What we talk about when we talk about how "he hated Black people"

Thoughts on a hate crime, a few days after the news cycle has moved on

Top notes:

Thank you for your patience with a logistics-heavy period around these parts. On one hand, we are in Barnraisers Project enrollment season (the cohorts I offer where we learn to organize for justice in predominately White communities). They are so much fun and I hope you consider joining us (enrollment closes September 8th, cohorts start the week of September 18th, that link has all the information you need).

But wait, there’s more. As I announced last week, my book, The Right Kind of White, is now available for pre-order and there are some very fun gifts to be had if you do so.

And then, in the midst of it all, is this newsletter, which only exists because readers band together and help me afford child-care. I really do believe that this space offers a conversation that is unique and important (and that I know has been helpful to a whole lot of folks) and I’d love to keep it going. Thanks in advance for considering supporting. It means the world to me.

Look at that! I’m getting better at sharing both what I have to give and what I need from others directly and not passive aggressively. Progress! Thanks, you all. If there’s anything I can do for you, let me know. Mutual aid isn’t just a buzzword.

I visited my wife’s family in Southern Minnesota this past weekend. We ate Swedish pancakes stuffed with berries and cream and I watched my kids ride up and down my in-laws’ driveway on bicycles that once belonged to their mother and aunt. We drove up to the Cities to watch a professional soccer game in a stadium that looks like a giant alien spaceship landed across the street from a Culvers. I had multiple conversations with Minnesotans about the two topics that you are required by law to discuss in the waning days of a Minnesota August (namely what everybody thinks of the State Fair, and what everybody is going to eat at the State Fair). The heat dome that had suffocated the Upper Midwest earlier in the week had broken, so it was mild and sunny and school hadn’t started yet and truly… what more could you ask for.

It was the kind of weekend that would have been light and care-free, except that’s not really how life works, at least not in the world we’ve all inherited. The small city where my in-laws live is both a relatively sleepy college town and also the place where 38 Dakota men— POWs from Little Crow’s War— were once hanged on direct orders from the Great Emancipator himself. We all contain multitudes, but more often than not White America only contains one thing.

During lunch on Saturday afternoon, I asked my mother-in-law what she thought of the movie Oppenheimer. The conversation got heavy pretty fast, which I should have anticipated. Oppenheimer is a movie about racing against Nazi Germany to build a world-destroying weapon. That was on me. And so, while spreading Miracle Whip on a Cub Grocery kaiser roll, I listened to a gentle-voiced, retired middle school teacher— a woman who makes my children feel safer than anything in the world— reflect on a lifetime of watching loathsome men commit acts of evil and wishing that some all-powerful protective force would stop them in their tracks.

I chewed my turkey and cheddar sandwich thoughtfully and listened to my mother-in-law talk about monsters. After she finished she asked me— politely, not unfairly— how my wife and I could be pacifists. I wasn’t offended. Part of what you sign for when you commit to that particular ideology is the constant reminder that you are out-of-step with the world.

That night, after putting my children down to sleep in beds overflowing with treasured family stuffies, I checked the news and learned that a White supremacist in Jacksonville had gone on a murdering spree. I learned that three Black people died— they would eventually be identified as Anolt "AJ" Laguerre Jr., Jerrald De'Shaun Gallon and Angela Michelle Carr,. I learned that the killer— a twenty-one-year-old named Ryan Christopher Palmeter— had a manifesto, a troubled past, and a gun with a swastika carved on it.

I jumped from article to article. Every single one made a point to share an identical quote from Jacksonville Sheriff T.K. Waters’ press conference.

“The shooting was racially motivated, and he hated Black people.”

That phrase kept rattling around my head for the rest of the weekend. It was my internal soundtrack as I piloted our family’s Prius down Interstate 94, homeward through the Driftless. It stayed in my head through Monday night, when I tried write this essay, my concentration interrupted by news about an entirely different horrific shooting (the victim was a Professor in Chapel Hill, North Carolina; there are videos of college students jumping out of windows to escape). But whatever other stimulus came my way, that sentence remained.

“He hated Black people.”

On the face of it, there’s absolutely no mystery to that phrase. Palmeter was a manifesto-scrawling racist, a vehement White supremacist looking to impress other vehement White supremacists. He hated Black people because that’s what it means to be a vehement White supremacist.

Before I go any further, a quick reassurance. This isn’t one of those essays where a smug writer who has attended too many diversity and equity trainings (read: me) pushes his glasses up before pointing out that not all White supremacists wear hoods and murder Black people. That’s the “White supremacy is an ideology that shapes all of our lives” lecture. It isn’t wrong, but it is slightly reductive. As much as I love criticizing my fellow White people’s voting habits, school choice decisions and workplace weirdness, I don’t pretend that there aren’t levels to this. The threat posed by White supremacists who open fire on grocery stores in Black neighborhoods is more acute and terrifying than that posed by an annoying nonprofit boss.

