I didn’t write one of those “talking to your family at Thanksgiving” pieces this year but if that’s what you’d like, here’s what I wrote last year.

ALSO: I’ve changed platforms. I’m on substack now. Is it better for you? Worse? Let me know.

OH, THIS TOO: For those of you who want a Howard County Schools update (it’s mostly good news!)

That’s how it starts

I’m in a coffee shop. You know this coffee shop. Increasingly, for a very specific demographic of which I am absolutely a member, it is the only coffee shop. The design is minimalist (this one has hexagonal tiles; yours likely has Edison Bulbs). There are tasting notes. There is plenty of oat milk. There is no Sweet and Low. The soundtrack is borrowed whole cloth from a 2007 Oberlin co-op make out mix (“Autumn Sweater” segueing into “All My Friends” just as the Good Lord intended). I’m not complaining. Oat milk rules and “All My Friends” still slaps.

I am an easy mark for this coffee shop. I’ve been to it in at least fifteen different cities. Brooklyn. Chicago. Los Angeles. Missoula. Rockford. Baton Rouge. You get the point.

I haven’t been to Rapid City in many years but I’m told that the one there is called harriet and oak because of course it is. According to yelp, the açaí bowl there is amazing.

And if it's crowded, all the better

Because we know we're gonna be up late

But if you're worried about the weather

Then you picked the wrong place to stay

That's how it starts

Custer died for your graffiti alley

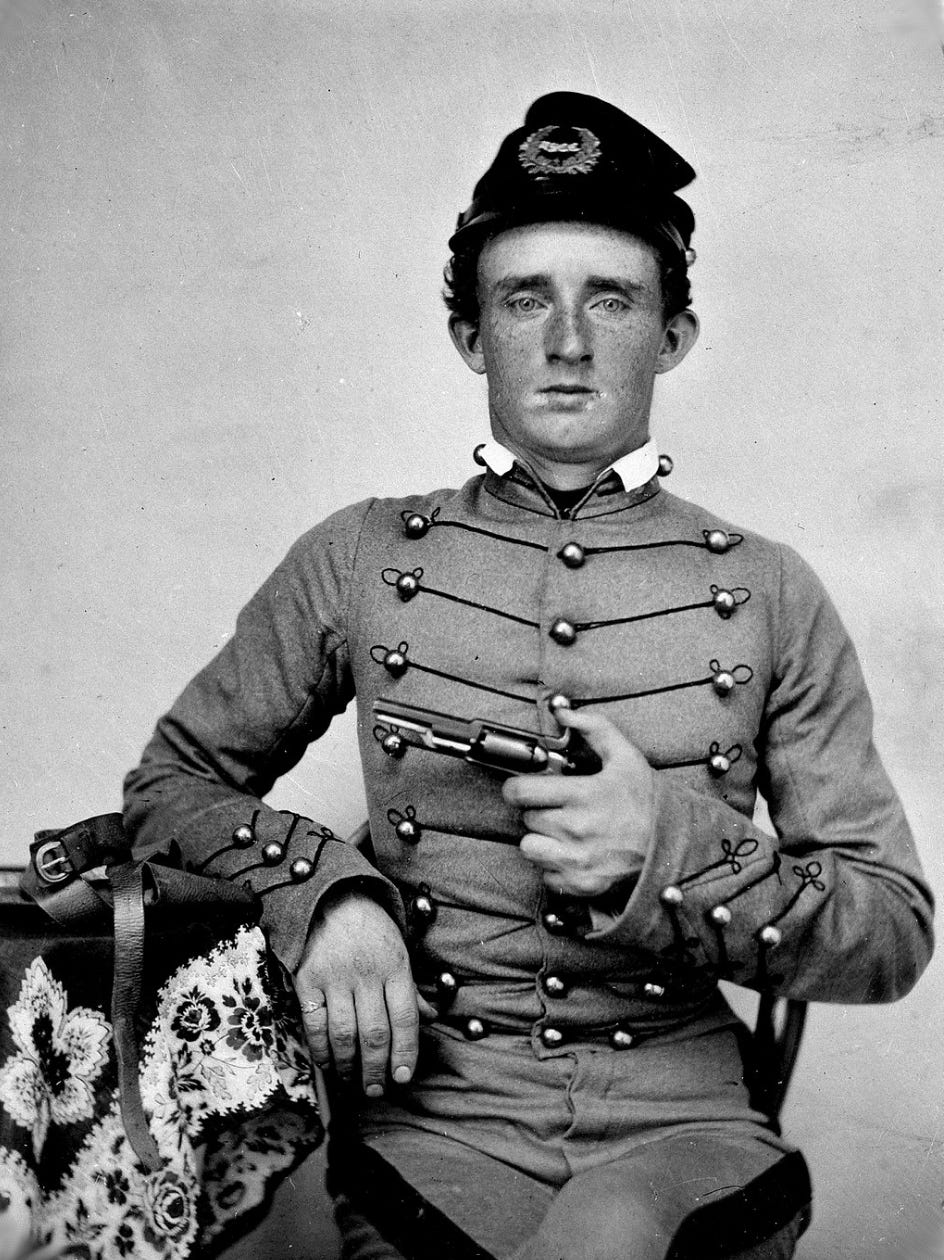

General George Armstrong Custer was bad at many things. He was, of course, an absolute wastewater treatment plant of a moral being, but he was also an awful student (last in his class) and a mediocre (though frequently quite lucky) military commander.

