"What kind of man are you?"

A White Pages Summer Movie Series Guest Post: On Twelve Angry Men and what it takes consider new truths

Top note (from Garrett): Greetings from Sweden, a place that is full of friends and family and is super important to my wife and kids (and me!). It’s such a joy to hand the reins over to

this week. Lynn is the author of the terrific newsletter, a deeply thoughful and highly practical activist publication that I always love reading. What I appreciated most about her take on Twelve Angry Men is that it resisted the easy contemporary “this is just a White guy savior story” critique to instead play with what the classic film still asks of its viewers. I love how she connected with the text as a lifelong educator in particular. More thoughts below, but in the meantime, enjoy!I grew up in the 60s and 70s, on a diet of bad television, boil-in-bag vegetables, and movies that sometimes lacked a single female character. For a long time, my favorite film was The Great Escape, a heroic story based on real prisoners of war from Allied nations who tunneled out of a Nazi camp to freedom using their strength, courage, wits, and incredible resourcefulness.

I was fortunate enough to teach humanities for eight years with a man who has all of these qualities, although he’s more of a moral courage guy than the type who hops on a motorcycle to evade Nazis. Together, we taught many books, including Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Esmeralda Santiago’s When I Was Puerto Rican, and Junot Diaz’s stories in Drown. The theme of manhood was potent for our students who were, like all of us, products of a patriarchal society.

Occasionally, we would show movies. [On reflection, I realize that we mostly showed the work of male writers and directors. Some exceptions I recall are Barbara Kopple’s Harlan County, USA, Mira Nair’s Mississippi Masala, and Silkwood, which was written by Nora Ephron and Alice Arlen.] Sometimes we showed familiar titles, like Spike Lee’s Crooklyn and Do the Right Thing and Rob Reiner’s The Princess Bride.

Our goal, however, was to show movies that our students were unlikely to have seen and would enjoy. We showed arty, surrealist films like Jonathan Demme’s True Stories and tried to open up our students’ ideas of what movies could be and what humanity looks like with John Sayles’s Brother from Another Planet. We showed black and white films like Fred Coe’s A Thousand Clowns Times, and Sidney Lumet’s Twelve Angry Men.

