to be so much funnier than any short-term laugh line would have been.

Please take action to support the Navajo Nation and other communities in this moment. You’ll see a brief list of how to do so below. And then please don’t stop. There are voices to listen to, not as tokens, but as individuals who can help unflatten a whole bunch of two-dimensional narratives. Your job is to keep listening until you stop feeling sympathy and instead are filled with excitement and imagination— a new energy for what could be true on this land if it could be more fully crafted again by Indigenous minds.

End notes: Again, here is the Navajo Nation’s official Covid-19 relief fund as well as a list of mutual aid efforts for various Southwest tribal nations.

This week’s music: “Shiprock Girl” by Stateline. And, if you’re not hip to the never-ending country rock rez touring circuit, do yourself a favor and read this piece. Fenders II forever.