The week of the dad

There has been so much talk about Tim Walz, dad. And that's beautiful. And also....

I logged onto the book club an hour late, but I had a good excuse. I had been parenting all day, as one does when you’re the partner with the more flexible day job and you successfully pieced together a partial but not at all sufficient patchwork of summer childcare and camps. My wife kindly took over in time for me to jump on a bit after 7:00 PM. The club was hosted by

and Miranda Rake from podcast, but this particular discussion was about being a dad. The guest of honor was Lucas Mann, author of Attachments, a lovely essay collection about fatherhood.I missed a good conversation, by all accounts, but I made it in time for the last question. The dad who asked it was older— he became a father in ‘72— but he was curious about the younger dads. “Do you talk to other dads about being a dad? I wish I had done that.”

The consensus reply was “not nearly enough, probably.” A few theories were thrown out. Maybe we are too competitive, somebody said. The broader epidemic of male loneliness was referenced. One of the two hosts talked about begging her husband to set up a little dads group, just something simple, Sunday night at the brewery. “What would we talk about?” asked another. “Maybe ask moms what they talk about with other moms” came the reply.

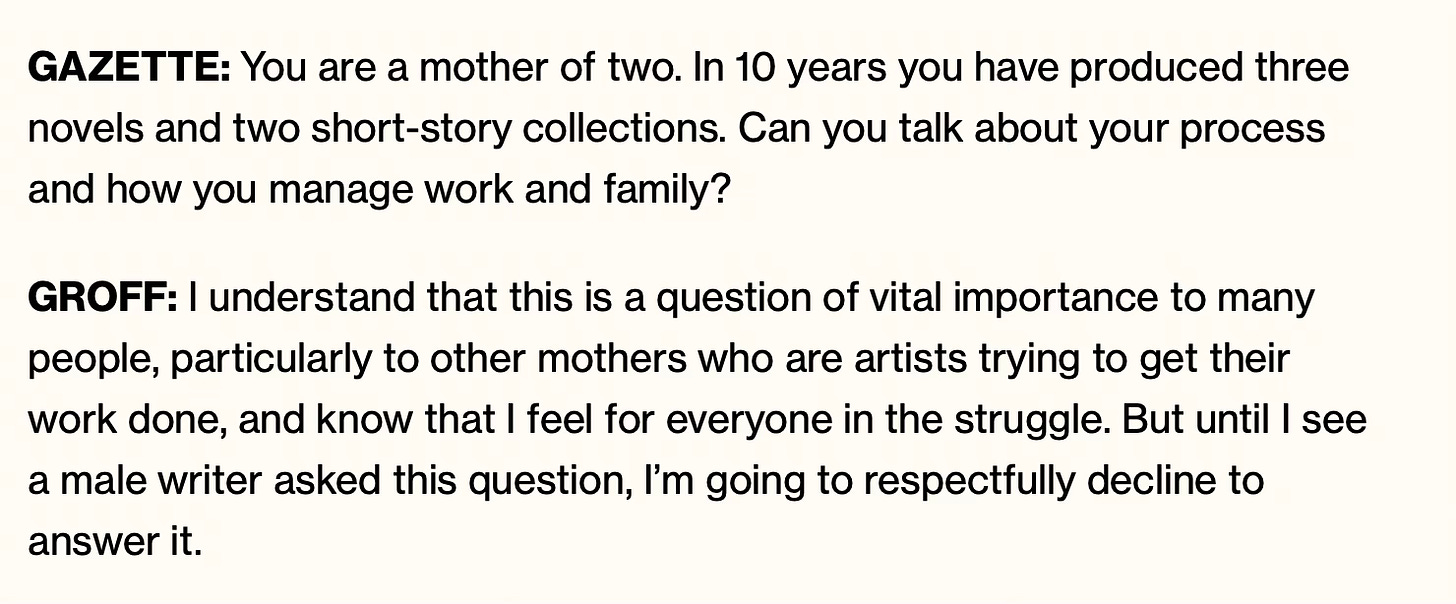

I didn’t answer out loud, because I was too busy going down my own rabbit holes. I thought about how rare it is that I’m asked to think about being a dad outside the four walls of my house. I thought about the quote that the author Lauren Groff gave in 2018 when interviewed by the Harvard Gazette. My friend Lyz Lenz (of

) shared it a few weeks ago, and I haven’t been able to get it out of my mind since.Lyz and I have both been promoting books this year. She’s a mom, I’m a dad. I’d say “if you’re wondering which one of us has been asked the ‘how do you manage work and family?’ question and which one hasn’t” but you’re not wondering that at all. You know the answer and you’re right.

