We are so small. The problems we face are so enormous.

And so we pick up a shovel and start digging...

“Maybe when you are 20 years old you can believe [that all you need is] revolution, socialism and even the resurrection of the flesh. But have no illusions; the struggle is permanent. I have fought for fifty years and I will continue fighting until I die. That is all I know how to do. And I hope you will join me.”

-Maria da Conceicao Tavares

I read a New York Times article yesterday. It was about the clinical tests for a new Covid-19 treatment called remdesivir (It’s from a company called Gilead! What could go wrong?). I know nothing about the tests or the drug or… you know… science, so the article was lost on me. All I know is that I was reading it and then I saw the line “outcomes were scored on a scale of recovery to death” which is one hell of a continuum.

There’s something about the aggressive banality of that line. It’s just sitting there, pointing out tragedy but not mourning it. I guess our entire lives are antiseptic right now. Why shouldn’t our prose be as well?

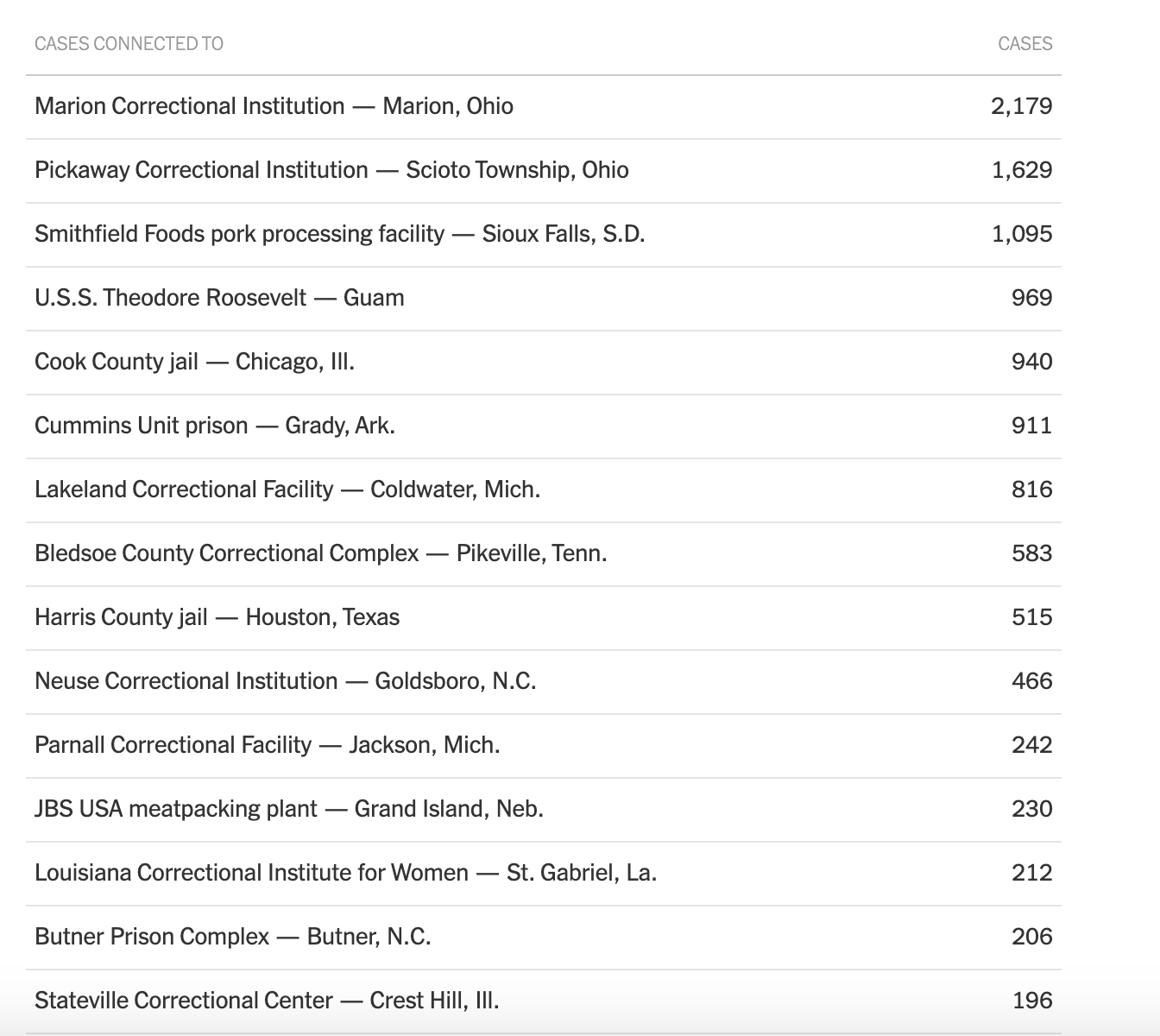

I wasn’t on the Times website to read about clinical trials. I had gotten distracted, which happens a bunch these days. I was there to look at cluster tables, the list of the largest Covid-19 hot spots. God if there isn’t a more honest accounting of the extent to which we are or aren’t a free and democratic country.

Have you looked at these tables?

Here’s the full NYTimes story from which this screenshot was snagged.

Prison. Prison. Meatpacking plant. Warship. Prison. Prison. Prison. Prison. Prison. Prison. Meatpacking plant. Prison. The list goes on. As you get deeper down, the ratio of prisons to meatpacking plants evens out. They don’t count The Navajo Nation as a cluster but if you were to look at county-wide data, Mckinley County, NM is right there as well. Goodness we aren’t even subtle as to the communities we deem to be expendable.

You already know this. I’m not the first to throw their hands up and say “THIS PANDEMIC IS NOT IMPACTING US ALL EQUITABLY.” You probably heard that the Governor of Iowa, home of many of the worst meatpacking outbreaks, is going to deny unemployment benefits to anybody who refuses to go to work because of Covid-19. Man if that’s not a choice. You can die of hunger or you can die of Coronavirus, as long as agribusiness shareholder return is maximized, as long as the rest of us don’t have to bear the indignity of pork chop shortages at Hy-Vee.

