What I hope my (white, economically secure) kids are learning right now

On (perhaps not) Khan Academy-ing towards Bethlehem

Note: Growth curves being what they are, I have no doubt that near about everybody reading this has many more people in their lives impacted (either medically or economically) by Covid-19 then they did a week ago. Goodness knows I do. If you or somebody you love is feeling this tragedy acutely right now, know that I’m holding you in the light (and of course- if I can lend a hand, let me know). I want to acknowledge that it’s a privilege to be able to focus on coronavirus-adjacent issues rather than to sit in the eye of the storm. I write this not to deflect from immediate pain, but to help build a broader web of interconnectedness and support.

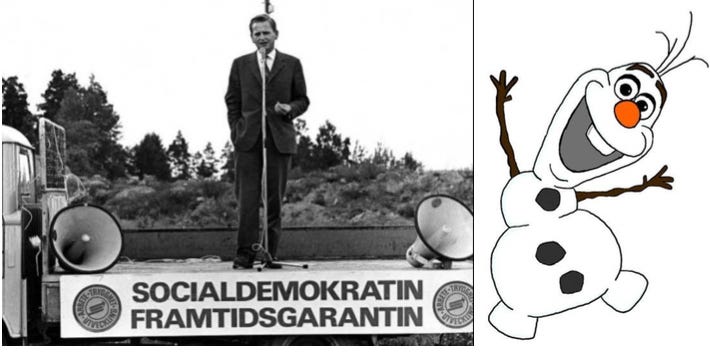

My wife and I didn’t even get through our literal first-ever decision as parents without the universe knocking us down a few pegs. You see, we were extremely particular about what we named our kids. She wanted something Swedish. I wanted to pay tribute to somebody meaningful. We ended up naming our oldest after an incredible former Swedish Prime Minister— an icon who had fought for economic justice and global human rights. We knew it was an obscure, inscrutable choice but it meant a lot to us.

My son was born in the spring of 2013. Six months later, the Walt Disney Corporation released a major motion picture about two sisters who struggle with poor romantic decision-making and debilitating ice-making powers, respectively. You may have heard of it. Fast forward to today, I can yell until I’m blue that my son’s namesake is Former Prime Minister Olof Palme and it won’t matter. He is instead forever consigned to a life of concerned questions about why his parents were such huge fans of a dimwitted but lovable cartoon snowman.

You shouldn’t take parenting advice from me, is what I’m saying.

With a few exceptions, American parents of school-aged children are now a week-and-a-half into the Great American Quarantined School Experiment. As the parent-at-home/current low-quality-teacher-of-record in my household, I hold no judgment for how y’all are or aren’t managing it. On one hand, everything is fine in our house. On the other hand I recently burst into tears for no specific reason midway through making a Taylor Swift song bracket with my kids. I’m not sure what happened there. The song playing wasn’t even “All Too Well.”

Whatever you’re doing or however you’re handing it, I applaud you. If you kept your children from actively licking public playground equipment or forcibly reopening libraries, prison-break style, good on you.

I should also make clear— I have no empirical evidence as to how other parents generally (and how white middle-to-upper-class parents specifically) are processing this moment. Like the rest of you, I only have enough energy at the end of the day for a few fleeting texts and a cursory social media scroll (this piece, if you’re wondering, was written in fits and starts over the course of a few late nights). And though the initial influx of Pinterest-ready color-coded schedule charts that popped a weekend ago was a bit intense, I’m fortunate to have mainly encountered other parents who are weathering their sudden conscription into teaching with self-effacing good humor.

I do know a thing or two about affluent white parents, though. I’m not surprised, then, that it already looks like many in our cohort are approaching this moment the same way we approach everything— with a combination of passive entitlement and knives-out competition. Here in Milwaukee, less than two hours after the Governor closed schools state-wide, white parents in one of our toniest suburbs had already organized a letter-writing campaign to their superintendent because he had not yet put out a robust virtual learning plan. Journalists and advocates in Michigan, Connecticut and Washington have documented the vast gap between the technological and pedagogical resources being showered on whiter, richer districts and those available to their poorer and/or mostly Black, Brown and Indigenous counterparts. Globally, it looks like the longer lockdowns last, the more likely elites are to shell out obscene amounts of money for private tutoring.

It isn’t just viruses that metastasize during moments of crisis— power and privilege has a way of seeping into new hosts as quickly as possible too.

There are few more insidious, dangerous patterns in American history than the way white parents relate to their kids’ schools. We may claim that we merely want our children to have a great education, but in practice “great” has always meant “comparatively better than, and definitely separate from, the education that less-deserving, be-knighted children are receiving.”

