White Fight (Part Two)

White Liberals and Leftists: "In this house, we believe whatever we need to believe as long as somebody, somewhere assures us that we're not like the others."

Roxane Dunbar-Ortiz, a sixty-year veteran of just about every significant American activist movement, tells a story about moving from Oklahoma to San Francisco in the early ‘60s. Growing up in a poor, White community in Oklahoma City, she desperately hoped that the Bay Area would offer deliverance from the closed-mindedness of her home (as a student at the first all-White school in the state to be integrated, she saw plenty of examples of her fellow working-class Okies behaving badly). Here’s how, decades later, she remembers the first moment she excitedly walked up to a table of white progressive activists in her new home.

“I fingered a flyer on the table that asked for donations to send freedom riders to Mississippi to protest segregated interstate transportation… They also had a sign-up sheet for volunteers. How I wanted to sign!

Suddenly, I heard my voice asking if they were going to talk to poor whites in the South. They seemed stunned by the question, perhaps thinking I was joking. But, my surely terrified face and trembling hands must have made clear that I was serious, and that I was myself one of the poor whites. Immediately, I wished I could take back the question and start over. Then, one of the young men said, “No!” and added that they weren’t recruiting them either.

It took several years before I tried to get involved again— only after I had successfully gotten rid of my accent… and driven the working-class Okie girl underground.”

From Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels and Black Power

Last week, I wrote about White conservatism’s extremely successful fifty-year project to mobilize its growing, cross-class base of White people against a surprisingly durable boogyman: judgmental White progressives. If you didn’t read it and you’re wondering what my thoughts are about a cynical effort to reduce millions of Americans’ understandable desire to feel seen and heard within the body politic to the lowest common denominator of slights and resentments… well, I’m against it! It bums me out!

Here’s another thing that bums me out: When a cynical political project orchestrated by one group of White people is enabled at just about every turn by the mindsets and preoccupations of a second group of White people! Yes, I’m going to criticize White progressives now, which I recognize is both predictable and well-trod terrain. As a Central Casting White Leftie, I know full well that there’s nothing we love more than a good struggle session. In the interest of not falling into the trap of self-righteous flagellation for the sake of it, though, let’s lay out some caveats.

First off, I am not just any White progressive. I come with the whole sampler platter of privileged identities on my plate (I’m a cisgender dude! A straight one, at that! And I have enough money in savings that I just paid for an unexpected car repair!). It is extremely easy for me to sit here and tsk tsk fellow White Liberals or Lefties for cocooning themselves from our skinfolk with more retrograde viewpoints. None of those belief systems include any fundamental attacks on my humanity! That isn’t the case for White women, for trans and non-binary White people, for Queer White people. So, while I don’t feel that this is a “Just Be Nice To Your MAGA Aunt” piece, if you find yourself wading through this and saying “ok that’s easy for that dude to say, but I need to maintain a certain set of social/political boundaries not out of some abstract sense of political obligation but for my own protection and dignity”… fair enough! I hope there’s something interesting still here for you, but I understand if not!

Secondly, I think it is extremely easy for a piece like this to just devolve into tired Boomer bashing. This one is tricky. On one hand, as was the case with the evolution of White conservatism since the ‘70s, I do believe that the White Left is stuck in a rut that began a couple of generations ago. On the other hand, it’s important to put the range of choices available to 1960s and 1970s White progressives in context.

Before there was a New Left, there was an Old Left— a consortium of labor unions and Civil Rights activists and Reds of various hues and intensities. Whether or not remnants of the Old Left could have transformed American society under stable conditions will never be known, however, because conditions in Mid-Century America were anything but stable. By the end of the 1950s, a one-two punch of Mccarthyism at home and the stain of Stalinism abroad took care of the Left as a political force. In the meantime, the economy and demographics of the country were transforming, and rapidly.

As much as I revere David Harvey, I’ll save you the full, accurate-but-dry Fordist to Post-Fordist play-by-play here, but you know the story even if you don’t know the story: Over the middle of the century, because of globalization and automation and a whole bunch of relatively affluent White people running around buying refrigerators and having babies, Western countries (particularly the U.S.) moved from an economy organized around producers to one organized around consumers. Global capital found that there were higher profits to be had by pushing production off to increasingly less unionized corners of the world, and so America evolved into a place where blue AND white-collar work was increasingly consolidated in the big, vague, non-making-things “service sector.” A wild but telling example: By 1960, the United States was the first country in the world that had more students than farmers. By 1969, it had three times as many students as farmers.1

That’s to say, 1960s activists can’t be blamed for not successfully building off of the movements that came before them (those movements had either disappeared or were built for a version of America that no longer existed). What’s more, any judgment of 1960s-1970s activists should take into consideration both the intense level of state repression and dirty tricks (COINTELPRO, MK ULTRA) as well as the collective trauma of assassination (MLK, Malcolm X, RFK, etc.) and state violence. For all the “winds of change” vibes that may or may not have been in the air, it was actually a pretty harrowing time to try to make change.

