"You’re the elite… you’re smarter, you’re better looking, you have a better future"

On the stories that white supremacy tells and the danger of not having a response

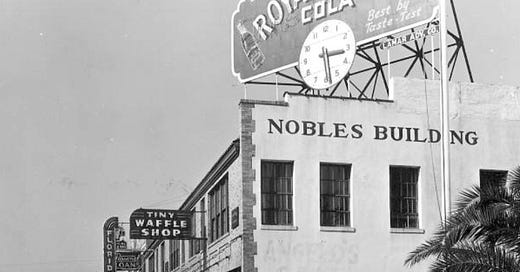

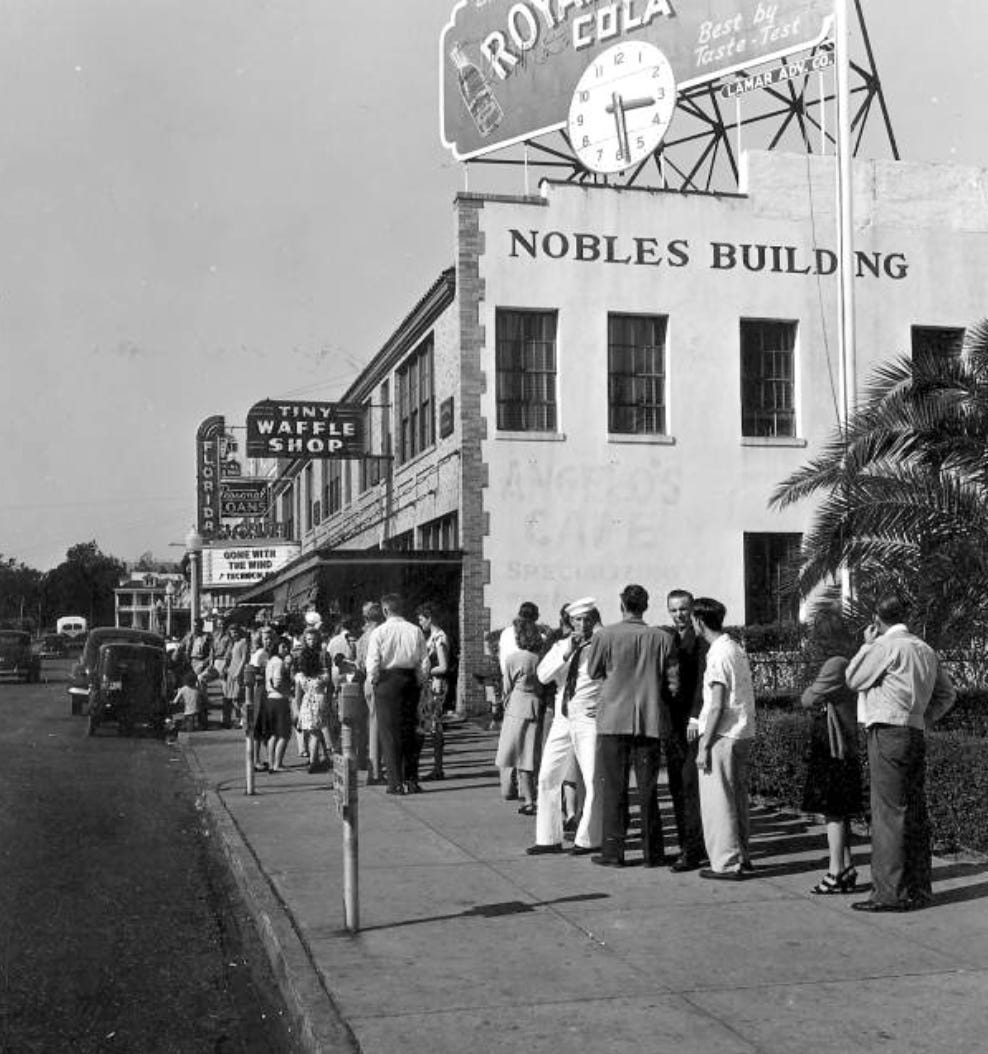

Crowds lined up to see Gone With The Wind in Pensacola, FL, 1947 (Public Domain)

