It's all so weird!

Whether you're tired of asking for money or tired of being asked for money, we all deserve better than the never-ending dance of solicitation

Top notes:

New Barnraisers Project cohorts kick off the end of January. The pre-registration link and an important FAQ document can both be found here.

On December 13th (7:00 PM EST) I get to talk to two of the smartest, coolest people I know ( and Kate Schatz) about a topic we all have some complicated thoughts about: White people writing about race! You should join us!

I am legitimately worried that this week’s piece will feel like a passive aggressive full-length version of what I normally do in this space (make a breezy statement about how I’d very much like you to consider a paid subscription to The White Pages and/or a donation to The Barnraisers Project). If that’s the case, then I failed. If, however, it reads like a sincere appreciation for all the ways you consistently support things you care about (including but not limited to my stuff), then I’ve done all right. We’ll see! But truly- I appreciate all the good things you wrap your arms around, not just the piece of the pie that benefits me. And thanks for being here, week after week. As for those of you who hate my never-ending dance of solicitation specifically… I get it. I’m trying to figure out how to do it better.1

I didn’t know what to expect when I first took a job where I had to ask rich people and their foundations for money. At times, I imagined that as soon as I started pitching, I’d be transformed into a silver-tongued Robin Hood (redistributing wealth and bringing about mass liberation… one printed-out powerpoint at a time). Other times, I’d wake up in a cold-sweat, worried that I had just signed up for an eternity of ominously dark rooms where cigar-chomping robber barons would inform me of the various evil acts I’d have to commit if I wanted their money.

Neither of those premonitions came true. Raising money, as it turned out, was neither a life or death struggle for my soul nor a heroic stand against injustice in all its forms. Mostly, I was just pretty bad at it. I didn’t really understand the donors I was supposed to be pitching, nor how to talk to them. Case in point: I once had a breakfast meeting with a wealthy older couple. I had already received a grant from their foundation. The point of our breakfast was simply for them to meet me face-to-face. We ate oatmeal and sausage links in a large, stone-walled room and I gave what I thought was a compelling, succinct introduction of myself and my work. As soon as I finished talking, the matriarch turned to the nearest foundation staffer— not looking at me at all— and said “well, this one is quite excitable, isn’t he?” I looked down, stirred my oatmeal a few too many times and tried not to notice the remaining staff members furiously taking notes on how to dig themselves- and me- out of whatever hole I had just dug.

To be clear, I dreaded raising money from rich people, but not for any deep, existential reason. I am a straight, cis-gendered White guy. I never had to deal with misogynistic or racist comments from donors. I was never asked to recite the most tragic stories of my life so that my benefactors could enjoy a worldview-flattering Horatio Alger story. I was never praised for being surprisingly articulate nor shut down for being too aggressive. I never had my competence questioned due to biases and stereotypes. If donors didn’t know what to make of me, that was solely because of my various conversational quirks— the dense sentences, the Muppet-esque waving of hands, the volume (oh dear God the volume), the fact that I once made it through an entire day of meetings before realizing that I was wearing one brown loafer and one black wing-tip2. That’s all on me.

Similarly, the fact that I was never asked to betray my deepest values in order to lock down a grant was likely just dumb luck. There have been plenty of devil’s bargains over the history of philanthropy, going back to the field’s founding moments. In 1910, The Rockefeller family established America’s second major foundation. By 1914, it had already set a precedent that scores of foundations would later follow: Using big piles of cash as a mechanism to dictate what kind of social change efforts would and wouldn’t be tolerated.

