We had to pretend that the stolen mountain was a shrine to our greatness because it was easier than sitting with our angst

On visiting an iconic American site for the first time

Top notes:

I am back from two weeks back home in Montana (and elsewhere in the West, as will be discussed shortly). Thanks for your patience with some modifications to business as usual while I was out of town (varying publication schedules, looser essays, etc.). I’ll be picking up the summer movie series next week. In the meantime, summer can be a slow time for support around these parts, so if you enjoy or value what you read here, please consider sharing it and/or pitching in with a paid subscription. Thanks a million for considering (and I hope you’ll appreciate some of the perks— the online community, bonus essays and even fun stickers and/or merch— as tokens of my sincere gratitude).

I went to Mount Rushmore this past weekend. I had never been there before. Though I grew up in Montana and my my mom and dad are from South Dakota, my family never made the stop on our many long drives across both states. I’m not sure if that was a political boycott on my parents’ part or if it was just the need to make time with six kids in a semi-reliable VW Vanagon. Regardless, we’d always barrel past the self-proclaimed Shrine to Democracy and save our West River rest stop attention for Wall Drug and its free ice water.

There are plenty of good reasons to boycott Mount Rushmore, but you already know that. It— along with the rest of the Black Hills— is the sacred homeland of multiple Lakota nations. In 1868, the United States government signed the Fort Laramie treaty with the Oglala, Miniconjou and Brulé, promising that Pahá Sápa would be Lakota land in perpetuity. That should have settled matters, but White America loves lies both large and small. The Fort Laramie treaty was never going to be worth the paper on which it was written, but it would take a decade and the arrival of a uniquely American main character for its fraudulence to fully reveal itself.

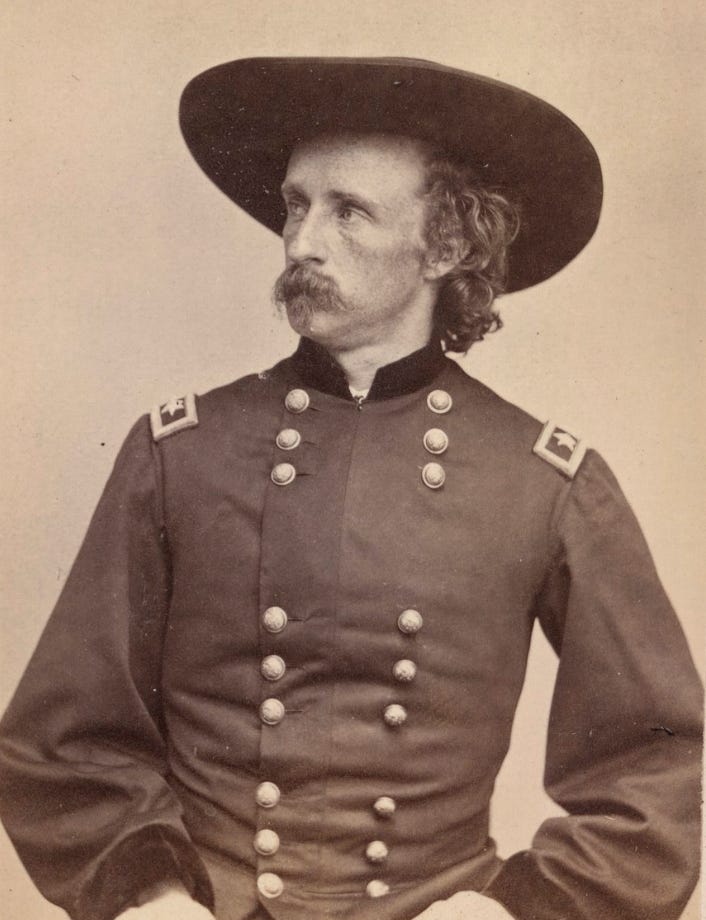

General George Armstrong Custer was a sub-par military leader, but a preternaturally skilled liar. It’s why, even while leading a gold-seeking expedition to the Black Hills, he perfumed his hair with cinnamon and wore a black lace uniform with coils of gold. It’s why he commissioned a photographer to accompany him West in order to produce a steady stream of tough guy glamour shots. And it’s why he triggered a gold rush by sending word back about the riches to be found in the Black Hills even though he had only discovered small traces of placer gold.

Here’s what happens when you trigger a mostly-fraudulent gold rush: White people flood into the Black Hills by the thousands. Technically, this should have been a problem, as it meant that a large chunk of land that the U.S. government had deemed sufficiently undesirable so as to be recognized as Lakota territory suddenly became quite desirable indeed. But come on, did the Lakota really think the United States of America would recognize something as elastic and forgettable as a treaty?

Custer didn’t survive the subsequent wars that his untruths triggered, but ours is a country that rewards its best liars with the prize of immortality. And so— when my family rolled into the area last Thursday— both the campground where we stayed, the nearby town where we bought groceries, and the adjoining state park where we swam and hiked all bore the perfumed general’s name.