Note: This week’s issue is dedicated to the proud legacy of Black activism in Tulsa. While I ended up deciding to focus on a different incendiary Trump speech rather than the one he gave in that city, Tulsa has been in the news quite a bit this past week. Too often, when we talk about race in Tulsa we talk about Black victimhood- about the horrid legacy of the Black Wall Street Massacre. While that’s hugely necessary, we should also be celebrating Black leadership in that city. If you have a chance, I’d encourage you to read this article, check out the great work the MetCares Foundation is doing and, if you’re inclined towards electoral politics, support Greg Robinson’s inspiring mayoral campaign. Tulsa’s one of my absolute favorite places in the world, not because of its legacy of oppression but because it is filled with people imagining a new way forward.

The President of the United States is holding rallies again. There was the famously empty one last week in Tulsa and then a youth-focused affair in Phoenix a couple days ago. The Phoenix event took place in a megachurch that boasted that one of its parishioners had invented a magic Covid-killing air filtration system. "Ioniz-ition (sic) of the air…” the pastors said, convincingly, in their announcement video, “…Covid can not live in that environment.”

“Thank God for being proactive!” they added cheerfully.

The claims were later walked back.

I haven’t watched many full Trump rallies. I’ve experienced most of them the same way the rest of left-leaning America has, like a glacial IV drip of social media content spaced out over five years. Clips of the President saying abhorrent things. Clips of the President sounding dumb. Live fact checks revealing that the President was lying. “Yesterday, at a rally in Tampa, Donald Trump claimed that former President Obama held daily ceremonies on the West Lawn where he allowed undocumented immigrants to shoot paint balls at Gold Star Families. We rate this claim as ‘mostly false.’” Drip. Drip. Drip.

I decided to watch the entire Phoenix rally. I’m still not quite sure why. I guess I was getting nervous about premature declarations of victory, about celebrating at the 50 yard line and whatnot. There had been a couple days straight of collective left-liberal schaudenfraude over empty rally seats and dismantled overflow stages and ticket-hoarding Tik Tok teens. And that felt good, of course, but the fact remained: this is still a country where millions of people would like to have their President reassure them that Black Lives Matter is a terrorist organization and that the only people who distrust the police are vile authoritarians.

Truth be told, I multi-tasked as I watched the rally. I checked in on it while reading Nikole Hannah-Jones’ new case for reparations in the New York Times. It’s an incredible, far-reaching piece and it covers a lot of history, all of it compelling. It is, as always, the Reconstruction story that stops you in your tracks. It’s the sliding door moment of American history, this deeply imperfect but tantalizingly promising period where it looked like Black freedom was at least being considered as a serious possibility. It is this now-surreal moment when 2000 Black men were elected to public office, when Black businesses and community institutions bloomed and where 40 acres and a mule was an actual promise and not a cruel punchline.

That moment disappeared, of course, because enough angry white people, including more than enough extremely powerful white people, couldn’t stand for restorative justice, couldn’t abide by anything good being done for Black people specifically. As white Americans, there is no more consistent historical through-line than our tendency to throw violent, destructive toddler-fits whenever Black people start getting even a few nice things.

I watched the Trump rally because I still hold out hope that “this moment might be different,” that the consciousness and care we’re seeing from increasing numbers of white people might be more sustainable than it has been in the past. But naive, unchecked hope doesn’t help anybody. And while any chance of a New Reconstruction will be just as likely to be booby-trapped by nice white liberals as it will by MAGA crowds, it still felt foolhardy to not at least check in on the Andrew Johnson campaign rallies happening in our midst.

