Pander! At The Rodeo

Kristi Noem's story of America isn't entirely wrong, but it sells us all short

Top notes:

You’ve probably caught on by now that this is the section where I gently encourage you to become a paid subscriber. And yes, that’s important. This may sound self-aggrandizing, but I think of this as a tiny experiment in mutual aid. I don’t mean the way mutual aid gets talked about too often these days (basically a fancy word for charity) but the actual idea of committing to a community, offering what you can to it and, in turn and being willing to ask for what you need. In my case, I’m offering what I hope is a thoughtful space and some decent writing. One of the many things I need to keep doing so is an actual income. If you can help out with that financially, great. If you can’t, thanks for giving in other ways (feedback, emails saying “hi,” resource sharing, etc.). Last week, multiple people gave me a good book recommendation! It all helps! And, as always, if there’s ever anything you need from me, let me know. garrett@barnraisersproject.org.

South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem wants you to know that she is just like you. She is a hard-working mom who’s had to dart from a late night at the office to cheer on her kids at a sporting event. She loves her new granddaughter, doesn’t suffer fools and will never say no to a cup of coffee or a Dairy Queen Blizzard.

She also, quite pointedly, wants you to know that she is nothing like you. She is not only a farm girl from a small town, but the living personification of a very specific image of Rugged American Westernness. She is destiny, manifest. She is John Wayne and Teddy Roosevelt reborn— with all the requisite stories of deer hunts and calf wrestling and minor acts of larceny on rodeo grounds to prove it1. She is also a former South Dakota Snow Queen, readily embodying every traditional White American female beauty standard (not to mention anti-feminist denunciation) expected of the office. In both cases, she knows her angles. She knows the power of presenting a very specific image. She hopes that you are watching.

Kristi Noem would very much like to be President. There is no other way to explain her regular appearances on Fox News and at CPAC, her ad buys in Iowa and New Hampshire, or the way she increasingly surrounds herself with national conservative operatives— including disgraced sexual predator and Trump loyalist Corey Lewandowski.

