Why not you?

Maybe it isn't time for you to build something new that would make your community better... but maybe it is

TOP NOTES:

Thank you, sincerely, for reading The White Pages. It means a lot to me. This newsletter is one part of the organizing I do with The Barnraisers Project (speaking of which, new training cohorts kick off the Week of September 12th! Registration will open next week! You can read about them here; they’re super fun).

This (both the training and this writing) is the best way I’ve found so far to be useful to and with others. If you agree, and especially if you’ve benefited from it, I’d love your help in keeping it going. Thanks in advance for sharing, for reaching out with reactions and, if you’re able, for becoming a paid subscriber (and/or donating a subscription for somebody else!).

As for other things that I think are worth your support that aren’t about me, this week I’m gonna pitch in to help a couple of the requests that are being compiled by Eastern Kentucky Mutual Aid. I invite you to do so as well (you can learn more about the why and how of their disaster response on their Facebook and Twitter).

I was jubilantly, ecstatically happy this past weekend. That’s no small feat, since, recent good electoral news notwithstanding, we are currently experiencing One of Those Summers1. I wasn’t jubilantly, ecstatically happy because I was closing my eyes to a world full of fires and floods and (multiple!) pandemics and (even more multiple!) authoritarians consolidating power. I was jubilantly, ecstatically happy because my neighbors had offered me the opportunity to feel a bit less alone, a bit less ineffectual, a bit less selfish.

It wasn’t world-changing, this invitation. To be honest, it wasn’t too different from the kind of twee, self-consciously quirky local festival you’d find in any White urban neighborhood somewhere along the anarchist-co-op to million-dollar-condo gentrification spectrum. It was a twenty-four hour bike race, because of course it was. You are allowed to roll your eyes. You are allowed to write it off as just one more self-congratulatory exercise on the part of the kind of White people who have opinions about hazy IPAs and mid-century-design and Sally Rooney novels. You are allowed to mutter something about how all White things merge into one and eventually flow into Burning Man. That’s fine.

And yet!

At 3:00 AM on Saturday morning, I woke up and left my house for a volunteer score-keeping shift. I walked past dozens of yard signs reminding motorists, cyclists and pedestrians alike to not be jerks. I passed by a couple intersections that, even at that early morning hour, were staffed by pool-noodle-wielding traffic captains. The streets weren’t closed off, because that has never been the point of this particular event. The goal wasn’t to create an artificial utopia where we can have nice things because of temporary top-down decree. It was to remind myself and my neighbors that we can create nice things for and with each other whenever we want.

For the next four hours, I did my best to live up to the challenge. I punched laminated manifests to help riders track how many laps around our neighborhood they had completed. I reminded hot shots to chill out, because it wasn’t really a race. I tried my best to answer questions about various community-centric bonus challenges— Narcan trainings and sunrise dance parties and breakfast buffets at interracial churches. I danced to the Miami Vice theme because one of the other volunteers thought we’d enjoy it.2 I drank a Topo Chico hard seltzer because an entirely different volunteer thought I’d enjoy one of those as well.3 I hugged a fair number of old friends and met a bunch of neighbors who were strangers to me hours before. At some point, the sun rose and it was beautiful.

A few hours later, after a short nap, my wife and I took our son and daughter to the kids’ race, where adult riders were asked to pause their own laps around the neighborhood to cheer and blow bubbles and to afix hundreds of temporary tattoos on wiggly arms. There were free popsicles. There were giggles. There was adult-sanctioned-opportunities-for-children-to-use-spaypaint-canisters.

And then, there was a family lap around the four-mile-long main course, where now, in the middle of the day, we could take full advantage of the front-yard-house-parties that had cropped up along the route. We were offered free pancakes. We were offered lemonade. We were offered so much food and so many beverages. One family was giving out Dixie cups full of gummy bears. I’ve never had a Dixie cup full of gummy bears! Pretty good! And then, rather than going home, all four of us decided to set up camp at a busy intersection and spend the final hour directing traffic ourselves.

It was all incredibly lovely. And fun. And no, it did not change the world and yes, perhaps there is something like this in your community, something that is perhaps a bit too White and perhaps a bit too much a harbinger of gentrification but that is creative and neighborly and communal and asks you to be something more than a consumer-of-lifestyle-affirming-products and/or a passive retweeter of outrage.

Or at least I hope there is.

