You won't save the world by blowing a hole in the sky

Happy Ruination Day! Let us love each other even harder.

I don’t normally publish essays on Sunday, but I always publish an essay on April 14th, so here we are.

If you’re new here, there’s less back story to this little ritual than you might think. In 2001, the folk singer Gillian Welch released an album called Time (The Revelator). Hell of an album. Holds up like a Douglas Fir. But for the purposes of this essay, what matters is that the album contains two songs about a single date: April 14th. Today! Ruination Day!

Ruination Day exists because Gillian Welch noticed a weird cosmic coincidence and then wrote a song about it. Basically, a whole lot of Grandly Tragic Historic Events all took place on April 14th. Lincoln was shot. The Titanic sank. And the single worst day of the Dust Bowl ravaged the Great Plains. Throw in the fact that, on any given April 14th, most of us are probably navigating one of life’s many smaller tragedies (in one of her two Ruination Day songs, Welch recalls the plight of a broke, unloved Idaho punk band she saw outside a rock club one April 14th), and, well, you’ve got a real conversation piece.

That’s all you really need to know.

Why am I so fascinated by Ruination Day that, for the third year in a row, I actually commemorate it? Like, as a real holiday, with its own set of rituals (truth be told, I mostly just publish an essay, but still, that’s not nothing)?

Every year, I answer that question in a slightly new way, but it doesn’t really need an answer. Just a few days ago we all stared at a disappearing sun and cheered as the world around us turned dark and cold for a second and then let out a second cheer as warmth and light returned again. There is something comforting in how little we understand the world. It is a gift to be fascinated, whatever the source.

In past years, I’ve talked about the sin-eater aspect of the holiday, about how of course I don’t actually believe that a single day is able to voluntarily gobble up an outsized percentage of devastation, leaving 364 other days free from harm. I know why we wish that was the case. Or at least I know why I wish that was the case. I want less harm in the world, and if my first wish (that none of us were ever hurt) is impossible, then I suppose I’d settle for the consolation prize of balling up all the pain in the world into as small as possible a vessel that it might be tossed away.

The moral of Ruination Day is that, seemingly cosmic coincidence aside, none of April 14th’s core tragedies were accidental. The Titanic sank due to corporate greed and excess. Lincoln was murdered (setting off a chain of events that would scuttle the hope of Reconstruction), because of organized White supremacy. The Great Plains turned to dust because Manifest Destiny was a bloody, ecological and humanity destroying disaster.

This year I’m thinking less about who is to blame for the tragedies that envelop our world, not because it isn’t necessary to identify and confront villainous root causes, but because that feels like only one part of the equation.

The dust bowl didn’t begin on April 14th, 1935. Depending on what part of the Great Plains you lived in, the dust had been swirling for months. But more accurately, it began as soon as the Homestead Act became law and the prairie grass was dug up and herds of White people and cattle streamed onto places that were now declared to be America. But there’s something in us as human beings— maybe grit, maybe stubbornness, maybe hope, maybe stupidity— that makes us believe that we can stave off true disaster if we just make a loud enough noise.

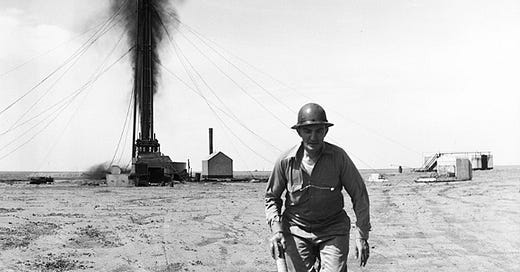

And so a few days before what had become known as Black Sunday, Tex Thornton, an oil field explosives expert from Amarillo, traveled out to Dalhart, out on the Panhandle. Maybe it was just a bad drought, Tex hoped. Maybe a good cleansing rain would hold off Armageddon. And so, with a crowd of on-lookers gathered round, Thornton fired blast after blast into the sky. If God won’t answer a community’s prayers then, in the White West at least, the prayerful must go to war with the heavens, daring God with torpedo after torpedo.

Relent. Send the rain, goddamnit. Or else.

The rain didn’t come. Of course it didn’t. “No flood… the dust this time.”

Ironically April 14th, 1935 began as an idyllic spring day in many parts of the Southern Great Plains. Sunny, blue skies, mild temperatures. The skies to the north turned more foreboding around noontime, and by early afternoon all hell had broken loose. One eyewitness, Pauline Winkler Gray from Meade Kansas, described the terror of a suddenly bifurcated sky.

"It was as though the sky was divided into two opposite worlds. On the south, there was blue sky, golden sunlight and tranquility; on the north, there was a menacing curtain of boiling black dust that appeared to reach a thousand feet or more in the air."

As the dust swirled and the sun disappeared, this time with no guarantee that it would ever return, talk turned to the end of the world.

It wasn’t the end of the world. It rarely is. But that only made the situation at hand more complicated. After the storms died down and the dead were mourned, the survivors were left with a world that had not ended, but with the terrifying knowledge that violence, noise and the sheer force of will hadn’t kept them safe. All that was left was care. Neighbors had to offer each other shelter. Children had to be comforted. Migrants’ cars had to be packed up for the trip to California. And far away, in seats of power, laws had to be passed (like the Soil Conversation Act) in the hope that a lesson might have been learned.