As Elizabeth Gillespie Mcrae showcases in her (excellent) Mothers of Mass Resistance— the true architects of white supremacist infrastructure— both in the South and North, weren’t solely or even primarily the traditional boogeymen (your George Wallaces, your Klan) but white mothers fighting for their kids. The nationwide legacy of white parents working to cordon their families off from undesirable (read, Blacker and Browner) classmates was so effective that it still shapes our physical geography today. It’s why cities like Indianapolis have a single municipal city-county government for virtually all services except for education (which is balkanized between nine townships and eleven school districts). It’s why nice white families in Atlanta opted for a lifetime of sitting in traffic so that their far-flung suburban enclaves can’t be accessed by trains from the city.

What we’re less likely to admit is how little the pattern of behavior has changed today. You can see this empirically, of course- in studies that show that white parents value diversity and equity in theory but still flock to privileged, homogenous schools in practice. The subtext of this hypocrisy, as always, is a battle between the values parents purport to having vs. their intense fears of having their kids be the ones left behind if they live those values.

Margaret Hagerman’s White Kids (the end product of her field work with white, affluent parents in a diversifying medium-sized city) is a treasure trove of a case study here. Seriously it’s so good. Hagerman focused her study on three distinct sub-groups of white families- one suburban, one in a crunchy leftist neighborhood in the city, the final one in a bougier part of town. She discovered massive distinctions between how the families talked about race— some leaning on color-blind rhetoric, others talking openly about privilege and structural oppression and the like. When she followed up with the kids in her study years later as teenagers, she found that the variance in these conversations did make a long-term difference in many of their racial attitudes.

What wasn’t different, though, was that in addition to the explicit message each set of parents sent about race, they also sent a set of implicit messages through the choices they made on behalf of their kids. Whether it was moving out of town for “better schools” or choosing a private education for a host of spurious reasons or fighting principals to ensure their sons and daughters would be cocooned in a safe cascade of segregated AP classes, there was a moment when virtually every parent in Hagerman’s study reinforced the belief their children weren’t just entitled to love and support, but to something separate and better than what Black and Brown kids received. This was true even for those parents who facilitated the most explicit family conversations about racism. Regardless of the efficacy of those conversations, their actions taught their children a different, more insidious message.

At the family-unit level, this race to advantage your own kids isn’t victimless, though it could be argued that its impact is hard to quantify. When those actions are multiplied at the community-level, however they are as effective at calcifying inequity as the white supremacist organizing of our foremothers and forefathers.

If you ask any principal, superintendent or school board member whose school or district includes a decent percentage of affluent white parents the biggest barrier to racial equity efforts, the answer will almost always be the same: One way or another, privileged parents will get what they want, and what they want isn’t equity for all. For more on this, I can’t recommend John Diamond and Amanda Lewis’ excellent Despite The Best Intentions: How Racial Inequity Thrives in Great Schools enough. Most notably, Diamond and Lewis demonstrate the way administrators are so attuned to elite white parents advocating/working-the-system on behalf of their kids that they have a tendency to just give new sets of white families what they want pre-emptively. If it sounds Pavlovian, it’s because it is. That’s what happens when powerful parents have a consistently narrow set of interests and know how to get you fired.

What’s tricky is the problem I’m ranting about is actually the sum of an equation in which one of the addends is malevolent (generations worth of internalized racism and entitlement) and the other one is benevolent (the intense love that parents feel for their kids). And oh goodness do I empathize with the latter. It is that immediate feeling you have right after your child is born, that “I am 100% willing to fight a bear to protect this human being” feeling. It is the intense jolt of fear you feel at random moments when they’re asleep and you convince yourself, without reason, that they may have stopped breathing. It’s the knock-you-down feeling of gratitude you feel when you sneak into their room to calm your anxiety and find them breathing deeply.

Goodness knows I’m empathetic to that feeling. That’s especially true in this moment, where all of our lives are reduced to the smallest possible household unit, where my wife comes home from the hospital each day and immediately throws her scrubs in the wash and takes a shower in a valiant attempt to keep us from getting infected. I lied up above— I know full well why a Taylor Swift song made me cry the other day. It’s because, hidden in a care-free, sing-song melody, she dropped in the line “I’d like to hang out with you… for my whole life” without any warning at all. And you just don’t do that to a scared/exhausted/grateful dad as he’s quarantine-playing with his kids on the living room floor.

The problem is, as I hope we’ve learned this week, it isn’t our job to just protect our own kids. It’s our job to build something collectively that protects all kids. And that’s where the more malevolent half of the equation comes rolling back in. Because us white parents can’t actually disaggregate our definition of what our kids deserve from a lifetime of self-serving, whispered stories that place us at the top of every hierarchy.