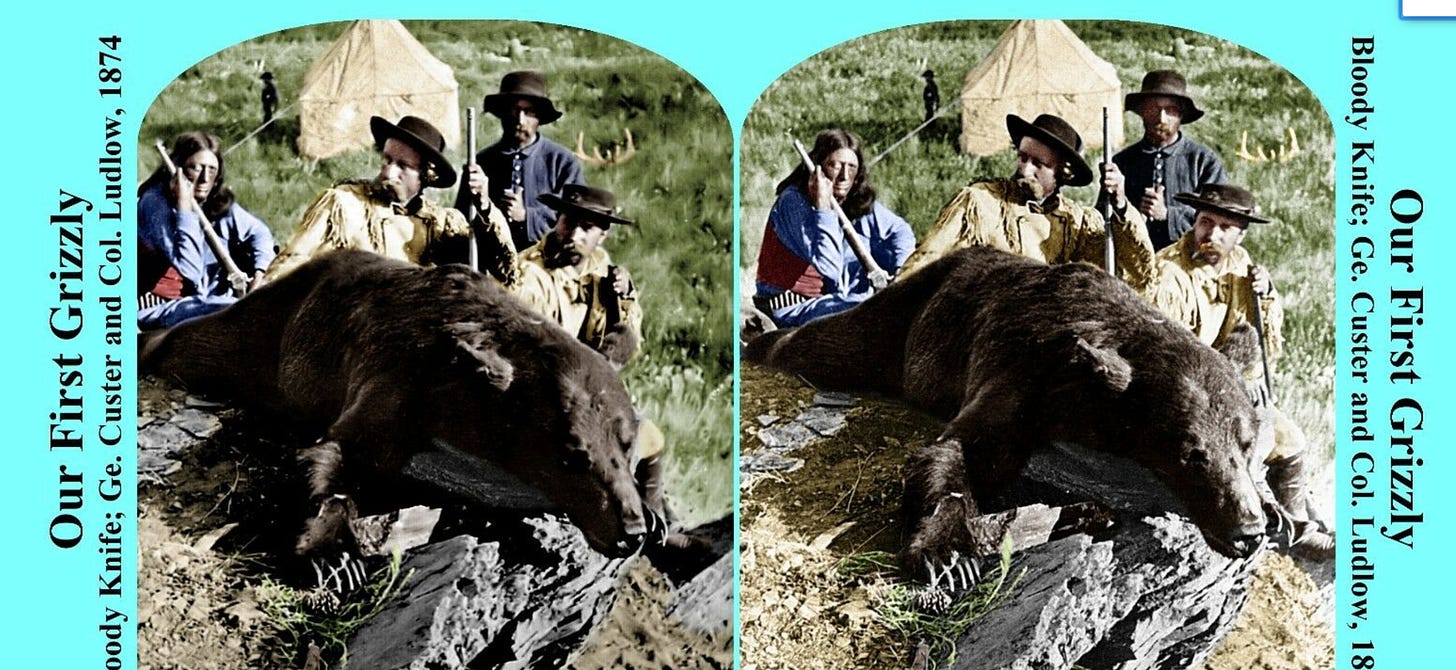

He was, however, quite good at personal myth-making. It’s why, even while leading a gold-seeking expedition to the Black Hills, he perfumed his hair with cinnamon and wore a black lace uniform with coils of gold. It’s why he commissioned a photographer to accompany him West. And it’s why he triggered a gold rush by sending word back about the riches to be found in the Black Hills when he had, at the time of his proclamation, only found small traces of placer gold.

