Partially full hearts, half-closed eyes... can't win

On the mess we're all in when love is conditional and empathy is a gated community

Hello! It is very tough out there and I hope that you are OK. As always, let me know how you’re doing and if I can help. One small, insufficient offering I’ve got right now: There is another Barnraisers Project organizing training coming up! They’re very special and offering them has changed my life in some very real ways and I won’t go on about them here but if that’s intriguing you can read about them here and register here (by September 8th).

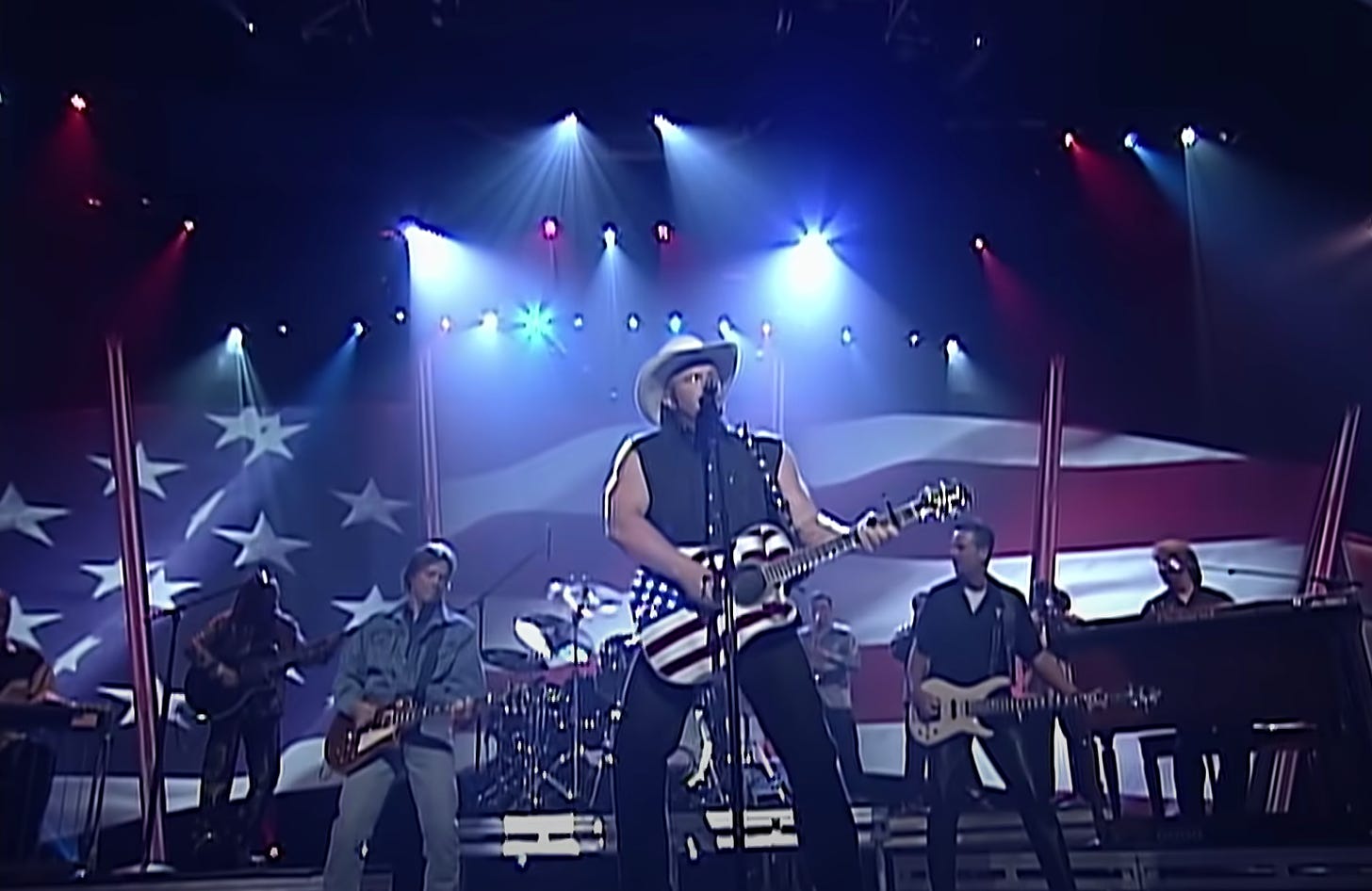

Toby Keith wrote “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue” in twenty minutes. It is a post-September 11th piece of stepped-on sub-Haggard jingoism about wanting the United States military to kill thousands of Afghans on your behalf. It is also about how Toby Keith missed his Dad, a proud veteran who died in a car accident in 2001. Most of all, though, it is an absolute mess of a song, one that stood out for its aggressive misanthropy even in a thoroughly blood-thirsty early-aughts America. None of that would impact its popularity though— the single would eventually go platinum and ended up being Keith’s largest-ever crossover hit.