I’m not entirely sure why I decided to go to Mount Rushmore. There wasn’t a lot of thought involved. One minute I was considering the sunk moral cost of staying at a campground named for an icon of U.S. settler colonialism, and the next I was googling how far I was from that mountain with the Presidents carved on it. I do remember the pitch I made to my son and nieces to convince them to join me, though. It was something to the effect of “Hey, you know how I write about the stories White America tells itself for a living? It’s sort of interesting that we put a bunch of Presidents on the mountain, right?” I have no idea why that worked. Please don't tell Ron DeSantis, but the real risk of too much critical race theory in the classroom is terrible vacation-adjacent decision making on the part of our young people.

I wasn’t wrong though. Mount Rushmore is interesting, especially when you remember that it has no real reason for existing. There is no United Nations decree that every nation must commemorate a small handful of its former heads-of-state on a remote cliff in one of its least populated states. It’s not like there’s a mound somewhere in Saskatchewan where the Canadian government has erected tributes to its most beloved Prime Ministers (Lester Pearson, Pierre Trudeau and, I don’t know… Tim Horton?).

Mount Rushmore exists not because of any great national necessity, but because Doane Robinson, a one-time employee of the South Dakota Historical Society, thought that carving something monumental in a mountain would attract tourists. He had heard about how the KKK and other Confederate sympathizers had erected their own “White guys on a mountainside” in Georgia, so he called up Gutzon Borglum (the nativist Klanite responsible for Stone Mountain) to repeat the deed. The original idea was for it to be a grand tribute to the cowboy myth, but it didn’t have legs. If only Taylor Sheridan had been alive to manifest that particular destiny, perhaps the West would have been won once and for all. It was Borglum who suggested the whole American exceptionalism angle. He may have loved Rob Lee and Jeff Davis, but he was an equal opportunity hagiographer.

Again, there are a lot of good reasons not to patronize the place.

Do you really want to know why I’ve never visited Mount Rushmore? It’s not because I’ve made a principled stand to boycott all relics of colonialism and anti-Indigenous genocide. Like all self-consciously guilty land acknowledgers, I’ve spent a lifetime conveniently ignoring my hypocrisy on that front. I avoided that particular attraction because I knew that it was built to draw in tourists. I assumed that it would be gauche and tacky. I expected the road up to the site to be choked with airbrushed t-shirt vendors and those shacks where you can dress up as a Wild West outlaw and pose for a pre-yellowed picture. As an insufferable college educated sophisticate, I’ve learned to hide my classism behind thinly veiled judgments of other people’s vacation choices.

The weirdest thing about Mount Rushmore is that it isn’t actually all that gauche or over-the-top. Sure, there’s an ice cream shop, as well as a national park service gift shop where books about democracy share space with an absolutely unhinged selection of personalized mints, but that’s the extent of the crass commercialism. Otherwise, the aesthetic is solemn and self-serious. Upon arrival, you walk down a boulevard lined with state and territorial flags. It’s the stations of the cross, but for patriotic reflection. There is no red white and blue bunting. There’s no Lee Greenwood carrying on about his pride in being an American. It’s just a decently long expanse of monumental grey before the main event: furrowing your brow at chiseled faces in the middle distance.

You have to consciously remind yourself— when you’re staring at the peak that the Lakota call Six Grandfathers Mountain— that there isn’t any good reason for U.S. Presidents to be commemorated here. If the whole site was nothing but Epcot Center Animatronics or Guy Fieri’s Four Score and Seven Beers Ago American Grill, that reminder wouldn’t be necessary. It’s the faux-seriousness that belies the arbitrariness of this happening here. Only one of the four commemorated men spent any time in South Dakota. No monumental victories against tyranny were achieved here. There was once a war nearby, to be clear, but the aggressors in that conflict weren’t vanquished. They won and got to carve their heroes’ faces into a mountain.

I came to Mount Rushmore after two weeks on the road, which is to say that I came to Mount Rushmore after two weeks of interactions with a less intentionally-curated set of conversational partners. I caught up with friends and family members, of course, but I also shot the breeze with campsite neighbors, made small talk with parents at playgrounds and killed time with fellow gas station patrons. I listened to liberals and leftists wrestling with the various existential crises that have become tried and true fixtures of the American summer (cruel Supreme Court decisions overlaid upon a blanket of climate-related dread) and paid conscious attention to my face as conservatives regaled me with their own tales of a world gone to moral hell.

At a bar-b-que the night before the Fourth of July, I asked an old friend how she was doing and she skipped the perfunctory “can’t complain” and instead talked about sleepless nights and creeping nihilism. I blubbered an unsatisfying response before we turned our attention to our daughters giggling and turning cartwheels together. A few nights earlier, at a motel pool in Glendive, MT, a dad from Butte bent my ear not about his own town (a place I love but which is a true casualty of greedy robber barons) but about how unlivable Portland and San Francisco are these days, mostly on account of all the “homeless and the druggies.” It’s gotten so bad that there aren’t any families living there anymore, he informed me, before being drowned out by the crash of his sons cannonballing into the pool.