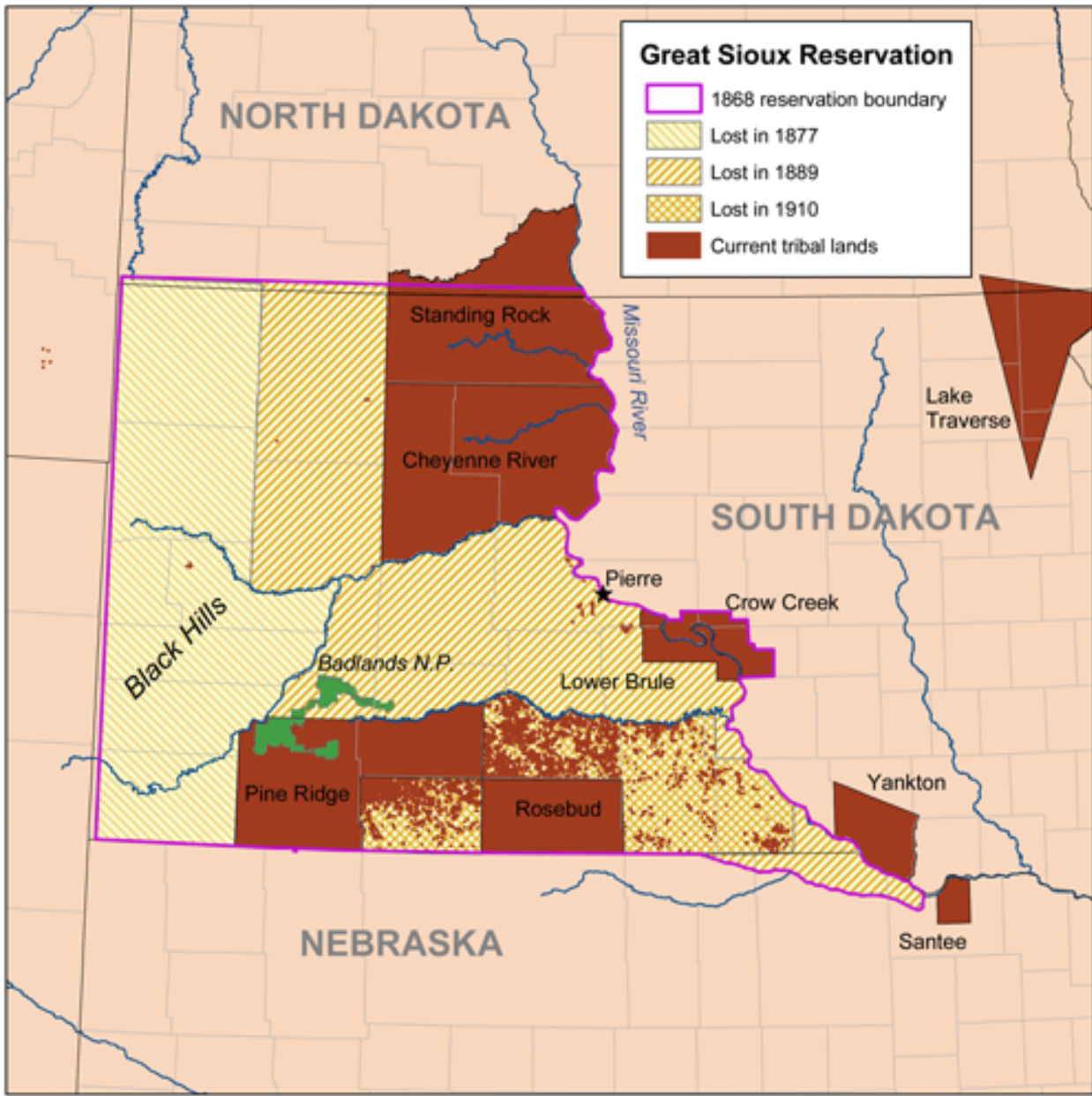

Here’s what happens when you trigger a gold rush: White people flood into the Black Hills by the thousands. Technically, this should create a problem, as it means that a large chunk of land that the U.S. government had deemed sufficiently undesirable so as to be recognized as Sioux territory suddenly becomes quite desirable indeed. Fortunately, you can simply break the treaties you made with various Sioux nations. If you are then comfortable with weathering some subsequent unpleasantness (read: wars) you can come out on the other end with all the land and gold you want. Custer won’t survive those wars, but a century of hagiography will ensure his legacy remains strong.

And then, you can build things! Like Presidential head mountain carvings! And a mid-sized city whose downtown, by all accounts, has redeveloped quite nicely. You should see the city-sanctioned graffiti alley. You should try the craft beer. You should definitely get an açaí bowl.

This is not very complicated

Settler colonialism is a hell of a drug, in no small part because the moves are easy to master. The first step, of course, is to be white. The second step is to decide that you’d like a certain property, ideally for the purposes of making money. Then, you tell yourself and your children and your grandchildren whatever story is necessary about the people who previously resided on that property so as to justify some good old fashioned thieving.

These moves were invented to steal Indigenous peoples’ land, but since we white people have mastered the form we’ve applied it not just to tribal nations but Black and Brown people as well. Nowadays, the property we often want is the urban neighborhoods that two generations ago were so undesirable that we forced Black folks in particular to live there (through redlining and blockbusting and restrictive deeds) but which we’ve since discovered to be rich with the twenty-first century equivalent of gold ore (exposed brick, original fixtures).

You know all this, of course. And you likely feel very badly about it— both the mass land theft/genocide and the eviction notice/shiny condos. But here’s where it gets interesting. By all accounts, these are situations where the major policy remedies that correct for past/ongoing injustice are pretty clear. Curiously though, the moves us-white-people-who-feel-badly-about-the-whole-situation make are often much less about those remedies than we are about showing off just how badly we feel.

