Content warning: This essay discusses political self-immolation. While I believe that it is important to analyze that particular act as being distinct from other forms of suicide, that doesn’t change the fact that this is a highly sensitive topic. That’s to say, I understand if any of you need to skip this one. If you or someone you know is considering suicide, please contact the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline by dialing 988, text "988" to the Crisis Text Line at 741741 or go to 988lifeline.org.

“Like the Buddha in one of his former lives… who gave himself to a hungry lioness that was about to devour her own cubs, the monk believes he is practicing the doctrine of highest compassion by sacrificing himself in order to call the attention of, and to seek help from, the people of the world.”

-Thich Nhat Hhan, 1965, in a letter to Martin Luther King Jr.

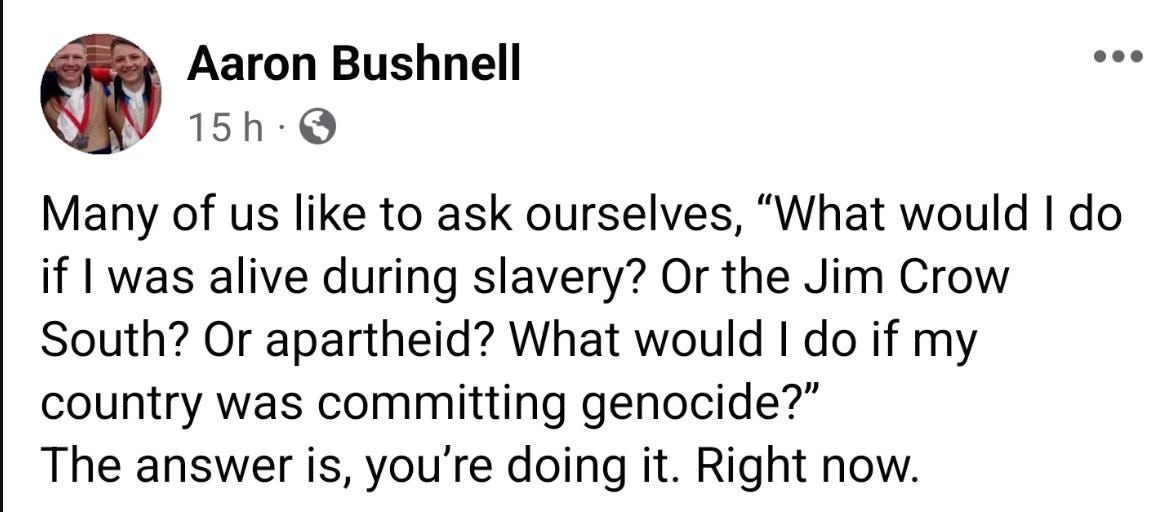

Yesterday afternoon, Aaron Bushnell, an active duty member of the U.S. Air Force, set himself on fire in front of the Israeli Embassy in Washington D.C. He did so, in his own words, in order to “no longer be complicit in genocide.” He repeatedly yelled “Free Palestine” as the flames engulfed his body.

Bushnell is not the first activist to self-immolate in opposition to Israel’s ongoing war in Gaza. His protest follows a similar December action in Atlanta, where an anonymous woman set herself on fire in front of the Israeli consulate. Bushnell’s protest has received more attention than that December action, likely because it was deliberately livestreamed. That’s the point of self-immolation. A temporary seizing of attention. Not to make the person on fire famous, but to ensure that a broader tragedy isn’t ignored.

Immediately before dousing himself in a clear liquid, Bushnell explained that while he was about to engage in “an extreme act of protest,” that it was nowhere near the level of extreme violence being perpetrated on civilians in Gaza by the U.S.-backed Israeli military.

I’ve written about self-immolation before. It was a hundred days ago, when this particular war was still in its infancy. Just a few days previously, an unidentified Congolese man had set himself on fire in Kinshasa. He was protesting his country’s civil war, one that is frighteningly easy for me to ignore in spite of all the ways I’m tethered to it: as an American, as an owner of a cell phone, as a human being.

Self-immolation is perhaps the oldest form of civil disobedience. For as long as there has been empire, there have been human beings setting themselves on fire in order to confront power, death and cruelty. In 300 AD, Christians persecuted by the Roman Emperor Diocletian set fire to his palace and then threw themselves into the flames. In 393, Faru, a Chinese Buddhist Monk protesting an illegitimate regime, wrapped his body in oiled cloth and swallowed incense chips before setting himself ablaze. The crowd that gathered around him, most of whom shared Faru’s faith and understood the spiritual meaning of the act, were reportedly “full of grief and admiration.”

I have no doubt in the accuracy of those reports, but I understand why it is so easy, particularly for those of us in the contemporary west, to still miss the meaning behind these actions. Self-immolation is, at its core, a provocation. We see a human being on fire and our instinct is to save them, to rush over and stop the flames. The request of the committed self-immolater, in turn, is to ask us to notice that instinct, that part of us that sees an obvious act of suffering and wish that we could stop it.

