"I'll Never Be Hungry Again"

10 Movies, 10 Stories of Whiteness Issue Six: Gone With The Wind, The South, and How To Become a White Woman

Top notes (from Garrett)

Welcome new readers! I have been looking forward to this guest post for months. It’s by a writer I love, Sara Beth West (whose bio is down below) and it’s about the film that inspired this whole series. I’m really into this essay for a lot of reasons, most of all for Sara Beth’s ability to hold up a piece of art that has long been a part of her life and to look at it— with the gift of time, perspective and wisdom— from a wide variety of angles. I hope you enjoy it.

It’s a gift to get to publish Sara Beth’s work (and to be able to compensate her for her wisdom and talent). As is the case whenever I have a guest essay1, I’m offering a one-week subscription sale to celebrate. That button down below should do the trick. 20% off. It helps me pay contributors. You get a bunch of fun perks. Good stuff all around.

Oh, and if you’re new here and you’re not sure what this whole “movie series” is about, you can find an explainer here and all of the previous entries here. Should I have considered ways to make this series more in dialogue with the zeitgeist-dominating movies currently in theaters, like perhaps the blockbuster movie about and for women that has significantly better racial politics? Or the movie about Troubled Men who assuredly went to go see Gone With The Wind (because everybody in the 1930s saw Gone With The Wind) and then blew up the world? Maybe! But one thing I can say, this series about movies supports strikes! Now and always! Oh, and you should read

on Barbenheimer.[Content warning: sexual assault]

Gone With the Wind: America's second-favorite book (behind the Bible) and the highest grossing film in history (after adjusting for inflation). Even before its release in 1939, the movie set off protests, drew massive crowds, and inspired Macy's in New York City to devote entire floors of its flagship store to Dixie-themed merchandise. It also took home 8 Academy Awards that year, including Best Picture and Best Actress for Vivien Leigh as the inimitable Scarlett O'Hara.

From the beginning of production, filmmaker David O. Selznick knew that the dashing Rhett Butler must be played by Clark Gable. The public insisted. There could be no other Rhett Butler. But who would play Scarlett? Though every leading lady in the industry wanted the role, Selznick wanted a newcomer. He knew that the role would make someone a star, and he didn’t want the celebrity of a Bette Davis or Talullah Bankhead to outshine the character. Davis and Bankhead were considered, of course, but they were no Scarlett. Selznick and director George Cukor sent three teams of scouts out in search of the face of the film; they scoured community theaters and college campuses, and though they discovered many striking actresses, none were Scarlett.

Selznick issued a worldwide call for the role, and an image was commissioned of the character (posed in the arms of a very Clark-Gable-looking Rhett) for a 1937 issue of Photoplay.

