On being inspired and nervous at the same time

A few thoughts on liberation, organizing and self-righteousness (with an eye towards the current campus protest movement)

“Put simply, we need more people. What do we mean by this? We are not talking about launching search parties to find an undiscovered army of people with already-perfected politics with whom we will easily and naturally align. Instead, organizing on the scale that our struggles demand means finding common ground with a broad spectrum of people, many of whom we would never otherwise interact with, and building a shared practice of politics in the pursuit of more just outcomes.”

“But another big mistake that I was directly responsible for was eliminating organizing … and substituting it with militancy…. We forgot that it took years to get people to the point where they would join SDS. It doesn’t happen suddenly — it happens through building relationships.”

Yesterday morning, students at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, following in the footsteps at their peers at dozens of colleges nationwide, established a Gaza solidarity encampment on that school’s East Side campus. My own presence at the encampment was brief, perfunctory, and fully unhelpful. I was on the way to the airport, just a middle-aged dad with an overly-bulky travel backpack, gawking from the edges, doing the bare minimum. It was, for sure, far too brief of a visit for me to draw any meaningful conclusions about that particular gathering.

What I can say, though, is that I saw students dancing, laughing and busying themselves with the work of establishing a makeshift community. I marveled at a bright cacophony of color—tents and flags and placards— brightening a normally unassuming corner of campus. I listened to announcements about how the medical tent was up and running and watched as a group attempted to hang up their official demands in the face of sudden wind gusts. A few steps a way, an Orthodox Jewish American family and an Arab American elder engaged in quiet discussion before the former group made their way out of the crowd. I don’t know how either party experienced the interaction, so I projected, as I often do, my hopes for the most beautiful version of their conversation.

I can’t say for certain that my hope, both for their interaction and the broader protest, was an expression of naiveté or an act of prayer. By the time I left, the cops still hadn’t shown up.

But still, even for a few minutes, the web-weaving magic that solidarity actions hope to inspire did, in fact, happen for me. I looked at all the faces surrounding me, protestors and bystanders alike, and flashed forward to images from other campuses, of quads filled with pepper spray, tear gas and snipers. In a heartbeat, all I wanted was for all of them to be safe. And then, organically, my basic human desire to throw my arms around the crowd expanded outward—first to Gaza, of course, and then beyond.

I’ve struggled to write about this wave of student protests. It’s so easy to flatten them, either through villainization or romanticization. Especially for those of us whose own college experience is in the rearview, renunciations and tributes alike can sound like two sides of the same paternalistic coin. And then, of course, there is the immense privilege of my perspective, as a White American Gentile. What right do I have to give a Palestinian friend who has lost family members in Gaza my thoughts on organizing strategy? And by that same token, how can my assurance that “I’ve never experienced anti-Semitism at a protest” feel anything but hollow to a Jewish friend for whom chants that reference any type of “solution” (whatever the intent) are especially chilling?

What follows are my best efforts to put my current thoughts in writing, as a pacifist who dreams of an end to oppression, occupation and the carceral state, but who also believes that we will never reach that dream at the barrel of a gun, regardless of which side’s hand is on the trigger.

I am, in so many ways, inspired by and grateful for the protests. They’ve already accomplished far more—in terms of keeping the national conversation focused on Gaza—than I ever imagined possible. When I hear stories about students prioritizing care for one another and resisting the pull to make this moment about themselves as heroes or martyrs, my heart swells. As a person of faith, when I see images of Muslim prayers, Jewish Seders and Christian communion between the barricades, I’m enveloped with a feeling that I can only describe as sacred. When I hear about so many of their strategic choices-- their media discipline, the clarity of demands, the connective networks—I’m humbled by their activist wisdom.

I’m not surprised to see images from refugee camps in Gaza—tents with “thank you students” scrawled on the side. Of course, the protestors’ actions have filled hearts half a world away. That’s how solidarity works.

All that is true. So true. And also…

I’ve been so anxious this past week. I’m worried about student safety, of course. I know full well that we haven’t seen the last of the riot cops.