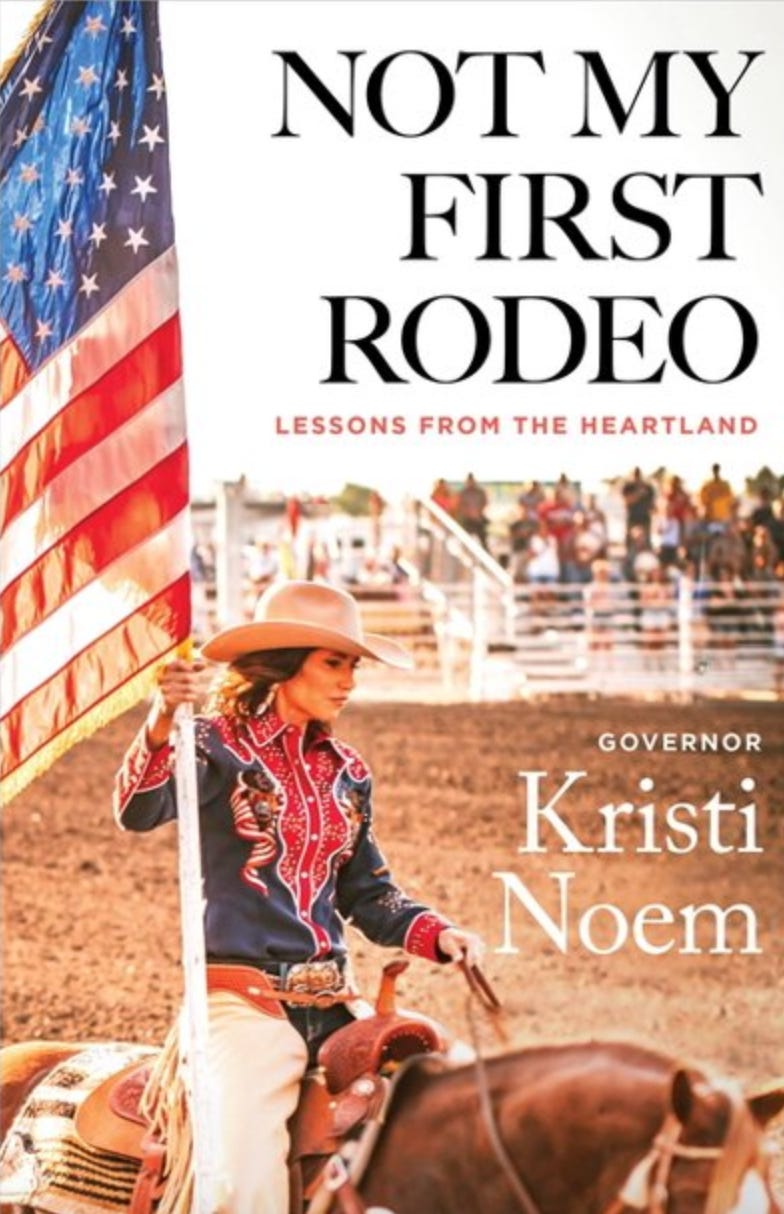

When you want to be President of the United States in 2022, there are certain stations of the cross that you must navigate. One of the sillier ones— perhaps even sillier than all of the various stunt foods you have to eat on camera at the Iowa State Fair— is that you have to write a book about how you love America unconditionally but also how America has lost its way and only you can save it. Noem passed that test earlier this year with the publication of “Not My First Rodeo: Lessons from the Heartland” (oh goodness, that title!).

Another test is that you have to not lose an embarrassing election in a winnable environment, lest you raise questions about the extent of your political magic.

Next week, Governor Kristi Noem may or may not fail that second test. She is in a tough re-election race against an amiable former teacher and state legislator named Jamie Smith. Modern South Dakota may be deeply conservative, but Noem has truly had to sweat this one out. Although Smith has much less name recognition (and far less cash on hand) than Noem, everybody who meets him (from both sides of the aisle) genuinely likes him. Meanwhile, Noem’s tenure as Governor has been marked by bitter fights within her own party, accusations of influence-peddling, and generalized fatigue about the fact that she clearly has her eyes on a shinier prize than you can find in Pierre.

That’s all to say that next week, we will know whether Kristi Noem’s Presidential aspirations have been dealt an embarrassing and potentially fatal blow, or if they are still alive and well. She will either be South Dakota’s Icarus (or, more accurately, South Dakota’s Scott Walker)— flying too close to the sun and forgetting her base— or she’ll get to prove her haters and doubters wrong with another convincing victory.

With her political future at a crossroads, it seems like as good a time as any to read Kristi Noem’s book.

I should probably explain myself here, as voluntarily reading “Not My First Rodeo” by Kristi Noem is not a normal way for anybody to spend their time, regardless of political persuasion. I have far more pressing concerns on my mind than a theoretical Post-Trump GOP horse race. I am, however, deeply interested in the State of South Dakota, and East River South Dakota more specifically— that huge swath of glacier-pummeled farmland where both Kristi Noem and my parents grew up. The single biggest lie in “Not My First Rodeo” is when Noem declares that Northeastern South Dakota’s topography is full of “endless rolling hills.” It is not. It would win a gold medal for flatness, if such an award existed. It is not the mythical West of the Black Hills. It is full of farmland and pheasant hunts and small towns connected by perfectly straight two-lane roads.

In Noem’s telling, though, Hamlin County, South Dakota is a Hollywood-ready land of heroic cowboys like her own father, a taciturn, John Wayne-quoting taskmaster fighting a one-man battle against the elements, an overreaching government and his own children’s age-appropriate weariness at being constantly forced to do farm chores. It’s a perfect origin story for a political autobiography, in that every single element makes complete sense as long as you don’t squint at it too hard. We learn that Noem’s family lived season-to-season, earning a living thanks solely to their own grit, determination and a steadfast faith in (I can only assume) an equally gruff and taciturn Scandinavian God. That story is true, as long as you fudge the size of their not-at-all-humble “Racota Valley Ranch” and ignore the millions of dollars in government subsidies that their operation has received over the years.

Norm would like you to know that the government has always been a thorn in her family’s side, except for the part where they cleared and colonized and Homestead-Acted the land one which their farm/ranch sits, subsidized their product, built and maintained the connective infrastructure they needed to send crops to market, etc. etc. etc. But those are easy critiques. We know Noem has an elastic relationship to the truth; it comes with the business she’s in. What’s more interesting isn’t whether or not Noem’s story holds up to scrutiny, but why she’d choose that story as a means to present herself to the nation in the first place.

This is the part where I admit that Noem’s isn’t the only South Dakota political biography on my nightstand. My parents grew up a couple of counties west of Noem. Their hometown, Doland, was also the boyhood home of the man who was, at one point, more synonymous than any other figure with mid-century American Keynesian liberalism: Hubert Humphrey, the Happy Warrior. Doland play a heavy role in the book I’m writing, and as such I’ve read three separate biographies of Humphrey, all in a quixotic quest to understand why small towns in Eastern South Dakota once produced passionate White champions for racial and social justice and now produce politicians whose major moral campaign is attacking trans kids. I’ve written a couple of pieces that touch on what I’ve discovered so far, but the digging continues.

