Photo credits here.

The 2010s began like all hell unleashed.

There was an earthquake in Haiti. One of the worst imaginable. Do you remember it?

I don’t. I mean, not really…

Without looking it up, I couldn’t have told you the quake’s magnitude, nor the exact year it took place, nor the death toll, nor the number of mass graves necessitated by that death toll.

It was over 220,000, by the way. At least 220,000 people died. That’s a hell of a number to forget.

I had also forgotten how we reacted back in the U.S. There were the particularly surreal displays of Ugly Americanism (apparently a church in Idaho went down and straight up kidnapped a few dozen children). There were good attempts by smart people to draw connections between the acute disaster of tectonic plates and the slow bleed of colonialism/imperialism/International Anti-Blackness. There were the clumsy displays of sympathy (Our celebrities recorded one of those overstuffed charity singles. This one featured Vin Diesel and T-Pain and Celine Dion. Katy Perry was not invited even though she released a perfect pop song that year. Its chorus proclaimed “Don’t ever look back; don’t ever look back,” a more direct and less treacly message in the face of tragedy than “We Are The World 25 For Haiti”).

And then there was the moment when we turned away. There is always that moment. In this case, we did so with the anesthetizing knowledge that a familiar face (Bill Clinton, in his role as UN Special Envoy) would ensure that everything-that-should-be-done-at-moments-like-this would be done.

We were wrong about that, as it turns out. The Clinton-led aid effort was a mess. American corporations were privileged over Haitians. Unhelpful stuff was built poorly and expensively. Democracy was thwarted. Pras from the Fugees was more heavily involved than you’d assume he’d be.

We may have seen all of that coming if we’d had more pre-earthquake experience listening to actual Haitians (and not just the small collection of elites— the Sweet Mickeys and Banana Men— who attain power thanks to back rooms full of elite Americans). If we had done so, we’d have known, for instance, that this wasn’t even Clinton’s first rodeo mucking things up down there.

You may have heard that, as this decade comes to a close, Haitians have taken to the streets to protest their government again. These things are not unrelated.

There are moments when we pay attention. There are moments when we turn away.

Here are some other things that happened ten years ago.