The book club conversation with the kind-hearted dads wrapped up and I thought about all the truisms that get repeated when we talk about fatherhood, particularly fatherhood in heterosexual relationships,. What do we know to be true about fatherhood in 2024? So much and so little. I am told that dads tell corny jokes and are not cool and think that we’re doing an equitable level of household work even though we’re not. I am told that we feign learned helplessness and that is a problem but at least we are more likely to tell our children we love them than would have been a decade previously. Who is a dad? A wearer of cargo shorts, a compendium of thoughts about large boats and World War II. Somebody who doesn’t cry, except when the chorus hits in Thunder Road. An active member of Wilco, or at least somebody who could be an active member of Wilco.

We don’t say out loud that we are mostly talking about White dads. Straight dads. Cis dads. Dads who work outside of the home, likely behind a computer. But that’s often what we’re saying. There was an article in the New York Times about the Congressional Dads Caucus mentioned that one of the members, Dan Goldman, represents “the dad stronghold of Park Slope.” The presumption there is that there are other places— the South Bronx, Pine Ridge, Appalachia— which are not “dad strongholds.” What is a dad stronghold, again? It depends? What’s a dad?

I don’t know if it’s safe to say that fatherhood is having a moment in the public consciousness right now, but it’s undeniable that one dad in particular is having a moment. At least temporarily, we are all living in Tim Walz’s world, which means that we are celebrating two things that are fairly central to my identity— the upper Midwest and being a dad. Are you aware that Tim Walz is a dad? Of course you are, but that’s not what we’re talking about. The popular conversation, at least as far as I can surmise as somebody whose work day currently begins at 7:00 PM and ends whenever I fall asleep (again, children! summer! It has been very fun but I am exhausted!), is less about Tim Walz as the literal father of a twenty-something daughter and teenage son, it is about how Tim Walz IS Dad. Like as a brand. Like as a meme. He has “dad vibes,” I am told, or “big dad energy.” The jokes are very funny. The heartfelt sentiments are beautiful. I hope it doesn’t sound like I’m rolling my eyes at any of this.

I have read that people wish that Tim Walz was their dad. I have read that Tim Walz reminds people of their dad. I have read gushing tributes to the way he talks about how he’s been changed by his daughter Hope’s prodding on issues like gun rights or what he and his wife Gwen have learned from their son Gus navigating the world with disabilities. I have read, heartbreakingly, that there are a number of White people with Boomer and Gen X fathers who say that Tim Walz reminds them of who their dad was before they started mainlining Fox News and became a misanthropic grump. I can tell that there’s so much embedded in even the quickest tossed off joke— a longing, a nostalgia, a thirst. For what? For earnestness? For male vulnerability? For a public figure that very well may wake up in the morning thinking only about focus groups and polling but who we can at least imagine wakes up thinking about the text he got from his daughter, about whether she’s safe, about whether she’s changing her oil frequently enough?

Whatever it is, it’s worth noting again. Tim Walz is not your dad. He is an actual dad to two human beings, just as Kamala Harris isn’t Drew Barrymore’s “Momala” but she is “Momala” to two other specific people. Tim Walz is a dad just as J.D. Vance is a dad and Donald Trump is a dad and billions of us are dads. By that I mean that they and we are dads in the same way, or that we have the same approach towards fatherhood, or that those approaches are equally harmful or helpful to ours and other kids. They and we are dads in the moments when they explicitly and self-consciously perform fatherhood— when young or grown children are trotted out for photo ops— but they are also dads in the much more frequent moments when it isn’t mentioned. When we talk about their professional aspirations and foibles, their ambition and drive, their presentation of themselves as leaders and statesmen, they are still dads.

What I am saying, I suppose, is that “dad” is not just a vibe or a meme or a list of jokes about a very specific variety of White guy who wears Carharrts and knows how to stain a deck. Fatherhood is not more important than motherhood, nor is it more important than being an adult human being who isn’t a parent. It is, however, a deeply consequential identity, one that has both shaped and is shaped by so many rotten societal hierarchies but which also, because it is at its core about a relationship you have to other human beings, can potentially be so much more beautiful than that.