With all that said, it is notable and not surprising that the mid-century social change movements most centered on community building, collectivism and cross-generational care were those led by Black, Brown and Indigenous people. It’s not that there weren’t generational or class divides present in the Central Valley Farmworker’s marchers or the American Indian Movement’s Wounded Knee Occupation or the Panthers’ Free Breakfast programs, but in each of those cases, there was a guiding principle of taking care of and welcoming as many members of a given community as possible.2

By contrast, White-led New Left movements were, from their inception, more deeply rooted in a politics of individualism and exclusivity. Having identified (either in the Bomb or the Cold War or the Jim Crow South) a rot at the heart of middle-class White American society, the (sometimes implicit, sometimes explicit) goal of the young White Left was to declare a clear, tangible separation from Bad White Americanness: from their parents, from less-educated Whites, from their hometowns. Influential essays like Norman Mailer’s The White Negro (and a similar but even more problematically title tome by Jerry Farber3) said the quiet part here out loud, positing that, either by force of their hipness/ability to critique the system and/or their alienation from their parents, that radical White youths were essentially the same as Black people (that is to say, very cool but very oppressed by the exact same enemy— namely less cool White people).

Not surprisingly for a group that was trying to maintain its distinction from other White people, hip young White radicals in the 1960s made initial stabs at cross-class, cross-generational partnerships, but abandoned them for shinier, more gratifying objects. Early, promising experiments in working-class organizing (like SDS’ organizing work in Chicago’s largely Appalachian Uptown neighborhood) were shelved, for example, for large-scale anti-war marches. In the meantime, even when Stokely Carmichael kicked Southern-bound activists out of SNCC and told them explicitly to join organizing efforts underway in the rural White South, few would-be freedom riders actually took him up on the offer.4