Like Noem, Humphrey once told a lot of stories about the lessons he learned from his Father, Hubert Senior. The difference is, Hubert’s stories about Dad Humphrey, Doland’s town druggist, always situated their family as part of a larger community— one of farmers and small business owners and other Dolandites facing the threat of dust storms and big banks and robber barons near and far together.

And listen, Humphrey was also an overly ambitious politician, just like Noem. Surely he too was stretching the truth and buttering up his audience when he came back to town for a Centennial program in 1976, telling the Dolandites in attendance (my parents included) that he believed in the power of people to care for one another because that’s what he learned in his formative years. That doesn’t make it any less of a message worth reading.

Doland was like one great big family; lots of times troubles. But don't we have that in families? Sometimes bitter arguments, but we've had that in families. People are very different. But that's true in families. But there was a sense of being and a sense of belonging, and a sense of caring. Everybody knew everybody. There was really no place to hide. There was always a place to be. And you had the feeling that you were wanted.

It’s a beautiful story, one that allowed Humphrey, in that same speech, to challenge his audience to make their definition of community as broad and expansive as possible— to understand their responsibility to care not just for their immediate White neighbors, but for a nation of neighbors with lives very different than their own.

There are a lot of stories in Noem’s book that don’t resonate with me at all. That’s fine. They’re not for me. There was no way I was going to be compelled by her explanation for why her uber-lax Covid policy was not only correct but morally superior (she talks about freedom as a concept and leaves out the part about all the deaths), or why the Lakota Nation is to blame for not welcoming her as an ally (haters gonna hate, apparently), or even how her gender hasn’t affected her career (she noticed that “men seemed to be more ambitious than women” generally, but found that she could single-handedly solve that discrepancy by being more personally ambitious). The book’s extended climax— which explains how she first caught Trump’s attention— was lost on me, as a coastal (Lake Michigan) elitist who hates fun and freedom (if you’re curious, it goes like this: a whole bunch of Governors were pitching their biggest needs to Trump and he clearly wasn’t processing any of it, until Noem said “I want the fireworks back at Mount Rushmore,” and he was like, “Ooh, fireworks!").

The parts about Noem’s family farm worked, though. Even if I could fill in the missing subtext— about wealth unacknowledged and privilege unaccounted for— I still found myself compelled . Because even if her family did have all the advantages in the world, that didn’t make the drudgery of farm work easier or less lonely. There were still years that were too wet and years that were too dry. There was still the constant threat of the whole operation collapsing in on itself. There was still real, not just theoretical, hard work… every single day.

Most of all, though, there was the constant threat of tragedy. And I’m sure that Kristi Noem and her ghost writer knew what they were doing when they centered so much of the book on the single largest loss of her life thus far, but that didn’t make reading it any less emotionally wrenching. Noem’s father, Ron Arnold, really did die too young— not much older than I am now. He was killed in an absolutely horrific accident in a corn silo. Noem was in her early twenties and setting a course for her own life. I know that story well because it is literally my parents’ story, too— both of their Dads died in freak farm accidents, less than 45 minutes away from the Arnold family farm. My Mom and Dad were in their early twenties, too. Neither of their families had money to rebuild like Noem’s family did, so there's no Bucks family farm to go back to anymore. That doesn’t make their tragedy any less real, though, nor does it make any of their long days working their land any less tiring.

I read the story of Kristi Noem’s father’s death and yes, that felt like a point of connection. Yes, that felt like a thread between her life and mine. The problem is, Noem has chosen a path, one that is not much interested in ties that bind.

Kristi Noem may very well lose an election next week, but the story she tells about Eastern South Dakota has, of course, won the day. You won’t find nearly as many takers for “we’re all in this together” in contemporary South Dakota. You will, however, find plenty of believers in Noem’s pitch that every single one of us is the self-actualized hero of our own story.

Hubert Humphrey’s pitch was always a dreamy, utopian one— even during South Dakota’s more populist days. One of the stories he told most often was about his Dad trying to convince the rest of the town to form an electrical co-op instead of selling out to some slick, big city salesmen. Dad Humphrey lost that fight, and the citizens of Doland would eventually get fleeced. The big city guys took the money and ran, never having built the streetlights that they promised. In some ways, we communitarian dreamers have always been losing. But now, in the era of Trump and DeSantis and Noem, it can feel like the score against us has never been lopsided, especially in places like South Dakota pheasant country.

