Trying to be curious about an incurious book

An essay (and a letter) written the morning after I read Nellie Bowles' "Morning After The Revolution"

Let’s be perfectly clear. I’m sure that Nellie Bowles doesn’t care whether or not I enjoyed her new book, Morning After The Revolution. I’m just a dad in Milwaukee. Last Friday, I volunteered for lunch duty at my kids’ elementary school and a couple of first graders pointed at me and yelled “STRANGER!” when I asked if they needed help opening their milks. No clout whatsoever. Absolute anonymous vibes.

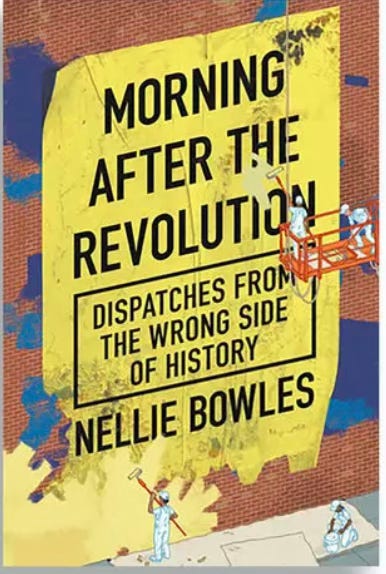

Bowles, meanwhile, has spent an entire career writing to an audience many times larger than mine— first at the San Francisco Chronicle, then the New York Times and more recently at The Free Press. She is, like all of us, concerned about other people’s opinions, but I suspect mostly if those people have fancier bylines and larger social media followings than myself. It’s that specific group’s knee jerk progressivism and intolerance to “heterodox” thinkers that serves as Morning After’s origin story. You see, Bowles once toed the elite liberal media party line (she cites such bonafides as supporting universal healthcare, attending a Verso Books/The Nation party and drinking an I’m-with-her-icane the evening of the 2016 election), but that was before the book’s titular “revolution.” After the summer of 2020, Bowles began reporting on woke excesses like the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone in Seattle and the speaking order at Democratic Socialists of America conferences. She fell in love with a self-proclaimed apostate, the Times writer turned Free Press founder Bari Weiss. Her old friends grew more annoyed with her new opinions, so she, in turn, grew less generous towards theirs.

Morning After is a frequently mean-spirited and snarky book. Its appeal is in Bowles’ identity as a turncoat, a former member of the woke mob who broke free. Conservatives in particular love these kind of stories, ones that reinforce tired truisms about how leftism is the domain of the young and naive. Not surprisingly, it’s being praised by the kind of outlets that love sticking it to the wokesters and pilloried by those that Bowles criticizes as borderline Maoist rags. It’s a familiar cycle by this point: cultural criticism as an exercise in flattering one’s preexisting opinions.

I wanted to read The Morning After, though, not because I felt a need to jump into a circular firing squad composed primarily of Columbia Journalism School graduates with varying takes on pronouns, but because I am legitimately invested in the book’s ostensible topic. I too wrote a book that wrestles with the limits of leftist self-righteousness, in particular how I tried (unsuccessfully) to cleanse my racial guilt through the studied cultivation of pristine political opinions. And though I assumed that there’d be plenty in Morning After with which I’d take umbrage, I found an excerpt Bowles published last week— about how she regrets jumping on social media cancellation bandwagons in order to maintain her own cool girl capital with other big name writers— to be vulnerable and reflective.

And so, yesterday I sat down at the kind of coffee shop whose denizens Bowles would likely mock for their hair colors and openness to reparations. I read The Morning After in a single sitting. I was promised laughter and lightheartedness. The book was marketed as a collection of acerbic commentaries on leftist excess in the tradition of Wolfe or Didion (for the record, neither is the funniest writer on my shelf, but I get why an essayist seeking to really jab the New Yorker tote bag set would evoke their names). And it was, for the record, a breezy read. There are some legitimately fun, well-crafted sentences in there. It’s easy to ride shotgun as Bowles jots down strident protest chants or logs onto an anti-racism Zoom, soaking in the shear tonnage of digital earnestness. But it didn’t leave me cackling, nor did it offend my knee-jerk leftist sensibilities. It mostly just made me sad. Like empty-feeling-in-my stomach, jeez-is-this-who-we-are-to-each-other sad.