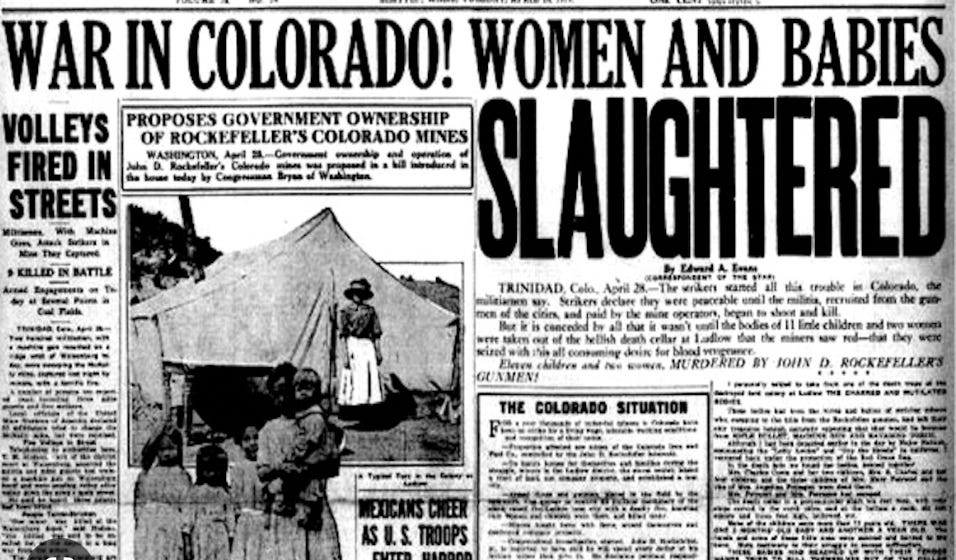

The first test of this “thumb on the scale” approach towards philanthropic giving came after Colorado miners dared attempt a militant strike against a Rockefeller subsidiary. In what came to be known as the Ludlow Massacre, nearly 20 miners and their family members (including babies) were murdered by a strike-breaking militia. Blood was literally on the company’s hands, so Rockefeller’s philanthropic army jumped into clean-up mode. Pivoting immediately, the foundation prioritized grants to anti-union benevolent charities and PR fronts designed to present a company-friendly story of what went down in Colorado.

This playbook— of steering would-be do-gooders in directions less likely to threaten existing power dynamics— was followed a century later by the Ford Foundation, which used its leverage to elevate more reform-minded voices in the Civil Rights Movement and to tamp down the radicals. There are hundreds of smaller stories to the same effect. As a general rule, liberal philanthropists have muted social movements through technocratic meddling. Conservative foundations have never had much use for all that subtlety— their style has been to aggressively fund institutions that will shift the country dramatically rightward. Either way, the outcome is the same. We’ve been asking and giving for a couple of centuries now, but dreams of collective liberation still feel distant.

This isn’t actually an essay about how big money philanthropy typically maintains rather than challenges systems of power. You likely already know that. Even if you hadn’t heard about the Ludlow Massacre of it all, it’s pretty intuitive that a system that involves massive piles of untaxed wealth and sycophancy towards the amassers of that wealth isn’t perfect. There is already a rich bibliography exploring the industry's various philosophical and practical flaws.3

It is also not an essay about how those of you who give out money professionally (either as a benefactor or a staff member at a foundation) should feel guilty about yourselves. I trust you’re doing your best to be thoughtful and generous. I bet that you’ve had plenty of discussions about moving decision-making power closer to communities and giving fewer grants to smooth-talking White guys. All that’s great. Truly. And regardless, we’re all treading water in a river on fire. Neither philanthropists nor nonprofit fundraisers have the One Bad Job. You don’t need another exhortation about your particular Industrial Complex. We’ve all got our own.

Instead of adding my voice to an already noisy chorus, I’ll instead offer a much less profound observation, one that has traveled with me as I’ve moved from fumbling my way through important meetings about large sums of money to passing the hat for individual Barnraisers donations and White Pages subscriptions.

Asking people for money is weird!

I’m making the word “weird” do a lot of work, of course. I’m cramming in a whole range of emotions into a single rhetorical suitcase— fear, scarcity, interpersonal awkwardness, self-consciousness, our past relationship to rejection, etc. etc. etc.. And, of course, those emotions aren’t experienced equally. The weight of both closed doors and financial precarity is disproportionally carried by those for whom our society is already the most hostile. There was a powerful community discussion about this over at Anne Helen Petersen’s Culture Study a month ago. Suffice to say, it’s a knotty puzzle, one thick with layers of race, gender, class, sexuality, disability and neurotypicality/atypicality.