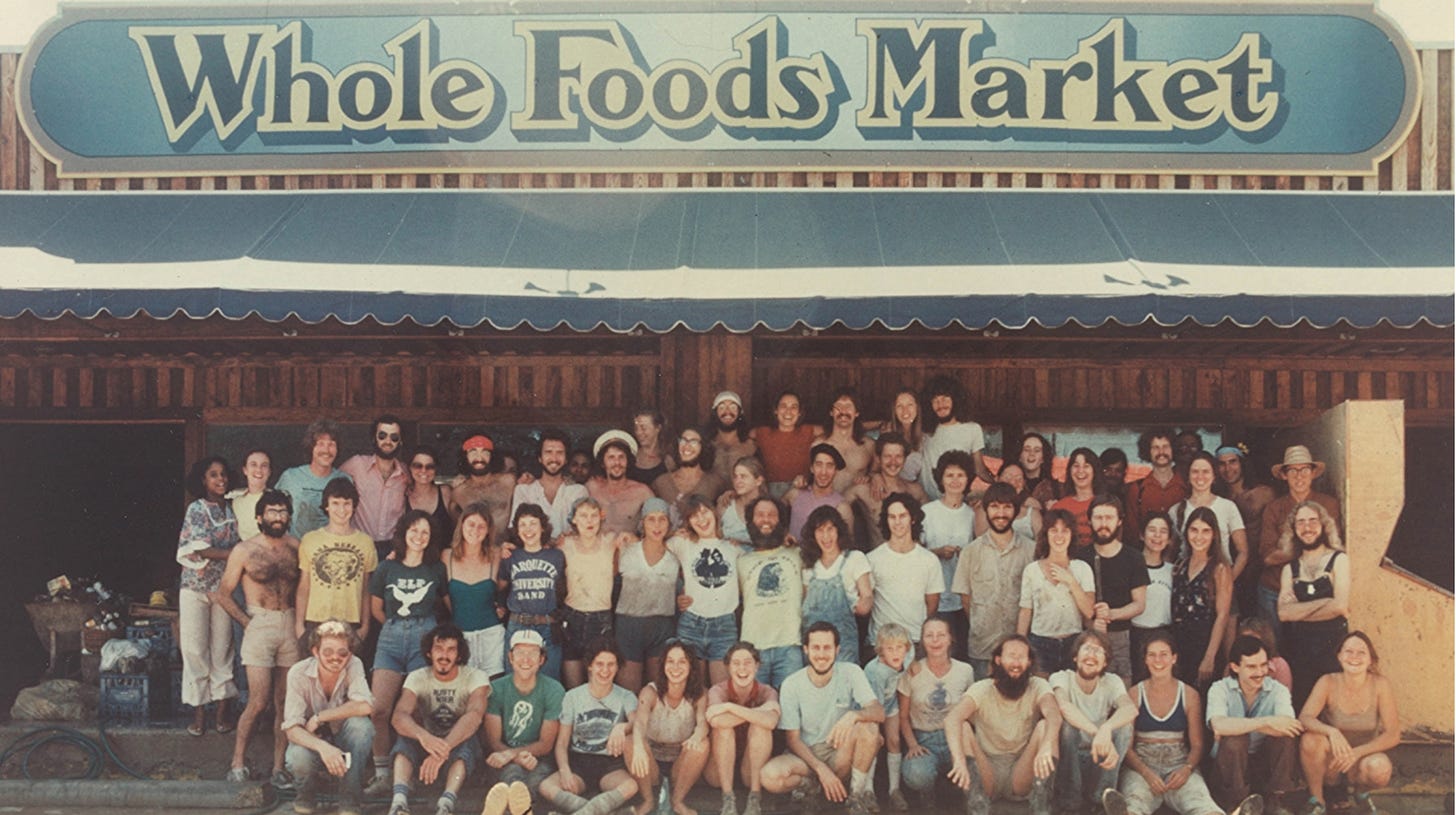

As the ‘60s gave way to the ‘70s, the politics of the White Left became increasingly indistinguishable from the more individualistic and hedonistic psychedelic wings of White youth culture (“If it feels good, do it,” et al.). What was once at least ostensibly about collective politics became about culture and consumption.5 Even the political movements that emerged as a corrective for the New Left’s missteps (such as the more radical feminist movement that sprung up partially in response to the male-dominated Left’s misogyny), trafficked in rhetoric that reified the (often White) individual, rather than the pluralistic collective (see for example: “My body, my choice”). Where there was collectivism, it was directed towards projects for the young radical community themselves— urban food co-ops and bookstores, rural back-to-the-land communes.

Again, there is some fairly understandable context for all this! This was a generation that was very truly being sent off to die by its parents, that did have to watch as one potential figure of deliverance after another was shot down in public. The real tragedy wasn’t what track we got ourselves on in the 1960s, it’s how steadfastly we stayed on that track afterward.

By the end of the ‘70s, Madison Avenue had fully mastered the art of hip, pseudo-radical cooptation: aping the aesthetics of an already consumeristic counterculture to sell Volkswagens and soda. The one-time counterculture itself had gotten pretty good at marketing various personal pathways of liberation to itself— be it in the form of gurus or Human Potential Project meditation retreats or whatever new product the Whole Earth Catalog was hawking that month. It isn’t that many of these new areas of interest were bad— I personally believe that we should all buy more solar panels and have more therapeutic breakthroughs on the beach! The gurus I can take or leave, but a lot of the other stuff is good! The risk of making all that the center of Left culture and politics though, was a further codification of the idea that progressivism was less about welcoming as many people as possible into a collective political project, and more about buying or doing or saying the right things to establish your cultural capital with other progressives.6

The reason why I keep backpedaling every time this sounds too much like Boomer-bashing, is because, as a now very-middle-aged 1981 baby, this may have been the political and cultural world that I inherited, but my generation has had an entire half-lifetime now to imagine a different path and… well, we never quite got around to it. Take, for example, the trends of Left-liberal White engagement in various cross-racial solidarity projects. During the Obama administration, there was very little collective White uproar about our country’s dehumanizing immigration policies. Black Lives Matter protests in Ferguson and Baltimore and Baton Rouge were still majority Black. After Trump’s election, belief-affirming yard signs started popping up in White progressive enclaves, “kids in cages” became a progressive mainstay rallying cry and White people began flooding Black Lives Matter protests. As the UPenn Professor and Civil Rights Activist Mary Frances Berry noted when asked to explain the paler hues of most 2020 BLM marches, “this whole protest, writ large, is a protest against Trump.” Yes, we cared about these issues, but we also cared about the signal. We weren’t like Trump. We weren’t like the Trumpers. Our care was the proof.

While the White right has spent the past four decades consolidating their political power (starting at the precinct level, winning state legislatures and then…well… creating the political map that currently flummoxes us), the Left, which had already become obsessed in the 1960s and ‘70s with the power of being represented culturally, leaned more heavily into producing and consuming culture. The Reagans and the Bushes of the world may have kept winning the White House, but we had punk rock and a heavier percentage of late-night TV political jokesters.

