There have been and will be so many articles this week. There will be so many attempts to parse what has and hasn’t changed since George Floyd was murdered and we spent a summer marching in the streets. They will mostly say the same thing. That’s not a criticism; there are only so many ways you can say “mostly things haven’t changed.”

I don’t want to write about movement failure. I don’t want to admonish protesters for failing to undo thousands of years of history in the blink of a pandemic summer. I do want a better world though, which makes me curious about what has and hasn’t happened in the past year.

Do you remember back when it felt like everything might actually change on a dime, when every day there was a new headline about another monument toppling? Do you remember how they started off small and largely inconsequential, like changing the name of the pancake bottle? Do you remember how the protests, which we had been conditioned to expect would peter out after a few days, instead kept growing and growing and the announcements got less silly and then all of a sudden there was a crowd of Minneapolis council members on a stage in a park and they said that they would actually defund their police department?

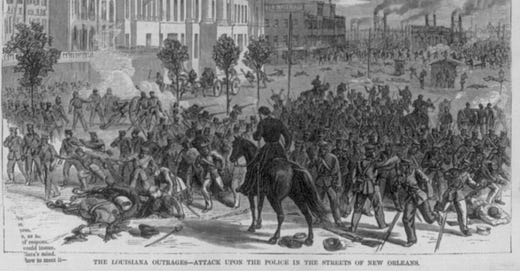

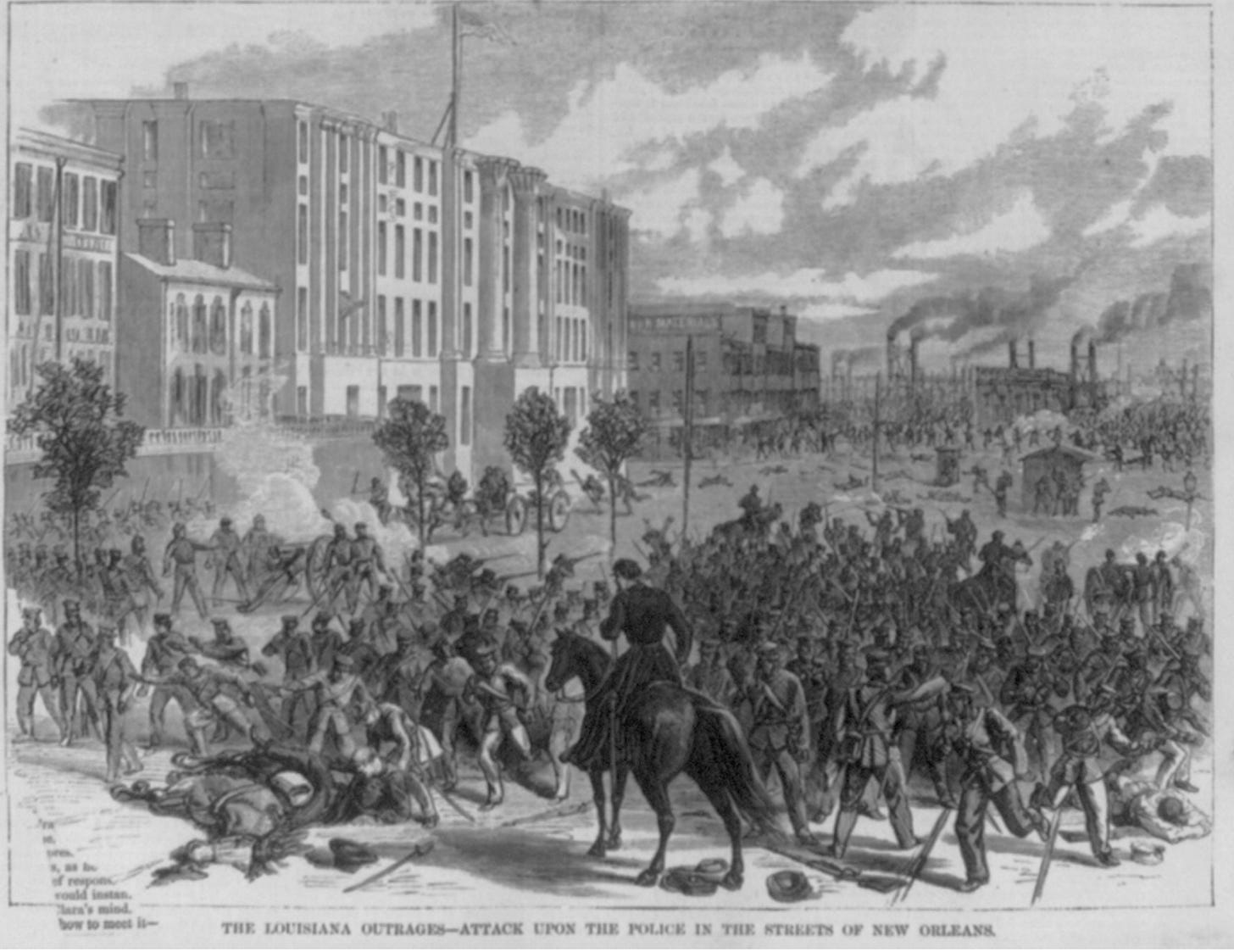

They ended up backsliding, but you know that. Fear not, enemies of cancel culture. Minneapolis cops weren’t canceled after all. Hell, the television show Cops wasn’t even canceled. Again, this isn’t another piece just admonishing us for not changing the world. But damn. One step forward, two steps back. Reconstruction. Jim Crow. Civil Rights Act. Southern Strategy. Why are we always so predictable?

You have probably seen the polls, the ones that show white support for Black Lives Matter suddenly ping-ponging up and then eventually crashing down again. If you prefer to veer towards cynicism, to believe that social change is impossible and that the marriage of white people and white supremacy will never be severed, you can find all the evidence you need in that cursed electrocardiogram of a line graph.

There’s a mural near my house, one of dozens that were painted last summer. It boldly proclaims “this is a movement, not a moment.” I don’t like walking by it. Not one bit. Whenever I see it, I feel a wellspring of nihilism that I’d prefer to pretend doesn’t live inside me. “It wasn’t a moment, damnit! White America will always make it just a moment!” It is easy to get smug and judgmental. It’s easy to make the same dumb jokes about black Instagram squares that everybody else has already made and to congratulate myself because I just self-administered my own “did I backslide?” test and passed with flying colors.