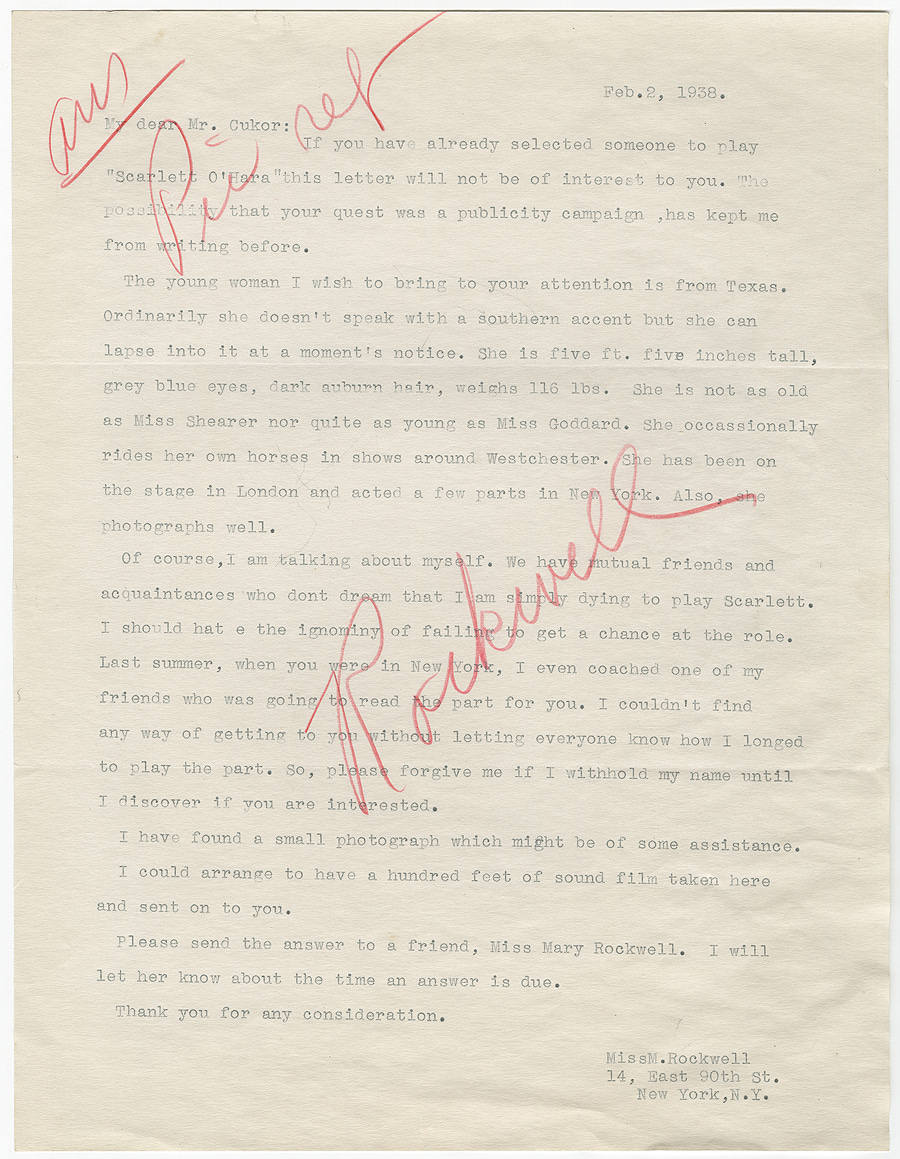

Letters and photographs and spontaneous “auditions” came from all corners. One anecdote describes a Christmas morning when Selznick received a 7-foot tall replica of the book, tied in a ribbon. The ribbon broke, the book opened, and out stepped a woman in a gown, announcing, “I am your Scarlett O’Hara!” Others were more subtle, such as this letter-writer, a seasoned stage actress: “I am simply dying to play Scarlett. I should hate the ignominy of failing to get a chance at the role. … Please forgive me if I withhold my name until I discover if you are interested.”

It wasn’t just actresses who wanted the role. Letters and telegrams poured in from all over the country, from ordinary women who saw in Scarlett something of themselves. They, too, had Scarlett’s hair or eyes or tiny waist. They, too, struggled to hold their tongues or manage their frustrations. As Steve Wilson, curator of the UT Austin Special Collection on “The Making of Gone with the Wind” explained in an interview with NPR, “they identified so closely with this character. … They understood what Scarlett was going through.”

More than 50 years later, I was one of those women.

When I was in high school in the 1990s, one of my nicknames was Scarlett. A group of boys, one of whom I had a ridiculous crush on, gave it to me. My crush sat behind me in Band, and he would whisper, “psst… hey, Scarlett” and pass me notes, and I would toss my head in defiance and pretend to ignore him, and I loved it. I called him insufferable and pretended not to care, but of course delighted in every second of attention.