It comes apart

Like it does in bad films

Except the part

Where the moral kicks in

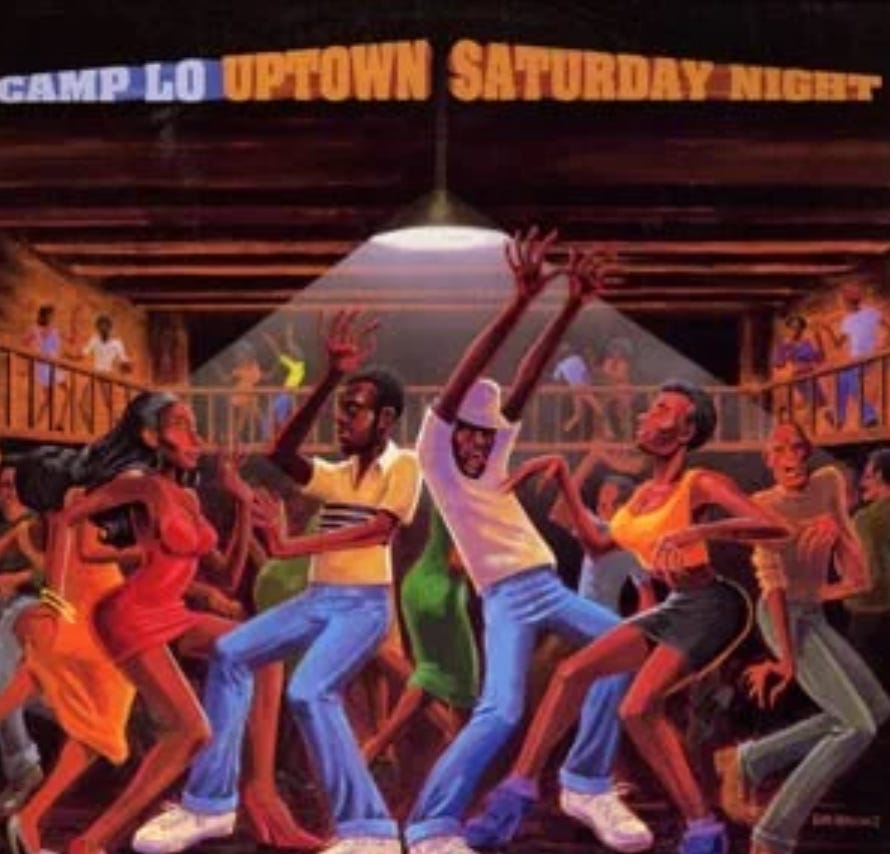

Uptown Saturday Night is a perfect record

No really, it’s so good. It’s a 1990s party record about 1970s pop culture that still sounds like the best thing out right now. It’s also an incredible signifier. Just like how an LCD Soundsystem track over The Only Coffeeshop’s speakers serves as a bat signal to my demographic of upwardly mobile Pale-Americans, so too is Camp Lo an indomitable choice if you want your bar/restaurant to scream “this is a cool hangout for hip Black and Brown people of a certain age and income bracket.”

Camp Lo plays a bit part in a story you’ve likely heard— about a bar/restaurant in gentrifying Crown Heights, Brooklyn called Summerhill. The place is closed now, but it lived its life fully in the public eye. It first made headlines when its white Canadian owner bragged about how she was retaining her property’s original “bullet holes” and would be serving wine in brown paper bags. Protests ensued, because, well, that’s super messed up. The protests were Black-led but majority white because, well, they took place in Brooklyn in 2017.

Summerhill’s second act in the public eye came the following year, when a This American Life producer investigated why the once-besieged establishment was now packed to the gills… with Black people. The answer was either, depending on who told the story, one of a white owner giving up power to a Crown Heights native or of a cynical exercise in window-dressing/myth-making. In short, after the initial uproar the owner made her executive chef, a Black guy, a partner in the restaurant. He, in turn, became the public face of Summerhill and marketed the heck out of the place- his Instagram posts were on point, the DJs he hired played exactly the right stuff (which is how Camp Lo got their first ever shout out on This American Life). Some of the new patrons counter-attacked the protestors on social media, calling them the real gentrifiers.

It all sounds super ugly and messy and I’m actually not bringing it up to re-litigate the dust-up. I mean, the place is closed now. The gentrification of Crown Heights marches forward. But isn’t it wild that this single restaurant captured so much attention? Why is it that I can tell you the names of multiple players in L’Affaire Summerhill but I can’t tell you the names of any of the developers or city council members most responsible for displacement in the neighborhood?

Our obsession with the bit parts and players of gentrification is generally unhelpful but totally logical. As Peter Moskowitz argues in the terrific anti-gentrification tome How To Kill A City- that’s the part we see (and for those of us who frequent The Only Coffeeshop, that’s the part about which we feel guilty). That’s the way oppression works— no matter how bad things look on the surface, the more insidious stuff is always hidden from view. Per Moskowitz “the policies that cause cities to gentrify are crafted in the offices of real estate moguls and in the halls of city government. The coffee shop is the tip of the iceberg.”

