What did the boys do today?

My daughter, her father, and what to do about a nation of guys demanding attention

“So, do you think that having a girl will help you understand women better?”

The question came from a female colleague, less than a month after my daughter was born. It made me grimace, though I tried to hide it. I didn’t want the answer to be yes. I didn’t want to be like those conservative Senators who, when it comes time to discuss a women’s issue, affect a look of constipated Christian concern before intoning “… as a father of a daughter.” I wished that I could have replied convincingly that, while of course my daughter would influence my worldview in powerful and positive ways, she wouldn’t be the first woman whose perspective mattered to me.

It wouldn’t be until many months later that I realized that my colleague wasn’t really asking a question. She was casting a wish.

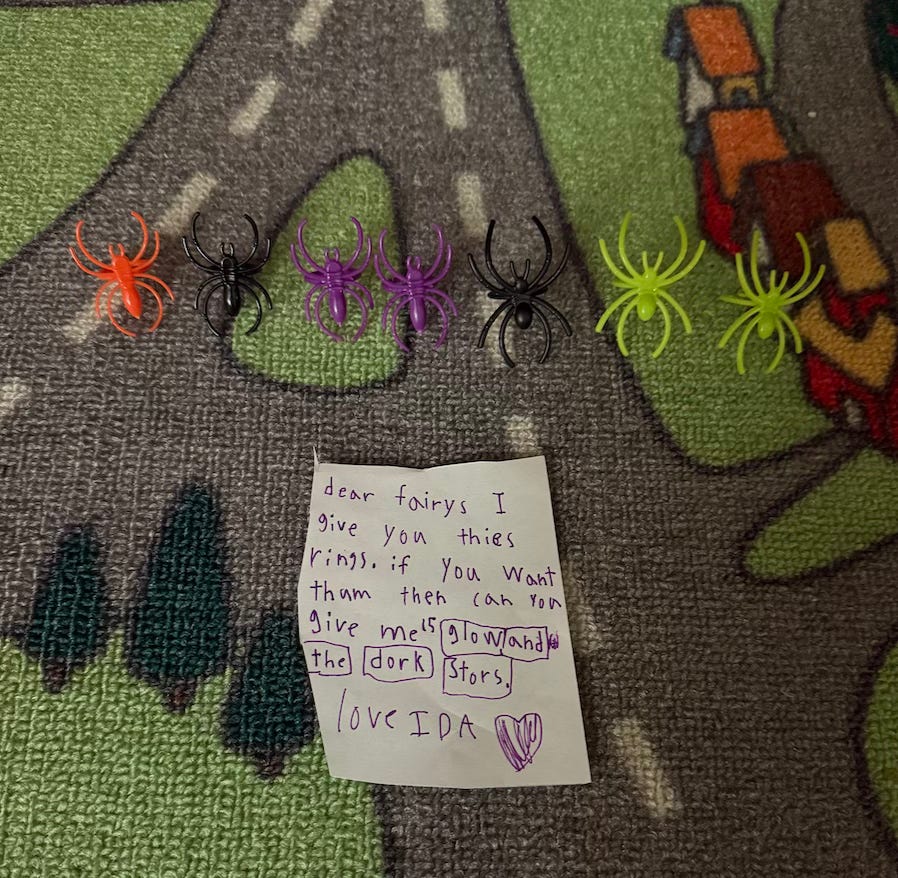

My daughter, Ida Jane, turns eight this week. Eight years is more than enough time for her to teach me a million lessons. When she was a toddler, she taught me that she could in fact pull off whatever feat of strength and daring that would follow immediately after she shouted “want to see my cool trick?” When she was three, she taught me the only dinosaur taxonomy I’ll ever need (there were three categories: “scary,” “fun to ride,” and “fun to ride with a blanket”). Just the other day, she taught me that if you want the fairies to leave you fifteen glow-in-the-dark stars (“they know I’m afraid of the dark, so they’ll understand”), you have to offer them something valuable in return. The lessons she’s taught me are big-hearted, brave-but-honest, and wise, just like her. If you’ve ever loved a kid— yours or somebody else’s— I’m not telling you anything you don’t know.