Again, I walk the world with every single form of societal privilege and advantage. I have also spent a good deal of time processing why I truly believe in asking a community of supporters to support my work financially. When I talk about “experiments in mutual aid” and all that, I really believe it! I know I have it immensely easy! And even with all that being true, I still feel an overwhelming wave of panic every time I ask for money for Barnraisers and/or The White Pages. I still cycle through the same emotions after I press send on a clumsy note about how “I can’t do this without your support.” I close my eyes and am flooded with a hundred worst case scenarios, then immediately glance at my bank account in precautionary horror before letting my mind wander towards ill-considered back up plans (“Should I go to Indeed.com and type in ‘Real Job For Somebody Whose Only Skills Are Writing and Talking’ into the search bar? Who’s to say!”).

I am not complaining. Again, I have it very easy.

There are so many people I love (including many of you) for whom the “weirdness” of asking for money or help (and the weight of not receiving it) is significantly more traumatic than anything I’ve ever had to navigate. And it does impact our collective ability to build a better world, even if there aren’t any nefarious cartoon villain donors pulling the strings. Most obviously, of course, is the literal, actual good work that’s not getting done because of all the biases and assumptions and good old boy networks that make it structurally impossible for many people- particularly those on society’s margins- to receive the funds they need. But there’s also the self-censorship and talking-yourself-down and rounding-of-edges that we all naturally do when fear of failure and financial ruin takes the neurological wheel.

I am writing this on Giving Tuesday: a made-up creation of capitalism that exists solely as a reaction to all the other made-up creations of capitalism that come immediately before it. It is a day nobody likes! But one that many of you rely on to balance your organization’s books! And this year it lands directly after the American election season, another period of solicitation that nobody likes! And so, on this day of all days, I should also say this…

Asking for money is weird!

AND…

Being asked for money is weird too!

It is weird to wonder whether somebody else’s relationship to you is merely transactional. It is weird to have two devices (your phone and computer) that are theoretically tools of connection but instead just feel like nonstop solicitation-enablers. It is weird to be on the receiving end of an ask and quietly realize all the ways that you don’t feel safe enough to reciprocate the request. I could go on! But you get it!

So what do we do with all that, us weirded-out human beings on both sides of the asking/being asked equation? Well, I hope we become even more committed to agitating for a political reality where everybody's needs are met without question. Taxation isn’t theft, it’s actually a very efficient means of ensuring that we all share with one another without receiving a million emails about an EXCITING MATCHING GRANT OPPORTUNITY. We should do more of that (taxation and central provision of services, that is). We should agitate for a government that asks us to put our full contribution into the collective pot, but that also does a whole lot more to provide for all of our needs.

I also hope that we increase our appetite and curiosity for relationships where chipping in something annually is a beloved community expectation. Union dues are, it turns out, a pretty elegant funding model for social change. So too (at least in a theoretical situation where the money collected is used for justice and not to further patterns of domination) is religious tithing. There are so many other examples of normalized community sharing, though, many of them right in front of our eyes. While we currently think of commercial co-ops as relatively small-scale enterprises (self-consciously crunchy grocery stores, mostly), that isn’t the case in other countries and wasn’t always the case in the U.S. either. To cite one example close to my heart, in the 1950s, over half of the nearly 9000 residents of my mother-in-law’s hometown of Cloquet, MN were dues-paying members of that town’s multi-business cooperative movement. We have done this before.

I get it, though. For a lot of us, even these steps can be intimidating. Many of us are still in jobs where unionization feels like a far-off dream. Too few faith communities match the qualifications I described in the preceding paragraph. Your local co-op smells too much like tempeh. But there is a simpler principle at play here that is available to all of us: the concept of both caring for a specific institution or community and then making sure you hold on tight for the long haul. There’s a beautiful in-person version of this currently happening in Chicago’s Rogers Park neighborhood. Every Wednesday, a group of housed residents has been serving chili in a local park where a number of their unhoused neighbors live. As they’ve become an increasingly dependable presence, a community has coalesced around them— sharing supplies, clothing, first aid, harm reduction tools and fellowship. It’s the regularity that matters. It’s the “through rain and sleet and snow and hail” coupled with the lack of gatekeeping or means-testing that makes it beautiful. If it’s a Wednesday evening, neighbors will be in the park. If you’re there too, you get chili and love, no questions asked. This is less complicated than we make it out to be.

