Blinded by the White

On Michael Oher, the ubiquity of savior stories, and why I didn't want to write about The Blind Side

Top Notes:

Hey there! Welcome new readers, especially all of you who are here thanks to the Work Appropriate podcast with Anne Helen Petersen. I hope you enjoyed listening to it as much as I enjoyed recording it. Also, as an aside, if you are on Instagram and aren’t following Anne Helen’s comprehensive guide to sorority rush season (check out her stories), you are in for a treat— its honestly some of the best non-snarky, deeply contextualized collective cultural analysis you’ll find anywhere (and for the record, both Leigh Anne and Collins Touhy were Kappa Deltas at Ole Miss).

Secondly, this wasn’t the essay I planned to write this week. I also can’t decide if it counts as a bonus issue in the “10 Movies, 10 Series of Whiteness” series or not. Who doesn’t love eleven movies in a top ten list? It’s like how Big Ten Conference has roughly 45 teams now and the Pac 12 is just two colleges in a compact car (my apologies to non-college-football-following readers; I promise there will be no further dumb conference realignment jokes).

What I do know is that I’m very glad you’re here, and that, as always, this place wouldn't exist without paid subscribers. Have you been on the fence for a while about subscribing? No better time to make the jump than the present (says who? well me, and I’m biased, but still).

Finally, stay tuned for a bunch of fun announcements coming next week [there will be book news (!!), as well as the enrollment launch for the fall Barnraisers cohorts (!!)]. Get hyped.

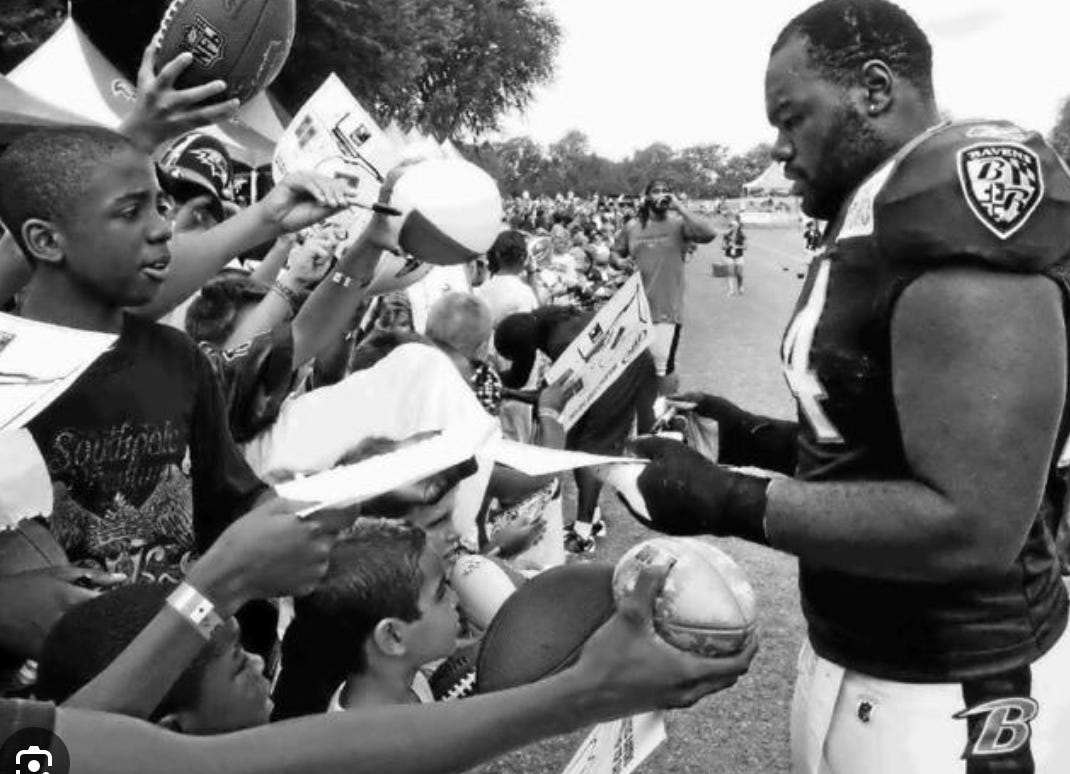

Michael Oher is a father, an author, and a former NFL star. Most famously, though, he was the subject of the 2009 film The Blind Side, which purported to tell the story of how Oher, then a Black teen from a Memphis housing project, was adopted by a benevolent White family, the Touhys.