When my daughter started school, I expected that both of us would learn other, less-welcome lessons, about how the outside world reacted to her differently than it did to myself and her older brother. I was prepared, I thought. I had been listening to my wife. I had been paying attention to women in my life. I fully expected patriarchy to shape her life for the worse, but in a way that would be easily recognizable to her father. I expected her to come home with reports of direct misogyny: comments about her body or her abilities or how she was or wasn’t expected to compose herself.

All those expected affronts are coming, I’m sure. But up to this point, Ida doesn’t usually come home from school talking about what somebody said about her. She’s fortunate to have kind friends and affirming teachers and no small amount of class and racial privilege. As far as I can tell, nobody is directly dictating what she can and can’t be “as a girl.” At this point, the main problem isn’t how she’s being seen, it’s all the moments that she isn’t.

Most days, my daughter comes home talking about the boys.

“The boys couldn’t stop talking today.”

”The boys were having a rough day.”

“The boys were so funny on the playground.”

“Ugh! The boys were so annoying.”

“We didn’t get to finish math because of the boys…”

Ida Jane attends a legitimately diverse public school. The boys who demand attention are White and Black and Puerto Rican and Mexican, from families that have a bit of money and families that have none at all. Some demand attention because they have clear social or emotional needs, some due to generational trauma, some just because, well, attention feels great. She likes these boys. Many are among her closest friends. I know several of their parents. They’re nice. Lots of feminists. Lots of Will To Change on bookshelves. Most days of the week, there are just as many dads as moms at pick-up and drop-off. More likely than not, they chose our school community specifically because of its focus on social justice and open doors. When we learn that somebody’s kid uses different pronouns than the ones previously assigned to them, we pat ourselves on the back for how quickly we adapt. I’m sure they’re doing their best, these various boy moms and boy dads. It’s not all on them. I too was raised by feminist parents.

Some days the boys are fun or interesting. Other days they’re exasperating. But every day, my daughter’s implicit marching orders are the same. Adapt yourself to whatever space exists after the boys have claimed everything they need, be it time, energy or attention. Make do with the remainder.

Most days, she isn’t even complaining about the boys. She’s just narrating what happened.

“We had time for ______ today but not for _______”

“______ needed a lot of extra attention.

“Do you want to hear what _________ said today? It was soooo crazy.”

There are girls in her class who need more as well, who yell or shout or cry. But the louder refrain is about the boys. They define the space, she adapts to it. They shade in the center. She squeezes into the margin. She’s only eight, but she’s already learned the “not all men” fallacy. It’s not about which ones are directly mean to her; it’s about what remains after all the boys have taken their share.

Back to that question from my colleague. Yes, damnit. As it turns out, there was so much I didn’t notice until I heard it in my daughter’s voice. There is, no doubt, so much more I still don’t notice. She’s my younger child, by the way. Even if this was a revelation I needed to learn in parenting, it’s telling that it came through watching my daughter’s walk through school rather than my son’s. While I could flatter myself by pretending that I never asked “how much space are you demanding?” to her older brother merely because his teachers assured us that he was sweet and thoughtful, that isn’t the primary reason.

None of this should have been revelatory for me. I could have recited the most cogent lessons here long before I had a daughter: Feminism isn’t just about the messages you send your girls, it’s the messages you send your boys. Most of the thousand cuts aren’t committed by the most vile misogynists, they’re committed by the “good guys.” The story of privilege and power isn’t merely about what you’re given directly, nor even about what you don’t have to weather. It’s about the number of spaces you can float through without much care or consideration

Those are not, as it turns out, lessons that are mastered merely by knowingly rattling them off. There was a reason that a woman whom I worked alongside for years asked me that question about my daughter. She had, at that point, been forced to acquire a PhD. in watching me filibuster my way through meetings. She wasn’t curious about whether I would discover rape culture for the first time, nor whether I’d learn which slurs caused a woman the most pain. She was asking if I’d start noticing the people around me for a change.

We try to talk about this as a family. It’s not lost on us as parents that the things we’ve always loved most about both of our kids— my son’s sweetness and consideration, my daughter’s creativity and trust in her own voice— are both the traits most likely to be sanded down by patriarchy. It isn’t lost on me and my wife that they’re watching us for cues.