And yes, charitable giving can follow this principle as well: a modest monthly donation— particularly to an organization that you’re actually invested in learning with/from— does go a long way. So too does supporting the writers and musicians and artists you enjoy most frequently. If you’re curious about what an imperfect model for this might like, here’s a list of the organizations I’m committed to giving to monthly in the upcoming year (as well as the principles behind those choices).

The point of all this isn’t to create a world where we never need to ask for help. It’s to create situations where the stakes of asking for help are lowered because the people we care for, the institutions we value, and the movements we believe will move us forward are less likely to be rocked by precocity and isolation. It isn’t about pretending that we can erase the entirety of each others’s needs, but merely offering one another a more consistent buoy in both fair and rough seas alike.

Giving Tuesday is a dumb made up holiday. That’s not the fault of the people doing the asking today, nor is it the fault of those on the receiving ends of the ask. It is weird and unnatural that we have to solicit this ravenously merely to care for one another, merely to build a better world, merely to make our way through this one. Wherever you are in that collective cycle of weirdness right now, you deserve better. You deserve to have your needs met. You also deserve to feel valued for more than your ability to click a “complete transaction” button. The good news, as always, is that there is more than enough to go around. We just need to rethink how we share it.

END NOTES:

Song of the week:

I decided not to include some of my more speculative observations as to why we hate being asked for money. One theory (for which I have no evidence!) is that many of us who aren’t currently working class still fetishize a working class identity, just without the actual financial insecurity of working class life (and we recoil from reminders that we are, in fact, more financially comfortable). Anyway, if that theory is true (which it may not be! I just made it up!), it would explain the continued inescapability of Walker Hayes’ year-old, Applebee's-referencing mega-hit “Fancy Like.” It’s a rich text! And not entirely un-problematic (is that some unnecessary African American Vernacular English I hear? I think so!). But damnit, I can’t quit it. And neither- if this fan video is any indication- can the rest of White America.

As always, you can find the collected song of the week playlist on Apple Music or Spotify.

White Pages Subscriber’s Only Discussion of the Week:

Last week’s discussion (about feasts!) was very fun. What’s next?

We are about to enter the season of year-end “best of” retrospectives, one of the many milestones that can trigger our insecurities (“Ugh, I didn’t accomplish all my goals this year!” “Spotify told me that my music taste is too basic!” “Wait, do you think the Macarthur Grant people just, like, lost my number? Is that why they still haven’t called?”). So we’re going to combat all that... one non-conditional affirmation at a time. The question? “What Best Of 2022 Superlative Do You Deserve This Year?” No category is too small or superficial. We’re all going to give ourselves credit for something. Paid subscribers… expect that email tomorrow. And in the meantime, keep hanging out in the continually delightful Flyover Politics Discord with us and our pals. Other than Instagram and this literal newsletter, it's the post-Twitter place on the Internet you're most likely to find me these days.

Oh and, as always, I know that asking for help with a subscription is as awkward as asking for money, but if you’d like to join us but can’t swing the financial commitment, just email me (garrett@barnraisersproject.org) and I’ll comp you, no questions asked.

To my credit, I did properly recognize that I am a middle-aged straight White dad and therefore I should not be the hundredth person you encounter today who tries to make a youth-pandering “It’s Giving… Tuesday” joke. Then again, what is this footnote if not me doing just that. Ok, still working on it.

This really happened. And yes, the two shoes felt different. No, I don’t have a good explanation.

A starting point: The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond The Non-Profit Industrial Complex by Incite! Women of Color Against Violence ; Top Down: The Ford Foundation, Black Power and The Reinvention of Racial Liberalism by Karen Ferguson; Decolonizing Wealth by Edgar Villanueva and Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World by Anand Giridharadas

FWIW I found your theory about why financially secure folks find fundraising uncomfortable very compelling! I also just hate the performance of friendship anytime it is demanded--whether in fundraising, job seeking or whatever. Seems like a violation of my favorite part of being human.

One of the more insidious parts of this whole thing is how institutions that were once fully funded through public or private funds (museums, parks, campgrounds, schools, libraries, etc.) are now so dependent on a pay to play + donations funding model. It makes it doubly hard to support your local grassroots mutual aid organization when you also feel like your cultural institutions are going to go belly up without your support.