This is the only way this story could have ended

Until we (as white people) get past our desire for quick-fix racial justice solutions, we'll never help build a better world

Note: I often worry that I repeat myself in this space. This week, I’m sure of it. I promise that I would write something new if (unfortunately) this particular message didn’t bear repeating. I hope that, for long-time readers, this at least comes at my common refrain in a slightly different key. But yes, we have been here before. The details of the moment are slightly different. The fact that I’m quoting Stokely Carmichael again remains the same. Thanks for your patience.

Grand juries are collections of human beings tasked with a specific job. They decide whether or not to bring criminal charges against other human beings. That’s all they do.

Criminal charges are, in turn, one of the only ideas we’ve developed as a society for what accountability for wrongdoing might look like. Like all things, the whole affair is wrapped up in a big pile of cultural assumptions: Who is a criminal vs. who is a helper? What is the law and who is it designed to protect? What are police for and who do they serve? What is a city and who is allowed to live there in peace? Who is permitted the illusion of a full, vibrant life and who can be sacrificed to make that illusion possible? To what do we owe each other as human beings: healing and reparations or separation and punishment?

There was no version of the news from the Jefferson County Grand Jury today that would have changed any of that cultural logic. Perhaps there are verdicts that would have offered Breonna Taylor’s family a more humane acknowledgement that our country failed their daughter. Perhaps there are news conferences that would have caused slightly less additional pain for millions of Black people. But in the broadest sense, there was only one possible outcome possible today and so here we are.

The notion that the system isn’t broken, that it’s doing precisely what it was designed to do, isn’t news, of course, to Black or Brown or Indigenous people. By this point, it’s also been accepted by socially conscious white people as one of the many “right answers” we recognize from various DEI trainings or online explainers.

But we don’t really act like we believe that, do we?

We are addicted to the quick fix, to the band-aid on the flesh wound, the tapestry hung haphazardly over the bare electrical wires. We marched this summer! We made #arrestthecopswhokilledbreonnataylor into a meme! We bragged about the friendships or familial relationships we ended over differences in political opinion! We hoped beyond hope that an entire nation’s commitment to civil liberties could hinge on whether a single 87-year-old woman stayed alive or not!

And perhaps we’ve learned enough not to be surprised when none of that makes a difference. It remains unclear, though, after witnessing the collective entropy of white supremacy pulling the football out from America’s feet for the millionth time, if we’re finally ready to do something differently.

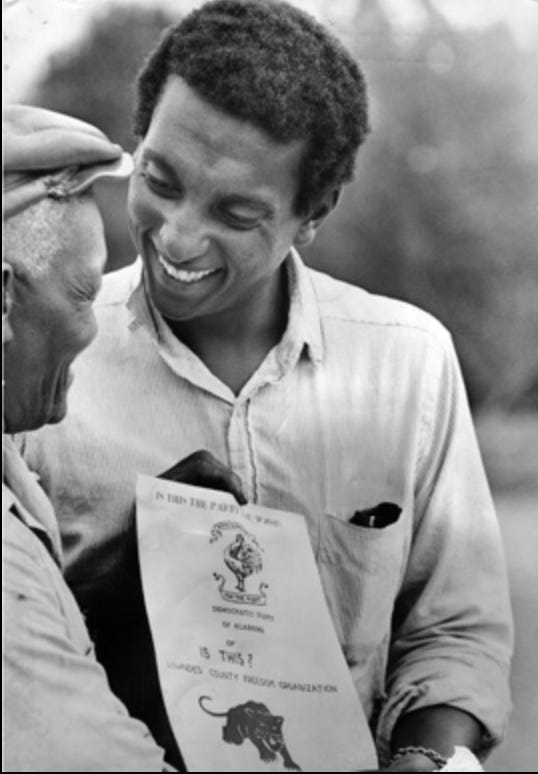

The question is, can the white activist not try to be a Pepsi generation who comes alive in the black community, but can he be a man who's willing to move into the white community and start organizing where the organization is needed? Can he do that? The question is, can the white society, or the white activist disassociate himself with two clowns who waste time parrying with each other rather than talking about the problems that are facing people in this state? Can you disassociate yourself with those clowns and start to build new institutions that will eliminate all idiots like them?