This Ruination Day, I’m thinking about Tex Thornton firing explosives at God, hoping the force of his opposition might save his community. And I’m thinking about Pauline Winkler Gray and her neighbors, staring at a sky split between perfection and devastation, imagining that maybe life would remain the same if only they stayed on the blessed sign of the line.

There’s a movie in theaters right now called Civil War. It’s telling that advance conversations about the film haven’t been about whether it’s realistic to imagine another Civil War in America, but instead something closer to “wait a second, the separatists in the movie are based in Texas AND California? That would never happen.” In the current national imagination, the only reason we haven’t had a civil war is that we’re too divided even to muster the energy to coordinate it.

We all have our own version of future disasters that we’re obsessed with staving off: Another war. The end of democracy. A world on fire. And there are plenty of ways in which those fears can animate useful, necessary community action. Fear doesn’t always leave us dynamiting the sky.

But there is so much that we lose in obsessing over future disasters, particularly those of us who are cocooned from the worst excesses of our current violent world. We all know, intellectually if not experientially, that all the worst of our fears are already true. I am not living in a war zone, but I just filed taxes and, in doing so, tethered myself to bombs dropping on children. Most (but not all) of my neighbors can still vote in political elections (for candidates that represent them well? perhaps not!), but in a country where union membership is (still) at a nadir, few of us experience any meaningful form of democracy in our workplaces. And of course, the world is already on fire. Today the air in the place I live is breathable, but there’s no guarantee it will be tomorrow.

We know this, which is why it’s so easy to slip into pedantic fatalism, the kind that animates the most nihilistic left-leaning spaces. “Everything sucks, Amerikkka is fascist, people are terrible…” and all that. Like, subscribe and follow for breaking news on how everybody you hate is even more hatable than you even imagined.

There is a gift, however, in recognizing that the dust is already swirling around us. It means that we don’t have to wait to care for one another. Whatever you would do for your neighbor, for your community, in services of preventing a repition of tragedy is useful and good and necessary right now.

The world is already broken in pieces. And while we don’t bear the brunt of that brokenness equally, none of us live fully outside of it. So who are we for each other when the storm is raging and the boat is sinking and the assassin’s bullet has left the chamber?

The wonderful thing about dutifully commemorating a made-up holiday is that you don’t get bent out of shape with the knowledge that you’re likely celebrating alone. I assume that Gillian Welch feels some degree of affection for this day that she imagined into being, but who knows. She’s written a lot of songs.

All I know is that I love this holiday with all my heart. I actually look forward to April 14th every year. I always tell myself, a few days before, “you don’t have to write the essay again” and then I do.

I love having an annual reminder that I only have direct relationships with a fraction of the human beings with whom I share all this world, but I want all of us to come out of this moment safe and loved. I want that regardless of who is more or less culpable for causing harm. I want that even for somebody who wishes harm on me.

I want it so deeply, in fact that, once a year, I engage in this annual ritual of irrationality and rationality staring each other in the eye: Imagining with all my heart that on April 15th the harm will disappear, knowing full well that dream will not come true, being grateful that the work of care and love remains.

So Happy Ruination Day. Again. May the world we share next year on April 14th be more gentle and enveloped in love than the one we live in today, not because we were spared by luck or coincidence, not because we scared God or our enemies into submission, but because of all the work we did for one another.

End notes:

I wrote a book about caring more about loving you all and less about trying to be right. Many of you have purchased it and shared it and come to events and said nice things about it both to me directly and in the places where people review books and jeez that means so much. For those of you who haven’t bought a copy yet, please consider doing so. I think you’ll enjoy it.

One thing not covered in the book: How to actually do the work of organizing. Why? Because that’s more fun to share in trainings and conversation than in a book. Which is where the Barnraisers Project spring mini-sessions come in. Two hour, standalone sessions. You only need to come to one, but the first class is coming up on Friday (and registration will close 48 hours before the session), so hop on it!

And also: If you’re in or around Omaha, Nebraska this coming Wednesday (the 17th) come hang out with me and New York Times bestseller

. Pageturners Lounge. 5:30 PM. Fun, fun, fun. I am driving there from Milwaukee and as was the case with my book event in La Crosse, WI last week, by the time I get into town I’m going to be so filled to the brim with Kwik Trip coffee I swear to God.Can’t make it to Omaha? Well, on Friday the brilliant

and I are having a Zoom party to talk about the book and you’re invited. Friday the 19th, 10:30 AM PT/1:30 PM ET. Sign up here. Who’s to say how much gas station coffee I’ll have drank before that one (probably not much, since I will be in my bedroom, but you never know).Phew! I think that’s all the logistics. Let’s do the song of the week! As is true every year, there’s only one choice (well, two choices, but you get it). Thanks Gillian, for inventing my favorite holiday and also for the way you sing the lines “They looked sick and stoned/And strangely dressed/No one showed/From the local press.”

A beautiful, compelling case for action. Thank you. Taking this quote to heart today - a picturesque blue sky Sunday in Baltimore:

“There is a gift, however, in recognizing that the dust is already swirling around us. It means that we don't have to wait to care for one another.”

Reminds me of piece of advice overheard at a party last night, “start before you’re ready”.

Happy Ruination Day!

Happy Ruination Day Bucks! I loved this meditation on apocalypse and other motivations and do every year. As my friend Nguhi recently said, “if we’re in the ‘bad place,’ ala The Good Place, we might as well be inspired to make art and show up for one another.”