I hope so because things like this (which, by the way, is called the Riverwest 24) are at once simple and profound. Because they exist without corporate sponsorship or philanthropic patronage, they require practical, participatory effort on the part of a whole bunch of neighbors. Because they are slightly-utopic, though, they also spark the imagination of everybody involved. What if I was this happy all the time? What if I knew more of our neighbors? What if we cared more consistently about delighting children and keeping them safe? What if people offered me food and drinks, no questions asked? What if I did the same? What if we put on a big fun race for the hipster bikers but we didn’t close down the roads because it’s important for all of us to remember that our city’s buses take people to work and we shouldn’t mess with that?

I love this single silly little neighborhood bike festival because it wasn’t invented in a reactive huff. It came about over a decade ago because a bunch of neighbors thought it would be a nice thing to create. It continues to exist because they were correct.

Here’s another story.

A century-and-a-half-ago, a bunch of farmers were getting a raw deal. That in itself isn’t news. American agriculture is always, to varying (and intensely racialized) ways, the story of somebody getting a raw deal. In this particular case, farmers— White and Black alike- were being squeezed because the government was more interested in protecting the bottom lines of banks and railroads than a nation of modest soil-tillers. You are, I’m sure, at least passingly familiar with this story- it’s primarily about monetary policy and the gold standard and there’s about an 80% chance that it constituted a good percentage of the part of your high school history class that put you to sleep. You probably forgot about the crop-lien system (I did), but rest assured it was bad too. It made a lot of folks very poor. And though farmers knew they were getting ripped off, there wasn’t a lot of hope that they could do anything about— their plight wasn’t the concern of either of the two major political parties, but Post-Civil-War sectional loyalties meant that poor farmers on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line couldn’t imagine themselves being anything but Democrats or Republicans.

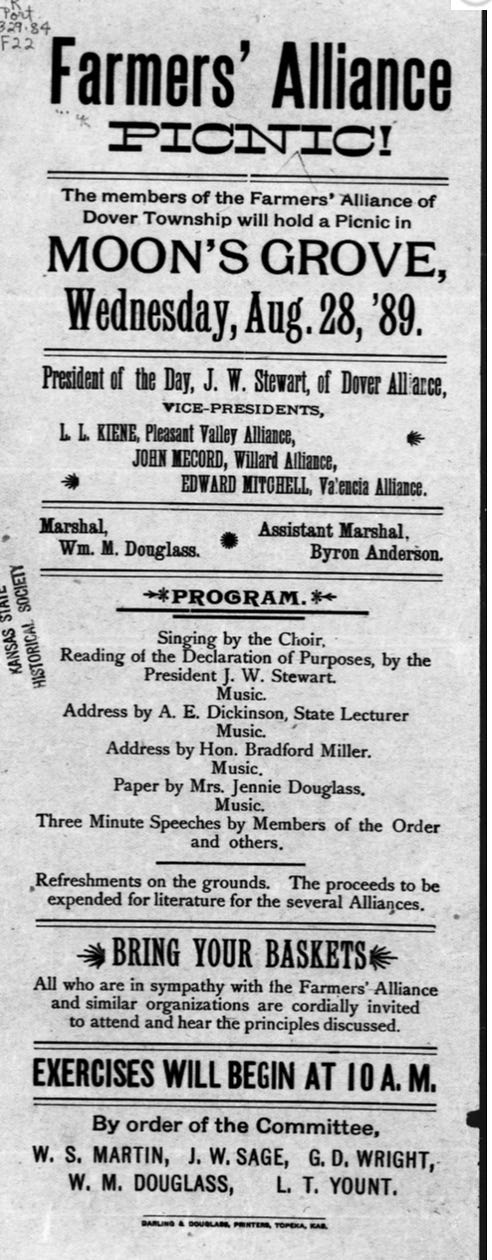

And then, all of a sudden, farmers across the country did start imagining themselves differently. In the 1880s and 1890s organizations called Farmers Alliances’ sprouted up in old Union and old Confederate states alike. Over time, they evolved into a wild combination of political education hubs/economic cooperatives/radical political parties. Thanks to “Traveling Lecturers” (barnstorming organizers) like S.O. Daws and William Lamb, membership spread like prairie fire- at one point, the Alliances counted over two million members in 43 states. As their ranks swelled, so too did their political imagination— Alliances became spaces where the most Quixotic political ideals took hold— concepts like women’s political leadership, working class solidarity between urban and rural Northern White ethnic groups and (most surprisingly, perhaps) interracial White-Black organizing in the South.