I watched because, to borrow a phrase from Anne Braden, I wanted to know who was more likely to effectively organize a nation of white people— “the freedom movement” or the forces of entropy and hate.

Grace McKinley walking her daughter, Linda Gail to Fehr Elementary School, Nashville, 1957 (Nashville Public Library)

For those of you who have only seen clips from Trump rallies in passing, here are a few things you should know about them:

They are not good speeches, either rhetorically or morally. You knew that already. They are as rambling and tangential and as full of explicit and implicit racism as you’d expect. In Phoenix, he and his supporters did that “joke” where they dare each other to say the most racist name possible for the Covid virus. It isn’t a good joke.

They are, however, deeply effective speeches. Just devastatingly so. Are you familiar with Marshall Ganz’s “Public Narrative” framework? The basic idea is, if you want to inspire a group you’re organizing, you use a three-part rhetorical strategy. First comes a “Story of Self” (so that your audience feels connected to you), then a “Story of Us” (which then moves the narrative from a “you” story to a collective “we” story) and finally a “Story of Now” (where you lay out why specific collective action in this moment is so important). While a Trump speech would be more accurately diagrammed as Highly Aggrieved “Story of Us”/Tangential and Even More Aggrieved “Story of Self”/Beginning of “Story of Now” Quickly Abandoned For a Different “Story of Us”/Unnecessary and Incomprehensible “Story About the Theoretical Defacing of Winston Churchill and Gandhi Statues,” the overall impact still lands.

A Trump speech is actually a symbiosis of two speeches colliding into one another at random angles. There is the speech on his teleprompter, which is a pretty standard issue “us vs. them” Stephen Miller-penned bromide against the sinister left-wing menace. This one is necessary because it provides a narrative through-line. The problem is, it actively bores both Trump and the audience (the only moderately enjoyable aspect of watching a full Trump rally is seeing him react to the prompter with the exact same put-upon dejection that my three-year-old displays when she has to clean up her Magna-tiles). That’s why you need Trump’s frequent interjections, those moments when he really gets cooking. These also have a very obvious downside in isolation: they make very little narrative sense and are disproportionately focused on petty personal beef. When attached to more boiler-plate authoritarian storytelling, though, Trump’s Dangerfieldian “I don’t get no respect” routine makes him a deeply resonant stand-in for his audience’s own feeling of being at siege from a hostile culture and media.

With that context in mind, here are a few quotes from Trump’s Phoenix rally.

“Our country didn’t grow great with them-- it grew great with you and your thought process and your ideology.”

“The left is not trying to promote justice or equality or lift up the downtrodden-- they have one goal, the pursuit of power- that’s their one goal, their goal or their sickness.”

“We believe that the beloved heroes of American history should not be torn down by militant mobs but held up as an example to the world-- now they’re after George Washington, I said what did he do wrong?… Thomas Jefferson-- we stopped them, they were heading towards the Jefferson memorial, they couldn’t care less, I think half of them don’t even know who Thomas Jefferson is. How about Ulysses S. Grant? They want the confederate soldiers, but he’s the one that defeated the Confederate soldiers, so what’s that all about? How about Gan-dhi? How about Churchill?.... we’ll stop it don’t worry, just don’t worry about it…. Ten years is a long time to spend in prison.”

“Our people are stronger and our people are smarter… we are the elite… they’re not the elite… you’re the elite… you’re smarter, you’re better looking, you have a better future, you know your way around better, believe it or not… there’s only one thing they have… they’re more vicious… anyone who dissents from their orthodoxy must be punished, cancelled or banished… but you must not be silent”

“So we’re not going to take moral lectures from the same left wing ideologues who oppose school choice, who support deadly sanctuary cities, who want to defend our police to fund and abolish our police….The murder rate in Detroit and Baltimore is higher than that of El Salvador, Guatemala, or Afghanistan….Think of that, tougher than Afghanistan, all run by Democrats while their movement is based on hate. Ours is based on love. Love of our family. Love of our nation and love of our fellow citizens. We embrace the noble vision of Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.”