Yesterday, the news broke that Oher has filed a petition against the Touhys in a Tennessee court. The petition contends that the Touhys lied about his adoption and instead tricked him into signing a conservatorship agreement, allowing them to profit from his story. The Touhys— who objectively did become famous and rich(er) due to their association with Oher— deny the charges.

This isn’t the first time that Oher has critiqued other people’s versions of his life. The Blind Side, a film that won Sandra Bullock an Academy Award, depicts Oher as a lovable but helpless brute who, previous to meeting the Touhys had never seen a bed, barely knew how to read, and did not understand that the game of football involved tackling. Unsurprisingly, the real Michael Oher has been vocal about his concerns with a film that depicts him as merely being an empty vessel into which White benevolence could be poured. It is, however, the first time that he’s taken the Touhy family to court.

Court cases serve many purposes, but one of their most powerful functions is narrative. Two sides present their story. The judge bangs their gavel. One of those two stories is validated and the other one isn’t.

When I first started my current summer series on movies about Whiteness, I considered choosing The Blind Side, but ultimately decided against it. It’s not that it doesn't offer a deep well of unexamined Whiteness, but there are plenty of other White savior movies, as well as plenty of movies about the intersection of race, gender and class in the South.

Even more than that, though, I was worried that critiquing the movie would be like shooting fish in a barrel. This is a film that first introduces Michael Oher by listing off his physical attributes in a way that sounds eerily similar to a nature documentary. For the rest of the movie’s run time, he mostly just ambles about like Charlie Brown on a bad day: sad, helpless and frequently wet. He is all slumped shoulders and weary ennui. And with good reason, as the movie reminds us repeatedly. He was failed by his family, by the school system, but most of all by the absence of rich, caring White people in his life.

Then, the clouds part. On one magical, extremely cold night (which in Memphis means it was likely 72 degrees out), Michael is spotted, mid-amble, by Leigh-Anne, the dewy-eyed-but-feisty Touhy family matriarch. She takes him home, removes roughly 500 throw pillows from a comically overstuffed sofa and, slowly but surely, a brand new Michael Touhy is unlocked. Leigh Anne teaches him how to read, play football, and receive a mother’s love. Suddenly, Michael’s life is full of suburban creature comforts, banter with The Touhys’ precocious elementary aged son and heartwarming moments of baby-deer-style discovery (books! family dinners! furniture!). Meanwhile, Leigh Anne walks in and out of various Shelby Country conference rooms, removes her sunglasses, and fights righteous Mama Bear battles for her newly beloved big Black son. There is talk about how “I didn’t change his life, he changed mine” and then, in the movie’s climax Michael rewards her benevolence by fighting for her— physically protecting Leigh Anne and the Touhy’s teenage daughter from the lecherous threats of dangerous Black men from the projects.

Yikes.

You can see why I resisted writing a Blind Side essay. This is not subtle stuff. The movie has already been critiqued quite effectively. As Michael Oher himself has pointed out repeatedly, that film was never his story. It was always about the Touhys—it was the version of events that flattered them the most, that offered them riches and fame, that saved their souls.

Like Leigh Anne Touhy, I’m a White story teller. In a previous life, I had to raise money for schools and education nonprofits. I’ve told a fair number of White savior stories— both my own and others. I’ve told stories about White teachers loving their Black and Brown students so much that they tutored them after hours at McDonalds. I’ve told stories about loving my own Navajo students so much that I drove hours across potholed reservation roads to visit their homes. I’ve told stories about meteoric rises in test scores, about kids who, like Michael Oher, met a caring White person and then, like magic, were whisked away to charmed lives in exotic locales like Oberlin College or the Human Resources office at Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance.

It’s not that I ever told any lies. But just like how you don’t need me to critique The Blind Side for you, you don’t need me to point out what characters don’t have any agency, humanity or interiority in those narratives. The problem with those stories is self evident. Though they pretend to be about Black and Brown people, they actually center the White narrator. We are the heroes. We are the only ones depicted as being fully human. Thank God for us.

That’s the accurate (and popular) critical analysis of White savior stories. But it’s still not the full truth.