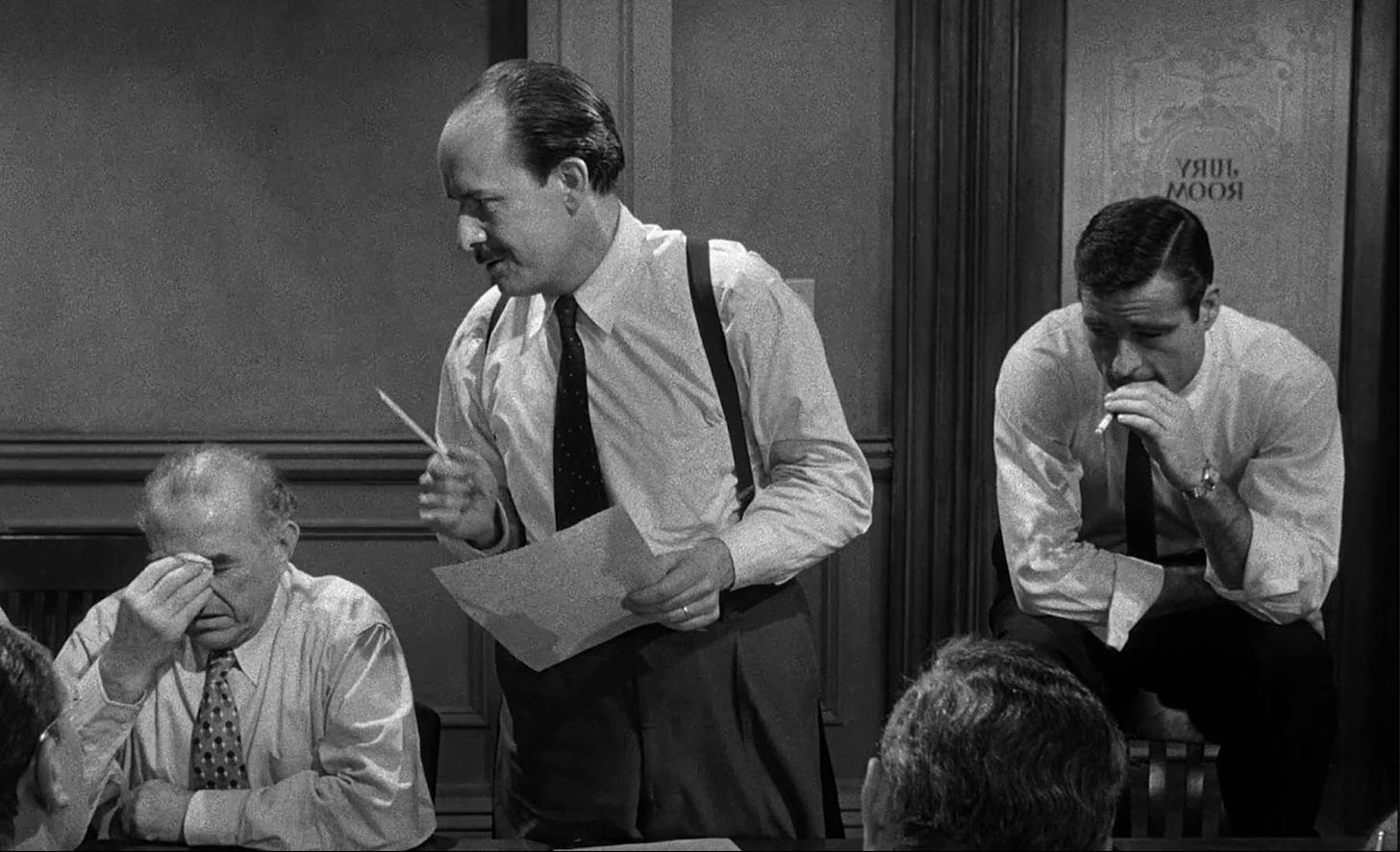

Twelve Angry Men (1957) tells a complex story of character and duty. The action centers on twelve ordinary New Yorkers gathered in a sweltering jury room to decide the fate of a young man accused of killing his father.

The film stars Henry Fonda, who plays Juror #8, an earnest man who asks his fellow jurors to entertain the possibility of a not guilty verdict. Again and again, Juror #8 asks, “Isn’t it possible?” His question is larger than the question of reasonable doubt, of guilt or innocence. Really, he’s asking us if it is possible to be the kind of humans who recognize the humanity in others.

Juror #11, the lone immigrant on the jury, reveres the democratic traditions of the United States and asks a question that drives the film’s storytelling and each of the characters:

What kind of man are you?

The crime itself is loaded with symbolism. Fathers in the era when this story was written — first as a play in 1954 — were a different breed from fathers of today. They were accorded more deference and were more likely to be revered or feared or both. Fathers also bore a heavy burden as breadwinners and protectors of their families, as role models and even heroes to their children.

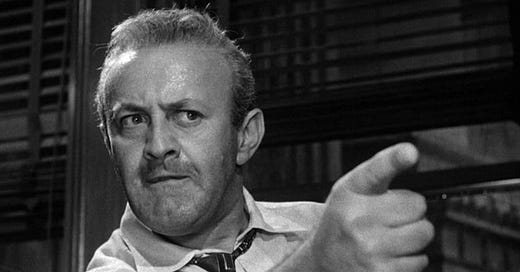

Lee J. Cobb plays the angriest of the men. Cobb’s Juror #3 runs a messenger service, telling another juror that he “started from nothing.” He laments that kids used to call their fathers Sir.