Outcomes are scored on a continuum of recovery or death. Pre-scored, as it turns out.

Here’s a story about me as a teenager. It takes place between 1997-1999, back in our country’s Golden Summers of Power Ballad Movie Soundtracks. [An aside: I’m sure that kids these days suffer great indignities (for example: pandemics). But is there truly anything sadder than having your high school summer pop radio playlists filled not with undeniable beach bops and bonfire jams but instead overstuffed Aerosmith dirges about how much you miss your roughneck oil derrick boyfriend while he and his buddies are up in space drilling holes into civilization-destroying asteroids?]

Early in high school, I fell in with a chill, progressive Methodist youth group. This in turn led to a sprawling network of teen church stuff, first across Montana and then nationwide. It was all quite great, and I soon decided that I wanted to be a Methodist preacher when I grew up. What I didn’t know at the time was that, just as I was coming of age in Methodism, mainstream Protestantism in general was facing an existential crisis of aging parishioners and emptying pews. This meant that if you were a young person who not only felt drawn to the church but actually wanted to work for it, like as their job, you suddenly had access to an absolute truckload of free trips and conferences and institutes.

And so, thanks what seemed at the time like a never-ending spigot of Lilly Endowment money, I spent high school summers in Nashville and Knoxville and Atlanta. Oh God it was perfect, every part of it. It was the novelty of humidity and traffic and a world completely unlike Montana. It was the high of pre-college faux-independence, of eating dorm food and doing your own laundry while somebody’s CD radio played “Closing Time.” It was the rush of being surrounded by like-minded weirdos who seemed simultaneously cooler than you but just as afflicted with the same decidedly-uncool quirk. It was the always intoxicating teenage hack (the same one utilized by every high school’s resident cool English teacher) of having grownups treat you like you were capable of critical thought, of wrestling with big ideas.