This all creates a deeply cursed dual siege mentality on the part of both sides of White America (Charlie Warzel coined not one but two exceptional phrases for something similar to this: “culture war doom loop” and “Möbius strip of grievance”). American liberals, including (often most vocally) White American liberals, feel at siege because they (quite accurately) look at how Mitch Mcconnell, and the Supreme Court he created, basically get to run the country regardless of which party is in power. American conservatives (again, especially the White ones) turn on the Oscars and hear that this or that star of a huge blockbuster said this or that liberal thing and then go to work the next day and learn they have to go to a White affinity group, which then makes them feel like they’re actually under siege. White liberals/Leftists then respond to their version of the siege mentality by doing what we’ve been doing for decades: throwing out one signifier after another— a land acknowledgment here, a move from “POC” to “BIPOC” there- that might better ensure aren’t mistaken for our more loathsome skinfolk. White conservatives, in turn, respond by further destroying American democracy (this year’s big innovation, in case you forgot: we’re doing attempted coups now!).

There are a lot of losers in this particular stand-off: American democracy, for one; any hope of a more liberating future envisioned and led by Black, Brown, Asian and Indigenous young people for another. The winners, of course, are irony as a general concept (since this entire loop requires both groups of Americans with the most racial power and privilege to constantly obsess with how we’re losing) and, most of all, corporate America. There is pretty much no better and more sustainable political arrangement for American big business than a (White) Left that dictates consumer culture and a (White) Right that controls politics. It means lower marginal tax rates AND higher annual revenue when your ad guys plop Colin Kaepernick in a campaign or come up with an over-hyped tagline (“True Name”) for something your industry should have been doing as a default (in this case, letting trans people put their chosen names on credit cards without a lot of fuss).

It is a mess, this cycle! And, as I noted this week, while I don’t think anybody in America needs saving from White people, it’s pretty clear that all this wild shooting at one another is profoundly gumming up the works of collective forward progress. And yes, I have suggestions, for those of us on the White Left, of what this means for us (no, it doesn’t mean we all have to go to a MAGA diner in Pennsylvania and look concerned and empathetic). If you’ve been reading this newsletter for a while, you have a decent sense of what some of those ideas are. And I promise, in subsequent weeks, I’ll keep highlighting organizers who I think are breaking the cycle.

None of that matters, though, without the choice point: Why do you care about politics or racism or inequity? Is it about the country you believe we all deserve, or the reputation and social networks you most desperately want to maintain? What if the actions that could most help the better world didn’t get you any personal kudos, didn’t lead to a world of radical Black friends who assured you, whenever you secretly wanted to hear it, that you weren’t like the others? If you’re a White person whose identity means that only a limited number of spaces are safe for you, how are you making it more likely that others are welcome there with you? If you’re the kind of White person whose safety is never in question, then what and who are you running from?

We’ve got a choice, my friends. We could all run towards a better world together, or we could keep desperately running away from our shame. There is no shortage of personal reasons to choose the latter. The problem is, we’ve been down this road before. We’ve been on it for fifty years. And I don’t know anybody who’d say in good faith that it’s leading in the right direction.

This week’s song: Ace Ball “Country Boy At College”

That statistic comes courtesy of Todd Gitlin’s The Sixties: Days of Hope, Nights of Rage, a book which I highly recommend even though it contains more detail about extremely boring SDS meetings than I ever imagined I’d read willingly.

If you’d like a non-hagiographic but still appropriately appreciative articulation of what made these movements particularly special and grounded, check out Margaret and David Talbot’s By The Light of Burning Dreams.

I’m not linking to the Farber essay because it’s title is a racial slur and it’s a bonkers piece of writing regardless, but if you know you know.

This particular exodus of would-be freedom riders is what led the indefatigable Anne Braden, to throw up her hands and complain (about the White radicals) “they just don’t like White people! You can’t organize anybody if you don’t like them!”

Want a contemporaneous account of this that’s super smart? check out Daniel Bell’s The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism

Cultural capital! That’s a Pierre Bourdieu concept! He rules. But you don’t need a French sociologist to tell you that’s a thing we humans do, namely obsess over the cues that will establish our membership in an in-group. I mean, that’s painfully familiar to any of us who were ever teenagers, right? Regardless, thanks to Bourdieu for all this.

So good, as always. And this line, above all: “ There is pretty much no better and more sustainable political arrangement for American big business than a (White) Left that dictates consumer culture and a (White) Right that controls politics. ”

Dude, you are ready to teach a movement history course and I want to take it please! Could this be a Barnraisers elective?