There are a lot of usual suspects for how we got here: It’s racism, of course, as well as conservative media and yell-y online conclaves and conspiracy theories and the nationalization of local politics and Citizens United. But as I read “Not My First Rodeo,” and found my scold-y mental ledger of Noem’s various omissions constantly running headfirst into real, relatable stories of long days and hard work, I thought about another reason why those of us who dream of justice and liberation keep losing: Our politics require people to see themselves not as heroes and rugged protagonists, but as parts of a larger whole— as neighbors whose lives and livelihoods are made possible by others and who therefore have a responsibility to others. That’s an intellectual jump. It’s fuzzy and hard to see. You don’t feel it every day, like the back ache that Noem’s father felt after years of farm work.

What isn’t an intellectual jump are all the ways that all of our lives— even those of us with the most structural advantages— truly are hard and tiring. Kristi Noem grew up in a fairly wealthy White family who were the beneficiaries of direct and indirect government largesse. That’s all true. AND it is also true that their farm required literal and actual back-breaking work, day in and day out, up to and including the day that their farm took her father’s life.

We’re never going to build a coalition that actually cares for one another if we allow Noem’s message to win– that simply because your life frequently feels hard, you are absolved from caring about anybody else. But so too do we lose if we don’t first give every single person in our communities— even the most privileged— the right to have their own stories matter.

As I was writing this piece, I received an absolutely lovely campaign email from Leah Spicer (who I highlighted in my piece on Sunday). Spicer is running for Wisconsin State Assembly from her boomerang hometown in the Eastern Driftless. It was the exact opposite of most political emails, in that it read like it was actually written by a human being. It was full of logistics about canvassing meetups in small towns and an upcoming thank you breakfast hosted by her parents. The best part, though, was when Spicer told her supporters that she very well might lose but that she still wanted us to know what she’s learned from knocking on her rural neighbors’ doors. It was the message that I needed, as I’ve been staring at a cursor far too late in the night, wondering how I can explain what I mean by a political invitation that acknowledges that everybody’s exhaustion matters without pandering to our lowest common denominator selfishness.

If you turn on the national news, you get the idea that we are horribly divided, and can’t agree about anything, but the good people of Wisconsin that I was lucky enough to talk to in person—from both sides of the political aisle—sounded remarkably similar when they talked about the things that mattered most to them.

They say they’re sick of politics, that they don’t trust either party. They say that their check was always small, and that inflation and corporate greed are making it even smaller. They worry about their kids—even if their kids are already adults. They worry about social security, and social media, about the climate, about the future of small farms. They worry about their underfunded schools, and about their diminishing personal liberties.

I learned that many people feel powerless and overwhelmed right now.

I’m not going to forget those conversations—whether I win or lose on Tuesday.

I read that and it made me proud of what Leah Spicer is going to build with her neighbors and excited for what I can build with my own and wistful for what I haven’t yet figured out how to build with the places my family has left behind.

The thing is, Kristi Noem is a lot like you, in that her life is easier than she sometimes lets on, but that doesn’t mean it hasn’t also been hard. But in a much more profound way, Kristi Noem is nothing like you. She’s selling the message that we’re all out for ourselves. She looks at the state that raised her and only sees a stepping stone. You know better though. You know that her home, and all of our homes, deserves far more than that.

End notes:

This week’s song of the week:

“Girl From The North Country” by Dear Nora (In honor of East River South Dakota, I went for this cover’s sparser arrangement over the Dylan/Cash original, even though that song too is perfect).

[As always, you can find the collected song of the week playlist on Apple Music or Spotify].

This week’s “White Pages Community Discussion for Paid Subscribers:”

We are talking about the Internet, and not about how it’s bad but about the little corners (either past or present) where it has been good for us. The vibes are good!

Also, you likely saw this, but I did my first-ever partially paywalled post on Sunday. It’s about Wisconsin. I’m still on the fence as to whether I’ll do it like that in the future or just send those bonus posts to subscribers’ only. I’m proud of the piece, though.

Oh, and of course: If any of this interests you but you don’t have the cash to subscribe, just email me (garrett@barnraisersproject.org).

She stole a tire iron out of another family’s trailer because her daughter’s gear was locked in theirs and she (the daughter) was late for competition. The elder Noem bloodied herself up pretty well, which was stressful because she had a gubernatorial debate that night. It is, in all fairness, a fairly decent story and if I too were a Presidential aspirant trying to present my rugged Western credentials I’d 100% put it in my book as well.