There is a profundity in that reflex to help, to douse the flames in water. It points to the part of our heart and our soul that recognizes that every life is precious, that knows that there is nothing natural about war and suffering, that remembers that at the core of our being is a desire to keep other humans safe.

The dilemma is that the world as it is—the one built on domination and separation, the one that asks us to hate and fear one another, the one that claims that it is bombs and guns and retribution and punishment that makes us whole— relies, for its perpetuation, on us tamping down that particular part of our heart.

And so we see the human being on fire and are tempted to view their last act as one of escape and retreat rather than connection and outreach.

There has already been speculation, in the hours after Bushnell’s death, about his mental health. It’s telling that, while Bushnell’s livestream shows him calmly explaining his actions, and while his friends and family members remember him for his kindness and joviality, the police report claims that he was in “mental distress.” It’s even more telling that one of the two officers on the scene pointed their gun at him as the fire engulfed his body.

What do we see in the flames?

Do we see helplessness and nihilism? Do we assume that the activist in question was at the end of their rope, that they have given up on humanity?

Do we see them as a threat, as somebody who is unhinged, outside the boundaries of polite society? Do we expect law enforcement to deal with them the way they deal with all human beings who’ve been deemed expendable and dangerous?

The human being on fire is heartbroken but hopeful. They’re not hopeful for themselves, but for what the rest of us can build for and with each other when we resist the impetus to turn away from suffering. They believe that our hearts are muscles, and even when muscles have atrophied, they can still be strengthened anew.

The empire, in turn, is rooted in hopelessness. It has no language of caring, just force. And so it has no response to the human being on fire except to point a gun at the flames.

I have no plans to self-immolate, nor do I encourage anybody else to do so. I believe that the work of building a better world will take all of us. We need each other: here, on Earth, in these bodies, mourning and struggling and rejoicing together. But I am a pacifist, as well as a practitioner of nonviolent civil disobedience. As such, I understand that being unwilling to take somebody else’s life is not the same as being unwilling to put your own at risk for the sake of justice and humanity.

The profound call, in moments such as this, is not to follow the literal steps of Aaron Bushnell or the anonymous activists who recently died protesting wars in Gaza and the Congo, but instead to do everything in our power to ensure that we fulfill the hope inherent in their sacrifice. Most directly, of course, that requires us to put our voice and our bodies on the line in opposition to wars being fought— directly or indirectly— in our name. More broadly, though, they call us not merely to shout down empire, but to do so in a way that mirrors their immaculate love and their all-consuming belief that our hearts are larger than we pretend that they are.

When most of us think about self-immolation, the image in our mind is that of the Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức, who killed himself in protest of the U.S.-backed Diệm regime’s persecution of his fellow Buddhists. While a great deal of Đức’s ongoing fame is due to the power of Malcolm Browne’s iconic photographic of the stoic monk engulfed in flames, the most powerful elements of that story took place largely off camera. There was, for instance, the crowd of thousands of supporters who encircled him, many of whom lay down in front of fire trucks in order to prevent them from extinguishing the flames, collectively saying that while the impetus to care was correct, their help was needed elsewhere.

And then, of course, there is the matter of Đức’s heart, and the fact that the rest of his body was twice burned to ashes (first in the act of self-immolation, then in a later Buddhist ceremony) it remained fully and miraculously intact, defying all scientific explanation.

Diệm’s regime didn’t survive.

Đức’s heart did.

An everlasting reminder.

Empires will fall.

Bullets and bombs will never keep us safe.

But our hearts. Oh, our hearts. When opened up. When directed fully and completely outward towards one another. When placed fully at the center of our lives and politics. Our hearts are indestructible. Our hearts will live forever.

End notes:

-Continue to take action for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza.

-Support those impacted by the ongoing war in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

-For more on Bushnell’s protest, I loved this piece from

. I’m also deeply grateful for the work of Talia Jane, the movement journalist whom Bushnell trusted to share his story. Both deserve your support.-Speaking of support, I am forever grateful for all of you for keeping this space going. To be very clear, my hope is that if money is tight you prioritize Gaza and Congo relief efforts as well as mutual aid efforts in your community. For those who have the means, though, you can help me continue doing this work by becoming a paid subscriber, sharing this piece with your friends or pre-ordering The Right Kind of White (or requesting your local library purchase it).

This: “The empire, in turn, is rooted in hopelessness. It has no language of caring, just force. And so it has no response to the human being on fire except to point a gun at the flames.”

How can we be the opposite of the hopeless empire? I want to live that every single day.

Oh my heart.

"But our hearts. Oh, our hearts. When opened up. When directed fully and completely outward towards one another. When placed fully at the center of our lives and politics. Our hearts are indestructible. Our hearts will live forever."