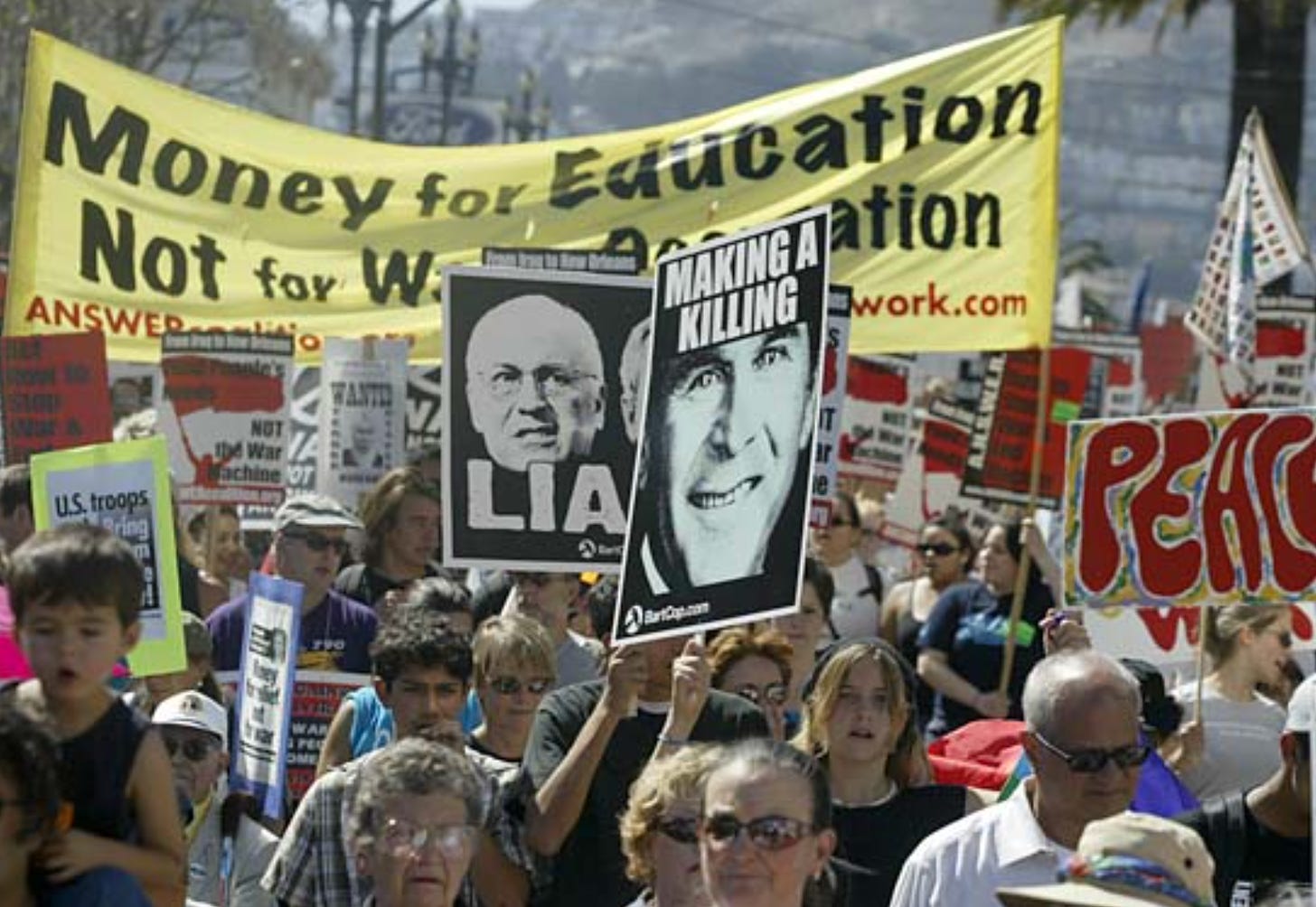

When I say that “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue” was inescapable for a couple of years, I don’t merely mean that it was played on the radio a bunch. I mean that if you were visibly opposed to the U.S. starting wars overseas- either in Afghanistan or Iraq- people would literally find an excuse to play it directly at you. I was in college at the time, at a hippie-ish Quaker school with a large Middle Eastern student population— arguably one of the safest anti-war bubbles possible. Even there, though, we couldn’t hold an anti-war vigil in the center of campus without a couple of bros in a nearby dorm blaring a medley of “Courtesy of…” and Outkast’s not-explicitly-pro-war-but-vague-enough-to-be-repurposed-as-such “Bombs over Bagdhad” at us over and over again.

I’d later learn that those bros with the speaker were feeling scared and worried about family members deployed overseas, which legitimately must have been tough. The nuance of that emotion is lost slightly when your sorrow and fear is expressed through the high-volume deployment of lyrics like “We’ll put a boot in your ass, it’s the American way” onto a crowd full of Iraqi and Palestinian students.

We’ve been at war in Afghanistan for twenty years. Over 150,000 Afghans died in that war, alongside over 6000 Americans. For twenty years, none of those deaths were newsworthy. None of them were mournable. Barely any of them were noticed by the general American public. It is dizzying then, to live through these past two weeks of Breathless Public Empathy directed at a country who we were first taught was merely a bombable terrorist-hoarding wasteland and were later taught to ignore altogether. We are now Noticing Every Tragedy in that corner of the world again. We are Mourning Every Death. We are Very Concerned about Afghan Women.

On one hand, there’s nothing notable or interesting about this about-face. We know this is all cynical, that when you build up an unwieldy national security apparatus with such ingrained ties to the nation’s largest media ventures, that talking heads will say whatever needs to be said to keep the war machine running. I’m not sure why I should expect anything different— you don’t see the head coach for the Detroit Pistons go on MSNBC to argue that what the world needs now is less basketball.