His anger is focused on his son, who ran from a fight when he was a kid. On that occasion, he told his son he would “make a man out of you if I have to break you in two trying.” What he broke was the relationship. We learn that he hasn’t seen his 22 year-old son in two years.

The story of Twelve Angry Men is a story of psychological baggage as much as it is a story of social and criminal injustice. Every juror enters the room burdened with his injuries, his biases, and the world view that grew out of his experiences.

The jurors gradually reveal themselves. It is striking that in a group of actors who are all White, the story manages to comment so effectively on racial bias. Juror #11, played by the Czech actor George Voskovec, and John Savoca (or Sacova), the uncredited actor who played the young man on trial, are the only characters distinguished by ethnicity in their accent or appearance.

The movie gives us a picture of White men shaded by class and temperament. This is something, I fear, that has been somewhat lost to us. When a more diverse set of characters are introduced, the bias and stereotyping that White filmmakers attach to Black, Brown, and Indigenous characters also flattens out White characters. The harm of racism is not equally distributed, to be sure, but it is deleterious to everyone who wishes to be understood as a complex human. This is not a reason to tell more stories with all White characters, just an observation.

Juror #1, portrayed by Martin Balsam, is angry because his leadership is questioned and he lashes out at the other jurors, demanding to know if they feel they could do a better job as foreman. He is the head coach for a team of boys in Queens, and he falls into an extended sulk after the disrespect shown to him by some of his fellow jurors.

Juror #9 is the old man. He is bald and alert like a baby, and he brings curiosity and wonder to the proceedings. He is the first to join Fonda’s Juror #8 in voting not guilty, and he does so in recognition of the courage it takes to stand alone, asking questions. In contrast, Juror #12 is the slick adman, an ‘idea’ man who does not know what he thinks.

E.G. Marshall’s Juror #4, prim and bespectacled, is a man of reason. He is educated, confident, and remote. He grows angry when interrupted by the old man, Juror #9. He is not accustomed to being interrupted or to being wrong, although he changes his vote when he sees that there is reason to doubt an eyewitness who wasn’t wearing her glasses when she saw the murder through the windows of a passing elevated train.

Jack Klugman’s Juror #5 grew up in a slum. He bristles when others disparage the defendant as a slum dweller, saying, “Perhaps you can still smell the garbage on me.”

Jack Warden’s Juror #7 embodies what Hannah Arendt termed “the banality of evil.” He is a “terrifyingly normal” man, whose thoughtlessness is more remarkable than any evil intentions or motives. At first, he seems merely unserious, eager to get to the ballgame that evening. He is a salesman, who relies on jokes and tricks to win customers. The product, incidentally, is marmalade, something bitter concocted into something sweet.

He ridicules Juror #11, the immigrant, for coming to the United States from Europe as a refugee and then turning around to tell Americans how things should work. His anti-immigrant screed, which is short and comes late in the movie, stands out as a powerful reminder that the Great Replacement fears among White people are old and deep.

Juror #10, played by Ed Begley, is plagued with a terrible cold and the ancient ailment of prejudice against the poor. He refers to the defendant repeatedly as a “born liar,” and he claims that it was “obvious [that he was guilty] from the word go.” He eventually delivers a lengthy rant, so filled with hateful assumptions that all of the other jurors turn their backs to him.

During hours of deliberation, Fonda’s Juror #8 repeatedly asks the others, “Isn’t it possible?” He means to find out if the others will consider the possibility of an alternate narrative, in which the boy did not murder his abusive father. He is raising reasonable doubts. He is also asking his fellow jurors to put aside their prejudices and anger — and in doing so, he is modeling what both jurors and human beings should do.

Ultimately, the men in the jury room recognize that there is reason for doubt. The young man may have killed his father, but the elderly neighbor who claims to have heard the body hit the floor could not have reached the hallway to see the murderer escape. The woman who identified the son as the killer could not have done so without her glasses on. The downward angle of the knife wound was unlikely to have been made by the young man’s switchblade, as such knives are typically used with an upward thrust.