These radical dreams weren’t instantly shared by all Alliance members, but as farmers become more and more involved, they started viewing both themselves and the world around them differently. In his landmark works on the Alliance4, Lawrence Goodwyn talks about the birth of a “movement culture,” where farmers who had internalized the idea that they were powerless hayseeds discovered their collective potential. As Goodwyn notes, the process by which this political transubstantiation took place wasn’t intellectual, but came from the clear, physical experience of being together in a visionary mass movement space.

How is a democratic culture created? Apparently in such prosaic, powerful ways. When a farm family’s wagon crested a hill en route to a Fourth of July “Alliance Day” encampment and the occupants looked back to see thousands of other families trailed out behind them in wagon trains, the thought that “the Alliance is the people and the people are together” took on transforming possibilities. Such a moment- and the Alliance experience was to yield hundreds of them- instilled hope in hundreds of thousands of people who had been without it.

There is a cynical way to tell the Alliance story, of course. They didn’t end up leading a mass working class revolution. The closest they came was the nomination of William Jennings Bryan to the Presidency, but big business and big politics had the last laugh there. As for building an integrated, interracial movement, one that could wrest the White Southern working class away from Lost Cause nostalgia? We know how that panned out as well.5

As Goodwyn argues, though, social movements that directly confront America’s most stubborn sins shouldn't be judged as failures for not single-handedly slaying them in one fell swoop. All it takes is a quick glance at the major Alliance demands— a graduated income tax, the eight-hour workday, direct election of senators, citizen referendums and regulation of agriculture markets- to see that their longitudinal batting average actually places them among the most successful social movements in American history. Not bad for a bunch of uneducated farmers on the then-edges of of the American republic.

The Alliance story, of course, isn’t unique. It’s literally the story of how social change happens. One day, a bunch of farmers in the Texas Hill Country, fed up that the world they knew instinctively that they deserved didn’t exist, tried their hand at building a different world. They didn’t wait for a favorable news cycle or a clear sign from God. They just made it up. And then, in the process of making it up, they became wiser and more caring and more visionary and more confident.

Change a few details and here and there and that’s the story of farm workers in Delano, California who brought the world’s eyes to the grape fields. It’s the story of a couple community college students in Oakland who, in a few short years, transformed Black America’s entire sense of their collective power and beauty. It’s the story of Queer New Yorkers in the 1980s, a community whose invisibility at the hands of an uncaring government was killing their friends and lovers en masse, discovering how to make themselves impossible to ignore. It’s the story of teens and twenty-somethings in the 2020s wondering “why isn’t anybody acting as if the climate crisis is an urgent emergency” and then deciding that it might as well be them.

It’s the story of just creating the damn thing.

It’s the story of not holding out for some imaginary moment when you’re smarter or braver or less tired.

It’s the story of not waiting for your hand to be forced by this or that tragedy or this or that authoritarian overstep.

It’s not the story we’re used to writing, those of us who live in a world of reactive news cycles, where our over-broken hearts have been trained to ping pong between tragedies. Here, we say without thinking… take our aching heart, Black Americans being killed by the police! Now you take it, children shot dead at school! Your turn, Ukranians! Now you, climate refugees, please appreciate the earnestness of our empathy, at least for now, in the summer, when we’re thinking about you because we ourselves feel temporarily hot.

As I write this, Americans who dream of collective care are celebrating a rare victory. This week Kansans voted, in droves it appears, for reproductive justice. Ad astra per aspera, indeed! And yes, for many of us, this was a morsel of good news. That doesn't make it any less reactive, though. Remember, it was well-organized anti-abortion activists who first initiated the Kansas referendum. Even this piece of good news didn’t come about because we imagined it into being. We were reacting. And we may have reacted well, but we were still reacting. Let us celebrate, but don’t mistake good news for the building of new, different muscles.

This thing that too often passes for political engagement in to many of our lives— reading the news, paying attention to what’s trending on this or that social network— doesn’t do much of anything to jumpstart our political imagination. It doesn't make us look at ourselves or our neighbors in a new light. It can spark our empathy, I suppose, but more often than not it mostly makes us anxious and jittery.