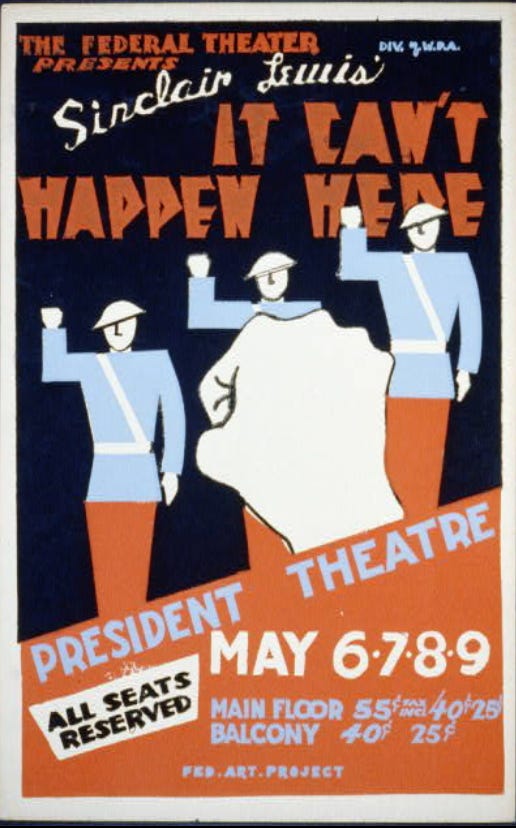

Poster courtesy of Library of Congress (WPA poster collection). Oh, and spoiler alert… it can happen here!

Social psychologists are fascinated by cognitive dissonance- the moments when the human mind has to reconcile the story it has been telling itself and evidence of a conflicting reality (a hat tip is owed here in particular to the work of Carol Tavris and Eliot Aronson). For the last decade (and increasingly in the last month) white Americans have been asked more actively than at any other point in my lifetime to confront a particularly knotty form of cognitive dissonance— the reality of our complicity with American racism juxtaposed against our perception of ourselves as decent, moral human-beings.

In response to this dilemma, all of us white people basically make one of two sets of choices. Either we attempt to reconcile that cognitive dissonance by changing our worldview and actions (through attempts at anti-racist thought and practice) or we reject the call to do so, blaming the moment of cognitive dissonance on the messenger and doubling down on stories of our own righteousness. This isn’t a single static choice— all of us walk the righteous path until we reach the point where we personally feel too challenged or uncomfortable and then we turn around. While each of our “turning around points” are different (for some “not supporting Donald Trump” is the step too far, for others its “quitting my job at _____ nonprofit or ________ corporation that is contributing to structural racism” or “refusing to call the cops” or “sending my kid to an open-enrollment, non-magnet, predominately Black and Brown school”), the overall psychology remains the same.

In either case, the work of anti-racism organizing is to try to get white people who have all sorts of stopping points to keep walking forwards. The work of white supremacy, by contrast, is to soothe and reassure, to tell white people that they’re OK where they are, that no further action is necessary.

It is tricky to talk about persuasion, about winning hearts and minds, when you’re a white person doing racial justice work. It is understandably insulting and painful for many Black and Brown and Asian and Indigenous people to have their humanity presented as something that might necessitate a strategic appeal. And yet, if we care about changing the patterns of history, it would behoove us white people to be obsessed with how we motivate both ourselves and other white people to keep moving, to not turn back, to resist the siren song of inaction.

And so, it is worth asking: who will win the battle for white hearts and minds, including our own? And quite frankly, I’m worried. The pitch I heard in that Phoenix rally is a powerful anesthetic for this moment of cognitive dissonance. It acknowledges the reality of the moment but numbs it. It says, essentially, that “you, the angry white person, are doing everything right… you love and care for everybody, you believe in national unity. It is the ‘anti-racists’ that are wrong, it is they who are divisive, who don’t understand the message of MLK. People are only telling you that you’re wrong because they have hate in their hearts.”