As I read about Michael Oher’s lawsuit and rewatched The Blind Side yesterday, I realized that the White characters in savior stories aren’t real protagonists either. I mean, in a pure, classic literary sense, I suppose they are. But in those sorts of stories, none of the characters on the page actually matter.

What matters— when we repeat fables of White salvation— isn’t what’s told, or even who is doing the telling, but who hears it. The important character is the audience. It’s only in the receiving that these folktales have any meaning. The content isn’t important. What’s interesting is what the story teaches the audience about their world, how it makes them feel, and (if they’re White) what fears or angst it assuages.

In my case, the only characters that mattered were the philanthropists or elected officials to whom I was pleading my case. The real point of my stories wasn’t about how I was a great caring teacher. I wanted my audience to believe that if they give their money to this or that program or school, then they got to be the real heroes. What’s more, if I told my story well, they’d believe the system that enabled their wealth and power could carry on unabated. They’d rest easy knowing that their position in life was justified. All they had to do was sign the check and any guilt, doubts or cognitive dissonance would immediately disappear.

In the case of The Blind Side, a nakedly racist movie that came out during the Obama Presidency, the protagonist that mattered wasn’t actually the Touhys, it was the million of audience goers who flocked to see it. At the time of its release, The Blind Side was the highest grossing sports movie of all time. It was one of the rare instances where a film earned more money from its second and third release weekend than its first— a classic sign of a word-of-mouth hit. The Blind Side told its (mostly but not solely White) audience not just that the Touhys were a very good family with big non-racist hearts, but that the core righteous fabric of our country was still intact. It whispered reassuringly that if a White mom could love a big Black boy that hard, then the center had in fact held. We had made our way to the mountaintop, together.

There is a comfort, for White people, in hearing savior stories. But there is also a comfort— particularly in a post Trump, post George Floyd, post ubiquitous white collar DEI trainings world— in critiquing them. Just like how, in 2009, the cultural zeitgeist still allowed White people the narcotic comfort of films like The Blind Side or The Help, so too do good progressive White people in 2023 turn to the great sport of self-satisfied finger pointing. And what a great villain we have in The Blind Side. Leigh Anne Touhy is a loud, wealthy, self-promoting Southern woman. Heck, I bet that she’s asked to speak to a manager or two in her day. If ever there was an easier target for a bookish progressive White man who writes on the Internet, I haven’t found it.

I have no reason to believe that Michael Oher’s claims aren’t accurate. The Touhy family are likely not just self-aggrandizing storytellers, but actual con artists. They deserve critique. They deserve accountability. Michael Oher deserves whatever will provide him more peace and justice.

Whatever happens in that trial, though, there will be no shortage of commentaries about how the Touhys are bad White people and The Blind Side is a bad movie. And while those commentaries will come from a wide diversity of voices, many of the smuggest will come from White people. White people who hated The Blind Side when it was first released will compliment themselves on their trenchant wisdom. White people who loved The Blind Side when it came out will testify just as loudly as to their contemporary hatred. There will be back-patting. The Touhys will likely suffer some degree of temporary embarrassment (before being reclaimed as cancel culture victims). Sandra Bullock may have to put out a statement. And then, the news cycle will keep on moving forward. We will have once again successfully made a complex, knotty story of systemic injustice into a morality tale about two-to-three individuals.

The irony here is that Michael Oher is an offensive tackle. As the opening monologue of The Blind Side reminds us, his is a particularly important role on the football field. While everybody else is watching the ball, he pays attention to what would otherwise go unnoticed— the subtle movements of defensive tackles, the threats that can truly do damage. His is a job that rewards those who don’t get distracted by loud, shiny objects or miss the forest for the trees. His is the kind of skill set that often goes ignored at moments like this.