I started this essay while my kids were asleep, but it’s the next morning now, which means that I’m back on the clock, fitting this in between breakfast and Pokemon. Not surprisingly, they were amenable to my proposal that they got to watch extra Olympics while I finished this essay. They are seven and eleven now. In all honesty, we’re having a blast this summer. I’m in one of those stretches of fatherhood where, while I still have so many questions about what I’m doing well or poorly, whether I’m sticking the various balances of support and challenge, independence and interdependence, presence and absence, at least we’re all having fun together. Maybe a few years from now I’ll feel like I’m terrible at this— at being a dad, at being a co-parent, at being a guy married to a woman. I’ll bemoan what I wasn’t able to be for my kids, or regret what they wish I was but wasn’t. And then the next day things will feel differently again.

I love that we’re talking so much about one particular dad, about dad as meme about dad as joke. It is a deeply limited and reductive conversation, because of course it is. It reflects all our society’s biases about who and doesn’t belong because, again, how could it not?

But at least we are talking about this thing, fatherhood, this thing that so often we don’t talk about with any texture, nuance or imaginary hope. We’re talking about something that so many of us are much worse at the less we talk about it, the less we’re asked to consider it, the less we are curious about it. I don’t need us to talk about fatherhood more because I need even more societal conversations be centered on Men And Our Needs. But I do want dads to be expected to consider themselves as dads, especially in moments (like electoral politics) when we we’re so often allowed to be anything but a dad, where the implications that our own vainglorious hero's journeys have on families and spouses and divisions of labor and emotional labor are allowed to be pushed to the side.

So I should talk more about being a dad. By that I don’t mean in this space, though goodness knows it’ll keep coming up. I do mean with other dads. We haven’t figured it out: balancing dad-ding and work and life; the dynamics of gender and power between us and our kids; the dynamics of gender and power between (for many of us) ourselves and our spouses; te role of race and class in all this, about how those of us dad who are already propped up by societal hierarchies avoid further reinforcing them in our quest to do “what’s best for our kids;" and, of course, all the mental junk and unhealed stuff we carry with us and how frightened we are that we’re gonna just keep passing it down.

I should talk more about that more. We should talk about that more. And in more ways. Because I love that we love Tim Walz as dad. But we also live in a country where “fathers of daughters” pass laws that put women at risk and that demonize trans kids. We live in a country where parents are separated at the border, where dads in low income Black and Brown neighborhoods are locked up disproportionally and then lectured on how they’re contributing to “an epidemic of fatherlessness”. We live in a country without paid family leave and universal childcare and any social democratic safety net that could potentially undo pernicious gendered care hierarchies. And we live in a country where the art of being a decent dad is just really, really hard.

It has been a lovely week. Goodness knows that there are so many worse things to discuss than a guy from Minnesota who clearly loves his kids getting a promotion. We’ve talked about one dad, sometimes substantively, sometimes superficially. And that’s all well and good. I just hope we don’t stop there.

End notes:

While I’m fortunate that my wife has a traditional day job that pays our primary bills, this too is work, this job I have that allows me to be the flexible caregiver. That’s to say, if you found this or any of my essays helpful, I’d love if you’d consider chipping in to help keep this space running. What helps? Becoming a paid subscriber, for sure (the perks ain’t bad, by the way), but also buying a book, donating to the Barnraisers Project or whatever works best for you.

I normally use Thursdays for community discussions with paid subscribers, but sometimes you’ve got an essay in you that just needs to get out, you know? Thanks for your understanding, paid subscribers. We’ll be back next week.

There are probably more typos in this one than normal. I’ll go in and fix later, I promise, but now it’s time to be a more active dad again. Watching Olympics is fun and all, but it’s time for me to put down the laptop.

If this feels like a companion piece to this essay from a few weeks ago, well, I guess that makes sense. This is the summer where I’ve delighted in dad-hood being activated in public in new ways. Shout out Dads For Kamala. Still lots of ways to plug in, if you’re interested.