What I can’t get out of my mind, though, is what lessons we learn from a culture where empathy is selective and conditional— where the contours of who is afforded dignity and respect have more to do with the point we’re trying to prove in the moment than any principle of universalism. Our network news media cares loudly and intensely (and let’s be honest, patronizingly) about The Good Afghans only when doing so can help justify the bombing of The Bad Afghans. Our urban progressive text chains display nuance and empathy when we learn about unvaccinated clusters in Black and Brown communities, but wish death and disease on “ignorant anti-vaxers” in rural, Trump-voting counties. We show up to school board meetings when we perceive the slightest threat to our White children (the “threat” in this case, can be everything from a conservative district’s fear of the 1619 Project to a liberal family’s fear that their “sensitive” “gifted” child won’t get their special gilded class, school or program), but never for the well-being of every student in the system. It’s not a problem of crocodile tears— the tears are all too real, in fact— it’s that there are strict boundaries as to who is deserving of those tears.

It should be no surprise, then, that a law like Texas’ SB8 is the rock that brought down the shaky dam that was America’s commitment to reproductive health services. [An aside here— I know that I have a number of readers who are opposed to abortion on theological grounds. As always, I’m glad you’re here and I’m always happy to hear from you as you speak from your heart. Thanks for letting me speak from mine; I hope you understand how profoundly many of your neighbors are hurting right now]. Since its coalescence in the 1970s as an organized political movement, pro-life rhetoric has consistently relied on the weaponization of people’s empathy for the unborn in a way that requires denying empathy and sympathy for human beings seeking abortions. Abortion-seekers are worthy of sympathy if they make the “correct” choice (adoption or raising the child) but are either erased or made into “baby-killing” villains if they make the “wrong” choice. The natural endpoint of that situationally empathetic rhetoric, then, is this absolution abomination of a law, which deputizes citizens as bounty hunters against anybody aiding and abetting a Texan seeking an abortion. The message is clear: If you believe that life begins at conception, the way to show how much you love and care for the unborn is to personally serve as a temporary agent of punishment and retribution against your neighbors.