You want to know what really got me? Remember that cancellation essay? The one that earnestly considered the human cost to a politics of in-group signaling and performative cruelty? That appears at the end of the book, after Bowles has spent pages upon pages being, well, performatively cruel to people with whom she disagrees politically. She doesn’t technically engage in a cancellation, if only because the only people she criticizes by name have long been anti-woke punching bags (former San Francisco prosecutor Chesa Boudin, Black Lives Matter founder-turned-millionaire Patrisse Khan-Cullors, “Characteristics of White Supremacy” author Tema Okun), but there’s a clear pattern as to which characters, over the course of the book, are offered a sympathetic read and which ones merely appear as barely-two-dimensional, origami paper villains.

In a particularly illustrative excerpt, Bowles recounts a high-profile homeless encampment in her gentrified Los Angeles neighborhood. Never mind the fact that the majority of houses in Echo Park now sell in the millions. In Bowles’ retelling, the encampment’s opponents were all salt-of-the-Earth Latino families, whereas everybody who supported it were wealthy White anarchist tourists (she is very concerned that one of the activists owns an expensive car and has rich parents). As is so often the case in these discussions, the homeless themselves are barely granted personhood— they appear in the narrative as a vague miasma of fentanyl and vice. Bowles never interviews any of the tent dwellers, but makes sure to note that when their camp was eventually raided, police found “untold” numbers of machetes (coincidentally, if the police were to raid my house, they would also find an “untold” number of machetes, mostly because we aren’t a society that rigorously documents our machete inventory).

Ugh. It’s hard to write about this without resorting to the same easy dunks that the book itself traffics in, so let’s back up. Again, when I finished the book, my first thought wasn’t how eager I was to write a blistering take-down of Morning After’s “wrongthink” in order to curry favor with my leftist readers. I really was thoroughly bummed out. Let’s stick with that feeling.

There are, sprinkled throughout the pages of this book, occasional nods at empathy and social concern. But that’s what makes its drive-by cruelty particularly depressing. It’s actually not too hard to simultaneously believe that leftists can be judgmental and group-thinky without being coldly dismissive of trans youth or people living on the streets of San Francisco. Why is Bowles, who earnestly believes that her journalistic curiosity was stifled at The Times when she wouldn’t hew to her colleagues’ liberal beliefs, now so incurious about any of her new books’ progressive subjects? Why does she spend more time, for instance, judging the relative slickness of Minneapolis police abolitionists’ websites than actually talking to them? Why must the pursuit of an ethical life be less about building communities of care than a mere self-conscious hurdle from one insular, gossipy political clubhouse to another?

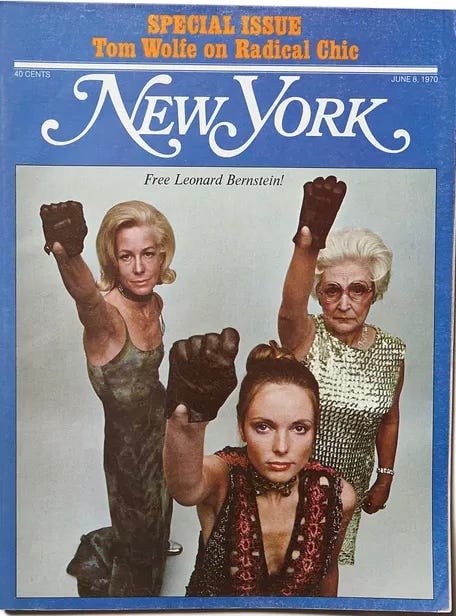

The two specific Didion and Wolfe essays that are often cited in the same breath is the former’s “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” and the latter’s “Radical Chic.” They’re both counterculture critiques, I suppose, but their emotional undercurrent is actually quite different. “Slouching,” a product of Didion’s short-term residency with the hippies of Haight-Ashbury, is elegiac and heartbroken. The author doesn’t merely mock the longhairs; she mourns a country where kids run away from home, searching for community but mostly finding drugs, trying to re-create adulthood from scratch without the tools or vocabulary to do so. Her characters, a collection of literal lost boys and girls, aren’t heroic, but they are full human beings. In contrast, Wolfe’s sneering profile of a Black Panther fundraiser at Leonard and Felicia Bernstein’s lavish Manhattan penthouse is merely a well-written exercise in shooting fish in barrels. Did you hear the one about the out-of-touch rich person trying to buy revolutionary credibility? I hear Roquefort was involved, the least Maoist of all cheeses. What idiots. Well, back to turning a blind eye to the rise of Ronald Reagan.