I’m glad we’re trying, but isn’t this always how it goes? A pernicious societal ill can only be reasonably processed as an individual family optimization project. Go to therapy, dads! Raise anti-oppressive children! Use Fair Play cards! Tell your daughter that she can be President and your son that he can be a stay-at-home dad!

When my daughter comes home with another report about “the boys,” I of course think about her older brother and myself and what lessons we need to take from this. But what is the United States of America in 2024 if not the sum total of a million spaces that get to be defined by and for the boys?

Us boys, we are told, are not receiving enough attention right now. We are feeling left out and lonely. Across racial lines, we swung right this election, voting for the only candidate brave enough to ask “what about the boys?” We are unheard, us boys, even though every media outlet continues to cater to us. The question du jour, post election, have been about “does the left need their own Joe Rogan?” a query that assumes that all men have an inalienable right to our own Joe Rogan. Pundits are filling the New York Times and The Atlantic with essays about who the Democrats should throw under the bus to make us boys feel more welcome. Should it be trans people? The next family who shows up at the border? All those ladies who were too loud about the abortion thing?

Never mind that the entire election cycle was about the boys, that masculinity was dissected in a million ways. Trump was a “man’s man” who “stood on business.” Tim Walz was “everybody’s dad.” Kamala Harris was a woman, but at least she had a husband and a Glock. Don’t worry, we were assured. She’ll fit into whatever space we’ll allow for her, nothing more.

I am immensely sympathetic to friends who, in the weeks after an absolute disaster of an election, are shouting variations of “enough with all the attention on the boys; we have been giving them sympathy for millennia now, and look where it’s gotten us!” I feel that impatience myself every day that Ida comes home with another yet another report from school, though in my case, largely because it’s easier for me to project the guilt I’m feeling onto a micro-community of eight-year-olds with Pokemon backpacks.

But there’s a paradox here, one that lives in the messy middle between not trying to chase good attention after bad and the fact that nothing can be changed until it is faced. Yesterday, while trying to make sense of all these swirling thoughts, I reached out to my dear friend

a brilliant feminist writer with a background in educational psychology/special education (and who, like me, is raising a boy and a girl). She said, in essence, “I’m glad you’re believing women about all the ways boys and men take up too much space, but clearly there’s a broader system that’s not serving any of these kids all that well… the solution probably isn’t just to make the parents of the loudest boys feel guiltier. The more important question is, what community do all those kids deserve and how do we imagine it together?”For years, the lingua franca of American progressivism has been about “centering” and “de-centering.” And again, there’s aspects of that framing that are tremendously helpful. But we’re in a mess that won’t be solved merely by a nation of boys being temporarily quieter, as cathartic as that proposition may sound.

There is a crisis in masculinity, but we delude ourselves when we pretend that it’s new. That crisis isn’t about our college matriculation rates or whether we’re “losing ground” to women in the workplace or how depressed we report feeling. The crisis in manhood runs parallel to the core dilemma of any privileged identity— Whiteness, straightness, economic advantage: We lose part of what makes us human when we’re given an out to pursue our own hero’s journey at the expense of others. I do think that “the boys” need to be heard, and we need people who are talking to them, but no more so than anybody else. In a world of precarity and disconnection, we all deserve a whole lot more seeing and hearing. Not all attention is created equal, though, particularly for those of us who have to learn a new way of being.

Eight years ago, a colleague who probably didn’t owe me anything at all asked me a question. At the time, I didn’t recognizing all that was underneath it— the call to community, to accountability, to curiosity. That move required her to pay more rather than less attention to a (not so young) man. But it was a specific type of attention. She didn’t ask me to wallow in self-pity about my manhood, nor did she ask me to develop a “new model” of masculinity. She didn’t care whether I went to therapy or not. She merely asked me to situate myself as part of a broader human ecosystem for a change.