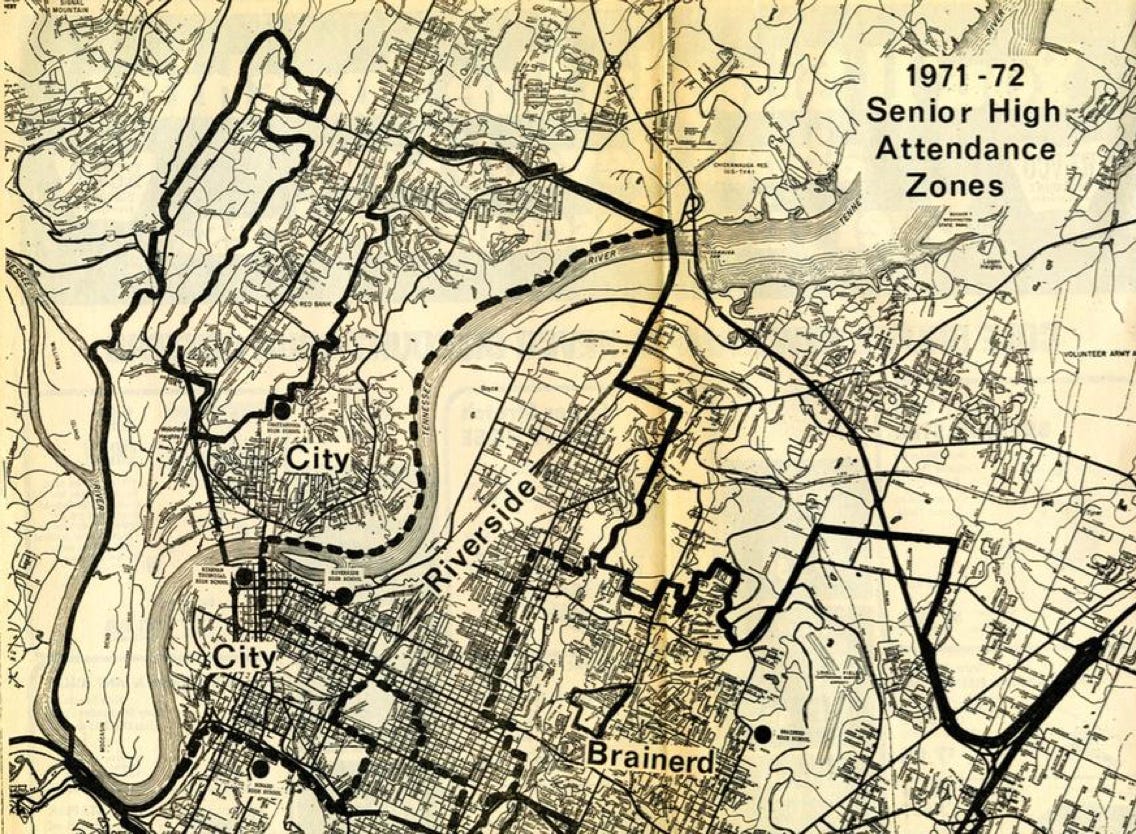

My school was an early example of the magnet or choice programs that cropped up around the South, as an answer to an extremely segregated school system and the failed efforts at forced busing. Growing up in Chattanooga, TN, I was fortunate to attend a school that was intentionally and thoughtfully balanced both racially and economically, a haven of diversity in a city that as recently as 2015 still carried the designation of “hypersegregated.” I ate lunch and went to dances and sat on the bus next to kids of all races, but it was a White boy who called me Scarlett. I had a long list of boys I liked, and they were all White.

As a cishet White girl, growing up in the American South, Gone With the Wind defined both my Whiteness and my Womanhood, two parts of my identity that could not be divorced from one another. Like all those other White women, my model of choice was always Scarlett and never the “pale-faced, mealy-mouthed ninny” that was Melanie Wilkes (née Hamilton).

Countless thinkers have discussed the contrast between these two women, setting them up as two sides of the Southern White Woman coin. Melanie is endlessly kind, selfless, plain, and pure. She is loyal – to her husband, to the South, and to Scarlett. She is meek and quiet and self-effacing, always putting others’ needs before her own. Scarlett, on the other hand, is none of that. Selfish and manipulative, fiercely stubborn and wickedly intelligent, Scarlett is willing to do whatever it takes. She refuses to hold her tongue, refuses to bend to the expectations of society, refuses to be constrained by what others think is right or good.