That’s all to say, I was crossing my fingers that Bowles’ latest would feature more of the former’s empathy and less of the latter’s now-hack recitation of privileged hypocrisies and cringey political silliness. Perhaps that was a naive expectation. After all, Bowles’ bills are currently paid for by an audience with a seemingly unquenchable appetite for jokes about land acknowledgments and “brave” exposes about how some Brooklyn elementary teachers have leftist political opinions. But I do trust Bowles when she writes about her inherent curiosity. So too do I trust the moments in the book where she’s vulnerable, when she questions, if only for a second, the story she already decided to tell before she arrived on the scene. And so, if what I wished for, when I started this book, was a more curious interlocutor, I’d be a hypocrite if I didn’t offer a bit of that in turn.

Again, I’m just a dad in Milwaukee. Notably, I’m not a book critic. In my professional and personal life, though, I’ve found that questions are often more useful than opinions. So if I were the kind of person whose social cache mattered to Nellie Bowles, here’s what I’d ask her. There are no gotchas here, no leading questions, and no false sanctimony. What do we have to give each other, after all, if not our curiosity and our honest hearts?

Hi Nellie,

I hope that your publication day was a joy. When my (first? only?) book came out a couple months ago, I made the mistake of working so hard to calibrate my own emotions that I forgot to celebrate. I hope you were smarter than me.

I breezed through your book quickly, which I hope you take as a compliment. There are roughly a hundred books on my shelf that pander much more to my prior convictions that I haven’t finished. Not surprisingly, your debut was definitely not written for me. I disagreed with far more of your arguments than I agreed. You’ve been around this discursive block before, though, so I’m sure you can anticipate my concerns. I bet you have more than a few counterpoints.

Instead of those arguments, though, I thought I’d share a few questions I had after finishing your book. They’re about you and your experience of the past few years. I’m not leading to anything here, and I’m definitely not trying to change your mind. Whether I loved your book or not, you gave a gift of yourself by writing it. This seemed like the least I could do in return.

Here’s what I wonder…

You don’t dwell on the emotions you felt when you quit the New York Times and left behind many of those friendships, but you do mention that it was (a). your dream job and that you (b). legitimately loved the years when you felt embraced by that community. How did leaving (and feeling abandoned by) that group feel? Especially since it sounds like so many of your old friends really judged (and still judge) your wife? I know that the lesson you took from that departure was that your old community was in the wrong, but are there any doubts there? Do you long for reconciliation, or just the ability to move on?

There are a couple moments throughout the book when you admit to actually getting something from a “progressive” experience that you expected to hate. The first was when you were legitimately moved to tears in a somatic anti-racism course. The second was when your family attended a drag queen tot shabbat at your synagogue and found it… surprisingly theologically deep. What was it about those two political experiences that felt differently from so many of the other experiences you recount in the book? Are there any lessons there, for people trying to build and sustain political movements?

This question is more critical and pointed, but it comes from a curious place. I notice that, even when you considered yourself more progressive, so much of your politics was either about (a). supporting movements that directly benefited you (for instance, the fight for gay marriage) or (b). parroting the same beliefs as your peer group. It does seem like many of the movements you judge the most (such as efforts to defund or abolish the police, gain broader acceptance for the trans community, or treat homeless people with dignity) would require more of a lifestyle or behavior change on your part. Does that strike you as accurate? What about those movements, and the changes that they’re requesting of society (and of you personally) scare you? What do you notice about the boundaries between your intellectual critiques and those fears? Do they feel fixed or fuzzy?

I notice that throughout the book, you’re particularly judgmental of White activists from rich families. You’re quick to point out whenever an activist holds one or both of those identity markers, often to discredit them. You personally are both White and come from a very wealthy family, a fact that often gets pointed out (in pretty snarky ways) by your critics. Do you feel guilty about those identities? Have they caused you any cognitive dissonance as you’ve attempted to live an ethical life in an unequal society? If so, what has wrestling with that looked like over time?