I worry because not only is that an extremely seductive pitch, but it is a message that codifies individually scared white people into a reactionary white community. It is not just you as an single person who are on the right side of history, but all the other self-identified patriots gathered together in sports arenas and spuriously Covid-free megachurches: “Our country didn’t grow great with them-- it grew great with you and your thought process and your ideology”

It is the exact story that has mobilized previous generation of white Americans to roll back and undo every single one of our country’s tentative steps towards justice.

In response, those of us who are white and purport to care about anti-racism don’t really have a story to tell about who we are as a collective or what’s on the other side of this cognitive dissonance. Our actions and rhetoric are disproportionally focused on individual acts of guilt appeasement and purification. Literally as I was writing this the [No Longer Dixie] Chicks put out a protest song that attempts to respond to our current moment with a chorus that proclaims “March March To My Own Drum. Hey Hey, I’m an Army of One.” We jostle for position with one another, collapsing anti-racism into the same individualistic package that got us into this mess in the first place.

We act with the hope that if we read enough books, read and adopt more impeccably radical political stances and make more (oh jeez, really?) unsolicited cash donations to Black co-workers, we are “doing the work.” But what’s on the other side of that work? And why do we want others to join us, other than that we believe we are right and they are wrong? Do we actually want to build a mass movement for white people for racial justice or do we just want to position ourselves personally on the correct side of the moral ledger?

Photo by Joe Brusky and MTEA/Flickr (Creative Commons)

I’ve shared some thoughts in previous issues about potential salves for this individualistic, guilt-appeasement approach. I do believe there’s power in deliberately getting over ourselves, in pushing our imagination as to the world we truly desire and about being obsessed with outreach and base-building. But one thing that gives me surprising amounts of hope right now are growing examples of white people trying to do difficult things together, in community. This remarkable Caitlin Dickerson story about white neighbors in the Powderhorn area of Minneapolis attempting to ween themselves from calling the cops (in particular in regards to a nearby tent encampment) is hardly one of unabashed triumph— it is messy and full of naval-gazing and cautious half steps and understandable eye-rolling from Black and Brown neighbors who don’t trust their white neighbors’ stamina to keep up their commitment.

The hope embedded in the story, though, is that because it is a collective and not an individual effort, there is the potential for this moment to not merely be about an individual purity challenge. As the Powderhorn neighbors try to live their values together, they are being confronted with how little our current world enables them to do so. That realization, in turn, has the potential to spur them from this single experiment to a longer term project of co-imagining and co-creating the city all Mineeapolitans deserve, following the lead of their Black and Latinx and Indigenous and Southeast Asian neighbors. And if they do so, there will be invariably be many messy and even painful moments ahead, but goodness if that’s not only a joyful destination but also a decent and kind way to live your life.

And that, in the end, is what white people committed to racial justice have to offer one another. The forces of white supremacy and entropy have a seductive but soul-destroying offer— do nothing and there will always be another demagogue to assure you that you’re in fact on the righteous side. We do have a counter-story though. It’s not an easy one by any means. It’s full of (perceived and real) sacrifice and uncomfortable critique and clumsy missteps. But it is a story that’s so much more beautiful than the one into which we’ve defaulted. What we have to offer isn’t the false promise of guilt appeasement or superiority over other white people. It’s the chance to build a collective life worth living in community with others. It’s to fail a lot, sure, but to build deeper and deeper relationships as we do so.

The flawed and broken world as we know it depends on all of us white people defaulting back into our embrace of power, inaction, violence and individualism. We can’t scold ourselves or others into resisting that gravitational pull. What we can do, though, is start walking forward, extending hands and hearts in multiple directions as we do so.

This week’s song: Woody Guthrie “All You Fascists Bound To Lose”