We are living in a time when some people want to make facts seem unknowable. And for many people, our selves are also pretty mysterious. We are not all intrinsically motivated to examine our own biases and baggage. At the same time, we want to be treated fairly and most of us think we are fair-minded.

The initial vote in the jury room was 11-1, in favor of a guilty verdict. The witness testimony and the circumstantial evidence point to the dead man’s son, who had argued loudly with his father and yelled, “I’m gonna kill you!” on the evening of the murder.

It is easy enough to bypass the weakness of the evidence when the story you’ve heard comports with your own assumptions. Sometimes we just don’t care that much about the facts; other times, the matter in question feels personal, and that complicates our perception of them.

It is different, however, when it is your job to examine the facts. Jury deliberation entails lengthy discussion among a diverse group of people. I believe in the power of such interactions. We do not create enough opportunities to engage in this way with one another, with facts, and with our own imperfect understanding of the world. Only rarely are we locked in a room where it is our duty to do so.

My long-time teaching partner and I built text-based seminar discussions into our courses. Although we did not lock our classroom doors, it is in the nature of compulsory education that we were able to set protocols for discussion that required students to ask questions of each other, support their ideas by citing text, and use active listening techniques to check their understanding. We believed then and still believe that the methodology was invaluable for teaching humanities and for helping our students to apprehend the world as listeners and thinkers — and to better understand themselves.

I have used the word believe intentionally. Beliefs were always involved in our seminars. While we chose the texts and the questions to be discussed, students occasionally challenged the premise of our questions. They always discussed their own beliefs and the ways in which those beliefs shaded their understanding of the texts. That was their job on seminar days. Sometimes they did it grudgingly, like Jurors #3 and #10. There were some students who yielded a point because they were unable or unwilling to formulate a coherent reason for their disagreement with the group, much like Juror #7. And there were students like Juror #12, who never knew what to think.

On the best days, minds and hearts opened. We shared new understandings of what we were reading and why it meant what it did to us. We learned a little more about what kind of people we were and what kind of people we wanted to be.

The jury in Twelve Angry Men confronts the humanity in each other and in the young man whose life they hold in their hands. Together, in that sweltering room, they put their anger and prejudices aside to consider an alternative narrative, one in which things are not as open and shut as they first believed. It is a powerful story for our times.

End notes:

Again, thanks to Lynn Yellen for the guest post this week. Definitely subscribe to

and also check out her voter readiness workshops (if you’re interested in those, you can email her directly— esalynn@gmail.com).Thanks also for your continual support of my work, either through opting for a paid subscription (see that link above? it works!) or buying The Right Kind of White, a book that is still available wherever books are sold but is definitely available at this link. Shout out C-Span’s Book TV for broadcasting my launch event from March (as well as all those of you who have written me to say “I saw you on Book TV”- I promise to reply to emails after vacation)..

Paid subscribers, I haven’t decided as to whether Thursday’s post will be a community discussion or a semi-private “thoughts and pictures from Sweden” vacation update. I plan to follow the vibes.

Next week? The movie series continues with another guest post, this one on Clueless, another film whose protagonist makes an inspiring speech appealing to her peers’ better angels (I’m talking about the Ha-tian dinner party speech, of course).

I admit I have only seen it as a play and not the movie but it is great to be reminded of how so many of the themes and characters are still so resonate today. I find myself imagining how you might embody the ethos of each of those jurors in 2024 - a world of online masculinity influencers, of disillusionment with meritocracy and a faltering middle class, and a climate of hyper-partisanship.

I love the aspiration behind the phrase, "asking us if it is possible to be the kind of humans who recognize the humanity in others."

This was excellent. Thank you for the thoughtful insights. I love the guest column/commentary idea, Garrett. Diversity of thought!