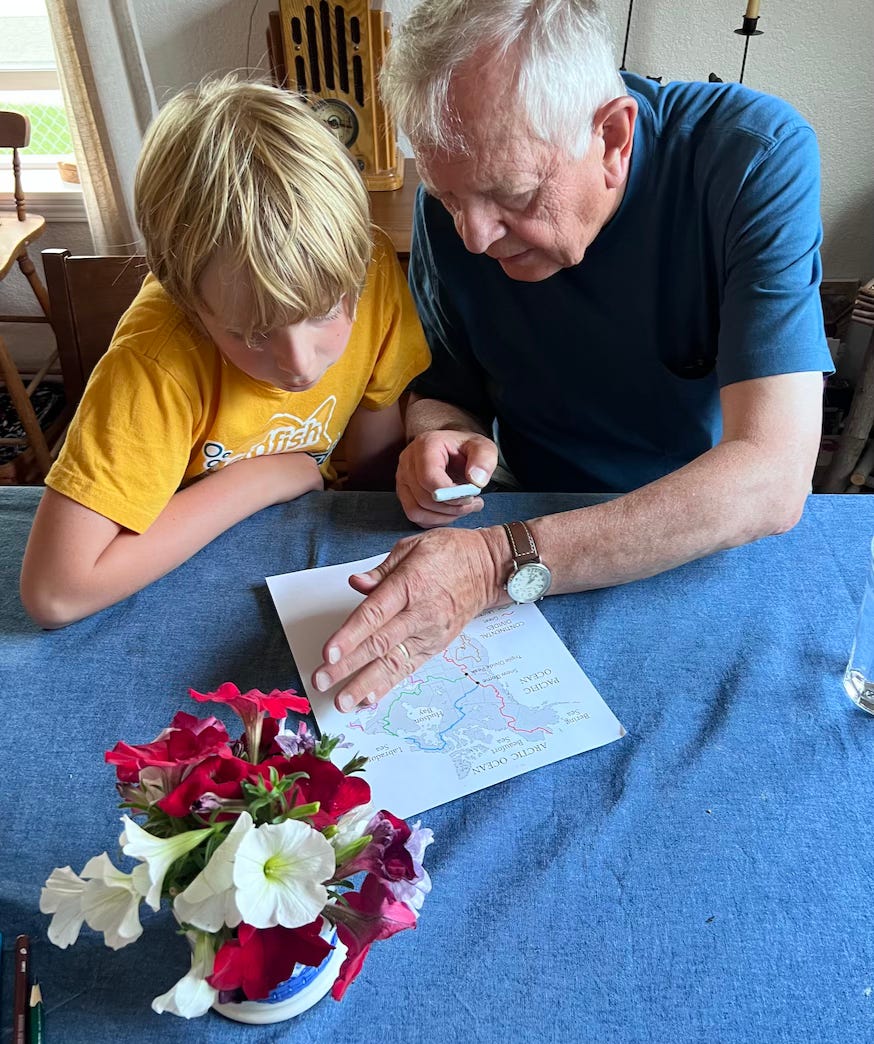

Tangentially ... If my White Midwestern dad were still with us, it would have been his 100th birthday this past Sunday. So I've been thinking about dads, and my particular dad, a lot. He was Fun Dad until I hit puberty with all its turmoil and confusions, and then he became Ghost Dad. I must have been close to 40 before he ever said "I love you" to me (we both cried). In one of the last conversations we had, when dementia was turning him back into Ghost Dad, he told me about coming home from the Pacific in WWII, landing in Seattle on New Year's Eve, having been ripped from his rural family, witnessed death, experienced dengue fever, been far away for far too long, been aged beyond his young-adult years. Mom said it was the only time she had ever heard him talk about his wartime experience out loud. He didn't know a sparkplug from a server, but he sure would have loved Wordle. He would have reveled in this political moment. He would have hoped with me. He would have gone door-knocking with me, if I asked him to. What a blessing, to know that about my nerdy progressive dad.

Watching all the memes and tweets about Tim Walz has been really funny, but you bring up a great point, Garrett, about the connectivity of dads.

I heard an NPR story several years ago about the epidemic of male loneliness and it resonated big time. I have one really good friend. We grew up together, talk or text at least daily, have been there for every one of our big life events, the whole nine yards. Other than him, it’s crickets. I have acquaintances, but not friends. Then I looked around at other men I know and saw the same thing. I started making an effort to initiate purposeful connections with other men I know. I started texting randomly to grab a beer or dinner. Sometimes it’s just two of us and sometimes we need a bigger table. It’s been pretty great overall, but I learned something very quickly. Purposeful connection is hard work. I go too long between sending out invites and often find I’m sending them when it’s convenient in my life which suggests that I’m not prioritizing this as much as I’d like to believe I am.

Regardless, I’m determined to keep it up. We need to be talking to each other and sharing thoughts about being dads, parenting kids, being husbands, masculinity in general, and how to do all of this. We might as well just admit that we’re all scared to death pretty much all the time and work together to get through it. It sure beats an epidemic of loneliness.