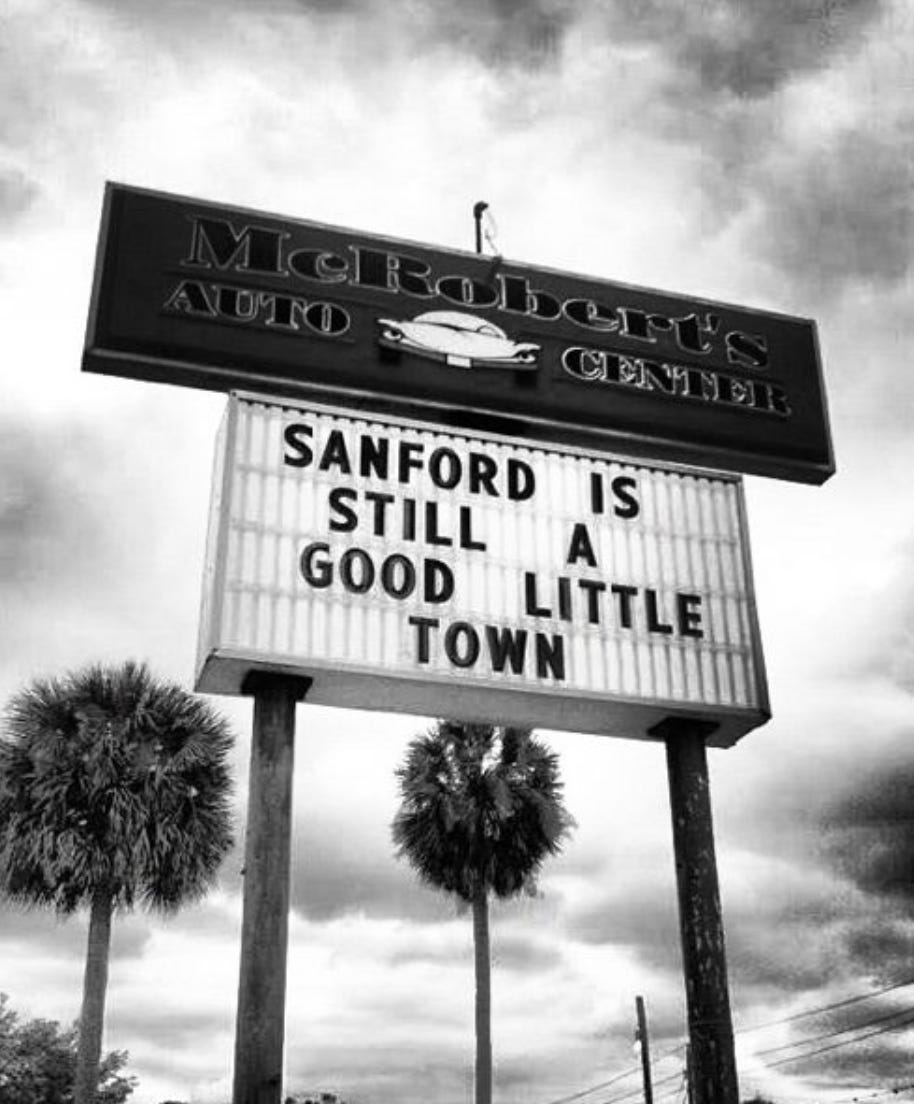

In 2010, I had never heard of Sanford, Florida. But temperatures were rising in that town’s Retreat at Twin Lakes housing development. Fears abounded about imminent threats to their specific version of the American dream (a gated community with easy access to the Seminole Towne Center Mall, home to both a Yankee Candle and a Piercing Pagoda). The housing bubble had burst— nowhere more explosively than in sun-choked subdivisions like theirs. Home prices had plummeted. Condos were converted to rentals. What had been an exclusive enclave was seeing an influx of new residents, families drawn in by its newfound affordability.

What I’m saying is that the neighborhood was getting poorer and Blacker.

Throughout 2010, more and more “concerned neighbors” started talking to each other about crime. By 2011, after a break-in at Olivia Bertalan’s place, over 30 of those neighbors organized a formal community watch. A serial police-tipster named George Zimmerman eagerly volunteered as captain. It seemed like a good idea to all involved.

Two years later, Trayvon Martin likely hadn’t been told any of this back-story. He was just visiting town for a while with his dad. He was just out on a snack run.

Nobody paid attention until, all of a sudden, we all paid attention.

Back in 2010, I had never heard of Jennings, MO, either. Tensions were high there, too. Jennings is a mostly Black community in North County St. Louis. The source of their insecurity was a demonstrably racist, corrupt police department with a major use-of-force problem. At the turn of the decade, the cops there were so notorious that Black elected officials from neighboring communities actively avoided driving across town lines. In January 2011, a white officer pursued a Black woman miles out of city limits, shooting at her as he drove. Her crime was riding in a car with expired plates. There was a child in the back seat.

Two months later, the Jennings City Council decided a clean slate was needed. The entire force was disbanded; all officers lost their jobs.

The first two years of the new decade were comparatively quieter in nearby, predominately white, St. Charles, MO. Parents were happy with their schools. A new facilities project was coming along nicely. The Francis Howell High Vikings were beginning what would be a half decade of dominance, including a state title game appearance.

By 2013, however, all was not calm. Due to a Missouri law that allowed students at unaccredited school districts to transfer to neighboring schools, Francis Howell was poised for change. Nearly 1000 mostly Black students from the perennially low performing Normandy School District (which served a number of North County municipalities) were on their way. As Nikole-Hannah Jones reported for both ProPublica and This American Life, the response from the good people of St. Charles was monumentally ugly. I’d only recommend reading transcripts of the district’s public forums if you’re a fan of frightened parents spinning fever dreams about drug-dealing, functionally illiterate interlopers puncturing their Viking valhalla.

Long story short, those parents lost the battle but they won the war. Thanks to some rhetorical trickery, Normandy Schools reopened under a new name, undoing the law. The transfer program was scrapped after only a year. The final decision was handed down in the summer of 2014, just before classes began.

Other things happened that August, too.

Remember the Jennings police department? Well, one thing that happens when a town fires all of its cops is that they find new jobs elsewhere.

This is the case even if they were fired for posing a collective threat to the Black residents whom they were supposed to be serving.

And so it goes that shortly after he lost his job in Jennings, a cop named Darren Wilson found a [reportedly] better paying one in a bigger department down the road.

Wilson was allowed to move across city lines with impunity. The same wasn’t true for kids at Normandy High, including kids who lived around Wilson’s new beat in Ferguson. Every last one of those kids got the message, by the summer of 2014, that they were to be kept in their place— that the world outside of their small corner of North County was not for them.