-Stokely Carmichael. Berkeley, CA (1966)

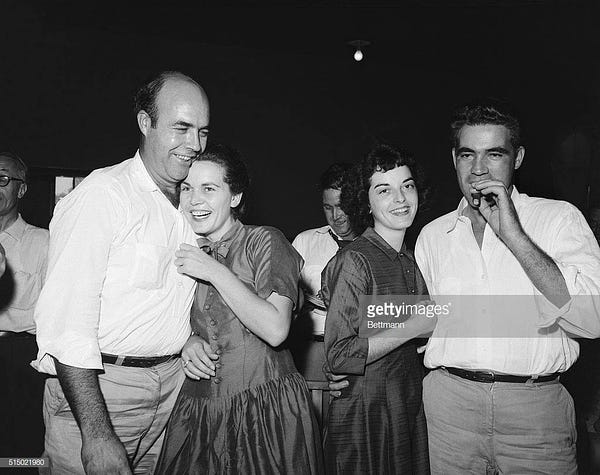

What’s often lost in the history of the late-1960s Black nationalist moment was that there was a second charge issued alongside the demand for Black Power. Leaders like Stokely Carmichael and Fred Hampton believed so deeply in the urgency of organizing in white communities that they literally supported and bankrolled white activists in the South and Upper Midwest. The problem was, white people’s attention spans drifted quickly when they were asked to do something more uncomfortable than show up at street protests. The white-led Students For a Democratic Society backtracked from their initial commitment to co-fund efforts in working class white neighborhoods when it became clear that the work would be generational, not immediate. White campus activists who came down South with Freedom Rider dreams balked when Anne and Carl Braden encouraged them to go back to their homes and work there. As Anne Braden once complained to fellow organizer Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz about other white leftists, “They just didn’t like white people! You can’t organize people if you don’t like them!”

And so the pattern continued for another fifty years. We never did get around to building an organizing infrastructure in white communities, so the underlying cultural logic of white America never changed. In the meantime, us good conscious white people showed up for individual moments where we could feel like heroes but then treated ourselves to a nice long break after we got our social consciousness fix. We marched against apartheid in South Africa. We voted for Obama. We made a status update for Trayvon. We updated it for Mike Brown and Philandro Castile and Alton Sterling. We may have moved from our keyboards to the streets for George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, but the overall pattern remained the same.

If you are white and you aren’t sure what to do about all this, here is the good news. The problem isn’t a shortage of work to be done. It’s that an entire system has been built to sustain our social position. I recognize that very few people intrinsically think of themselves as organizers, but organizing is merely the art of conversation and relationship-building applied to the project of collective cultural change. And if you’re ready to build relationships and have conversations, then thank goodness because there are literally dozens of opportunities for you to do so with your neighbors right now:

-Conversations about your relationship to law enforcement, about what we’ve assumed is necessary to keep “us” safe and what it would look like to build more humane alternatives.

-Conversations about your relationship to taxation and pitching in for the public good. Breonna Taylor is dead not merely because of the individual actions of police officers, but a drive by the city of Louisville to gentrify her neighborhood. That drive, in turn, was fueled by the fact that cites are overly reliant on property taxes to fund basic services (including, of course, bloated police departments).

-Relatedly, conversations about our relationship to housing and “housing values”— about where we live, whom we allow to live next to us, where we assume we’re allowed to move regardless of the repercussions, of our expectations for how well the services in the places we live work “for us” specifically.

-Conversations about schools, about the ways in which we hold public school systems hostage by either moving our kids to private schools or well-healed suburbs or shuffling them through a city’s small handful of desirable magnet programs or taking over PTAs when we feel the system isn’t working well enough for our own white kids.

-Conversations about the companies where we work— including the cool, with-it ones who gave employees Juneteenth off this year— and whether they are operating in the public good or not (in particular in regard to willingness to be fairly taxed and operate in accordance with what would be of value for society as a whole rather than their own bottom-line).

-Conversations about our elected officials and what bravery we truly should expect from them, about whether we’re ready to have our government lead the charge for reparations and reparative justice and whether we’re willing to vote out any elected representatives who offer us anything less.

-Conversations about our relationships to each other as neighbors— whether we are committed to building the bonds of caring and mutuality that we’ll need if we want to build a world beyond the competition and scarcity preached to us by white supremacy.

There is no shortcut to beloved community. And though a more beautiful world needs to be built from the voices and dreams and leadership of those who’ve been denied agency in our current world, it will find its greatest and most persistent road blocks in our white communities. That’s where our work was 50 years ago and, because we ignored it then, that’s where our work remains today.

We are a nation of wind-up toys. The reason we keep walking in this same direction is that every time we’re picked up and re-set, we demand to be placed down in exactly the same formation. We won’t move in a different direction until we decide to do so. Others won’t join us until we build the path for them to walk with us.

When you wake up tomorrow, which direction are you prepared to walk? More importantly, to whom are you willing to reach out a hand?

Note: If you’re interested in learning more about how to organize white people for racial justice and collective liberation, you can find out more information at The Barnraisers Project website.