There is one way to see all this, which is that we are all just addicted to cruelty and harm, that there is no “American way” by which Toby Keith might mourn his recently deceased father other than the mobilization of thousands of “boots up the ass” of Central Asian villages. And for sure, most days it seems like we are nothing more than a nation of neighbors-turned-self-deputized-cops, alternately narcing on or wishing death upon each other.

If it were as simple as that, though, there would be no need to couch any of our ugly moments in appeals to empathy. If we were merely cruel, vile creatures, there would be no need to cynically appeal to our empathy when drumming up support for a war or a draconian new law. The problem isn’t that we don’t care for each other. It’s that living in a culture of situational care, of deeply conditional love and of spiky guard rails on who is or isn’t your neighbor has left us all with a deeply atrophied imagination of what a culture of love actually looks like.

There is a line in James Baldwin’s No Name In The Streets that burrowed its way into my soul this summer and that I just can’t get over. If you haven’t read No Name…, it’s Baldwin at his most heartbroken, wrestling with the end of the ‘60s, the murder of MLK and Malcolm X and the government’s war on the Panthers. It’s a moment in time where he could be forgiven for turning his back on humanity. His heartbreak, though, stems not from nihilism but from his realization that he just can’t quit us. Here’s the line that slays me.

“Incontestably, alas, most people are not, in action, worth very much; and yet, every human being is an unprecedented miracle. One tries to treat them as the miracles they are, while trying to protect oneself against the disasters they’ve become.”

We are so disastrous to each other. We will, I hate to say it, continue to be so. And as always, the stakes of how disastrous we are to each other will not be dealt out nor experienced fairly or equally. Our collective and individual disastrousness is worth raging about, it’s worth screaming about, it’s worth all our grief.

And yet… we are also all miracles. And just as there is no productive way forward that isn’t fully honest as to how disastrous we are to each other, there is also no way forward that doesn’t involve the constant reaffirmation of all of our potential miraculousness. We must be honest about the messes we are while also being afforded a belief-beyond-deserving that we could perhaps be better.

You may have seen a headline last week about a cruel Wisconsin school district that wanted to opt-out of universal Federal free lunch programs. There were big, bold, infuriating, easily-critiquable quotes from board members about how they didn’t want their children to get “spoiled by” something as indulgent as… food. I spent far too much time being distracted by responses to the article— I kept reading and scrolling as one by one, good progressive people showcased how much they cared for the children of Waukesha County by calling the adults in that community evil, heartless, unforgivable ghouls.

What didn’t make national news, however, is that this week the Waukesha county school board voted 5-4 to remain in the Federal program. Every child in Waukesha schools will, in fact, sit down to a free school breakfast and lunch this fall. And that victory happened in part because of the social media backlash (though it appears that their temporary virality caused many board members to dig in their heels deeper), but much more so because a group of parents in that community have been organizing for months to make sure their board did the right thing. In doing so, they held both of Baldwin’s truths about humanity in their hands. They didn’t ignore the truth of their-neighbors-as-disasters, but they stayed true to the potential that those same neighbors could still be miracles. That’s why organizing is the only force that truly can build a better world— it lives in the sacred zone between our justified rage and our necessary hope.

We are all miracles even when the cameras are off.

We are all miracles even when others gain nothing and prove nothing from treating us as such.

We are all miracles even when we are disasters.

It has been a very bad week. It has been a very bad summer. It has been (another) very bad year. I can’t foresee a world in which any of this gets easier anytime soon, nor can I foresee any way that we can make it better— from flipping elections to rebuilding torn-apart communities— that doesn’t require us to turn closer and closer towards one another.

We are stuck with each other, my friends, even when we wish with all our hearts that we weren’t.

We also need each other, friends, in ways that are more beautiful than we can ever express.

Three songs this week, for Texas:

Love this one so much, thanks Bucks. You have moved into my head and heart and reminded me to pause in all of my spiky guard rail moments. What a pain in the ass. What a gift.

“It’s that that living in a culture of situational care, of deeply conditional love, of spiky guard rails on who is or isn’t your neighbor has left us all with a deeply atrophied imagination of what a culture of love actually looks like.” ❤️