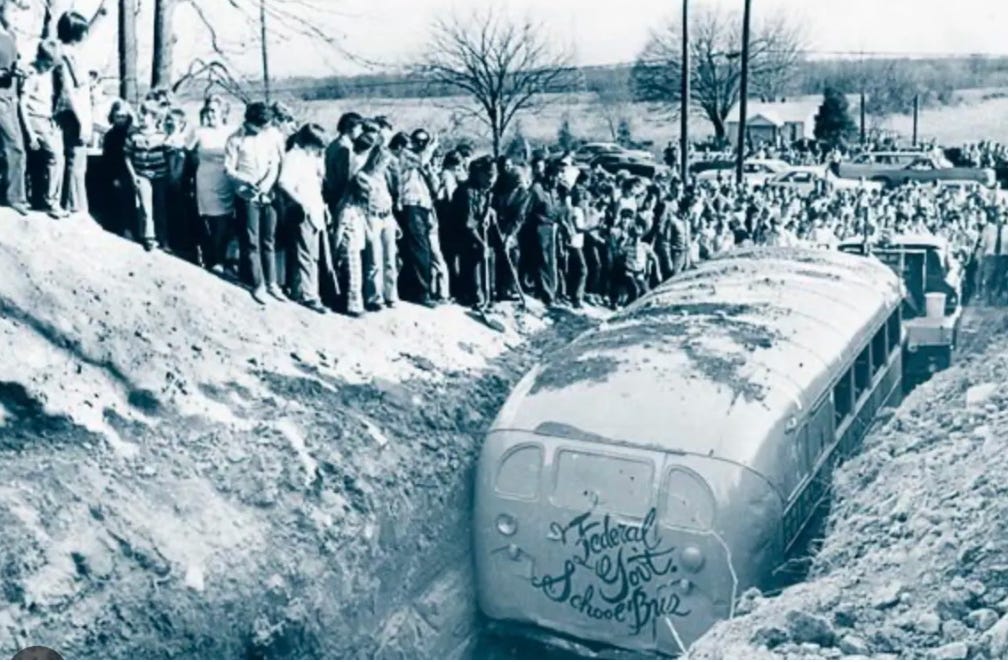

Oher’s lawsuit against the Touhys won’t be the first prominent court case with a connection to The Blind Side. In 1976, a Black Memphis mother named Inez Wright was the named plaintiff in a class action case against both the United States Treasury and thousands of private schools across the South and the Midwest. Wright’s argument was that those schools— the infamous “segregation academies” that sprouted up like wildflowers in the wake of Federal school desegration— were by their very nature exclusionary and shouldn’t receive tax exempt status.

The named defendant in Wright’s case was the Reverend Wayne Allen, whom the New York Times described as the “ebullient and forceful” pastor of Memphis’ East Park Baptist Church. In 1971, Allen’s congregation— which included some of Memphis’ richest White families— decided to get into the private school business. They called their new creation Briarcrest and dubbed their athletic teams The Saints.

To this day, Briarcrest still loudly proclaims that the school’s founding had nothing to do with desegregation, but merely reflected a spontaneous desire to spread the good word of Jesus Christ in East Memphis. How miraculous, then, that almost immediately after the school opened its doors, thousands of White families who would have been zoned or bused to majority Black schools felt the call of the Lord to have their children become Briarcrest Saints.

Speaking of stories, the Briarcrest website’s “history” section is an absolute master class of narrative construction. Here’s what the saintly storytellers of Eads, Tennessee have to say about the Wright case.

In 1978, the IRS decreed that all private schools that were created after 1970 or had increased in enrollment since 1970, must have a significant percentage of minority students enrolled in their schools or that these schools would lose tax-exempt status. The resolution was designed to penalize the so-called “white flight” schools. Even though Briarcrest was founded based on non-discrimination and had worked hard to recruit minority students and employees, the IRS specifically mentioned Briarcrest Baptist School as an example of schools that would be affected. Briarcrest requested that other area private schools join them in fighting this resolution and defending their own non-discrimination policies, but no other schools joined the effort. Briarcrest took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, and in 1984, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Briarcrest. The IRS resolution was struck down, ultimately benefiting all private schools.

Not all heroes wear capes. Some heroes are brave enough to do the dirty work that all the other segregation academies were too afraid to do— to stand up in front of the Supreme Court and declare that they had nothing to apologize for, no reason for shame, and definitely no reason to cease to exist. Thousands of schools could have made that argument, but Briarcrest was the only one to step up. And since their lawyers won the day, it was Briarcrest that made possible the full institutionalization of America’s most nakedly racist educational institutions. Thanks to Allen v. Wright, it was official. Segregation academies would never be a mistake. They would always be accepted as part of the firmament of their communities, as natural as the cicadas on a summer night.

It bears repeating. Court cases serve many purposes, but one of their most powerful functions is narrative. Two sides present their story. The judge bangs their gavel. One of those two stories is validated and the other one isn’t.