But what if there is a lesson in the last year beyond the easy nihilism?

What if all the change that didn’t come to fruition, rather than revealing the failure of movements, instead offers greater clarity as to the work still to be done? What if there is as valuable a lesson in the slow backsliding as there is in the big bold flashpoints?

If the problem of white supremacy in 2021 was one of malevolent bias or lack of awareness or “white silence” then the most widespread and long-lasting protest movement of our lifetime would have been enough. We had Mitt Romney out here Black Lives Mattering. We had a very large plaza devoted to Black Lives Mattering in our nation’s increasingly less and less Black Capitol City. We had NBA players with league-approved justice-adjacent slogans on their jerseys. That’s Susan G. Komen levels of awareness!

As it turns out, when you invent the idea of a benighted racial group and then give that group thousands of years of access not just to power and wealth but every possible theological, philosophical and pseudo-scientific justification to believe that they actually deserve it, that group is extremely resistant to change.

The problem is not that white people need to hold less hate in our hearts. The problem is not that we need to become more aware, that salvation lies in the next perfect book on our reading list. The problem isn’t even that we haven’t listened enough to Black or Brown or Indigenous voices or centered other people’s leadership. All that is necessary, but insufficient.

The problem is that we know, us white people, that we haven’t been playing for the righteous team. We all feel it intrinsically, even when we vehemently deny it (hell, especially in the moments that we vehemently deny it, for what is stubborn self-righteousness if not self-doubt combusting). We know that we’re accomplices to the most evil, malevolent project in the history of humanity. We know that we can’t help undo that project without being willing to recalibrate our relationship to so many things— to wealth, to power, to the stories we’ve told ourselves, to the shortcuts we’ve taken to “comfort” and “security.”