Beyond the short-term, though, I’m nervous that this, like so many past movements, might fall short of its beautiful potential. Recognizing, of course, that there are concerted right-wing efforts to try to paint the protestors in the worst possible light, it still broke my heart to earn that one of the primary spokespeople for the Columbia University occupation had, as recently as January, made faux-revolutionary boasts about how Zionists “deserved to die.” And it’s not just one loud voice on one campus. The movement can be too quick to brush aside the perspectives of Jewish activists who offer good faith feedback about why they still don’t feel fully safe in protest spaces, often with the justification that they should be more like the Jewish protesters who don’t share those concerns. And I clench up when I read some of the statements from encampments that lean on strident, “if you’re not 100% with us we don’t want your support” red lines. To borrow the words of abolitionist activists Kelly Hayes and Mariame Kaba, I worry that all this serves to make justice spaces more like clubhouses than movements.

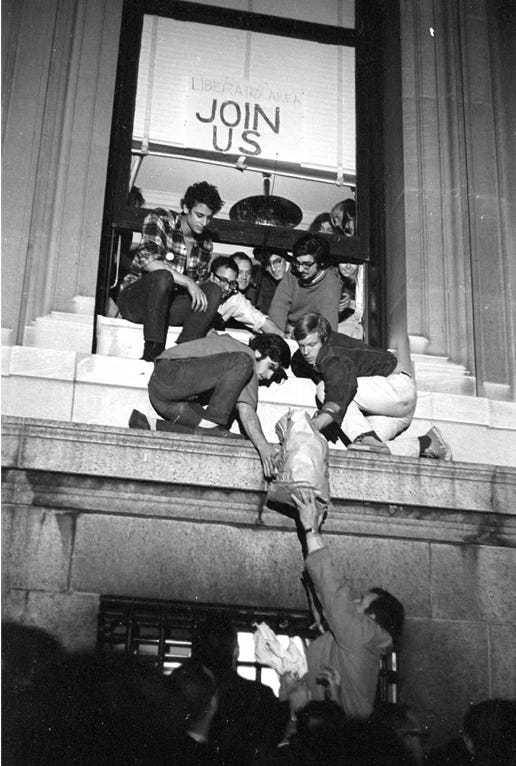

To be fair to contemporary activists, so much of my fear stems not from their mistakes, but from all the ways previous generations, my own included, stepped on so many predictable rakes. As Mark Rudd, the face of the 1968 Columbia uprising, later reflected, his generation of occupiers quickly lost the plot in a haze of revolutionary self-righteousness. They forgot that the victories of the Civil Rights Movement and the early rise of the mid-century Left were fueled by a commitment to organizing and base-building. The first wave of ‘60s activists still had tangible ties to the labor movement. They honed their skills in trainings at the legendary Highlander School. And they understood, not intellectually but through on the ground experience, that social change comes from loving all people—especially those who weren’t already on board for radical politics. It meant building relationships with the unconvinced, making time for their fears and hold-ups, learning the motivations that might inspire them to join the movement.

Organizing, notably, didn’t mean compromising principles or demands. It did, as it does today, though, entail a curiosity about and love for people, including those who were unlikely, for a number of reasons, to storm a barricade.

As the decade went on, though, and the siren calls of individualism and all-or-nothing political fundamentalism overtook the bourgeoning protest movements, self-proclaimed leaders in both the White and Black Left increasingly turned from a theory of organizing to revolutionary vanguardism. They fetishized violent, strident revolutionaries like Che Guevara, casting aside anybody without an automatic rifle and a manifesto as a bourgeois moderate. They closed themselves off to those who didn’t already share their perfect politics. And the most strident amongst them, like Rudd, vacated the movement altogether in favor of tragi-comic pseudo-revolutionary groups like the Weather Underground.

My own college protesting years were less heady than the anti-Vietnam era, but we also accomplished far less than either that movement or our anti-apartheid forbears. We tried and failed to stop two wars being waged in our name. And to our credit, very few of us ever wasted our youth pretending that a few homemade bombs would bring about the revolution. But we made our own mistakes. In many cases, ours were crimes of omission. The Iraq and Afghan wars waged on long after our marches dissipated. We didn’t set off any bombs, but neither did we welcome many new communities into our ranks.

I share these fears not because I believe that the current protest movement is fated to walk the same roads as their forebears, but because I hope with all my heart that they don’t. I dream that they can bear witness to their own human tendency towards self-righteousness and in-group-signaling but pivot their hearts and dreams more expansively.