We are told that the boys are alienated right now, and that very well may be true. I’ve spent a good percentage of my life pretty alienated, but not because my voice was never heard. Quite the opposite, actually. Alienation is another word for isolation, and isolation is what happens when you get to live your life outside of community accountability. The opposite of alienation is a relationship. The opposite of alienation is noticing who is made small when your energy fills a room. The opposite of alienation is giving a crap not merely about what you can get out of a space, but how you impact others in it.

My daughter turns eight this week. She doesn’t need any of the boys in her life to save her, including me. She’s really terrific, as are all the kids in your life, I’m sure. Even at eight, though, there are already spaces that could benefit from every ounce of her, but where she’s had to preemptively shrink herself down. And that’s a tragedy for her, but not just for her. Our community is stronger and more beautiful when she is trusted to show the best of herself.

We are right to focus on the boys right now, but not for the reasons we’re told. Boys and men deserve attention not because we’re uniquely sad, nor because we merely need to learn how to “be men” in a new and different way. It’s more complicated than that, because we’re trodding a new path, but it’s also quite simple. We need to respect boys and men enough to ask us to be human. We need to be asked, in all our shared spaces, to notice that there are others there with us. We need to be asked, not just what we need but how we could contribute to a world beyond the boundaries of our ego. We need to be trusted with the truth that, if we don’t rush to the front of the line, that there will be enough of everything to go around.

End notes:

As a White cis guy who writes on the Internet, I receive a tiny fraction of the trolling and abuse that women, people of color, trans people, etc. receive. I’m also fortunate to have a lovely commenters’ community here at the newsletter. It won’t surprise you, though, to learn that the comments I receive often get nastier (specifically from other men) when I write about gender. For that reason, plus the fact that I wrote about my own family today, I’m restricting comments on this one to paid subscribers. If you’d like to say something (or you’d like to participate in our other subscribers’ communities, which are indeed lovely) but don’t have the money, just email me at garrett at barnraisersproject.org and I will comp you, no questions asked.

If you can afford a subscription, however, know that it supports not just my writing but also all of the coaching, training and community building I do for activists (and would-be activists) across the country through the Barnraisers Project. We just finished a round of “what’s next” calls which were incredible. Thanks to the hundreds of you who joined (and who are now networking and scheming with each other). Thanks also to all the subscribers who enabled me to offer that space (and all my trainings) for free. While that round of classes is over, I’ll be announcing more soon (likely focused on a deeper “how to foster and strengthen local communities”), so if you haven’t signed up for the interest list, now would be a great time.

This piece feels like a companion to the one I wrote a few weeks back, about who is currently speaking to the boys and how it’s essentially the same people who’ve always been speaking to the boys.

Sometimes I think the thing that's so threatening for a certain kind of cis-gendered man (and some cis women, too) about trans folks is their deep insight into the performance of gender. That it is, in fact, a performance, rather than an inalienable, fixed reality, and like any performance it can be changed or transformed. The trans men I know who "pass", and so are privy to so many ways that men, particularly white men, perform for each other to prove their manhood, are the most insightful people I know about masculinity and how it can be performed in a way that shares space rather than dominating it. It's not that it's rocket science, really. It simply requires really deeply understanding all of the choices involved, which cis-men and boys aren't taught are choices.

And part of why my trans son, who doesn't pass at all, gets so much flack is because he is daring to perform aspects of masculinity that some cis-men want to protect as their inalienable right when they're really just play-acting.

If transphobic folks of both genders could get over themselves they really could learn so much about how to make social spaces truly gender inclusive from exactly the people they fear and despise.

Last week, my 4yo daughter and I had a discussion about how we can get her needs met without having to go through a universally-hated tantrum first, and I've been so proud of us: she agreed (and has been following through!) to specifically ask for parental attention before she makes a request for some assistance/thing so we have a chance to refocus attention to her, and/or let her know what we need to wrap up before giving her attention/when she could expect it. The past week has been virtually tantrum-free as she has discovered asking for attention works with more peace and effectiveness than her previous strategies...but now I'm wondering why I had to teach her to ask for attention, and that this was such a novel thing for us to implement when she has an 8 year old brother. Or maybe her needing this to be taught meant she's assuming she has all our attention all the time (a very 4 year old assumption, right?) and there's some power in knowing how to ask for it. (I'm going to go overthink this for a while now)