Also, Scarlett is beautiful. She is the most desirable belle of every ball, the most popular girl at the Wilkes’s picnic, the one men fall over themselves just to eat BBQ with. She is a shameless flirt who knows that her best – her only – real chance at success in this world lies in her body and how she uses it.

In fact, all of the White women of Gone With the Wind know that their beauty and their body is their currency. Every woman at the Wilkes’s picnic knows that her only path to credibility and security is through marriage. And every married woman understands her role in marriage is to be the always-willing but never-desiring sexual partner of her husband and, of course, to produce children. Melanie’s most notable sacrifice, in fact, is when she becomes pregnant against the explicit advice of her doctor and dies as a result. Scarlett knows it, too, and each time that she marries, it is for the financial security and societal stability the institution offers. Her beauty is the only currency she has to invest, and over and over, she turns a profit on her investments.

Like every good investment, there is always risk, and Scarlett knows her beauty is also her greatest threat. When she flirts, she knows she must balance on the knife’s edge of power dynamics and desire, but she also knows she can trust the honorable White men to behave as “gentlemen.” The men she marries are no threat to her, not even the unconventional Rhett Butler. Repeatedly, Scarlett points out Rhett’s status: “Sir, you are no gentleman.” His retort – “And you, miss, are no lady. But don’t think that I hold that against you” – must have thrilled audiences, as they, too, might have wished to throw off the limitations of class and status and respectability and still land the dashing leading man.

But despite all his swagger, Rhett is not to be feared. Even when he openly threatens Scarlett’s life and then rapes her, he is no real danger. Instead, the film cuts from him forcibly carrying her to bed (after her failed attempt to fight him off) to Scarlett in that same bed the next morning, giggling with delight as she recalls the events of the night before. Other than the scene at the picnic, this is the happiest Scarlett appears in the entire movie, and though I missed it as a child, the fact of it is unmistakable now. She is glad that Rhett denied her agency and ignored her lack of consent. She is so very happy because her husband raped her.2

Scarlett, known for her fearlessness, does fear being raped by other men. When she chooses to drive out to the mill alone, Scarlett puts herself in the gravest of dangers. In the movie, she is assaulted by a low-class white man, but those familiar with the book (and that was everyone) would have recalled the book’s version. Mitchell explains Scarlett’s mindset, “Driving alone was hazardous these days and she knew it, more hazardous than ever before, for now the negroes were completely out of hand. … No one was safe from them.”

No one was safe, least of all a beautiful White woman. In the book, there is a “ragged white man” involved in the threat on Scarlett’s safety. But it is the “squat black negro with shoulders and chest like a gorilla” who poses the greater threat. The book makes clear, just as the movie does, that Scarlett is about to be raped, and by the most terrifying of figures: the Black man, with his “rank odor” and “black hand [fumbling] between her breasts.” Scarlett’s greatest asset is her sexuality, and the greatest threat to that sexuality was a Black man.

The problems here are myriad and enormously damaging, of course. Whole essays could (and have) been written on the portrayal of enslaved people in both the book and the movie and of the White characters’ relationship to those people of color. But I can only tackle so much here. Those elements, while vital to my community’s past and present understanding of the South and the Lost Cause and Reconstruction and Civil Rights, are not what made me understand my role as a White woman. They defined our shared history, for sure, but I had so many disruptors to that narrative that they didn’t define my personal whiteness. Instead, it is the threat posed to Scarlett’s body that lives on in my body. To be a White woman is to be always an object of sexual desire, to be always at risk of being raped. This is one of many lessons Scarlett O’Hara taught me.

Gone With the Wind is a notable example of what film scholars retrospectively call a “Woman’s Film,” a genre that began with the early 20th-century silent films of D. W. Griffith (yep, that Griffith) and peaked in the 1930s and 40s. Historian Jeanine Basinger explains that the purpose of a woman’s film is, “to reaffirm in the end the concept that a woman’s true job is that of being a woman.” As all these films featured white women, every “woman’s film” is a lesson, therefore, in How To Be a White Woman.