You’re a mom! I love that for you. I know that being a dad has very much changed how I view so many things— my relationship to ambition, my own predilection towards self-righteousness and trying to win arguments, the reasons I even engage with politics, the rawness of my fears for the world, my understanding of my own privilege, my overall level of fatigue, etc. I know it’s hard to talk about how parenthood impacts our politics without settling into easy cliches, but what has that looked like for you?

What is your dream for this book? Are you hoping it inspires reflection on the left or that it emboldens moderates and conservatives to defeat me and my fellow leftists? In either case, towards what end? Again, I’ll admit, I’m worried that a book like this hardens and calcifies our political discourse in a way that’s unhelpful. I mean this earnestly, though: I trust that’s not why you wrote it. There’s an aspiration here. What is it?

Maybe this is the same question, but what am I misunderstanding about your book? As I’ve made it clear, it depressed me, in that it seemed to give its readers permission to care less and to be less curious about those activists who are challenging the current unequal status quo. Is that a misreading? If so, why?

Again, thanks for your work. It made me more curious. And though you and I currently disagree on many things, I can tell that we both at least aspire to be acolytes in the church of curiosity. It’s a beautiful religion, isn’t it? At least for me, it’s a hard one to stay devoted to regularly. I experienced that challenge as I read your book. Heck, I experienced that challenge as I tried writing about your book. That’s the trick, isn’t it. Not being curious, but staying curious.

I hope you’re well. For real.

-Garrett

End notes:

Speaking of books about White leftist self-righteousness, I would still very much like you to buy mine (and also do other things to help it- review it, share it with your friends, recommend it for your workplace DEI group that we won’t tell the Free Press about, etc.). Also, my lovably ramshackle (but oh so fun) book tour/excuse to do rad things with rad people keeps trucking along! COME HANG OUT, FRIENDS:

Next Thursday, May 23rd, in Minneapolis. Look at this line-up of co-sponsors: Southwest Alliance for Equity! Friends for a Nonviolent World! The Minneapolis Friends Meeting! Comma Books! You all, it’s gonna be a cozy good time. 7:30 PM at the Friends Meetinghouse (4401 York Ave. S.). RSVP here!

The following Thursday, May 30th, I’m in New York for the Literary Swag book club. That’s a membership group (but a great one). I am honestly not sure if there’s still a chance to join for this month, but maybe it doesn't hurt to ask? In the meantime, is there anything fun to do in New York? I don’t know much about it! The Windy City, they call it!

June 4th, I’m in the Literal Redwoods (well, not the city of Redwoods, I mean the town with the redwood trees)! Mill Valley, CA at the Mill Valley Public Library! 6:30 PM! Shout out to Sausalito Books by the Bay and Madrona Bakery for being co-sponsors here!

June 5th, 7:00 PM, I’m in Oakland and we’re gonna do a “Garrett Bucks and Friends” (which friends? stay tuned!) workshop/hang-out/book talk/good vibes time. Where? Temescal Commons, 480 42nd Street. You all, it’s gonna be so rad.

Residents of Washington State! Or people who care about residents of Washington State! Did you know that there is a grassroots campaign to get y’all actual universal healthcare? It’s true. It’s called WHOLE WASHINGTON and I’m leading a public, virtual organizing training for them on June 19TH at 6:00 PM PT. RSVP here.

Do you enjoy the White Pages? Thanks! Would you like it to continue? Me too! Could you consider a paid subscription? Not too pricey, actually! For the money I spent on an e-copy of Morning After The Revolution, I could have subscribed for three months! Math!

SONG OF THE WEEK! Last week, FX (a TV network, apparently) released a teaser trailer for Season Three of The Bear. If you’ve been around here for a while, you likely remember that few pieces of art made my heart grow more expansive than the last season. And my favorite scene? The one in the penultimate episode, the really heartwarming one. I won’t give it away, but I will tell you that it was soundtracked by this number, a cover of what I’ve since learned is the song most likely to make Australians hug each other in a bar.

I love this so much. Haven’t read the book, but I really appreciate the discipline you brought to this—emotionally, literarily, and otherwise. What a great model for all of us.

I really loved this piece and how you modeled curiosity while maintaining a clear commitment to your values. So much we can learn from this!