Full disclosure. I’ve actually cried twice this week and BOTH times it was because a stray lyric just landed an unexpected haymaker on me. The second one happened a couple nights ago. I was out on a late night run. The song was “The Night Accelerates” by Forgetters- a pretty simple Jawbreaker-adjacent three minute angry punk kiss-off. It is emotionally unfair that a song like that also includes the lyric “What if the life we tried to live was diametrically opposed to what everyone agrees is good, good enough for most.” But it does. And it floored me, a mile to go from home.

It’s ok to love my family deeply. The problem is when my actions teach my kids that ours is the only family worthy of love.

So here we are. I’m home with my son and daughter for the foreseeable future. They’re white, privileged kids, neither with an apparent learning disability. They’re going to be fine- not because of my brilliance as a parent or their innate giftedness, but because our world makes it so that kids like mine will have to work pretty hard to not have any future falls cushioned by their social position.

I’m responsible for their education now, likely for the rest of the school year. I definitely don’t know what that should mean for my three-year-old daughter (colors, I think? counting?). For my six-year-old son, I only sort-of know what that should mean. His is a high-poverty Title I school and district— they’re working their tail off just to feed everybody. Chromebooks for every student definitely aren’t in the cards. I’m not fully absolving myself of any academic responsibility— I have too much gratitude for his kind, hard-working teachers for that.

If my goal, though, is to enrich his way to continued academic triumph, to ensure that these next four months are the difference between Harvard and Vassar, I’m playing into a losing game. If ever there was a time to break the cycle of quixotically quantifying my love through the procurement of competitive advantages, it’s now. Plus, I know that like the families in Hagerman’s study, my kids will only learn a bit from the content I put in front of them (be that academic or sociocultural). They’ll learn a lot, though, from what they can tell matters to me, from how they see me spending my time.

So here’s what I hope my kids learn while we’re home together. Again, this isn’t going to come in the form of direct instruction, and there will be no quiz at the end (I can not stress this enough— I have a three-year-old and a six-year-old… let’s keep these expectations realistic). It’s a set of goals for what, years down the line, they can say mattered to their mom and dad, as shown by our actions :

I want them to feel that they are loved deeply and that I delight in being around them, but that they are no more delightful or worthy of love than other kids in other families.

I want them to process, alongside my wife and I, this specific moment when we’re consciously doing different, hard things to take care of our community. When this is over, I want them to expect that we continue to do so, but in response to more chronic threats.

I want our family to spend time creatively brainstorming ways to show care for our neighbors- both in the short-term and long-term.

I want them to know we’re a family that talks and thinks about unfair and painful systems that hurt some people more than others. I want them to know the stories of how that’s true across lines of race, gender, class, sexual orientation and gender identity.

I want them to wrestle, alongside their parents, with what it means to do things not because you feel sorry for others, not because you want to save them, but because you know them and think they’re great and truly believe that the world would be better with all of their gifts.

I want them to know that, as a family, we will hold each other accountable for using our voice to help systems work for everybody, not to hold onto our position.

I want them to understand that our family has been shoved to the front of a whole lot of lines in life and that we are still learning how to stop shoving to keep those positions.

For the first time in my kids’ lives, they’re in a moment where everything in our family’s world is focused on the common good. I won’t be doing right by them, their classmates or any of our neighbors if I allow this first time to be the last. Here’s to showing not telling. Here’s to loving our family hard but not stopping there. Here’s to fighting pandemics that hurt us in a single moment and systems that hurt us for a lifetime.

End notes:

If you’re interested in connecting with other white families trying to be more responsible members of their communities, please check out the Integrated Schools community (but be patient in the short term— the volunteers who run it are also running home schools right now).

I telegraphed this week’s songs of the week already, but for the record, they’re “Stay Stay Stay” by Taylor Swift and “The Night Accelerates” by forgetters

Photo credits here.

I stole the Taylor Swift song bracket idea from Tom Ziller’s indomitable NBA newsletter This Morning In Basketball. My kids had a blast with it.

My wife and I still love our son’s name by the way. We also don’t mind the snowman.

God this is good. Thank you Garrett.

To quote you: "They’ll learn a lot, though, from what they can tell matters to me, from how they see me spending my time." Do you only have love for your family and your people, or do you love everyone and want all to succeed? The past couple of years have been a perfect time to examine how we relate to others outside of our immediate circle. Where we choose to live certainly can act as a bubble or inner circle. If you don't see it - it doesn't exist - which is also true for our children's schools. We lived in downtown Atlanta and still managed not to understand what other families really went through just past the dividing highway. You want the best for your children - yes of course - but don't some of us have enough? Time to give back and set a more level playing field. Maybe we can stop thinking about which college they'll go to and start thinking about what kind of person we are raising to begin with.