Gone With the Wind offers multiple suggestions on How To Be a White Woman, and in elevating Scarlett O’Hara, it departs from one of the common motifs of the Woman’s Film: the doppelgänger sisters, where one actress plays two different women – the good woman who ultimately triumphs and the bad woman, who is shamed or killed or driven out in the end. But in Gone With the Wind, the bad woman wins the day. It is Scarlett, not Melanie, who survives and thrives, Scarlett who embodies the hope of the movie’s final words: “Tomorrow is another day.”

So, there I am in 1992, glorying in being called Scarlett. I identified with the “bad woman,” loving her sass and her strength and wishing for her beauty. She was a fantasy, but just as Susannah Bartlow wrote in her excellent examination of Pretty in Pink, “these fantasies are where our cultures get made.” Scarlett taught me how to be a White woman: confident but subservient, strong but swooning, condescending but sweet to those “beneath” me. She taught me to want to be desired but to fear that desire. She taught me that my desire was less important than that of the men around me. She taught me I could shoot a man in the face, but only if he threatens what I hold most dear.

Watching the film today, I’m still enamored of Scarlett’s spunk. She is still a beautiful woman making incredibly difficult decisions and managing to kick ass along the way. I also deeply admire Melanie’s quiet strength and her generosity. Adult me wishes there could be a third option, one that combines the good and the fierce qualities of both women. Turns out, there is.

Belle Watling is a prostitute and madam in Atlanta, owner of the brothel3 that Rhett Butler frequents, and “easily the most notorious woman in town.” Like Scarlett, she is a woman who recognizes that her beauty and her body are her only currency, and she does whatever has to be done to survive and thrive. Like Melanie, she is a doting mother, who puts the needs of her son before her own wishes when she sends him away to school. She gives a great sum of money to the hospital and allows Ashley and the other men to use her as an alibi on the night they avenge Scarlett’s attack. She is admired by both Rhett and Melanie, with Rhett openly comparing her to Scarlett and finding Belle superior because she is kind and good-natured. And she is always honest about who she is and what she believes. She doesn’t make herself small or stupid or helpless in front of men (as Scarlett often does). She freely gives, embraces her sexuality, and doesn’t apologize for any of it. She may not be as beautiful as Scarlett, but she is humble and thoughtful and truthful.

Obviously, there is no perfect model for Whiteness anywhere, much less in Gone With the Wind. But these days, I’m happy to have shed my old nickname. I am uneasy with the permission a Scarlett O'Hara has granted to White women today. I'm unsettled by the way White women of a certain ilk can draw a direct line from her dismissal of social mores to their own insistence that they can say and do and harm whatever they wish, so long as it makes them feel safe. Instead, I'll try to trace my lineage back to the Belle Watling's of the world. I'd much rather be the White woman who works hard and tries to do right by those around her than the one who barges into every room, making sure all eyes are on her.

Sara Beth West got fired from her first job. By her dad. Since then, she's walked away from many other jobs, including nanny, retail worker, farmhand, choir director, teacher, social media manager, and compost truck driver. Most recently, she left a great job as a public librarian. But the one job that keeps following her around is writer. She writes book reviews and conducts author interviews for Shelf Awareness, Chapter 16, Southern Review of Books, and more. Her Substack, Midweek Dinner, has been on hiatus for a bit as she got divorced and got a job and got (another!) graduate degree, but a relaunch is forthcoming! She still lives in the South.

End notes (from Garrett again):

Oh man, I’ll be sitting with that one for a while. For further reading on Gone With The Wind, I highly recommend The Wrath To Come by Sarah Churchwell. As for a song for the week, what is Scarlett O’Hara if not a woman who was complex, cool and played the field before she found someone to commit to.

We’re doing Taylor Swift’s “The Man” you all.

As always, the entire Song of the Week playlist is available on Apple Music or Spotify.