The summer I spent in Atlanta in ‘98 was particularly mind-blowing, in spite of an absolute horror show of summer soundtrack releases (Godzilla, City of Angels, Armageddon AND Rush Hour… just writing that list makes you want to bleed just to know you’re alive). I was at Emory, at the Youth Theology Institute, where our cohort of teenage weirdos got to wrestle with queer theory and Black nationalism and womanist theology and theodicy and questions about our role in the world. It was exciting and heady and it changed my life.

And yet— we were still teenagers. So as much as we loved feeling smart and important, we still spent 80% of our mental energy distracted by the same questions we had before we arrived (namely: is there anybody in my immediate vicinity who would be willing to make out with me?). Oh God I developed some epic crushes throughout those summers, almost all of them unrequited. There was one in particular, borne in that summer in Atlanta, that I carried on long past any reasonable sell-by date. It wasn’t until my crush was fully snuffed out during an unceremonious reunion a couple summers later (at yet another summer theology conference— again, it was a VERY generous spigot) that I realized what had really been going on there.

Teenage emotions are always self-important (see also: Creek, Dawson’s, yet another gift from my generation to yours), but there was something to the particular snow globe of hormones and self-centeredness and intellectual headiness and theology that, when shaken up all together, made for one heck of a mental blizzard. It was the perfect space to convince yourself that you were at the center of a grand and glorious narrative. If you were to find love in the midst of all this talk of God and liberatory politics, well, that meant that it was really meant to be. And if that aspect of your life was pre-ordained, that meant that you had proof as to a far greater assurance of order and certainty in the world. And so when I sat on another sticky Southern college bench two years later and heard, essentially “Garrett, you’re a good friend but I’ve never had any feelings for you and if you’re honest with yourself you already knew that” it felt devastating in the way iconic teenage heartbreak always does but it then revealed itself as an invitation. I had to begin the work of constructing my life not based on the comfort of a pre-determined cosmic story, but on my best guesses as to what was good and kind and right.

That’s the story of growing up, of course. And though mine involved theology and modern rock radio and my first taste of grits, I’m sure you have your own. It’s easy to misunderstand it as a story about relative levels of faith but that misses the point. These are moments that are shared equally by the atheist and the unattached seeker and the true believer. It’s about the times in our life when we learn that we aren’t personally at the center of history but that we should do our best to be kind and good and loving regardless.

Do any of us know how to answer when somebody asks us how we’re doing these days? Hand to God, I try to be honest and evocative and not just fumble my way through a half-hearted farce of an answer. The problem is, I can’t get half the words out before I’m questioning my own reliability as a narrator. “Am I really just fine? Is that thing I just named as being the stressful thing actually the stressful thing? Do I even know how I’m doing?”

It’s just complicated, you know? Truth be told, there is so much more joy in my immediate world. It’s there in the way my life has suddenly collapsed into my kids and our daily routine and the wild turkeys we see by the river and my wife and the triumphs and defeats she wears on her face as she gets home from the clinic and the giardiniera I’ve been putting on everything I eat even though it’s way too spicy and it makes me cough and the very cold Miller Lite tallboy I drink in the shower after a late night run.

And yet.

It’s hard to say how I’m doing because the joys are so immediate, so specific. And there, right outside the gate, are the frightening things and the rage-inducing things and the narrative destroying things. And those are all so damn big. And so non-specific. Just vague and pulsating and ill-defined.

It’s that power imbalance that makes it so that I don’t know what direction is up. Am I doing well because I am healthy and my immediate world is full of things for which I’m grateful or am I doing quite badly because the world is out of control in ways that are both old and new at once and there is a continuum of recovery and death and I am so powerless in the midst of it all?

This is an email newsletter written disproportionally to an audience of do-gooder white people, a cohort that has been told that they should stop acting like saviors, stop placing themselves dead center stage for the Broadway opening of How We Stopped Racism. We know this is the wrong answer, but we rarely talk, us clumsy racism-dislikers, about why we fall into the trap.