Just because two actions aren’t morally equivalent, though, doesn’t mean that there isn’t a connective thread. I suppose that’s why I kept thinking about that sentence, the one about how Palmeter hated Black people. It’s too clean, too exonerating. “Nothing to see here, ladies and gentleman,” the detective reassures the crowd, “the madman acted alone.” It left me with a bad feeling in my mouth, one exacerbated by the cowboy-bravado of Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, who called Palmeter a “deranged scumbag,” a “lunatic,” and a “coward.” Real black hat/white hat stuff. Condemn and advance. Mission accomplished

Another quick aside, on DeSantis this time: I can’t wait for the day when he finally disappears from the American political scene, just a cloud of ambition and self-regard floating out of our consciousness. Until then, I fear that he will find his way into just about every American news story. I understand the desire to tie the thread from Palmeter to DeSantis and stop there. It is true that DeSantis declared that Florida was where “woke comes to die.” It’s not coincidental— given his rhetoric and policies—that actual human beings are also now dead on DeSantis’ watch. He was booed the other night (at a vigil for the victims) which feels appropriate. But we’d have a simpler problem on our hands if this too was just one Governor’s fault.

What does it mean that the gunman hated Black people? What does it mean to hate an entire group of people?

Sheriff Waters said something else about Palmeter’s manifestoes that feels telling, whether it was intentional or not. He described those missives as both “irrational” and “100% lucid,” which is another way of saying that they were reprehensible but with a clear narrative throughline.

“He hated Black people.”

There are only so many reasons why you might develop an all-encompassing hate for another group of people. One is if that group acted en masse to commit terrible and unthinkable acts against you. That’s relatively rare, though. The far more common reason has nothing to do with the people being demonized. It’s when you hate another group because their resilience, their joy, and their glorious existence is impossible to square with the stories that have animated your life. It’s when you hate a group for what they reveal about you. Hate is one way human beings react to truths we can’t metabolize, but there are others as well: Performative guilt, tokenism, “listening and learning.” We’ve got lots of tricks. Some are deadlier than others. None are helpful.

Toni Morrison wrote a book about all of this, of course. It’s called Playing In The Dark and while it’s a work of literary criticism (it has its roots in a series of lectures Morrison gave on the way in which Blackness shows up in the White literary canon), it is equally applicable to White people more generally. Per Morrison, White authors are always writing about Blackness, whether they know it or not, because there’s no way for Whiteness to define itself except in opposition to its shadow. Nowhere is that Morrisonian shadow clearer than with overt White supremacists. That’s their whole animus— to create an entire ideology around the myth of Black inferiority so that they can both justify the leg up that Whiteness has provided them while receiving a salve for their immense self-loathing.

Whitnesss doesn’t just define itself in opposition to Blackness (and Brownness and Indigenity) though. The White supremacist murderers are themselves a useful shadow for the rest of White America. They pop up to the forefront of our collective attention every few years— sometimes in a flurry of bullets, sometimes clomping their Tiki torches through Charlottesville or picking fights with Antifa in downtown Portland. That’s why I try to resist the reductive flattening of White supremacy into a single story rather than a mobius strip of action and reaction. The overt supremacists are the monsters White people need when our fear of our own monsterousness grows too unbearable. I am more likely to continue with my life-as-it-is—with all of its moral hypocrisies and brave stances not taken— thanks to the relief valve provided to me by the Palmeters of the world.

One of the most remarkable books about race that I’ve read in the past year is The Inheritors by Eve Fairbanks. It’s about the generation that came of age in post-apartheid South Africa, and it shines thanks to Fairbanks’ ability to get her sources— especially her White sources— to admit to truths that so often go unspoken by their settler colonialist compatriots in America.

There are so many fascinating threads in The Inheritors but the one that stuck with me the most is when Fairbanks’ White interviewees talk openly about their psychic resentment of Blacks for not seeking full, bloody justice for the sins of apartheid. The fact that Afrikaaners received the gift of reconciliation and detente rather than mob action in the street meant that they had to actually sit with their guilty consciences, that they had to live in the reality that they were co-conspirators in something heinous and inhumane. As one of the book’s primary subjects puts it, "How dare you [Black South Africans] hold up a mirror of graciousness that shows me the reflection of a worse man than you?"