I don’t, of course, believe that we should all go out and reinvent a million wheels. I am a White guy who has attended one-too-many social entrepreneurship workshops. Goodness knows that I’ve seen the dangers inherent in folks who are used to having their voices affirmed crowning themselves America’s Next Great Movement Leaders. One of the most important topics we cover in Barnraisers training cohorts is how to analyze a landscape and make whatever you’re doing or launching accountable to communities other than your own.

What I’m saying is, it’s worth paying attention not to whatever this or that screen or this or that quasi-political media influencer is telling you to react to on any given day, but what you actually wish was true in your community. Perhaps you live in a neighborhood that only cares about your own property values and not their impact on all your neighbors! Perhaps you live in a county where everybody drives a car because the transit schedules have been cut to shreds and all the bus stops are in litter-strewn ditches! Perhaps you live in a state with a reactionary state legislature and you would instead like a representative body that actually cares about human beings! Whatever it is, it is worth asking around, “is anybody working on this? Is anybody dreaming of something better?”

If somebody’s already working on it, it’s worth joining them.

If a group of somebodies who you’d think should be working on it aren’t, it’s worth asking (politely and humbly), why not and whether they’d like to.

If nobody’s already working on it, it’s worth inviting some folks to your backyard or synagogue or favorite bar or wherever will have you and asking “hey, what if the people we’ve been waiting for were… us?”

And if you do any of that and want help or commiseration or somebody to cheer you on, let me know. I’d love to be that person. I have a feeling I’m not the only one.

END NOTES:

This week’s song: “Something’s Burning” by Seam

(please Gen-Z, rediscover Seam the way you recently rediscovered Kate Bush! You won’t be disappointed. Vibes! I promise!).

My favorite recent “subscriber’s only” discussion: Last week, I asked “what about your current life would make five-years-ago-you proud” and holy cow. Thanks everybody, both to those of you who felt like they were in a great place compared to five-years-ago (we had divorces and recoveries and financial independence and really good hikes) and to those of you for whom the last five-years have been awful but you’re still here, still standing. I am so grateful to get to know all of you a bit more every week.

[Full disclosure: this week’s discussion hasn’t yet connected with folks quite as much (it’s about people who influenced our life but don’t know it). Maybe folks are intimidated by my tangent about my favorite David Letterman musical performance of all time (it was Robyn). But I love those slow burn threads too, where I get to spend a lot of time on a few good stories. So thanks for that too, subscriber friends].

In the meantime, if you ever want to join us in subscriber land, you’re always welcome. If you’re in a position to join financially, it’s appreciated. If money’s tight (and/or if you’ve already given to Barnraisers or are a cohort alum), just toss me an email: garrett@barnraisersproject.org.

I mean, I guess we’re always experiencing One Of Those Summers, because that’s what you get with climate change + the Do The Right Thing effect (hot temperatures bringing nascent tensions to a boil), but that’s beside the point. This summer’s been more Supreme Court-y than most, I suppose, so that’s different.

He was right! It holds up.

He was less right. It was fine, but I wanted it to be way fizzier, because that’s what’s great about plain old not hard Topo Chico.

The Populist Moment and The Democratic Promise, the former of which is an abridged and widely available version of the hard-to-find and very long latter. You can guess which one I’ve read.

Goodwyn’s discussion of the failings of the Alliance’s interracial vision are incredible. While the short answer is that the movement couldn’t cleanse its own white supremacy (William Jennings Bryan’s own Vice Presidential candidate, Thomas E. Watson, would himself devolve from an integrationist youth to a virulently racist old man), that’s only one layer at play. On the Black farmers’ parts, there was a careful political calculus of how safe it was or wasn’t to align with a bunch of White radicals (a calculus that, of course, their White would-be partners neither understood or appreciated). What I’m saying is sometimes the lessons of the past for our current context aren’t all that opaque.

There's a great piece out this week on Scalawag that tells the story of two farmers in Mississippi who are trying to keep alive that tradition of the old farmer coops https://scalawagmagazine.org/2022/08/black-farms-in-mississippi/

"You are allowed to mutter something about how all White things merge into one and eventually flow into Burning Man." Hilarious line that I didn't know I needed to explain Many Things!

What a fantastic post. Last week I was in a totally different town and ran into someone I'm on a bike/pedestrian committee with and he's now running for office, and we talked a bit about how people think a little bike/ped committee is low-key and, I dunno, just does bike to school days, but in reality it's filled with the tension of participatory democracy and you learn *so much* about how to get things done and also how things fail just by being involved with something like that.