OK, OK, OK, this is only our second guest essay, but you get the point

It’s important, I think, to note that in the book, this scene is not at all so egregious. In fact, it’s tremendously forward-thinking as Scarlett acknowledges her fear of Rhett’s rough treatment of her, but then feels, “a wild thrill such as she had never known” before giving in “to something stronger than she, someone she could neither bully nor break, someone who was bullying and breaking her. Somehow, her arms were around his neck and her lips trembling beneath his and they were going up, up into the darkness again, a darkness that was soft and swirling and all enveloping.” The next morning, she reflects on the night before, “trying to sort out the jumbled impressions in her mind” and determining that she would not be ashamed: “A lady, a real lady, could never hold up her head after such a night. But, stronger than shame, was the memory of rapture, of the ecstasy of surrender”

There’s another whole essay here on the purity of White women and the WCTU and the Mann Act and the abolition of prostitution. Coming soon!

I haven’t heard many perspectives on GWTW from white women that explore the film critically rather than defending it. I appreciate that. I did my bachelor’s research methods paper on the reaction of Black people to the book and film through Black newspapers. I also read The Wind Done Gone which I found important and engaging. As a lifelong white nonbinary Midwest northerner, I know my experiences and perspectives are different. What I thought of from reading this is how to put the different experiences of white and Black women in conversation with each other. I think what you describe about what Scarlett taught you about your body is similar but also very different from what I’ve heard from Black women. Black girls and women are taught that they are supposed to be concerned with being considered “fast” from a young age. Black women are constantly sexualized and objectified but I feel like our US culture ascribes them less agency over their sexuality and more responsibility for what others perceive than white women. And there is an ongoing contrast between white and Black womanhood. I think this is what we see in Mammy being desexualized but still her body as her labor and loyalty being essential to her character. Similarly with Prissy’s famous line “I ain’t never birthed no babies” being a reflection of the character of deceit and manipulation associated with Black womanhood while Scarlett’s use of lying and manipulation is considered genteel and not generally labeled that way. We call it flirting and persuasive. These double standards rely on a positive idealized white womanhood focused on purity and virtue and a Black womanhood that is inherently corrupt. White supremacy requires creating and maintaining a hierarchy of subordinate values. As many Black activists, particularly women, have said better this is why we can’t eradicate anti-Blackness without also eradicating white supremacy.

Excellent piece that certainly resonates. I was all of 15 when NBC finally bagged the rights to televise GWTW for the first time (Two nights over Thanksgiving Weekend because Wizard of Oz and Ben Hur

-- edit: Ten Commandments. One of the Hestons at any rate! -- had the lock on Easter and Passover respectively.) and the publicity blitz made this last week's Barbenheimer fest look quiet by comparison. So in preparation, I read the novel over several lunchtimes in my school library. I felt so mature tackling a 1000+ page book! And as younger people often do, I read and re-read and read again. It's distressing how much of it still stays with me and how many references are still on tap when the need arises.

Over time, I came to appreciate the slightly subversive quality of a few passages, where Mitchell consciously or unconsciously nailed the Confederacy dead to rights. There's Rhett's "cotton and arrogance" speech at the Wilkes BBQ where he sees the future defeat quite clearly and brutally. Then there's Scarlett's inner-monologue at the post-war gathering in Atlanta where she sits in her ruined green velvet dress stewing over her humiliation at the Yankee jail earlier in the day. As she inventories the threadbare and impoverished people around her still acting out a semblance of pre-war status luxury, she comes to the realization that for her there's no ingrained nobility and only money will make her feel secure again. A similar scene on a porch where she's rolling her eyes and fuming in boredom as veterans begin their war stories again and then she sees the grandchildren on their laps drinking it in. Finally, and most cynically, when Rhett realizes he and Scarlett have pretty much failed at belonging to Atlanta society and this will impact Bonnie's prospects, he launches his social climb back in with a generous donation to the women's group that's "beautifying the graves of our Glorious Dead."

There's another southern female archetype in the book: the one that no Southern or Southern-adjacent girl would want to be. Well, except one: In Dorothy Allison's 1992 novel Bastard Out of Carolina, the lead character Bone reads Gone With the Wind and seethes with anger at its world of class and wealth. It's Emmy Slattery, recipient of Ellen's regal charity and Scarlett's insults, that Bone bonds with.