Doing so, though, will take an intentional set of choices. It’ll take doing away with the myth that you have to tone down your principles to welcome others in (organizing isn’t about moderating your stance, it’s about curiosity towards those who aren’t automatically swayed by that stance). It’ll include recognizing that not all voices cautioning against anti-Semitism are doing so in bad faith. Many, in fact, are earnestly looking for their way in to the current movement. It will take outreach from organizers with racial and religious privilege towards communities that still are largely disengaged from the movement—especially White Evangelical spaces that still form the backbone of U.S. support for the Israeli government. And it will take imagination about what connections beyond campus walls still need to be made. Last week, for example, protestors at Emory University issued a wide-ranging invitation—to students at other Atlanta campuses, to high school students, to campus workers—to join them. An invitation is easy, though. Coalition and cross-class, cross-institution organizing is harder, but necessary.

I wish so desperately for the current assault on Gaza to end. I wish even more for this to be the last war in the Levant, for the occupation to cease and for the work of reparations, justice, and collective dreaming to begin. I dream of liberation for all, which means that I dream of a protest movement that possesses both critical eyes towards oppression in all its forms as well as open, expansive hearts. I hope we remember that the charge that we are not free until we are all free is not just a slogan; it’s a challenge to build and sustain growing movements that stay true to our principles but keep our arms spread open.

End notes:

-There are some understandable reasons why organizing movements veer into self-righteousness. There are also some bad reasons. I wrote a memoir about trying to unlearn some of the bad ones and how beautiful it is to care about community and relationships instead. If you haven’t gotten your copy, I think you’ll enjoy it.

-I am speaking in Lynchburg, Virginia tonight, giving a book talk and organizing workshop at Lynchburg Grows. 6:00 PM. Come through, friends! In related news, I’m writing this from Lynchburg and can report that it’s a lovely town.

-Speaking of organizing workshops, today is the deadline to register for the May 2nd Barnraisers Project Mini Session (but if you miss that deadline, have no fear— there are two more sessions after that). Info and registration here!

-In other news, yes, I will be reading Kristi Noem’s second memoir when it’s available, because I’ve locked myself into a lifetime of reading Kristi Noem books, apparently. I don’t think I have anything trenchant to say about her dog killing anecdote. It sounds like the kind of thing I wouldn’t do, but then again I’m not a real leader and I’m incapable of making tough choices.

-Speaking of following up on past White Pages, it took a while but the Finnish Social Security Agency finally released the 2024 baby boxes (they didn’t want to reveal them until they had gotten rid of the 2023 stock). My verdict? Love them, of course. Was that in doubt?

-Ok, one more update. Last week’s essay about a delightful candidate in a rural Wisconsin district did, in fact, find its way to the delightful candidate in question. Check out her (not surprisingly, delightful) reaction in the comments.

Forgive me. I'm about to ramble for a moment. But I think part of why our movements, particularly on the Left (I can't speak for those on the Right, though maybe they fall prey to this. I have no idea.) veer into self-righteousness and purity politics is because we don't actually know how to grapple constructively with the reality of harm-- the harm we do to each other and the harm all of us commit at one time or another. We want to act as if there is some reality in which harm doesn't exist and if we keep weeding out all "those people" then someday we'll all be perfect and untroubled and righteous together. The irony isn't lost on me in the current moment that the best writing I've encountered on how we can deal constructively with harm in relationship and community was written by a Jewish rabbi based on the work of a 13th-century Jewish philosopher, Maimonides. It is Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg's incredible book, On Repentance and Repairs: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World. I highly recommend it.

https://bookshop.org/p/books/on-repentance-and-repair-making-amends-in-an-unapologetic-world-danya-ruttenberg/17845057

Part of staying open to other people who may not align perfectly with you is wrestling (internally and together) with how to confront harm realistically, with an eye towards transformation. Until we can do that we'll keep shying away from the relationships, alliances, conversations, and confrontations that could actually change our world, instead choosing what keeps us comfortable.

Just wanted to say I loved this piece, and I think it's exactly what I needed to hear right now. Thanks, Garrett! I also cannot stop thinking about the parallels to the 1960s re: "our current times," even before this wave of protests but especially after. It is my Roman Empire, you could say! Even though a lot of the dreams of the '60s did not come true, I think that analyzing what did and do not work is so valuable in this moment.