I’m sure that a lot of the fortune-seekers who flooded into the Black Hills were super annoying. That doesn’t mean they weren’t still pawns in a larger game with a bigger villain.

It is reductive and insulting to merely call the Black Hills “a piece of property,” as I did above. It is sacred land for multiple Indigenous nations. It’s so sacred, in fact, that the seven member states of the Sioux Nation are, to this day, actively rejecting over a billion dollars in settlement money from the U.S. government (it took until 1980 for courts to force the U.S. admit that we, collectively, were and are the worst). They’re holding out, justifiably, for what they’re actually owed: Rights to their land.

This is what I mean when I say that we’re dealing with issues where the policy prescriptions are actually pretty open and shut: Tribal nations had land and life stolen from them. These nations deserve support for whatever their reparative demands might be. It’s ok that those demands can and do differ depending on the Indigenous nation doing the negotiating: The Duwamish tribe in Seattle, for example, actively endorses a city-wide reparations fund. Meanwhile, many of the Siouxan nations (particularly the Oglala Lakota) are actively trying to purchase parcels of the Black Hills. While it might seem like there aren’t easy entry-points for outsiders in that campaign, since the strategy hinges on ongoing economic development in the Lakota community, support for initiatives like the Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation can go a long way.

Likewise, if you’re worried about gentrification in your neighborhood, neither your patronage nor your one-person boycott of the particularly twee coffeeshop on your block is going to move the needle one way or another. What will, though is finding and supporting your nearest tenants-rights organization (they’ll surely know where the bodies are buried, what developers are raking in TIF funding and what low-income communities in your town are actually dreaming for themselves).

That must sound obvious. But it isn’t what we’re doing.

The Revolution Won’t Be Hurriedly Googled

Here’s a scene I’ve witnessed a few times. You’re at a convening full of good social justice-y people. At some point, the organizers realize that they forgot to do “land acknowledgement.” Somebody grabs their phone, googles the same website that we all use and rattles off a list of Indigenous nation names reverentially. Folks then get back to the business of the day, never mentioning the moment (or the nations) again. One time I heard a facilitator even let out an audible sigh of relief when the process was complete— the rhetorically bad space had been cleansed.

Listen, land acknowledgment is all well and good. I understand why many Indigenous activists support it tactically as a bridge towards broader support for tribal sovereignty. But I’ve never been in a majority white space where that bridge actually leads anywhere— it’s an item on a checklist that reassures participants that they belong to a good community, that they’re freed from any unpleasant feelings. We’re not really doing it for Indigenous sovereignty; we’re doing it for us. Now, if those same organizations were in long-term contact with the Indigenous nations whose names they rattled off, if they offered a specific means of supporting an ongoing reparative political project, that’d be different.

It doesn’t feel good to live on stolen land, just like it doesn’t feel good to know that your country was built on chattel slavery. It makes sense to feel guilty while earnestly enjoying a very expensive cup of coffee and knowing that you too are a pawn in a bigger game that hurts people. And I understand that there are things we will always do primarily for guilt appeasement (it’s 80% of the reason I return any emails most days). The problem comes when we confuse “the things we do to cope with our guilt” for “anti-racist action.” For those of us who are white, if we earnestly want communities other than ours to win, then let’s fight for things that actually tip the scales toward justice. Otherwise all we’re doing is play-acting to make ourselves feel and look better. We’re alternately picketing or defending Summerhill, we’re frantically googling our way to guilt appeasement, we’re perfuming our hair in cinnamon.

We’re panning for placer gold and calling it a mother lode.

You spent the first five years trying to get with the plan

And the next five years trying to be with your friends againOh, you're talking forty-five turns just as fast as you can

Yeah, I know it gets tired, but it's better when we pretend