Don’t get me wrong. I know damn well that a huge chunk of it is ego and validation chasing. If I didn’t cop to that right away, goodness knows a small army of friends and former colleagues would point out plenty of Lookin’ For Love In All The Wrong Places missteps from my own backstory. But I can’t shake the feeling that isn’t all there is to it. Yes, we want to be heroes, but we also deeply crave the assurance that there is a broader story here. It’s that cited-to-death King line about “moral arcs of the universe” mixed with the Didion line about “the sermon in the suicide… the social and moral lesson in the murder of five.” We tell ourselves stories not just in order to live, it turns out, but to assure ourselves that the shame we feel now might someday be erased. We crave the same narrative certainty as a teenager searching not merely for romance, but for validation that their desired romantic pairing is The One True Path.

And so we come to moments such as this one, face to face with the twin truths of randomness (this virus!) and predictability (the infection clusters!). And when those of us who are more likely to be spared from tragedy are honest with ourselves, we realize that there IS a bigger story at play, just not the one for which we were hoping. It is a story that offers plenty of opportunities for action, but no myth of heroism. It is as if we are all living on a mountain, some of us on top, some down below. And though you can’t predict when the mountain will shake and trigger an avalanche, every time it does so it almost disproportionally wallops the folks on the bottom. Everybody knows that if the mountain were to be leveled the snowfall that created the avalanches could be experienced more benignly.

And yet, in between catastrophes, the situation on the mountain remains unchanged.

I’ve been reading Catherine Fosl’s biography about Anne Braden recently. There are few white people in history who did more for the cause of anti-racism than Anne Braden (she is one of only six white people highlighted positively in Letter from the Birmingham Jail). What’s striking about her biography, though, is that for her entire activist life, Braden never tried to place herself at the center of a virtuous story. Her path is one foot in front of the other, small logical steps leading to larger ones. As she became more outraged about racism, she aligned more daily actions with that concern. She told different stories in her day job as a journalist. She started showing up to meetings that she wouldn’t have gone to previously. She built relationships with Black activists to the point that they trusted her enough to ask her to do more. When a Black couple called on her and her husband to put their name on the deed to a house they were restricted from purchasing, she did it. When that led to a sedition charge, she did her damndest to put the whole system on trial. When she realized the numbers were against her she organized other white people who didn’t share her conviction. She did the only thing one can when you wake up and discover that you’re on top of an avalanche mountain. She took note of her location and started digging, leveling as much of her little Louisville-based outpost as she could.

Oh goodness this is such a destabilizing moment. We are all so tiny. There is no meta-narrative capable of making us feel bigger. There is no single right action that gets us out. But if ever there was a moment to accept the invitation to stop searching for salvation and instead get quietly, persistently and humbly back to work, it’s now. This mountain is only tilted in this direction because millions of us have shown an unwillingness to start digging our section of it down. The question isn’t whether there is a guaranteed path out of this mess— it’s where you’re standing, who’s standing next to you and what it would look like for first the nearest two of you, then the nearest twenty of you and then the nearest two hundred of you to pick up shovels together.

End Notes:

I am resisting offering a stale, canned list of suggested actions. I truly believe doing so misses the point. Those lists aren’t rooted in your corner of the world, your chunk of the mountain. If you are a white person and honestly don’t know where to start, though, I’m always happy to talk, help connect you in your community and offer suggestions and encouragement. Just reply to this email or send me a DM on any social platform (and for those who’ve replied to a previous offering- watch your inbox, I promise. My work day in this weird moment is from 9:00 PM to 2:00 AM but I’m getting to it and I haven’t forgotten you).

Apologies to my staunchly Montanan mother, for the grave apostasy of proposing (even metaphorically) that a mountain be leveled. I promise I will never do it again.

Shout out to all my MULTIPLE unrequited former crushes who subscribe to this newsletter. We made it, fam.

Image credits here

Song credits: (1). “Flagpole Sitta” by Harvey Danger because the summer of 1998 will live in our hearts forever. (2). “Teenage Kicks” by the Undertones because we all need excitement and we need it fast.