It’s impossible to say if Michael Brown Jr. personally internalized that message of rejection. To be fair, he wasn’t one of the 1000 students that had tried to transfer out. He graduated from Normandy High.

What is undeniable is that, come August, Darren Wilson had a new job and a new gun in his hand. Michael Brown Jr. was dead in front of the Canfield Green apartments. In response, many of those same students whose mere existence had triggered protests from white parents a year prior, now finally let their rage and sorrow out onto the streets.

Nobody paid attention until, all of a sudden, we all paid attention.

I’m well aware that these newsletters don’t focus much on praise-worthy justice work. That’s to my discredit.

I truly hope that the past ten years will be remembered for all the ways activists challenged us, particularly those of us who sit at the top of pyramids of power. This was the decade when communities whose basic pleas had been ignored for generations found new ways to break through. That’s true for Black activists pushing for the right to live, Muslim activists pleading for recognition of their humanity, Latinx activists crying out for the right to keep families together and Indigenous activists rising up in the name of true sovereignty. The same pattern has played out in parallel justice spaces. It is wild that we needed a movement for men to be held marginally accountable for sexual violence or one to push non-teenagers to admit that the world is on fire. It may be small, teetering progress, but the activists who got us this far deserve tremendous credit.

But still, we are so far from where we need to be, especially those of us who get a choice as to when we turn away. Collectively, we likely did a better job of training our gaze on our collective failures than in years past. And yet, it seems as if we only ever offered our full attention when there was a Black body lying in the street.

In the 2010s, showing up for racial justice all too often meant arriving on the scene too late to be truly useful.

Long before Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown Jr. ceased to be boys and were reborn as signifiers, long before 200,000 Haitians became anonymous statistics, there were unnoticed, anodyne rooms full of white people. Board rooms. Police and fire commission meetings. Condominium rec rooms. PTA meetings. USAID conferences.

In the next decade, there will be many more of those rooms. If you’re white, you will invariably be in many of them. And there will be very little for you to personally gain from approaching those rooms with the same urgency that we do in moments of acute tragedy. You will not be applauded. You will receive no salve for your guilt.

But what could be true if you organized those rooms as if all of our lives depended on it?

What if…

What if first five and then ten and then twenty five neighbors in Sanford had said “I don’t like what our fear is doing to us… we’re better than this.” ? What if first twenty and then fifty and then one hundred St. Charles parents had said “We’re on the wrong side of history here…how do we welcome our kids’ new classmates?” What if first one and then two white members of the Ferguson City Council had urged caution before hiring cops who had just been fired for racism? What if white Ferguson residents had demanded that the Jennings story be a cautionary tale to examine their own department’s practices? And what if they had all done so because they had listened to Black friends, colleagues and neighbors who weren’t in those rooms?

What if a million Americans had demanded reparations and self-determination for Haiti, not conditional aid and self-dealing? What if that act of solidarity across national borders was easier and more natural because we already had practice showing solidarity to our neighbors across the street?

And finally, what if showing up in the rooms closest to home expanded our imagination as to how to pressure those that are closed to all but a select few— the bank headquarters where mass foreclosures were first triggered, the federal government that bled municipal coffers dry and left them to nickel and dime their own citizens, the state governments that do everything they can to stack the deck towards the St. Charles’ of the world and away from places like Jennings/Ferguson/Normandy?

I’m not proposing a fantasy in which different actions in any of these rooms would have averted past tragedies. All I know is that we didn’t try. The spaces we assumed were benign were actually the spaces that mattered the most.

The past decade was one, for white people, of situational shocks, of charity singles, of doing what was necessary in the moment of tragedy to stop feeling the bad feelings and return, as quickly as possible, to a blanket of comfort.

In the next decade, I don’t want us to become more effective mourners. I dream of fewer tragedies to be mourned. And while I have no doubt that it will be Black and Brown and Indigenous people leading us there, we will need the voices and organizing muscles of white people in the millions of rooms where polite malevolence takes root without a passing glance.

If we are to imagine a better world, it starts in the spaces we’ve ignored— the rooms about which we’ve had no liberatory imagination whatsoever.

There is a beach under the paving stones, but we have to dig to find it.

Thank you for reading this year. Here’s to a new decade and a million opportunities to be better neighbors.

Don’t ever look back; don’t ever look back.