White people in America usually don’t admit to that particular gut-rot feeling. We lacquer it over with more palatable, twee terms like “White guilt.” But every time I’ve had a conversation with another White person that gets down to the core of our thoughts on the matter, that’s where we finally land. We are part of a monstrous system. We are the machine. We deserve the fate that James Baldwin once famously prophesied “No more water, the fire next time.” We’ve earned a mass rebellion against Whiteness, an overturning of all the tables upon which we sit. And yet again and again, we receive more kindness and graciousness than we collectively deserve. And central to our shared experience of Whiteness: we hate ourselves for it. We usually don’t admit that consciously. Most of us deny that self-hatred vehemently, in fact. But it is the indelible bond of Whiteness.

It is onto that collective morass that— every few years or so— we process news of a White supremacist atrocity. And once again, all White people are not exactly the same as the gunman, but there is a web that connects us to him. That web is not just intellectual but emotional. And the existence of that web feels unbearable, but it also offers a sublime opportunity. There has been an immense beauty in all of those conversations I’ve had that end with “oh my goodness, are we really the monsters?” There’s always been an ellipsis there… an opportunity to ask the next logical question.

“So what would we do if we didn’t want to be monsters?”

What a tragedy, then, that we so often miss that moment. The White supremacist is so obviously repellent, his hatred so calcified, that we can convince ourselves that the web between him and us has ceased to exist. Like DeSantis, we condemn and advance. The news cycle moves forward (I am writing this three days after Palmeter’s terror attack; the news cycle has already moved forward). We go back to our lives of status chasing and achievement, of limited sacrifice, of neighborhoods either segregated or gentrified but always built in our image, of children sent to schools with a bare minimum of poor Black and Brown classmates, of racial reckonings time-stamped and checked-off (“remember in 2020 when racism was an issue?”).

In the meantime, the thing-that-we-call-guilt-but-is-actually-something-deeper slowly grows back again, waiting for another sin-eater to deflate it.

I was immensely grateful that my mother-in-law wasn’t Minnesota nice to me during that Saturday lunch, the one where we ate impossibly bready sandwiches and considered human beings’ inhumanity to one other. It didn’t make the weekend any less lovely, because that’s not how life works. We love and are connected to each other, and part of that connection is that we are actually scared to death.

We are scared of the monsters that live out there, of course, but that’s not all. We are scared—particularly those of us with hierarchically powerful identities— of the monsters we are. And that shared overwhelm is one of our bonds, but not our only bond. We are also desperate for something different, for a world that makes all of us less monstrous. And that’s what we don’t talk about when we talk about how the gunman “hated Black people.” That’s what we miss when the cameras disappear and we move on to the next one— the next indictment, the next Presidential horse race analysis, the next reactionary country hit. There is power in sitting in the morass, of sitting in the unspoken. It’s not about suffering for suffering’s sake. It’s the fact that it is those moments, when we finally admit that we don’t know what to do (with the world, with each other, but especially with ourselves) that we are more likely to turn to one another.

End notes:

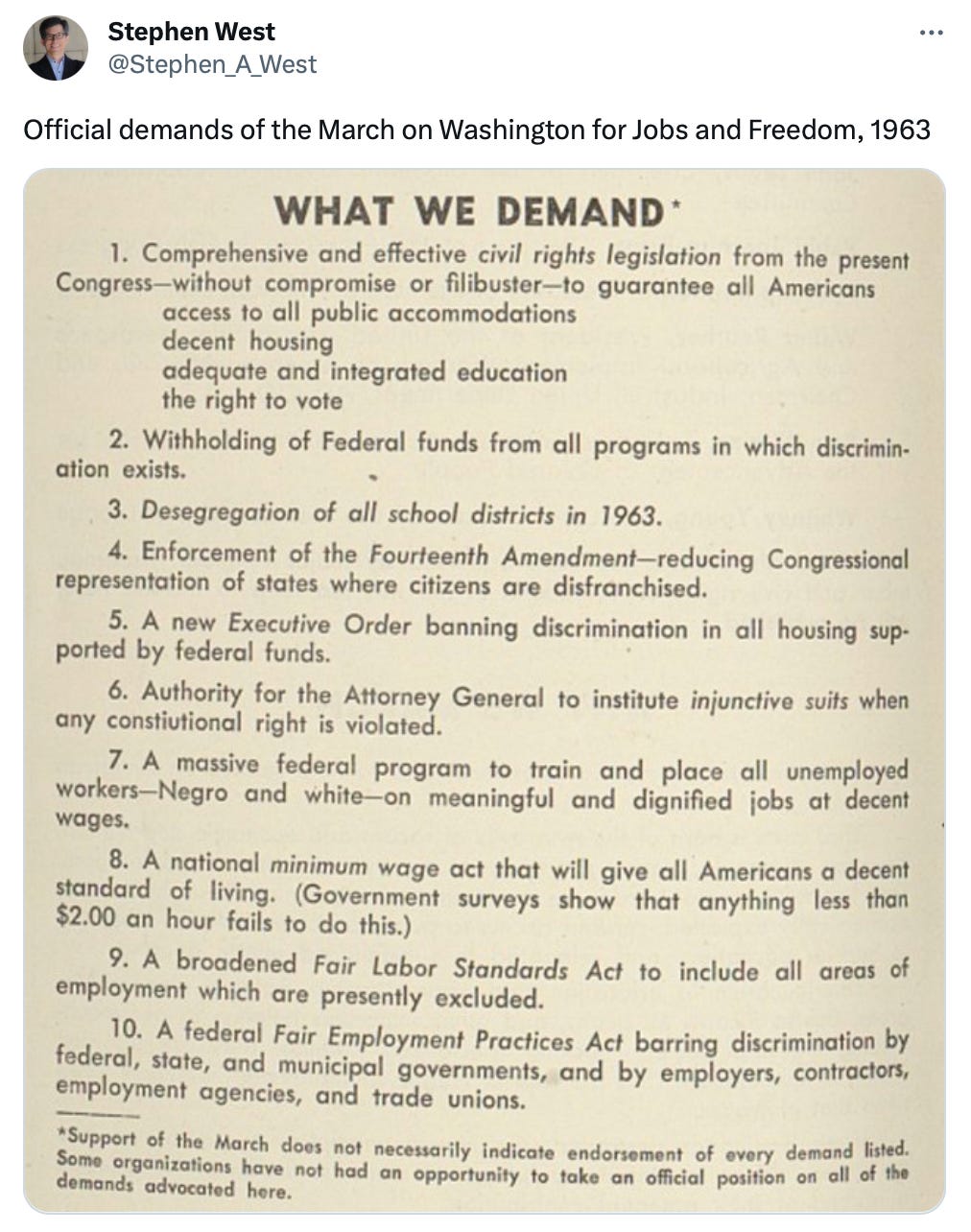

It is the anniversary of the March on Washington. Here are the demands from that action. How are we doing?

Song of the week:

While I kept thinking about that line from the Jacksonville Sheriff, the other soundtrack in my head was the new Zach Bryan. I listened to this one specifically (“Overtime”) over and over while washing dishes at my in-laws’ house. It helped with that whole “feeling like you’re a part of a web of belonging” thing, at least for me. Maybe it’s this line:

“No matter who you know no matter what you do/ I’ll become what I deserve when it’s all through”

Also, I’m saying this to hold myself accountable. I WILL update the Song of the Week playlist, which, as always, is on both Apple Music and Spotify.

As someone born and raised in Jacksonville, and educated in its integrated public schools in the 1970s and 1980s, I appreciate this thoughtful reflection so much. "Lift Every Voice and Sing," the Black National Anthem, was composed and first performed in Jacksonville. The city is rich in Black history, and has a growing Black population that is increasingly influential both politically and economically.

No doubt, Florida's largest city is changing, and the White supremacists -- of all varieties -- are very worried about what it means for them, though many of them no longer live in the city itself (which is one and the same with Duval County). Palmeter, who was from neighboring Clay County, was one of many White folks living in the mostly White counties bordering Jacksonville and, from afar, decrying it as a crime-ridden wasteland while barely hiding the racist undertones of their laments.

The latest wave of White flight has, indeed, left many holes in the fabric of the city, but it's hardly a crime-ridden wasteland. Quite the opposite. Its population is growing, with a burgeoning Black middle class and immigrants from Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. Jacksonville just elected their first woman mayor -- a (White) Democrat -- and the county went for Biden in 2020. There's even a big, beautiful new park named for "Lift Every Voice and Sing." For sure Black folks in Jacksonville aren't apologizing for their resilience, joy, and self-determination. But the surrounding counties are deeply conservative and pro-Trump & DeSantis. It makes for a tense mix sometimes, with those folks on the perimeter looking at Jacksonville as an avatar of what the right wing has convinced them is "wrong" with this country. Palmeter was sadly not at all unique in his views, and I fear he may not remain alone in his actions. Florida under DeSantis is a frightening place for a lot of people and for a lot of reasons.

I think you're totally right that these violent extremists are a kind of release valve that -- on some level -- helps us feel less awful about our own internalized racist attitudes and behaviors. "I may not be perfect, but at least I'm not THAT guy." For that small, cold comfort, Black folks pay with their lives. But how many "release valves" are too many? When will we decide that enough is enough?

Thanks for the book rec. “The far more common reason has nothing to do with the people being demonized. It’s when you hate another group because their resilience, their joy, and their glorious existence is impossible to square with the stories that have animated your life. It’s when you hate a group for what they reveal about you. Hate is one way human beings react to truths we can’t metabolize, but there are others as well: Performative guilt, tokenism, “listening and learning.” We’ve got lots of tricks. Some are deadlier than others. None are helpful.” Thanks for writing this.