The Supreme Court issued its Allen v. Wright decision on July 4th, 1984. Today, Briarcrest is the the largest network of private schools in Tennessee. It has taught multiple generations of Memphis’ (mostly) White elite. And, of course, it has had its moment in the Hollywood spotlight. Where else in Memphis would Leigh Anne and Sean Touhy have sent their children? Where else would their not-actually-adopted-son Michael Oher have dominated the gridiron? Where else can the good people of Shelby County find salvation?

Let’s go Saints.

The myth of the Touhys may finally be dead, but Briarcrest (and the thousands of Briarcrests across the country) will live forever. They won’t be the protagonists of any easily critiqued White savior stories. They won’t get the scrutiny we give to the loud, brash White women whose misbehavior we notice more than the White men who operate in the shadows. But make no mistake about it: They’re the reason we tell those stories.

One by one, none of the feel-good fables are ever about the kid who made it, nor about the surrogate parent/teacher/church/social worker/mentor who just loved them so much. They’re about how the rest of Whiteness can carry on unimpeded. They’re about how we don’t have to feel guilty when we turn our nose up at our local public school. They’re about how of course it’s ok that we move heaven and Earth to send our kids to whatever private academy or magnet school or suburban citadel promises to work its hierarchy-sustaining magic in our favor. They’re about how the shape of our cities, the shape of our country and the shape of our inheritances (for many White people, both figuratively and literally) are mere inevitabilities.

In Memphis, those stories aren’t about what enabled Michael Oher to get into Ole Miss. They’re about how “getting into Ole Miss” is a goal worth reaching for in the first place. They’re about how Ole Miss and Auburn and ‘Bama, with their Old South Cosplay—Student Government Machines and Tailgates in the Grove and Tik Tok Famous Rushes—are as inevitable as Briarcrest. In progressive Oakland and Seattle, those stories are about how their private schools and large foundations are all good now because they make “proudly unapologetic” social justice statements on their websites and quote Audre Lorde when rolling out their vacation policy memos. In Minneapolis, they’re about how the Target Corporation isn’t like those other companies because they sell shirts that say “Black Girl Magic” and “Pride is Fierce.” Over at the Brooklyn socialist happy hours, they’re about how all it takes to build the worker’s paradise is the ability to scoff at how all the other White people are dumb, ill-informed and thoroughly uncool.

I hope that Michael Oher wins his court case. I really do. I hope that in the future we tell fewer stories like The Blind Side. But even if our critiques get wiser and more voluminous, I don’t have a lot of faith in that happening. Regardless of how many diversity trainings we attend, White people will tell those stories until we’re ready not merely to poke fun at them individually, but to examine what they do for us, what gift they provide the larger project of Whiteness, and why we’re addicted to the cheap magic trick of collective forgetting.

End notes:

Song of the week:

I’m sure that it’s just an oversight that when Memphis rapper Yo Gotti wrote his 2006 hit “That’s What’s Up,” (a song that namecheck multiple Bluff City Icons) that he forgot to recognize Leigh Anne and Sean Touhy for being true heroes to all Black Memphians. Still a fun song, though!

I need to update the song of the week playlist, but in the meantime you can still listen to it, even if it is a few weeks out of date. You can find it on either Apple Music or Spotify.

The fact that there's a conservatorship at all that needs to be contested and from which Oher needs court permission to cast off is pretty damning of the Touhy's - it DOESN'T function as an adoption at all, so what WAS the purpose of it? Pretty obvious in retrospect sadly, and shame on the judge that approved it.

Thanks, Garrett, for reminding me of the practice of humility required to dismantle the white supremacy always lurking in my subconscious. Also, appreciated the section on segregation academies. I live in Iowa and we passed a school voucher bill this year so families can send kids to private schools subsidized by taxes. I went to public schools in the 60's and early 70's in the suburbs of Chicago and they were essentially segregation academies that we publicly funded because of redlining and white flight, so I can't judge families making the same decisions that mine did. I live in the Des Moines school district, with 30k+ students, almost 75% qualify for financial assistance for lunch. Your article has reminded me of my vague semi-commitment to attend school board meetings. I've learned by attending city council meetings regularly that showing up matters. Time to get those school board meetings on my calendar!