It is cliché to observe that the only thing Americans can agree on is that Congress is a bunch of crooks and the country is going to hell, but that doesn’t make it any less true. I can’t remember the last time I’ve had a meaningful conversation with anybody from either side of the political spectrum who actually feels optimistic about the current direction of our country. That’s not to draw a moral equivalence between those whose angst stems from naked assaults on human rights vs. those who are angry that drag queens exist and sometimes enjoy reading children’s books. It is notable, though. We’re all filled with dread, but it’s as if we’re afraid that if attempt to make sense of that shared ennui honestly, that somehow the center won’t hold.

It didn’t take long for me to discover that the Dad from Butte and I didn’t share a worldview. I understood why he was fired up, though. He grew up in a town that was literally poisoned by capitalism, but in a country that believed it was naive to imagine any other system working. He was raising his kids in a world that has deemed some human beings expendable enough that we watch them live and die on the streets. He was wrong about a lot of details, but his angst was honest. None of it felt metabolizable. It was all too much. All he could do was rage to a random stranger as both of us tried to keep our kids’ heads above water.

If Mount Rushmore were gaudy, it wouldn’t offer a temporary salve for our collective feeling of betrayal. While it may have been created merely to draw people and money to this corner of South Dakota, that’s no longer its purpose. The monument was packed this past week. The crowd wasn’t overwhelmingly White, nor was it visibly conservative. There were no Thin Blue Lines or entreaties to Make America Great. I wasn’t gifted the easy moral escape hatch of haughty liberal judgement. Instead, I watched as a decent cross section of my country stared at something patently ridiculous (four morally compromised men chiseled into a a stolen mountain) and pretended, at least for a second, that it was sacred and profound.

The experience would have been different without the crowd. The bubble would have burst if we all weren’t on our best behavior, if we weren’t quiet and polite, if we didn’t offer to take each other’s pictures and excitedly shout “oh, that’s a good one!” when handing back one another’s phones. It was as if we had all been suddenly enlisted in a community theater performance— a collective throng whispering in our smiles and “excuse me’s” something to the effect of “We know our country isn’t great, and that it’s never been great. We are smart enough to know that this mountain is stolen and desecrated, but right now it looks grand and silent and we recognize that everybody is tired and has traveled a long way so let’s not admit that we all can see the cracks.”

It was not an environment for grand acts of subversion. Bless my twelve year niece old for recognizing better than I did how the moment deserved to be met. I had just taken my own phone out to snap some pictures, though I wasn’t quite sure why. For this newsletter, perhaps? Or just because everybody else was doing it? Regardless, as soon as I started snapping, she jokingly put her hand in the frame. It was a silent but perfect act. It revealed that the faces weren’t grand and inevitable at all— they were inconsequential enough to be able to be blocked by a not-quite-teenage-hand. There was a time before they existed, and there will be a time when they’ll no longer exist. She didn’t need to make a scene to protest the ridiculousness of it all. The hand was enough.

Mount Rushmore is an abhorrent idea. There’s no reason for it. I’ve echoed that refrain for many self-satisfied decades. But that’s always been a selfishly easy stance, one designed primarily to stave off my own guilt.

The thing is, I understand why the big unnecessary mountain attracts an ideologically diverse crowd of seekers. I understand why we want to believe that there is a version of our country that doesn’t secretly break our hearts. What I wish for all of us, though, is something more than empty calories. I wish for neighbors and unions and political parties that see and care about us and also ask us to be better. I wish for honest accountings with our past and more empathetic dreams of our future. I wish that the Black Hills were returned to the Lakota and that our longings for a country worthy of monuments to be channeled into work together, rather than fairy tales. I wish for relief, but not escape.

End notes:

Do you know what makes for incredible reading (I hesitate to say as a companion piece to this essay, as it is incredible in its own right, but you get it)? Chris LaTray’s recent essay about the ways that American places reinforce- in their noise and their silence- that they aren’t for Indians.

As for a song of the week, would you rather hear me ramble on about broken treaties or would you rather hear a sample heavy track on the subject from Sincagu Lakota Rapper Frank Waln?

As always, the entire Song of the Week playlist is available on Apple Music or Spotify.

Less than a twenty minute drive away is the perfect "chaser" to Mt. Rushmore. Did you go to the Crazy Horse Memorial? We have been there twice and spent 3-4 hours each time. Fabulous museum, dance performances, history, all about the Indigenous in the area. It counteracts the Rushmore narrative and well worth a visit. Every tourist should see it.

Felt Nothing at Rushmore. Only spent 20 min after paying thru the nose for parking. Looks just like the post card, haha. Took one photo from the list of people who worked on it cuz the person had my husband's first and last name.

I struggle with "we" here, but I know your audience.