Our brains, of course, are not built to process that level of cognitive dissonance, so of course as soon as we start to consider what it would mean to actually build a better world, we backslide. We seek out the comforting, narcotizing voices that will assure us that nothing is wrong with us, that the problem is the demands others are making of us.

If you are reading this and you are a good progressive white person and you didn’t tell a pollster one day that you supported Black Lives Matter only to backtrack that a few months later, you will likely be nodding along at that last sentence. What a provocative and accurate assessment of those sad white people who turn on Tucker Carlson every night so that he can lull them to sleep with comfortings lie about how Ibram X. Kendi wants to steal their children!

I’m not talking about a “them,” though. There is no “them” in whiteness. That might be the most narcotizing story at all. At some point in the last year, all of us had a moment when we considered that perhaps we needed to do more— that we shouldn’t have decamped to the suburbs in search of “good schools,” that perhaps our job does do more harm than good in the world and no amount of “Our Commitment To Antiracism” statements will change that, that our law enforcement spouse may very well be a good person but that doesn’t mean that the broader system in which they work isn’t monumentally anti-human, that the profits from our last house sale actually don’t belong to us but should go to a reparations fund, that change is necessary as long as it doesn’t impact our marginal tax rate, that the book club that disbanded after we read the epilogue and agreed “wow, it’s just so complicated” actually should have done something.

We all had those moments. We considered them. They scared us. And then we listened to a voice, perhaps internal, perhaps external, that told us that it was ok to stop, that the path of least resistance was justified, that we could live with the compromise.

And if that’s all true, it means that we actually have the same story, us white people. We walked up to the pool, considered jumping in, and then turned back around. And if we have the same story, well, that means that we’re pretty much stuck with each other. It means we need each other. It means that none of us can figure out our way forward without each other.

Nobody asked to be a part of a community bonded by their thousands-plus-year legacy of generational oppressiveness. It’s understandable that so many white people want so desperately to run as far away from the rest of us as possible. We seek absolution in having Black partners or children, in working at do-goodery nonprofits, in living in putatively pluralistic cities rather than “backwards” small towns, in not being afraid to say bolder statements about abolishing the police than our more “fragile” skinfolk, in always being the one to remember the land acknowledgment.

But, a year removed from the longest (but by no means first) National Reckoning on Race in my lifetime, here’s the bad news: You can and should spend as much time listening to, learning from, elevating and loving Black, Brown and Indigenous folks. You shouldn’t live in a white bubble. But none of that won’t save you.

If it only took yelling at each other more stridently, we would have arrived at liberation right now. Instead, what we’ve learned is that at every moment of progress, there will be a powerful gravitational pull towards white backsliding. There will be a cottage industry of grifters pulling us back into oppressive complacency. The stories that comfort us will rise back to the foreground.

If we want to be part of building something different, far from turning away from other white people, we need to pull ourselves closer. We need to build relationships strong enough for us to admit to our fears, to the stories that we can’t give up, to the actions we’re afraid of taking. And then, in spaces rooted in trust and mutuality, we need to push each other forward. We need to give ourselves a chance to mourn the loss of our stories, but not permission to be drugged by them in perpetuity.

I am going on a walk later today. I’m gonna walk past that mural. It will remind me again, “this is a movement, not a moment.” I will read it again not with nihilism but with purpose. I will perhaps realize, this time around, that it was never a promise, that it was always an invitation. And invitations are always beautiful.

End note: I always feel torn about sharing links to my own work, but if you’re new here and all this sounds intriguing but you’re also a little mad at me for not saying more about the “how,” I run an organization called The Barnraisers project and this is all we do. Feel free to either reach out and ask me questions or to sign up for an upcoming organizing training cohort. The next one is still TBD, but it’ll be sometime in the late summer, early fall.

There is something crucial, and not at all delusional, about living the future you want right now. Putting the movement inside the moment. Placing the furthest implications of a liberatory practice within the lived intimacy of this: this day, this hour, this minute, this second.

Ugh, this was the think piece about the Floyd murder that I needed to read this week (but didn't really want to).